The Case Study of Michael Jordan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Cartwright

Bill Cartwright Bill Cartwright is a winner! He was in his basketball career, he is in his business career and he continues to be a winner in his family life. Cartwright was a 7’1” NBA center was a dominant physical presence for 3 teams. He was drafted in the 1st round of the 1979 NBA draft, #3 overall, by the New York Knicks. He made an All-Star Game appearance in his rookie season and was named to the All Rookie First Team. He was named team captain of the Knicks but 4 separate fractures to his foot began to slow him steps. Bill was traded to the Chicago Bulls in 1988 and it was here that he fully established himself as a presence. He was once again named team captain and led the Bulls to 3 consecutive NBA championships in 1991, 1992, and 1993. In 1994, he moved on as a free agent to the Seattle SuperSonics where he spent the final season of his 16 year playing career. In 1996, Bill rejoined the Chicago Bulls as an assistant coach and won two more NBA championships with the team in 1997 and 1998. In 2001, he took over the Bulls’ head coach where he remained until 2003, coaching a team that had been stripped of its best players. He moved on from Chicago to be an assistant coach with the New Jersey Nets and Phoenix Suns before spending the 2013 season coaching in Japan and 2014 as head coach of the Mexican National Team. Cartwright has firmly established himself in the business world as the owner of a car dealership and a restaurant and he recently divested himself from a successful security services firm. -

How David Kelly of the Golden State Warriors Serves the Winning Team

Order in the Court: How David Kelly of the Golden State Warriors Serves the Winning Team Skills and Professional Development 1 / 7 As the general counsel of the Golden State Warriors, one of the NBA's best basketball teams, David Kelly lives the life of at least five different general counsel. He serves as a basketball lawyer, startup lawyer, consumer lawyer, real estate lawyer, and media lawyer. That is how the humble and multitalented Kelly oversees the legal needs of Golden State Warriors, an organization that is constantly in the public eye. Just like his team, he brings a focus on excellence and an easy grace, no matter what each day brings him. GC of a basketball team: When Joe Lacob and Peter Guber started looking for a general counsel in 2012 for the team they purchased at the end of 2010, David Kelly jumped at the opportunity. He had just made partner at Katten Muchin Rosenman, a well known Chicago sports and entertainment law firm, and he had done corporate work for various sports teams, including working as outside counsel for Lacob on Guber on their purchase of the team. Kelly explained, "I have always had a passion for the sports and entertainment industries and I had my eye on going in-house in one industry or the other. When I heard Lacob and Guber were going to hire a GC, I knew it would be my dream job. The Warriors were struggling as a franchise at the time, but I knew Lacob and Guber had the tools and a plan – and Stephen Curry – and would turn things around. -

How the Golden State Warriors Have Hyper-Commercialized Professional Sports

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2019 A “Steph” in The Process: How The Golden State Warriors Have Hyper-Commercialized Professional Sports Danielle Arena Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Arena, Danielle, "A “Steph” in The Process: How The Golden State Warriors Have Hyper- Commercialized Professional Sports" (2019). Senior Theses. 119. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arena 1 Dominican University of California A “Steph” in The Process: How The Golden State Warriors Have Hyper-Commercialized Professional Sports A Senior Capstone Submitted to The Faculty of the Division of Public Affairs In Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History Department of History By Danielle Arena Arena 2 Abstract This research aims to highlight the significant impact the Golden State Warriors have had on the commercialization of sports. This is especially relevant and corresponds to the Warriors back-to-back championships and their rise from an overlooked team to one of the most popular teams in the National Basketball League (NBA). According to Forbes, the Warriors have gone from NBA obscurity to the third most valuable team in the NBA. The objective of this research is to prove the importance of both physical prowess and business savvy in the sports world to become truly successful as a professional franchise. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS PLAYERS IN POWER: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF CONTRACTUALLY BARGAINED AGREEMENTS IN THE NBA INTO THE MODERN AGE AND THEIR LIMITATIONS ERIC PHYTHYON SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Political Science and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Labor and Employment Relations Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Boland J.D, Adjunct Faculty Labor & Employment Relations, Penn State Law Thesis Advisor Jean Marie Philips Professor of Human Resources Management, Labor and Employment Relations Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. ii ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the current bargaining situation between the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the changes that have occurred in their bargaining relationship over previous contractually bargained agreements, with specific attention paid to historically significant court cases that molded the league to its current form. The ultimate decision maker for the NBA is the Commissioner, Adam Silver, whose job is to represent the interests of the league and more specifically the team owners, while the ultimate decision maker for the players at the bargaining table is the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), currently led by Michele Roberts. In the current system of negotiations, the NBA and the NBPA meet to negotiate and make changes to their collective bargaining agreement as it comes close to expiration. This paper will examine the 1976 ABA- NBA merger, and the resulting impact that the joining of these two leagues has had. This paper will utilize language from the current collective bargaining agreement, as well as language from previous iterations agreed upon by both the NBA and NBPA, as well information from other professional sports leagues agreements and accounts from relevant parties involved. -

Comprehension Builders Research Reveals That the Single Most Valuable Activity for Developing Students’ Com- Prehension Is Reading Itself

Daily Comprehension Builders Research reveals that the single most valuable activity for developing students’ com- prehension is reading itself. At its core, comprehension is an active process in which students think about text and gain meaning from it. In order for them to build compe- tence in comprehension, their reading should be purposeful and reflective. It should foster the exploration of genre, language, and information. Daily Comprehension Build- ers is a resource that provides the instructional framework to help your students build strength in comprehension and achieve success in reading! Comprehension Basics Comprehension begins with what a student knows about a topic. It builds as a child reads and actively makes connections between new information and prior knowledge. Understanding is increased as the student organizes what he has read in relationship to what he already knows. To successfully comprehend, students need to master a variety of critical skills, such as constructing word meanings from context, determin- ing main ideas and locating details to support them, sequencing, inferring and drawing conclusions, making generalizations, predicting, summarizing, and sensing an author’s purpose. Daily Comprehension Builders provides multiple opportunities for reinforcing these essential skills, resulting in increased learning and competence in reading. About This Book Thirty-six high-interest reading selections, each accompanied by five activities and two to three reproducible skill sheets, are featured in this book. (See the unit features detailed below.) Each unit is clearly organized and highlights one of the following topics or genres: sports, famous people, animals, oddities, real-life mysteries, and adventure. Use each unit in its entirety, or pick and choose activities to build specific skills. -

2000 NBA ALL-STAR TECHNOLOGY SUMMIT the Future of Sports Programming the Ritz-Carlton, San Francisco

2000 NBA ALL-STAR TECHNOLOGY SUMMIT The Future of Sports Programming The Ritz-Carlton, San Francisco FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 11 8:15 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. Continental Breakfast – The Ritz Carlton Ballroom 9:00 a.m. – 9:15 a.m. Welcome Ahmad Rashad, Summit Host Opening Comments David Stern, NBA Commissioner 9:15 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. Panel I: Brand, Content and Community Moderator: Tim Russert (Moderator, Anchor, NBC News) Panelists Leonard Armato (Chairman & CEO, Management Plus Enterprises/DUNK.net) Geraldine Laybourne (Chairman, CEO & Founder, Oxygen Media) Rebecca Lobo (Center/Forward, New York Liberty) Kevin O’Malley (Senior Vice President, Programming, Turner Sports) Al Ramadan (CEO, Quokka Sports) Isiah Thomas (Chairman & CEO, CBA) Description Building a successful brand is at the core of establishing a community of loyal consumers. What types of companies and brands are best positioned for long-term success on the Net? Do new Internet-specific brands have an advantage over established off-line brands staking their claims in cyberspace? Or does the proliferation of Web-specific properties give an edge to established brands that the consumer knows, understands and is comfortable with? Panelists debate the value of an off-line brand in building traffic and equity on-line. 10:15 a.m. – 10:30 a.m. Break 10:30 a.m – 11:30 a.m Panel II: The Viewer Experience: 2002, 2005 and Beyond Moderator: Bob Costas (Broadcaster, NBC Sports) Panelists George Blumenthal (Chairman, NTL) Dick Ebersol (Chairman, NBC Sports and Olympics) David Hill (Chairman & CEO, FOX Sports Television Group) Mark Lazarus (President, Turner Sports) Geoff Reiss (SVP of Production & Programming, ESPN Internet Ventures) Bill Squadron (CEO, Sportvision) Description Analysts predict that sports and entertainment programming will benefit most from the advent of large pipe broadband distribution. -

First in Thirst

Concentrated Knowledge™ for the Busy Executive • www.summary.com Vol. 28, No. 1 (3 parts), Part 2, January 2006 • Order # 28-02 FILE: MARKETING ® How Gatorade Turned the Science of Sweat Into a Cultural Phenomenon FIRST IN THIRST THE SUMMARY IN BRIEF When was the last time you watched or took part in a sporting event By Darren Rovell where there were no sports drinks? And although there are other sports drinks out there, how often do you see a brand other than Gatorade? Gatorade invented the sports drink 40 years ago, and it has been first in CONTENTS the marketplace — by a long shot — ever since. But Gatorade is more than just a thirst quencher and a dominant brand. It has become an icon of pop- Sweat in a Bottle ular culture — witness the globally televised “Gatorade baths” adminis- Pages 2, 3 tered to victorious football coaches — and a must-have symbol of “hip” The Mystique Is Born well beyond the athlete’s realm. Pages 3, 4 Published to coincide with the 40th anniversary of Gatorade’s invention, From Field to Shelves First in Thirst chronicles the rise of the sports-drink industry and the near- Pages 4, 5 monopoly that Gatorade has built and maintained through savvy marketing and branding strategies. In this summary, business journalist Darren Rovell Those Famous Green Cups offers an inside look at the negotiations, battles, lawsuits, mergers and acqui- Page 5 sitions, product strategies, lucky breaks, and even the missteps that have Wrestling Over Gatorade attended Gatorade’s reign as the 800-pound gorilla of the sports-drink scene. -

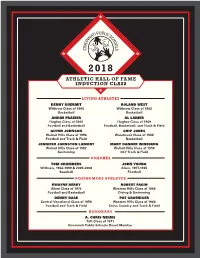

Class of 2018

2018 ATHLETIC Hall OF FaME INDUCTION ClaSS LIVING ATHLETES DENNY DUERMIT ROLAND WEST Withrow Class of 1969 Withrow Class of 1962 Basketball Basketball ANDRE FRAZIER AL LaNIER Hughes Class of 2000 Hughes Class of 1969 Football and Basketball Football, Basketball, and Track & Field GLYNN JOHNSON CHIP JONES Walnut Hills Class of 1996 Woodward Class of 1988 Football and Track & Field Basketball JENNIFER JOHNSTON LaMONT MaRY DANNER WINEBERG Walnut Hills Class of 1982 Walnut Hills Class of 1998 Swimming OLY Track & Field COACHES TOM CHAMBERS JOHN YOUNG Withrow, 1966-1999 & 2005-2008 Aiken, 1977-1985 Baseball Football POSTHUMOUS ATHLETES DwaYNE BERRY ROBERT FagIN Aiken Class of 1975 Western Hills Class of 1946 Football and Basketball Diving & Swimming DENNY DASE PaT GROENIGER Central Vocational Class of 1959 Western Hills Class of 1946 Football and Track & Field Cross Country and Track & Field HONORARY A. CHRIS NELMS Taft Class of 1971 Cincinnati Public Schools Board Member WELCOME TO THE 2018 CPS ATHLETIC HALL OF FAME INDUCTION CEREMONY HOSTED BY PRESENTED BY THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 2018 SOCIal HOUR: 5PM | WELCOME AND DINNER: 6PM INDUCTION CEREMONY: 7PM MASTERS OF CEREMONY John Popovich, Sports Director WCPO Channel 9 Lincoln Ware, SOUL 101.5 COAch INDucTEES Tom Chambers, Withrow High School John Young, Aiken High School POSThumOUS INDucTEES Dwayne Berry, Aiken High School Denny Dase, Central Vocational High School Robert Fagin, Western Hills High School Pat Groeniger, Western Hills High School Livi2018NG AThlETE INDucTEES Denny Duermit, Withrow High School Andre Frazier, Hughes High School Glynn Johnson, Walnut Hills High School Jennifer Johnston LaMont, Walnut Hills High School Roland West, Withrow High School Chip Jones, Woodward High School Al Lanier, Hughes High School Mary Danner Wineberg, Walnut Hills High School HONORARY INDucTEE A. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 06/07/19 Arizona Coyotes Boston Bruins cont'd 1146137 Arizona Coyotes sign defenseman Robbie Russo to 1146177 Watch Bruins fans give injured Zdeno Chara huge ovation 1-year deal before Game 5 vs. Blues 1146138 It’s safe to say that some of us are a little nuts’: Chara’s 1146178 Watch Bobby Orr, Derek Sanderson serve as Bruins' decision may add to NHL’s playoff lore Stanley Cup Game 5 banner captains 1146179 Bruins' Zdeno Chara (jaw) medically cleared to play in Boston Bruins Game 5 1146139 Painful night all around for Zdeno Chara and Bruins 1146180 Bruins' awesome Stanley Cup Game 5 hype video 1146140 Late non-call stole the show in Bruins’ Game 5 loss features Tom Brady cameo 1146141 Tyler Bozak’s apparent slew foot of Noel Acciari in Game 1146181 Bruins vs. Blues live stream: Watch 2019 Stanley Cup 5 ‘was a missed call on the biggest stage of hockey’ Final Game 5 online 1146142 Series deficit about more than officials, but Game 5 was a 1146182 Who could Bruins banner captains be for Games 5 and 7 crime of the Stanley Cup Final? 1146143 Blues beat Bruins to take 3-2 lead in Stanley Cup Final 1146183 Bruins' scoreless second line has to 'have more of an 1146144 Non-call on third-period trip hard to ignore after 2-1 loss attack mentality' 1146145 Zdeno Chara joins a stellar list of those who played in pain 1146184 ‘It’s safe to say that some of us are a little nuts’: Chara’s 1146146 Bruins’ Matt Grzelcyk out for Game 5 of Stanley Cup Final decision may add to NHL’s playoff lore 1146147 NBC’s Patrick Sharp knows -

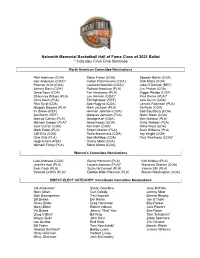

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

The Olympics Are As Much an Exercise in Patriotism As They Are An

OLYMPICS | LONDON 2012 America's Best Moments he Olympics are as much an exercise in patriotism as they Tare an individual achievement. It just feels good to root for athletes from your own country. The United States is fortunate to have some of the most thrilling victories in the THE DREAM TEAM history of summer Olympics. Here's a look Widely considered the at a few of them. most talented Olympic team to compete in any sport, the 1992 United States men's JESSE OWENS Olympic basketball team Adolf Hitler had plans to make the 1936 consisted of the biggest Olympic games a demonstration of the stars in the National superiority of the Aryan race. Basketball Association. Jesse Owens had other ideas. Consisting entirely of bas- Owens, a black man from America, won ketball icons — including four different gold medals in Berlin in one Michael Jordan, David of history's greatest athletic accomplish- Robinson, Patrick Ewing, ments. It would take nearly 50 years — Larry Bird, Scottie until the 1984 games — before any runner Pippen, Clyde Drexler, equaled his Olympic four-gold-medal per- Karl Malone, Charles formance. Barkley and Magic Hitler is said to have been embarrassed Johnson — the Dream that a non-German could dominate the Team soundly defeated Berlin games so completely. Owens showed every opponent in the that it's talent and training, not a particular games. set of genetics, that leads to victory. They beat their com- petition by an average of 43 points per game, MARY LOU RETTON making it look easy to In 1984, when the Cold War was still sim- win a gold medal. -

Fairleigh Dickinson Men's Basketball Team Dropped Its First Scoring Margin 4.7 11.3 Nov

FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON MEN’S BASKETBALL 2016 NEC CHAMPIONS NCAA Tournament Appearances Game 4: 1985, 1988, 1998, 2005, 2016 Fairleigh Dickinson (1-2) NEC Champions vs Lipscomb (2-2) 1985, 1988, 1998, 2005, 2016 Saturday, Nov. 19 - 5:30 p.m. - Rose Hill Gymnasium - Bronx, N.Y. NEC Regular Season Champions 1982, 1986, 1988, 1991, 2006 LIVE COVERAGE: Audio: Sam Levitt (KnightVision) Stats: sidearmstats.com/fordham/mbball FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON VS. LIPSCOMB ALL-TIME SERIES Tonight's Tale of the Tape... • Tonight is the first ever meeting between the Knights and Bisons FDU Lip Overall 1-1 1-1 2016-17 Men’s Basketball KenPom.com 271 252 Schedule/Results FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON LAST TIME OUT Scoring Offense 73.7 86.8 Scoring Defense 69.0 75.5 November • The Fairleigh Dickinson men's basketball team dropped its first Scoring Margin 4.7 11.3 Nov. 11 at Seton Hall L, 70-91 of three games at the Johnny Bach Classic, falling to the host FG% 44.6 50.4 Nov. 15 FDU-FLORHAM W, 96-48 Fordham Rams 68-55 on Friday night. 3-Pt. FG% 33.3 37.9 • The Knights shot a higher overall percentage from the field than FT% 67.7 68.3 Nov. 18 at Fordham L, 55-68 the Rams, 39.1 percent (18-of-46) to 36.5 (19-of-52) percent FG% Defense 42.4 42.3 Nov. 19 Lipscomb (at Fordham) 5:30 PM but struggled mightily from downtown, converting just 3-of-16 3-Pt. FG% Defense 33.9 32.9 Nov. 20 Saint Peter’s (at Fordham) 1 PM (18.8%) from behind the arc.