Reconsiderations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

Accused: Fairfield’S Witchcraft Trials September 25, 2014 – January 5, 2015 Educator Guide

Accused: Fairfield’s Witchcraft Trials September 25, 2014 – January 5, 2015 Educator Guide Accused: Fairfield’s Witchcraft Trials September 25, 2014 – January 5, 2015 Teacher Guide Index Introduction: The Legacy of Witchcraft Page 3 Essential Questions & Big Ideas Page 5 Accused Suggested Mini-Activity Page 6 Online Teacher Resources: Lesson Plans & Student Activities Page 7 Student & Teacher Resources: Salem Pages 9 - 10 New England Witchcraft Trials: Overview & Statistics Page 10 New England Witchcraft Timeline Pages 12 - 13 Vocabulary Page 14 Young Adult Books Page 15 Bibliography Page 15 Excerpts from Accused Graphic Novel Page 17 - 19 Educator Guide Introduction This Educator Guide features background information, essential questions, student activities, vocabulary, a timeline and a booklist. Created in conjunction with the exhibition Accused: Fairfield’s Witchcraft Trials, the guide also features reproductions of Jakob Crane’s original illustrations and storylines from the exhibition. The guide is also available for download on the Fairfield Museum’s website at www.fairfieldhistory.org/education This Educator Guide was developed in partnership with regional educators at a Summer Teacher Institute in July, 2014 and co-sponsored by the Fairfield Public Library. Participants included: Renita Crawford, Bridgeport, CT Careen Derise, Discovery Magnet School, Bridgeport, CT Leslie Greene, Side By Side, Norwalk, CT Lauren Marchello, Fairfield Ludlowe High School, Fairfield, CT Debra Sands-Holden, King Low Heywood Thomas School, Stamford, CT Katelyn Tucker, Shelton Public Schools, CT About the Exhibition: In 17th century New England religious beliefs and folk tradition instilled deep fears of magic, evil, and supernatural powers. How else to explain unnatural events, misfortune and the sudden convulsions and fits of local townspeople? In this exhibition, the fascinating history of Connecticut’s witchcraft trials is illuminated by author and illustrator Jakob Crane. -

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

The Physician and Witchcraft in Restoration England

THE PHYSICIAN AND WITCHCRAFT IN RESTORATION ENGLAND by GARFIELD TOURNEY THE YEAR of 1660 witnessed important political and scientific developments in England. The restoration of the monarchy and the Church of England occurred with the return of Charles II after the dissolution of the Commonwealth and the Puritan influence. The Royal Society, after informal meetings for nearly fifteen years, was established as a scientific organization in 1660 and received its Royal Charter in 1662. During the English revolution, and for a short time during the Commonwealth, interest in witchcraft mounted. Between 1645 and 1646 Matthew Hopkins acquired the reputation as the most notorious witch-finder in the history of England.I His activities in Essex and the other eastern counties led to the execution of as many as 200 witches. In Suffolk it is estimated that he was responsible for arresting at least 124 persons for witchcraft, of whom 68 were hanged. The excesses soon led to a reaction and Hopkins lost his influence, and died shortly thereafter in 1646. There then was a continuing decline in witchcraft persecutions, and an increasing scepticism toward the phenomena of witchcraft was expressed. Scepticism was best exemplified in Thomas Hobbes' (1588-1679) Leviathan, published in 1651.2 Hobbes presented a materialistic philosophy, emphasizing change occurring in motion, the material nature of mental activity, the elimination of final causes, and the rejection of the reality of spirit. He decried the belief in witchcraft and the supematural, emphasizing -

The Autobiography of Increase Mather

The Autobiography of Increase Mather I-DÎTED BY M. G. HALL j^ STRETCH a point to call this maTiuscript an W autobiography. Actually it i.s a combinatioa of aiito- biograpliy and political tract and journal, in which the most formal part comes first and the rest was added on lo it as occasion offered. But, the whole is certainly auto- biographical and covers Increase Mather's life faithfull}'. It was tlie mainstay of Cotton Mather's famous biograpliy Pareniator, which appeared in 1724, and of Kenneth Mur- dock's Increase Miiîher, whicli was published two liundred and one years later.^ Printing the autobiography Jiere is in no way designed to improve or correct Mather's biog- raphers. They have done well by him. But their premises and purposes were inevitabiy different from liis. I'he present undertaking is to let Increase Matlier also be lieard on tlie subject of himself. Readers who wish to do so are invited to turn witliout more ado to page 277, where tliey may read the rjriginal without interruption. For tjiose who want to look before they leap, let me remind tliem of tlie place Increase Mather occu[!Íes in tlie chronology of his family. Three generations made a dy- nasty extraordhiary in any country; colossal in the frame of ' Cotton Msther, Pami'.at'^r. Mnnoirs if Remarkables in the Life and Death o/ the F.vtr- MemorahU Dr. Increase Múíker (Boston, 1724). Kenneth B. Murdock, Incrfasr Mathfr, the Foremost .Imerican Puritan (Cambridge, 1925)- Since 1925 three books bearing importantly on hicrcase Mather have been published: Thomas J. -

The Crucible, Arthur Miller, and the Salem Scenic Designer‘S Notes Witch Trials

TPAC Education’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee presents THE CRUCIBLE Teacher Guidebook 2 Adventure 3 Properties, G.P. Country Music Association Allstate Corrections Corporation of America American Airlines Creative Artists Agency Bank of America Curb Records Baulch Family Foundation The Danner Foundation AT&T Davis-Kidd Booksellers, Inc. BMI Dell Computers Bridgestone Firestone Trust Fund DEX Imaging, Inc. Brown-Forman Dollar General Corporation Caterpillar Financial Services Corporation Enterprise Rent-A-Car Foundation CBRL Group Foundation Patricia C. & Thomas F. Frist Designated Central Parking Corporation Fund* The Coca-Cola Bottling Company Gannett Foundation The Community Foundation of Middle Gaylord Entertainment Foundation Tennessee Gibson Guitar Corp. The Joel C. Gordon & Bernice W. Gordon Family Foundation The HCA Foundation on behalf of the HCA and TriStar Family of Hospitals The Hermitage Hotel Ingram Arts Support Fund* THANK Ingram Charitable Fund Martha & Bronson Ingram Foundation* Lipman Brothers, Inc. YOU Juliette C. Dobbs 1985 Trust Tennessee Performing Arts LifeWorks Foundation Center gratefully The Memorial Foundation acknowledges the generous Metro Action Commission support of corporations, Metropolitan Nashville Arts Commission foundations, government Miller & Martin, LLP agencies, and other groups Nashville Gas, a Piedmont Company and individuals who have Nashville Predators Foundation contributed to TPAC National Endowment for the Arts in partnership Education in 2007-2008. with the Southern Arts Federation New -

Torrey Source List

Clarence A Torrey - Genealogy Source List TORREY SOURCE LIST A. Kendrick: Walker, Lawrence W., ―The Kendrick Adams (1926): Donnell, Albert, In Memoriam . (Mrs. Family,‖ typescript (n.p., 1945) Elizabeth (Knight) Janverin Adams) (Newington, N.H., A. L. Usher: unidentified 1926) A. Morgan: Morgan Gen.: Morgan, Appleton, A History Adams-Evarts: Adams, J. M., A History of the Adams and of the Family of Morgan from the Year 1089 to Present Evarts Families (Chatham, N.Y.: Courier Printing, Times by Appleton Morgan, of the Twenty-Seventh 1894) Generation of Cadivor-Fawr (New York: privately Adams-Hastings: Adams, Herbert Baxter, History of the printed, [1902?]) Thomas Adams and Thomas Hastings Families (Amherst, Abbe-Abbey: Abbey, Cleveland, Abbe-Abbey Genealogy: Mass.: privately printed, 1880) In Memory of John Abbe and His Descendants (New Addington: Harris, Thaddeus William, ―Notes on the Haven, Conn.: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1916) Addington Family,‖ Register 4 (April 1850) Abbott: Abbott, Lemuel Abijah, Descendants of George Addington (1931): Addington, Hugh Milburn, History of Abbott of Rowley, Mass. of His Joint Descendants with the Addington Family in the United States and England: George Abbott, Sr., of Andover, Mass.; of the Including Many Related Families: A Book of Descendants of Daniel Abbott of Providence, R.I., 2 Compliments (Nickelsville, Va.: Service Printery, 1931) vols. (n.p.: privately printed, 1906) Adgate Anc.: Perkins, Mary E., Old Families of Norwich, Abell: Abell, Horace A., One Branch of the Abell Family Connecticut, MDCLX to MDCCC (Norwich, Conn., Showing the Allied Families (Rochester, N.Y., 1934) 1900) Abington Hist.: Hobart, Benjamin, History of the Town of Agar Anc.: unidentified Abington, Plymouth County, Mass. -

The Woman in the Wilderness the Further Development of Christian Apocalypticism

1 The Woman in the Wilderness The Further Development of Christian Apocalypticism I am the Alpha and Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end. — The Revelation of John, 22:13 Pope Urban II stood before an extraordinary assemblage of high Church officials and French nobles at Clermont in 1095 to implore them to come to the aid of Constantinople, beleaguered by a Seljuk Turkish army, and then liberate the holy city of Jerusalem from Muslim rule. “[A] race from the kingdom of the Persians, an accursed race, a race wholly alienated from God” has long occupied the spiritual seat of Christendom, slaughtering God’s chil- dren “by pillage and fire,” he reminded them in stark, ominous tones. They have taken many survivors into doleful slavery “into their own country” and “have either destroyed the churches of God or appropriated them for the rites of their own religion.” In language that was pointedly both apocalyptic and millenarian, Urban rallied the French nobles, who reportedly cried out, “God wills it! God wills it” as he promised that the Christian recovery of Jerusalem would mark the advent of the Millennium. While the French nobility was likely more motivated by the prospect of conquering “a land flowing with milk and honey,” commoners and peasants throughout Western Europe took the eschatological significance of what became the First Crusade to their hearts. With bloodthirsty zeal the crusading armies harried and massacred Rhineland German Jews on their way to Constantinople in 1096, some of the Christians doubtless taking literally the prediction in Revelation 19 that all who did not follow Christ would be “slain by the sword.” This notion further inspired them in the war against the Muslim population of Palestine as they carved out the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem by 1099, and embarked upon subsequent crusades that have come to characterize the history of medieval A Dream of the Judgment Day. -

60 Ft John Alden Gaff Double Topsail Schooner 1939/1946 - Sold

HERITAGE, VINTAGE AND CLASSIC YACHTS +44 (0)1202 330 077 60 FT JOHN ALDEN GAFF DOUBLE TOPSAIL SCHOONER 1939/1946 - SOLD Specification DIRIGO II 60 FT JOHN ALDEN GAFF DOUBLE TOPSAIL SCHOONER 1939/1946 Designer John G Alden Length waterline 45 ft 0 in / 13.72 m Engine Yanmar 4JH2-UTE 100 HP Builder Goudy & Stevens, E Boothbay, Maine Beam 15 ft 7 in / 4.75 m Location USA Date 1939 Draft 7 ft 10 in / 2.39 m Price Sold Length overall 72 ft 0 in / 21.95 m Displacement 49 Tonnes Length deck 60 ft 5 in / 18.41 m Construction Carvel, plank on frame These details are provisional and may be amended Specification BROKER'S COMMENTS DIRIGO II is a fully functional classic schooner yacht of impeccable pedigree, still sailing the ocean doing what she was intended and built for - which is to take family, friends, and crew on adventures: voyaging and sailing in style, in both communal and private comfort, and safely. Two major structural refits under present ownership since 2010 leave this handsome and proven schooner a long way from retirement sitting at a dock as another pretty face. In fact her 2019 summer cruise was 6200 miles from Mexico back to the Maine waters of her birth, and taking part in three regattas once there, proving just what a capable and seaworthy family passagemaker DIRIGO II is – still doing exactly what she was conceived for by John G Alden in 1939. • SANDEM AN YACHT COMPANY • • Brokerage Of Classic & Vintage Yachts • www.sandemanyachtcompany.co.uk © Sandeman Yacht Company Limited 2021. -

Cb20 2016 Key16.Key.Pdf

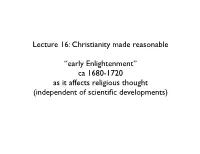

Lecture 16: Christianity made reasonable ! “early Enlightenment” ca 1680-1720 as it affects religious thought (independent of scientific developments) ! Some assessments of English intellectual climate: ! Bishop Sprat in 1667: "the influence which Christianity once obtained on men's minds is now prodigiously decayed." ! Thomas Burnet, a bishop's son, in 1719: "I cannot but remind you with joy how the world has changed since the time when, as we know, a word against the clergy passed for rank atheism, and now to speak tolerably of them passes for superstition." ! ! they agree on decline in respect for traditional religion and clergy; they disagree on assessing this change John Thornton Kirkland, Increase Mather, president president of Harvard, of Harvard, 1685-1701 1810-28: a unitarian orthodox Calvinist Cotton Mather, son of Increase (1663-1728) Cotton Mather: God visits punishments and rewards on humans through the workings of nature and special providence End of executions for religious heterodoxy: ! Giordano Bruno - 1600 ! Salem, 1692: 22 people executed for witchcraft but protests against the legal procedures were lodged throughout the process. Increase Mather questioned use of spectral evidence; Cotton Mather mostly defended the trials. 1703 convictions that could be (e.g. excommunications) were reversed; 1722 symbolic compensation paid to families of victims ! End of executions for religious heterodoxy: ! ! 1697 Thomas Aikenhead, a Scottish student, was last person executed in Britain for blasphemy: denied that Bible is sacred, denied -

Crown V. Susannah North Martin Court of the County of Essex, Colony of Massachusetts Salem, Year of Our Lord 1692

Crown v. Susannah North Martin Court of the County of Essex, Colony of Massachusetts Salem, Year of Our Lord 1692 Case Description and Brief Susannah Martin was born in Buckinghamshire, England in 1621. She was the fourth daughter, and youngest child, of Richard North and Joan (Bartram) North. Her mother died when she was a young child, and her father remarried a woman named Ursula Scott. In 1639, at the age of 18, Susannah and her family came to the United States, settling in Salisbury, Massachusetts. Richard North, a highly respected man, was listed as one of the first proprietors and founders of Salisbury On August 11, 1646, Susannah, now 24, married the widower George Martin, a blacksmith. Making their home in Salisbury, the couple had a loving marriage, that produced nine children, one of which died in infancy. Prosperous in business, George and Susannah became one of the largest landholders of the region. George died in 1686, leaving Susannah a widow. After her husband’s death she managed his estate and lands with acumen and talent. As a young woman she was known for her exceptional beauty. Descriptions of Susanna say that she was short, active, and of remarkable personal neatness. She was also said to be very outspoken, contemptuous of authority, and defiant in the face of challenge. Due to her attractiveness and family’s prosperity, she had been the target of jealous slander, which had followed her for years, all of which had been proven unfounded. In January 1692, a a group of young girls began to display bizarre behavior in nearby Salem, Massachusetts. -

An Interdisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Research

Knighted An Interdisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Research 2021 Issue 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………………….1 Introduction Welcome, Editorial Board, Mission, Submission Guidelines…………………………….2 Shakespeare’s Socioeconomics of Sack: Elizabethan vs. Jacobean as depicted by Falstaff in Henry IV, Part I, Christopher Sly in The Taming of the Shrew, and Stephano in The Tempest…………………………………………………………………………….Sierra Stark Stevens…4 The Devil Inside……...……………………………………………………...Sarah Istambouli...18 Blade Runner: The Film that Keeps on Giving…………………………..………Reid Vinson...34 Hiroshima and Nagasaki: A Necessary Evil….……………………..…………….Peter Chon…42 When Sharing Isn’t Caring: The Spread of Misinformation Post-Retweet/Share Button ……………………………………………………………...…………………Johnathan Allen…52 Invisible Terror: How Continuity Editing Techniques Create Suspense in The Silence of the Lambs…………………………………………………………………………..……..Garrentt Duffey…68 The Morality of Science in “Rappaccini’s Daughter” and Nineteenth- CenturyAmerica…………………………………………………………………Eunice Chon…76 Frederick Douglass: The Past, Present, and Future…………………………...Brenley Gunter…86 Identity and Color Motifs in Moonlight………………………………..................Anjunita Davis…97 Queerness as a Rebel’s Cause……………….………………………….Sierra Stark Stevens…108 The Deadly Cost of Justification: How the Irish Catholic Interpretation of the British Response to “Bloody Sunday” Elicited Outrage and Violence, January–April 1972……Garrentt Duffey…124 Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement: How Young Students