Grant Farred Entre Nous Grant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Semanal FILBA

Ya no (Dir. María Angélica Gil). 20 h proyecto En el camino de los perros AGENDA Cortometraje de ficción inspirado en PRESENTACIÓN: Libro El corazón y a la movida de los slam de poesía el clásico poema de Idea Vilariño. disuelto de la selva, de Teresa Amy. oral, proponen la generación de ABRIL, 26 AL 29 Idea (Dir. Mario Jacob). Documental Editorial Lisboa. climas sonoros hipnóticos y una testimonial sobre Idea Vilariño, Uno de los secretos mejor propuesta escénica andrógina. realizado en base a entrevistas guardados de la poesía uruguaya. realizadas con la poeta por los Reconocida por Marosa Di Giorgio, POÉTICAS investigadores Rosario Peyrou y Roberto Appratto y Alfredo Fressia ACTIVIDADES ESPECIALES Pablo Rocca. como una voz polifónica y personal, MONTEVIDEANAS fue también traductora de poetas EN SALA DOMINGO FAUSTINO 18 h checos y eslavos. Editorial Lisboa SARMIENTO ZURCIDORA: Recital de la presenta en el stand Montevideo de JUEVES 26 cantautora Papina de Palma. la FIL 2018 el poemario póstumo de 17 a 18:30 h APERTURA Integrante del grupo Coralinas, Teresa Amy (1950-2017), El corazón CONFERENCIA: Marosa di Giorgio publicó en 2016 su primer álbum disuelto de la selva. Participan Isabel e Idea Vilariño: Dos poéticas en solista Instantes decisivos (Bizarro de la Fuente y Melba Guariglia. pugna. 18 h Records). El disco fue grabado entre Revisión sobre ambas poetas iNAUGURACIÓN DE LA 44ª FERIA Montevideo y Buenos Aires con 21 h montevideanas, a través de material INTERNACIONAL DEL producción artística de Juanito LECTURA: Cinco poetas. Cinco fotográfico de archivo. LIBRO DE BUENOS AIRES El Cantor. escrituras diferentes. -

CEO Succession Planning and Leadership Development- Corporate Lessons from FC Barcelona

International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research (IJMSR) Volume 1, Issue 2 (July 2013), PP 45-49 www.arcjournals.org CEO Succession Planning and Leadership Development- Corporate Lessons from FC Barcelona Amanpreet Singh Chopra Phd. Research Scholar, UPES, India Abstract: Author studied the development program(s) and leadership succession planning strategies of FC Barcelona, one the most successful club in Spanish Football history and analyzed that success of club is deeply rooted in its strategies from grooming of homegrown talent at La Masia to the appointment of coaching staff. Taking cue from club strategies author identified 5 lessons for Corporate- Developing organizational belief in growth strategies, Developing young executive through structured T&D programs, Present career progression opportunities to young employees, Develop „inward‟ succession planning framework through grooming in-house talent and above all nurturing the philosophy of “Más que una empresa”(More than a company). Key Words: Succession Planning, Leadership Development, Sports Psychology 1. FC BARCELONA Futbol Club Barcelona also known as FC Barcelona and familiarly as Barça, is a professional football club, based in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Founded in 1899 by a group of Swiss, English and Catalan footballers led by Joan Gamper, the club has become a symbol of Catalan culture and Catalanism, hence the motto "Més que un club" (More than a club). It is the world's second-richest football club in terms of revenue, with an annual turnover of €398 million (2011). The unique feature of the club is that unlike many other football clubs, the supporters own and operate Barcelona. Jack Greenwell was the first fulltime club manager from 1917 to 1924 under which club grabbed 6 tournament honors. -

LEARNING from the BEST Gabriel Masfurroll

LEARNING FROM THE BEST Gabriel Masfurroll Foreword I first met Gabriel Masfurroll in the seventies, when he was a teenager and a competitive swimmer. At that time, swimming played a very important part in my life because the European Championships held in Barcelona in 1970, in which I participated actively, were an excellent yardstick for the Olympic Games of 1992. Masfurroll was living in the Residencia Joaquín Blume in Barcelona, run by my friend Ricardo Sánchez, and we had good friends in common such as Santiago Esteva and Maria Paz Corominas, swimmers who in their day were key figures in Spanish sport. I shall never forget something ‘Gaby’, as his friends call him, said to me when he was still very young: “Mr. Samaranch, when I grow up I want to be like you and match your achievements. I also love sport and believe I can do a lot for it”. It comes as no surprise to me, then, to see Masfurroll holding positions of responsibility in leading sporting institutions. A few years later, I met up with “Gaby” again when he was head of the Quirón Clinic in Barcelona. Since then we have kept in touch on a regular basis. We have met and written to each other on numerous occasions and I recall a beautiful picture, on display at the headquarters of the Olympic Committee in Lausanne, which he gave me on one of his visits. I have followed his career very closely over these years and that phrase “when I grow up I want to be like you”, made me take a keen interest in both his personal and professional development. -

Fis Hm an Pele, Lio Nel Messi, and More

FISHMAN PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE JON M. FISHMAN Lerner Publications Minneapolis SCORE BIG with sports fans, reluctant readers, and report writers! Lerner Sports is a database of high-interest LERNER SPORTS FEATURES: biographies profiling notable sports superstars. Keyword search Packed with fascinating facts, these bios Topic navigation menus explore the backgrounds, career-defining Fast facts moments, and everyday lives of popular Related bio suggestions to encourage more reading athletes. Lerner Sports is perfect for young Admin view of reader statistics readers developing research skills or looking Fresh content updated regularly for exciting sports content. and more! Visit LernerSports.com for a free trial! MK966-0818 (Lerner Sports Ad).indd 1 11/27/18 1:32 PM Copyright © 2020 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Lerner Publications Company A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Main body text set in Aptifer Sans LT Pro. Typeface provided by Linotype AG. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Fishman, Jon M., author. Title: Soccer’s G.O.A.T. : Pele, Lionel Messi, and more / Jon M. -

Who Can Replace Xavi? a Passing Motif Analysis of Football Players

Who can replace Xavi? A passing motif analysis of football players. Javier Lopez´ Pena˜ ∗ Raul´ Sanchez´ Navarro y Abstract level of passing sequences distributions (cf [6,9,13]), by studying passing networks [3, 4, 8], or from a dy- Traditionally, most of football statistical and media namic perspective studying game flow [2], or pass- coverage has been focused almost exclusively on goals ing flow motifs at the team level [5], where passing and (ocassionally) shots. However, most of the dura- flow motifs (developed following [10]) were satis- tion of a football game is spent away from the boxes, factorily proven by Gyarmati, Kwak and Rodr´ıguez passing the ball around. The way teams pass the to set appart passing style from football teams from ball around is the most characteristic measurement of randomized networks. what a team’s “unique style” is. In the present work In the present work we ellaborate on [5] by ex- we analyse passing sequences at the player level, us- tending the flow motif analysis to a player level. We ing the different passing frequencies as a “digital fin- start by breaking down all possible 3-passes motifs gerprint” of a player’s style. The resulting numbers into all the different variations resulting from labelling provide an adequate feature set which can be used a distinguished node in the motif, resulting on a to- in order to construct a measure of similarity between tal of 15 different 3-passes motifs at the player level players. Armed with such a similarity tool, one can (stemming from the 5 motifs for teams). -

PSG Crush 10-Man Lyon to Reach French Cup Final Mbappe’S Treble Fires PSG Into Final

46 Friday Sports Friday, March 6, 2020 PSG crush 10-man Lyon to reach French Cup final Mbappe’s treble fires PSG into final LYON: Kylian Mbappe hit a hat-trick as Paris Lyon defenders before floating over a cross to Saint-Germain cruised into the final of the fellow forward Edinson Cavani, who controlled French Cup with a thumping 5-1 win at Lyon the ball only for Marcal to then handle before on Wednesday. The World Cup winner took the Uruguay striker could let his shot go. his goal tally in all competitions to 30 during Neymar slotted home the subsequent spot- a win that was eased by Fernando Marcal kick after confirmation of the handball by VAR, being sent off just before Neymar put the while Marcal had to leave the field after being French champions ahead in the 64th minute handed his second red card. “I prefer to say from the penalty spot. nothing about the penalty,” said Lyon boss The defeat Lyon ends a five-match unbeaten Rudi Garcia, who side face PSG in the League run that included an impressive 1-0 win over Ju- Cup final next month. “When you are 10 ventus in the Champions League and the week- against 11 playing such a strong team it’s no end’s triumph over local rivals Saint-Etienne. “It longer a contest.” was a solid, serious display full of concentra- Mbappe made sure of the Parisian’s visit to tion,” said PSG coach Thomas Tuchel. “After the the Stade de France next month with a superb Dortmund match (lost 2-1 in Germany), Mbappe solo effort with 20 minutes left, embarrassing has responded brilliantly. -

An Investigation of Best Practices in Youth Development Programmes at Selected Football Academies in the Western Cape

An Investigation of Best Practices in Youth Development Programmes at Selected Football Academies in the Western Cape. By Ashley Ian Jacobs 2444431 A full thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the Degree MAGISTER ARTIUM SPORT, RECREATION AND EXERCISE SCIENCE in the Department of Sport, Recreation and Exercise Science in the Faculty of Community and Health Sciences at the UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE Supervisor: Dr. Simone Titus October 2020 http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ Abstract Football around the globe has been used as a vehicle for youth development initiatives. Youth development programmes foster social change in communities and provide an ideal development context that often results in active sport participation. In South Africa, there are a number of youth development programmes that not only use football, but also other sporting codes to implement and create sustainable youth development programmes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore best practices in youth development programmes of selected football academies in the Western Cape. This study took place in the greater Cape Town area of the Western Cape and focused on selected football academies who administer youth development programmes. A qualitative approach was used to collect and analyse data for the study. Three key informant interviews and three focus group discussions were conducted with a total sample size of twenty-one participants from the three different academies. Focus group participants were purposively selected from the under fourteen, under sixteen and under eighteen teams from each football academy. The data from the study was collected and analysed through the lens of the Positive Youth Development perspective. -

Eight for Wood, 10 for Sa Derby

THURSDAY, APRIL 7, 2016 UNIFIED TRIES DEEPER WATER IN BAY SHORE EIGHT FOR WOOD, by Ben Massam Two years to the day after sending Centennial Farms= Wicked 10 FOR SA DERBY Strong (Hard Spun) north from his winter base at Palm Meadows to capture the GI Wood Memorial at Aqueduct, trainer Jimmy Jerkens is set to pull off a similar move with unbeaten >TDN Rising Star= Unified (Candy Ride {Arg}) in Saturday=s GIII Bay Shore S. at the Big A. Unified captured his six-furlong debut at Gulfstream in dominant wire-to-wire fashion Feb. 21 [video], and the trainer said the Centennial colorbearer has trained forwardly ahead of his second trip to the post. "He hasn't missed a beat,@ Jerkens said of the $325,000 Fasig- Tipton yearling purchase. AIt's a big step up, but we thought he has the talent. He=s done very well since then, so we're taking a shot." Cont. p4 Shagaf | NYRA/Labozzetta NO >DOUTE= ABOUT INGLIS SESSION TOPPER A full-brother to champion sprinter Lankan Rupee (Aus) >TDN Rising Star= Shagaf (Bernardini) will break from the rail as (Redoute=s Choice {Aus}) was the star turn on day two of the he puts his unbeaten record on the line against seven foes in Inglis Australian Easter Yearling Sale Wednesday. Saturday=s GI Wood Memorial S. at Aqueduct. The Shadwell Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. homebred, who annexed the local GIII Gotham S. last out Mar. 5, was installed as the 2-1 favorite on Eric Donovan=s morning line. -

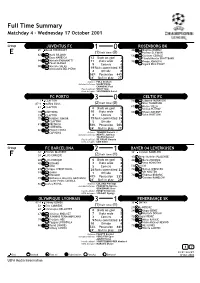

E 1 0 3 0 F 2 1

Full Time Summary Matchday 4 - Wednesday 17 October 2001 Group JUVENTUS FC ROSENBORG BK 25' David TREZEGUET 1046' in Dagfinn ENERLY (1)half time (0) out Hassan EL FAKIRI E in 62' Mark IULIANO in out 59' Christer GEORGE Enzo MARESCA 12 Shots on goal 2 out Harald Martin BRATTBAKK in 84' Michele PARAMATTI 11 Shots wide 4 in out 75' Frode JOHNSEN Pavel NEDVED 9 Corners 6 out Sigurd RUSHFELDT 90' in Marcelo SALAS out Alessandro DEL PIERO 19 Fouls committed 15 4 Offside 0 56% Possession 44% 34' Ball in play 27' Referee: POLL Graham Assistant referees: SHARP Philip CANADINE Paul Fourth official: WILEY Alan UEFA delegate: VERTONGEN Karel FC PORTO30 CELTIC FC 1' CLAYTON 56' in Lubomir MORAVCIK 45'+1 MÁRIO SILVA (2)half time (0) out Alan THOMPSON 61' CLAYTON 67' in Momo SYLLA 8 Shots on goal 0 out Stilian PETROV 10' CÔSTINHA 10 Shots wide 5 88' in Shaun MALONEY 19' CLAYTON 4 Corners 5 out John HARTSON 75' in RUBENS JUNIOR 15 Fouls committed 24 out CLAYTON 5 Offside 3 81' in FREDRICK 50% Possession 50% out CÔSTINHA 24' Ball in play 23' 86' in PAULO COSTA out CAPUCHO Referee: TEMMINK René H.J. Assistant referees: MEINTS Jantinus TALENS Berend Fourth official: DE GRAAF Hennie UEFA delegate: COX Eddie Group FC BARCELONA BAYER 04 LEVERKUSEN 12' Patrick KLUIVERT 2132' Carsten RAMELOW 38' LUIS ENRIQUE (2)half time (1) F 45' Diego Rodolfo PLACENTE 20' LUIS ENRIQUE 6 Shots on goal 5 46' in Boris ZIVKOVIC out 48' in GERARD 3 Shots wide 6 Jens NOWOTNY out XAVI 5 Corners 4 53' LUCIO 69' Philippe CHRISTANVAL 28 Fouls committed 22 76' in Zoltan SEBESCEN out -

12 National Teams Will Participate in the Tournament, Represent

FAQs Participating Teams and Players How many teams will participate? 12 national teams will participate in the tournament, representing many of the biggest football nations on the planet to create a truly global competitive international tournament. How many players will be in each squad? Each Star Sixes squad will comprise ten players, six will be permitted to play at any one time with the other four being substitutes. When will the teams be confirmed and announced? The 12 countries have been confirmed - Brazil, China, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Nigeria, Portugal, Scotland and Spain. Who will manage the teams? Each Star Sixes team will have an appointed captain who will play and also manage the side. How are players chosen? The selection process is managed by the team captains and Star Sixes. When will players be announced? A galaxy of stars has already been announced, including: Roberto Carlos (Brazil), Steven Gerrard, Michael Owen, David James, Emile Heskey (England), Carles Puyol, Gaizka Mendieta (Spain), Michael Ballack (Germany), Deco (Portugal), Robert Pires (France), Jay-Jay Okocha (Nigeria) and Dominic Matteo (Scotland). Keep an eye on the Star Sixes website and social media for further player announcements in the coming weeks. What kit will the players wear? Players will wear national team colours, designed specifically for the Star Sixes tournament. Keep an eye on the Star Sixes website and social media to find out when the team kits will be revealed. Competition Format, Schedule and Rules What is the competition format? How do teams progress to the final? There will be three groups of four teams. -

Bloodstock Agent Moore Preparing for the Future | 2 | Monday, June 29, 2020

Monday, June 29, 2020 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here THE WEEK AHEAD - PAGE 15 GLOBAL GROUP 1 RACES - PAGE 18 YESTERDAY'S RACE RESULTS - PAGE 21 Bloodstock agent Moore Read Tomorrow's Issue For: preparing for the future Stallion Watch Son of champion Hong Kong trainer looking ahead with What's on business model set for change in coming months Race meetings: Albury (NSW), Taree (NSW), Wangaratta (VIC) Barrier trials/ Jump-outs: Albury (NSW), Taree (NSW), Cranbourne (VIC) International meetings: Yarmouth (UK), Windsor (UK), Thirsk (UK), Limerick (IRE), Kilbeggan (IRE), Kenilworth (SAF) International sales: Fasig-Tipton Midlantic 2YOs In Training Sale (US) George Moore INGLIS MORNING BRIEFING prevent any international visitors who are not BY ANDREW HAWKINS | @ANZ_NEWS already in the country from being at Inglis’ Great Southern Sale he Inglis Australian Easter Warwick Farm complex, creating a different moved to Sydney Yearling Sale Round 2, to be held market for a prized group of yearlings. Inglis announced yesterday that the Great in conjunction with the Inglis Among those who will be absent is Hong Southern Sale, which was set to be held in Scone Yearling Sale at Riverside Kong-based bloodstock agent George Moore, Melbourne, will be brought forward and StablesT on Sunday, will be the latest unusual with quarantine ensuring that he is logistically conducted in Sydney on July 9 in the wake of a quirk in a sales season that has been upended, unable to be in Sydney for the sale before spike on Covid-19 cases in Victoria. “Following rearranged and impacted heavily by the returning to the Asian mecca as his father John significant consultation with vendors and buyers, Covid-19 pandemic. -

DAVID BABUNSKI Right Wing

CV Updated 06.10.2015 Curriculum Vitae DAVID BABUNSKI Right Wing Players passport: Full name David Babunski Place of birth Skopje, FYR Macedonia Date of birth 01th March 1994 Height/ Weight 174 cm/ 68 kg Position Right Wing Sec.position Attacking Midfielder Foot Right Nationality FYR Macedonia Spain (EU) Current club FC Barcelona B Competition Segunda Division B, Grupo III National team FYR Macedonia U 21 National team career, appearance, goals: Selection FYR Macedonia A team 06 00 Selection FYR Macedonia U 21 16 04 Selection FYR Macedonia U 19 03 01 Selection FYR Macedonia U 17 04 00 Golden Goal Sports Management LLC Football Scouting, Consulting and Management © 2015 All Rights GGSM LLC | www.goldengoal.sm | [email protected] Last two season`s, National Championships, appearance, assists, goals: 2014-2015 FC Barcelona B Spain 2. 22 01 03 2013-2014 FC Barcelona B Spain 2. 19 00 01 Transfer history: Jul 2013 Barca Juvenil A, Spain - Barcelona B, Spain Jul 2011 Barca Juvenil B, Spain - Barca Juvenil A, Spain Barcelona Cadete A, Spain - Barca Juvenil B, Spain Market value (by Transfermarkt): Oct 2015 500 000 Euro (EMU) Highest Market value (by Transfermarkt): Oct 2013 600 000 Euro (EMU) Contract until: FC Barcelona B Jun 2016 Additional Information: Joined FC Barcelona school “La Masia” in 2006, with just 12 years turned on. In December 2011 elected as best Young Sportsman of FYR Macedonia for that year. Born brother of Dorian, who plays in Real Madrid Youth Academy. Golden Goal Sports Management LLC Football Scouting, Consulting