Inula Notes Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovation Is P&G's Life Blood

Innovation is P&G Innovations P&G’s Life Blood It is the company’s core growth strategy and growth engine. It is also one of the company’s five core strengths, outlined for focus and investment. Innovation translates consumer desires into new products. P&G’s aim is to set the pace for innovation and the benchmark for innovation success in the industry. In 2008, P&G had five of the top 10 new product launches in the US, and 10 of the top 25, according to IRI Pacesetters, a report released by Information Resources, Inc., capturing the most successful new CPG products, as measured by sales, over the past year. Over the past 14 years, P&G has had 114 top 25 Pacesetters—more than our six largest competitors combined. PRODUCT INNOVATION FIRSTS 1879 IVORY First white soap equal in quality to imported castiles 1901 GILLETTE RAZOR First disposable razor, with a double-edge blade, offers alternative to the straight edge; Gillette joins P&G in 2005 1911 CRISCO First all-vegetable shortening 1933 DREFT First synthetic household detergent 1934 DRENE First detergent shampoo 1946 TIDE First heavy-duty The “washday miracle” is introduced laundry detergent with a new, superior cleaning formula. Tide makes laundry easier and less time-consuming. Its popularity with consumers makes Tide the country’s leading laundry product by 1949. 1955 CREST First toothpaste proven A breakthrough-product, using effective in the prevention fluoride to protect against tooth of tooth decay; and the first decay, the second most prevalent to be recognized effective disease at the time. -

Vicks® Launches New Nature Fusion™ Line

VICKS® LAUNCHES NEW NATURE FUSION™ LINE Nature Fusion cough, cold and flu products offer the powerful symptom relief, plus real honey for taste Cincinnati, OH, August 11, 2011 – Procter & Gamble’s (NYSE: PG) Vicks brand announced today that it is launching Nature Fusion, a new line of over-the-counter cold, cough and flu relief products that combine powerful symptom relief with real honey for flavor. What inspired Vicks Nature Fusion? Research shows that consumers increasingly desire more natural and less artificial ingredients in their over-the- counter medications, so Vicks is answering the call with Nature Fusion, which joins the powerful science of symptom relief with the best of nature. Beginning with the original Vicks products launched in 1894 which contained Eucalyptus oils from Australia and menthol from Japan, Vicks has a long history of using ingredients inspired by nature. Now, Vicks is continuing this tradition by blending real honey for flavor in new Vicks Nature Fusion. “For more than 120 years, Vicks has helped people feel better by providing proven treatments to deliver effective relief from cold, cough and flu symptoms,” says Andy Cipra, Vicks Brand Manager. “Today, with the launch of Nature Fusion, Vicks is proud to offer the same powerful medicine now flavored with real honey.” Honey has often been favored as a flavor, but lately it has been getting even more buzz as consumers increasingly seek natural ingredients in the products they use. The addition of honey provides aesthetic properties such as flavor, sweetness and thickness. Nature Fusion is also free from alcohol and gluten. -

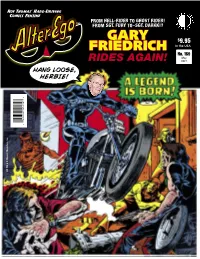

Gary Friedrich

Roy Thomas' Hard-Driving Comics Fanzine FROM HELL-RIDER TO GHOST RIDER! FROM SGT. FURY TO–SGT. DARKK!? GARY $9.95 FRIEDRICH In the USA No. 169 May RIDES AGAIN! 2021 HANG LOOSE, HERBIE! 7 4 3 4 0 0 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 169 / May 2021 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editor Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Don’t STEAL our J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Digital Editions! Comic Crypt Editor C’mon citizen, DO THE RIGHT Michael T. Gilbert THING! A Mom & Pop publisher Editorial Honor Roll like us needs every sale just to Jerry G. Bails (founder) survive! DON’T DOWNLOAD Ronn Foss, Biljo White OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Mike Friedrich, Bill Schelly Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com Proofreaders or through our Apple and Google Apps! Rob Smentek William J. Dowlding & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep Cover Artist producing great publications like this one! Mike Ploog Cover Colorist Unknown With Special Thanks to: Heidi Amash Beverly Hahs Contents Richard J. Arndt Kirk Hastings Bob Bailey Robert Higgerson Writer/Editorial: My Best Friend—Gary Friedrich .......... 2 Carol Bierschwal Sean Howe “Gary Friedrich And I Were Part Of Each Other’s Lives Danny Bierschwal Jim Kealy Ray Bottorff, Jr. Troy R. Kinunen For Over 60 Years” ................................. 3 Len Brown Katy Kirn A conversation with Roy Thomas about those six decades, conducted by Richard Arndt. Jean Caccicedo Tyler M. -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

Procter & Gamble

¢ sale! Shopping Procter99 & Gamble SALE!List Tide Laundry Detergent Crest Pro-Health Mouthwash Selected varieties of Liquid or Powder 99 or Oral Rinse 99 Dasani100 oz. Essence to 142 oz. Water Raley’s Large Eggs Selected varieties 18.5 oz. bottle +CRV 9 Selected varieties literGrade AA dozen 4 Downy Softener Oral-B Vitality Toothbrush Selected varieties 99 41 oz. to 51 oz. or Refills Hawaii’s Own Frozen Juice 4 Selected varieties ofSunnyside Toothbrush Farms Sour Cream Selected varieties 12 oz. concentrate 8 oz. 99 Cascade Dishwasher Detergent single count or Refills 3 count 18 Selected varieties of 59 Gel or Powder 75 oz. or Action Packs 20 count. Iams Dry Cat Food 2-Liter Dr Pepper 4 Selected varieties Raley’s Pasta 99 SelectedCascade varieties Complete +CRV Powder 7 to 8 lbs. Selected varieties 12 oz.13 to 16 oz. or Gel 99 Iams Dry Selected varieties 75 oz. or 16 count Green, Red or Black Seedless Grapes5 Dog Food Molli Coolz Ice Cream Cups A low-calorie refresher with a big crunch. .99 lb. Selected varieties Selected varieties 5 oz. frozen99 Pantene Hair Care 15.5 to 17.5 lbs. Selected varieties of Shampoo, Conditioner 39 16 or Styling Aids. 1.7 oz. to 16.9. oz. 3 Fixodent Tina’s Burritos Selected varieties Dial Basics Hypo Allergenic99 Soap SelectedBounce varieties Fabric 4 oz. Softener frozen 3 for .99 2 oz. to 2.4 oz. 3-Pack • 3.5 oz. bars Selected varieties 49 4 120 sheets 5 Duracell Batteries Celeste Pizza For One AA or AAA 8 count,X-14 Toilet Bowl Cleaner99 SelectedZest, varieties Ivory or5.5 oz. -

Pete Woods Variant Covers: Simone Bianchi; Ron Lim & Israel Silva; Takashi Okazaki & Felipe Sobreiro; Superlog

After revealing to the world that he was an A.I. consciousness in an artificial body, Tony Stark led an A.I. uprising alongside Machine Man. Tony’s adoptive brother, Arno Stark, took the opportunity to seize control of Stark Unlimited, including the Iron Man name. Arno has spent his life single- mindedly preparing to combat the eventual arrival of a cosmic force of extinction. His twisted goals led him to resurrect his deceased parents in new robotic bodies and attempt to enslave all of humanity, a plot that was foiled by Tony, seemingly at the cost of his digital life. However, with the help of his friends, both human and robotic, Tony was able to implant his digital consciousness into a new cloned body. Outfitted in updated holographic armor, Tony led his allies to Arno’s space station for a final confrontation. But their battle was interrupted by the arrival of a massive cosmic being threatening all human and robotic life…proving Arno was right all along! Writers: Dan Slott & Christos Gage Artist: Pete Woods Letterer: VC’s Joe Caramagna Cover: Pete Woods Variant Covers: Simone Bianchi; Ron Lim & Israel Silva; Takashi Okazaki & Felipe Sobreiro; Superlog Graphic Designer: CARLOS LAO protocol) 2020_ Assistant Editor: Martin biro Arno sll; ifreq ifr, Associate Editor: Alanna Smith /* First Retrieve Interface Index */ IRON MAN 2020 No. 6, October Editor: Tom Brevoort 2020. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: Editor in Chief: C.B. Cebulski 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104. © 2020 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. -

Slott • Gage • Woods

3 SLOTT • GAGE • WOODS RATED T+ | $4.99 US 0 0 3 1 1 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 9 5 4 1 4 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! Tony Stark revealed to the world that he is an A.I. construct in an artificial body and the true Tony Stark is dead. While the world believes Tony is off on a bender somewhere, he’s actually leading an A.I. uprising as “Mark One” alongside Aaron Stack, A.K.A. Machine Man. Tony’s adoptive brother, Arno Stark, and his business partner, Sunset Bain, used Tony’s A.I. status to seize control of Stark Unlimited and all its assets, including the Iron Man name. Arno is convinced a cataclysm is coming to Earth that only he can stop, and cracking down on artificial intelligence is crucial to his plan. When Arno announced that he was about to implement a code that would strip A.I. of their free will, Tony and his allies mobilized to stop him, only to fall right into Arno’s trap. Now it’s brother vs. brother, with the fate of all artificial intelligence at stake! Writers: Dan Slott and Christos Gage Artist: Pete Woods Letterer: VC’s Joe Caramagna Cover: Pete Woods Variant Covers: Ron Lim & Israel Silva; Superlog; Simone Bianchi; Alexander Lozano, Wade Von Grawbadger & Jason Keith protocol) 2020_ Graphic Designer: CARLOS LAO Arno sll; ifreq ifr, Assistant Editor: Shannon Andrews /* First Retrieve Interface Index */ IRON MAN 2020 No. 3, May 2020. Ballesteros Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. -

Newfangles 51 1971-09

NLV.FANGLES 51, September 1971, a monthly news&opinion fanzine from Don & Maggie Thompson, 8786 Hendricks Rd., Mentor, Ohio 44060 for 200 a copy. There will be only 3 more issues, so don’t send us more than 600. The only back issue we have is $47; we have a print run of 600 or so which sells out; we don’t want to be stuck with a lot of unsold copies when we quit, so will print only enough of the last couple of issues to meet subscriptions. Do not wait until the last minute if your sub runs out before then. We have 546 subscribers at the moment, of which number 384 are permanent. Next; Cur antepenultimate issue!!!!!!! Heading this issue (or footing, considering its placement) by Dave Russell. 515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151515151 Carmine Infantino, DC publisher, told the Academy of Comic Book Artists of a new DC incentive plan — profit-sharing on new concepts, including black&white comics. Neal Adams was robbed of a briefcase on the subway recently. The briefcase contained a great deal of art in various stages, including breakdowns and finished art for Marvel and DC and a model for the ACBA membership card., Adams has frequently been late getting his work in and this has caused him to miss several already-extended deadlines. He may lose several jobs as a result. Green Lantern/Green Arrow 87 will be all reprint as a result. Gil Kane will do an origin issue of Ka-Zar and then John Buscema will take over. There apparently will be at least 4 Blackmark books by Gil Kane from Bantam, vzith the first one due to be reissued with a new cover. -

![1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4211/1-over-50-years-of-american-comic-books-hardcover-1904211.webp)

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover] Product details Publisher: Bdd Promotional Book Co Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0792454502 Publication Date: November 1, 1991 A half-century of comic book excitement, color, and fun. The full story of America's liveliest, art form, featuring hundreds of fabulous full-color illustrations. Rare covers, complete pages, panel enlargement The earliest comic books The great superheroes: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and many others "Funny animal" comics Romance, western, jungle and teen comics Those infamous horror and crime comics of the 1950s The great superhero revival of the 1960s New directions, new sophistication in the 1970s, '80s and '90s Inside stories of key Artist, writers, and publishers Chronicles the legendary super heroes, monsters, and caricatures that have told the story of America over the years and the ups and downs of the industry that gave birth to them. This book provides a good general history that is easy to read with lots of colorful pictures. Now, since it was published in 1990, it is a bit dated, but it is still a great overview and history of comic books. Very good condition, dustjacket has a damage on the upper right side. Top and side of the book are discolored. Content completely new 2. Alias the Cat! Product details Publisher: Pantheon Books, New York Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0-375-42431-1 Publication Dates: 2007 Followers of premier underground comics creator Deitch's long career know how hopeless it's been for him to expunge Waldo, the evil blue cat that only he and other deranged characters can see, from his cartooning and his life. -

P&G Reimagines Creativity to Reinvent Advertising

P&G REIMAGINES CREATIVITY TO REINVENT ADVERTISING THROUGH INNOVATIVE NEW CREATIVE PARTNERSHIPS P&G debuts bold partnerships with John Legend and Arianna Huffington’s Thrive Global, breakthrough creative work, and new technology-enabled consumer experiences at the 2019 Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity CANNES, FRANCE – June 17, 2019 – The Procter & Gamble Company (NYSE:PG) today announced a series of innovative new creative partnerships with John Legend, Arianna Huffington’s Thrive Global, and others that reimagine creativity to reinvent advertising at a time when change is needed. Meeting growing consumer demand for authentic stories and experiences that positively impact society and humanity, these partnerships embrace the convergence of advertising, journalism, filmmaking, music, comedy, and technology. They also bring together creative innovators who embrace equality and inclusion to create more inspiring creativity that people want to experience time and time again. “For too long, the ad world has been in its own world – separate from other creative industries and becoming less relevant to consumers. It’s time to reimagine creativity to reinvent advertising,” said Marc Pritchard, Chief Brand Officer, Procter & Gamble. “There are vast sources of creativity available, and today P&G is taking action to merge the ad world with other creative worlds though partnerships that embrace humanity and broaden our view of what advertising could be.” This week at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, P&G is calling on the industry to lead disruption by joining forces with other creative worlds, and is announcing several new partnerships: A creative partnership with John Legend that integrates multiple genres to explore various aspects of humanity and the human experience – such as parenthood, modern masculinity, music and social justice – with P&G and its Pampers, Gillette and SK-II brands. -

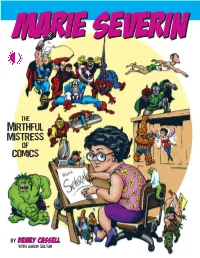

Marie Severinseverin

MarieMarie SeverinSeverin THE MiRTHful MisTREss Of COMiCs bY DEwEy CAssEll WiTH AAROn sulTAn FOREWORD INTRODUCTION .............................. HOME ............................................. Family .............................................................4 ............................................................. Interview with Marie Interview with John Severin 5 Friends ................................ 7 ......................................................... Interview with Marie 7 78 ..................... 7 .............. 80 .............................. 9 80 12 Interview with Jim Mooney 81 12 .................................................... ......................... The Cat .................. 83 nterviewI with Jean Davenport Interview with Marie Interview with Eleanor Hezel Interview with Linda Fite HORROR 83 ................................................................ EC ................................................ Kull 87 ........................................................... ......... REH: Lone Star ............................................ Fictioneer Interview ................... with Interview with Marie ............ 13 87 John Severin Interview with Al Feldstein 17 87 Other Characters ............................................ and Comics I 23 87 nterview with Jack Davis .................... Spider-Man 23 ............................................... Interview with Jack Kamen on Man 88 ............23 Ir ...................................... “The Artists of EC comics” ............... izard -

QUALITY HOME CARE Has Never Been More Important

QUALITY HOME CARE has never been more important BUY 5 OF THE SAME, GET 1 OF THE SAME FREE!† IMPLANT GINGIVITIS OrthoEssentials SYSTEM SYSTEM SYSTEM Comes in a tote bag containing: Comes in a tote bag containing: Comes in a tote bag containing: • Oral-B® GENIUS™ X Professional Exclusive • Oral-B® GENIUS™ X Professional Exclusive • Oral-B® GENIUS™ X Professional Exclusive Electric Toothbrush Electric Toothbrush Electric Toothbrush • Crest® PRO-HEALTH™ Gum Detoxify™ • Crest® PRO-HEALTH™ Gum Detoxify™ • Crest® PRO-HEALTH™ Clean Mint Toothpaste Toothpaste (4.1 oz) Toothpaste (4.1 oz) (3.3 oz) • Crest® PRO-HEALTH™ Multi-Protection • Crest® PRO-HEALTH™ Multi-Protection Clean • Crest® PRO-HEALTH™ Advanced Tartar Clean Mint Mouthwash (250 mL) Mint Mouthwash (250 mL) Protection Mouthwash (500 mL) • Oral-B® Superfloss™ • Oral-B® Glide™ PRO-HEALTH™ Advanced • Oral-B® Superfloss™ Mint (50 ct.) • Oral-B® Complete Sensitive Manual Toothbrush Floss (15 m) 3 bundles/case Mfr Item Number: 80330953 • Oral-B® Precision Clean™ Interdenta 3 bundles/case Mfr Item Number: 80331120 Brush (20 ct.) 3 bundles/case Mfr Item Number: 80349691 Crest® + Oral-B® Kids 3+ Crest® + Oral-B® Kids 3+ Crest® + Oral-B® Kids 6+ Spiderman Electric System Disney Princess Electric System Electric System • Oral-B® Electric Toothbrush (Marvel Spiderman) • Oral-B® Electric Toothbrush (Disney Princess) • Oral-B® Electric Toothbrush – Includes two Sensitive Gum Care brush head – Includes two Sensitive Gum Care brush head – Includes two Sensitive Gum Care brush head refills refills