130 the Taming of the Great Barrier Reef

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company The geology of the Mabuyag Island Group and its part in the geological evolution of Torres Strait Friedrich VON GNIELINSKI von Gnielinski, F. -

Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 by Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane

ARCHIVE: Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 By Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane The date of the cyclone refers to the day of landfall or the day of the major impact if it is not a cyclone making landfall from the Coral Sea. The first number after the date is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) for that month followed by the three month running mean of the SOI centred on that month. This is followed by information on the equatorial eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures where: W means a warm episode i.e. sea surface temperature (SST) was above normal; C means a cool episode and Av means average SST Date Impact January 1858 From the Sydney Morning Herald 26/2/1866: an article featuring a cruise inside the Barrier Reef describes an expedition’s stay at Green Island near Cairns. “The wind throughout our stay was principally from the south-east, but in January we had two or three hard blows from the N to NW with rain; one gale uprooted some of the trees and wrung the heads off others. The sea also rose one night very high, nearly covering the island, leaving but a small spot of about twenty feet square free of water.” Middle to late Feb A tropical cyclone (TC) brought damaging winds and seas to region between Rockhampton and 1863 Hervey Bay. Houses unroofed in several centres with many trees blown down. Ketch driven onto rocks near Rockhampton. Severe erosion along shores of Hervey Bay with 10 metres lost to sea along a 32 km stretch of the coast. -

PUB. 143 Sailing Directions (Enroute)

PUB. 143 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ WEST COAST OF EUROPE AND NORTHWEST AFRICA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Springfield, Virginia © COPYRIGHT 2014 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2014 FIFTEENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 II Preface date of the publication shown above. Important information to amend material in the publication is updated as needed and 0.0 Pub. 143, Sailing Directions (Enroute) West Coast of Europe available as a downloadable corrected publication from the and Northwest Africa, Fifteenth Edition, 2014 is issued for use NGA Maritime Domain web site. in conjunction with Pub. 140, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) North Atlantic Ocean and Adjacent Seas. Companion 0.0NGA Maritime Domain Website volumes are Pubs. 141, 142, 145, 146, 147, and 148. http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal 0.0 Digital Nautical Charts 1 and 8 provide electronic chart 0.0 coverage for the area covered by this publication. 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 4 October 2014, manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a including Notice to Mariners No. 40 of 2014. Subsequent course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of or- updates have corrected this publication to 24 September 2016, igin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the including Notice to Mariners No. -

MOONBI Is the Newsletter of Fraser Island Defenders Organization Limited

MOONBI is the newsletter of Fraser Island Defenders Organization Limited. The word Moonbi is the Butchulla name of the central part of their homeland, K’gari. FIDO, “The Watchdog of Fraser Island", aims to ensure the wisest use of Fraser Island’s natural resources A warm welcome to all you new FIDO members and, to long-standing FIDO members, thank you for your loyalty and patience. It’s been a long time since the last IN THIS ISSUE: MOONBI was published, in The importance of MOONBI ........ Page 2 November 2018 , shortly before Tribute to John Sinclair AO .......... Page 2 the passing of FIDO’s founder, Reflections from the President .... Page 3 Memorial Lecture 2020 ............... Page 5 inspiration and driving force, John Be like John – Write! .................... Page 7 Sinclair. This issue of MOONBI is FINIA............................................. Page 11 FIDO Executive ............................. Page 12 especially dedicated to the John Sinclair - The early days ....... Page 13 memory of John and his New Members ............................. Page 15 Vale Lew Wyvill QC ...................... Page 16 remarkable life, and also to the FIDO Weedbusters ....................... Page 17 continuing commitment of FIDO to K’gari dingo research ................... Page 18 Don and Lesley Bradley................ Page 20 celebrate and protect the many Memories of John Sinclair ........... Page 21 John Sinclair’s Henchman ............ Page 22 World Heritage values of K’gari. Access K’gari during COVID.......... Page 24 FIDO's Registered -

Four Months in a Sneak-Box

Four Months in a Sneak-Box Nathaniel H. Bishop The Project Gutenberg EBook of Four Months in a Sneak-Box, by Nathaniel H. Bishop (#2 in our series by Nathaniel H. Bishop) Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Four Months in a Sneak-Box Author: Nathaniel H. Bishop Release Date: May, 2004 [EBook #5686] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on August 7, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, FOUR MONTHS IN A SNEAK-BOX *** This eBook was produced by Bruce Miller FOUR MONTHS IN A SNEAK-BOX. A BOAT VOYAGE OF 2600 MILES DOWN THE OHIO AND MISSISSIPPI RIVERS, AND ALONG THE GULF OF MEXICO. -

Between Australia and New Guinea-Ecological and Cultural

Geographical Review of Japan Vol. 59 (Ser. B), No. 2, 69-82, 1986 Between Australia and New Guinea-Ecological and Cultural Diversity in the Torres Strait with Special Reference to the Use of Marine Resources- George OHSHIMA* The region between lowland Papua and the northern tip of the Australian continent presents a fascinating panorama of ecological, cultural and socio-economic diversity. In lowland Papua and on its associated small islands such as Saibai, Boigu and Parama, a combination of coastal forests and muddy shores dominates the scene, whereas the Torres Strait Islands of volcanic and limestone origin, together with raised coral islands and their associated reef systems present a range of island ecosystems scattered over a broad territory some 800km in extent. Coralline habitats extend south wards to the Cape York Peninsula and some parts of Arnhem Land. Coupled with those ecological diversities within a relatively small compass across the Torres Strait, the region has evoked important questions concerning the archaeological and historical dichotomy between Australian hunter-gatherers and Melanesian horticulturalists. This notion is also reflectd in terms of its complex linguistic, ethnic and political composition. In summarizing the present day cultural diversity of the region, at least three major components emerge: hunter-gatherers in the Australian Northern Territory, Australian islanders and tribal Papuans. Historically, these groups have interacted in complex ways and this has resulted in an intricate intermingling of cultures and societies. Such acculturation processes operating over thousands of years make it difficult to isolate meaning ful trends in terms of "core-periphery" components of the individual cultures. -

Net Primary Productivity, Global Climate Change and Biodiversity In

This file is part of the following reference: Fuentes, Mariana Menezes Prata Bezerra (2010) Vulnerability of sea turtles to climate change: a case study within the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/11730 Vulnerability of sea turtles to climate change: A case study with the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population PhD thesis submitted by Mariana Menezes Prata Bezerra FUENTES (BSc Hons) February 2010 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences James Cook University Townsville, Queensland 4811 Australia “The process of learning is often more important than what is being learned” ii Statement of access I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library, via the Australian Theses Network, or by other means allow access to users in other approved libraries. I understand that as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction access to this thesis. _______________________ ____________________ Signature, Mariana Fuentes Date iii Statement of sources declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ________________________ _____________________ Signature, Mariana Fuentes Date iv Statement of contribution of others Research funding: . -

Steenstrupia ZOOLOGICAL MUSEUM UNIVERSITY of COPENHAGEN

Steenstrupia ZOOLOGICAL MUSEUM UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN Volume 2: 49-90 No. 5: January 25, 1972 Brachyura collected by Danish expeditions in south-eastern Australia (Crustacea, Decapoda) by D. J. G. Griffin The Australian Museum, Sydney Abstract. A total of 73 species of crabs are recorded mainly from localities ranging from the southern part of the Coral Sea (Queensland) through New South Wales and Victoria to the eastern part of the Great Australian Bight (South Australia). Four species are new to the Australian fauna, viz. Ebalia (E.) longimana Ortmann, Oreophorus (O.) ornatus Ihle, Aepiniis indicus (Alcock) and Medaeus planifrons Sakai. Ebalia (Phlyxia) spinifera Miers, Stat.now is raised to rank of species; Philyra undecimspinosa (Kinahan), comb.nov. includes P. miinayeitsis Rathbun, syn.nov. and Eumedonits villosus Rathbun is a syn.nov. of E. cras- simatuis Haswell, comb.nov. Lectotypes are designated for Piiggetia mosaica Whitelegge, PiluDvuis australis Whitelegge and P. moniUfer Haswell. Notes on morphology, taxonomy and general distribution are included. From 1909 to 1914 the eastern and southern parts of the Australian continental shelf and slope were trawled by the Fisheries Investigation Ship "Endeavour". Dr. Th. Mortensen, during his Pacific Expedition of 1914-16, collected speci mens from the decks of the ship as it was working along southern New South Wales during the last year of this survey and visited several other localities along the coasts of New South Wales and Victoria. The Crustacea Brachyura collected by the "Endeavour" were reported on by Rathbun (1918a, 1923) and by Stephenson & Rees (1968b). Rathbun's reports, dealing with a total of 88 species (including 23 new species), still provide a very important source of information on eastern and southern Australian crabs, the only other major report dealing with the crabs of this area being Whitelegge's (1900) account of the collections taken by the "Thetis" along the New South Wales coast in the late 1800's. -

Land & Sea Management Strategy

LAND & SEA MANAGEMENT STRATEGY for TORRES STRAIT Funded under the Natural Heritage Trust LAND & SEA MANAGEMENT STRATEGY for TORRES STRAIT Torres Strait NRM Reference Group with the assistance of Miya Isherwood, Michelle Pollock, Kate Eden and Steve Jackson November 2005 An initiative funded under the Natural Heritage Trust program of the Australian Government with support from: the Queensland Department of Natural Resources & Mines the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage and the Torres Strait Regional Authority. Prepared by: Bessen Consulting Services FOREWORD The Torres Strait region is of enormous significance from a land and sea management perspective. It is a geographically and ecologically unique region, which is home to a culturally distinct society, comprised of over 20 different communities, extending from the south-western coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG) to the northern tip of Cape York Peninsula. The Torres Strait is also a very politically complex area, with an international border and a Treaty governance regime that poses unique challenges for coordinating land and sea management initiatives. Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people, both within and outside of the region, have strong and abiding connections with their land and sea country. While formal recognition of this relationship has been achieved through native title and other legal processes, peoples’ aspirations to sustainably manage their land and sea country have been more difficult to realise. The implementation of this Strategy, with funding from the Australian Government’s Natural Heritage Trust initiative, presents us with an opportunity to progress community-based management in our unique region, through identifying the important land and sea assets, issues, information, and potential mechanisms for supporting Torres Strait communities to sustainably manage their natural resources. -

Four Months in a Sneak-Box : a Boat Voyage of 2600 Miles Down The

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY ILLINOiS RISTORICAI SURVEY Four Months in a Sneak- Box. A BOAT VOYAGE OF 260O MILES DOWN THE OHIO AND MISSISSIPPI RIVERS, AND ALONG THE GULF OF MEXICO. BY NATHANIEL H. BISHOP, AUTHOR OF "a THOUSAND MILEs' WALK ACROSS SOUTH AMERICA,' ANU '"VoVAOE OK THE PAl'ER CANUii." BOSTON: LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS. NEW YORK: CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM. 1S79. COPYRIGHT, 1S79, By Nathaniel II. Bishop. Electrotyped at the Boston Stereotype Foundry, 19 Spring Laue. TO THE OFFICERS AND EMPLOYEES OF THE LIGHT HOUSE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE UNITED STATES Sbls ^ook is pcb'uatcb BY ONE WHO HAS LEARXED TO RESPECT THEIR HONEST, INTELLIGENT AND EFFICIENT LABORS IN SERVING THEIR GOVERNMENT, THEIR COUNTRYMEN, AND MANKIND GENERALLY. 1085S7 — INTRODUCTION. Eighteen months ago the author gave to the " public his Voyage of the Paper Canoe : — a geographical journey of 25oo miles from Ql'ebec to the Gulf of Mexico, during the YEARS 1874-5." The kind reception by the American press of the author's first journey to the great southern sea, and its republication in Great Britain and in France within so short a time of its appearance in the United States, have encouraged him to give the public a companion volume, "Four Months in A Sneak-Box," — which is a relation of the expe- riences of a second cruise to the Gulf of INIexico, but by a different route from that followed in the " Voyage of the Paper Canoe." This time the author procured one of the smallest and most com- fortable of boats — a purely American model, devel- oped bv the bay-men of the New Jersey coast of the United States, and recently introduced to the gunning V VI INTRODUCTION. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

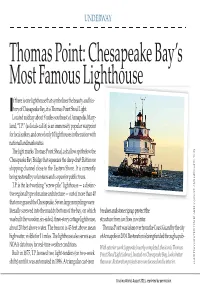

Thomas Point: Chesapeake Bay's Most Famous Lighthouse

UNDERWAY Thomas Point: Chesapeake Bay’s Most Famous Lighthouse f there is one lighthouse that symbolizes the beauty and his‐ I tory of Chesapeake Bay, it is Thomas Point Shoal Light. Located midbay about 8 miles southeast of Annapolis, Mary‐ land, “T.P.” (as locals call it) is an immensely popular waypoint for local sailors, and one of only 10 lighthouses in the nation with national landmark status. ) The light marks Thomas Point Shoal, a shallow spit below the TOP Chesapeake Bay Bridge that squeezes the deep‐draft Baltimore shipping channel close to the Eastern Shore. It is currently OPPOSITE, being restored by volunteers and is open for public tours. AND T.P. is the last working “screw‐pile” lighthouse — a distinc‐ tive regional type of marine architecture — out of more than 40 VE (ABO that once graced the Chesapeake. Seven large iron pilings were Y literally screwed into the muddy bottom of the bay, on which breaker and stone riprap protect the BLAKEL was built the wooden, six‐sided, three‐story cottage lighthouse, structure from ice floes in winter. about 20 feet above water. The beacon is 43 feet above mean Thomas Point was taken over from the Coast Guard by the city STEPHEN high water, visible for 11 miles. The lighthouse also serves as an of Annapolis in 2004. Restoration is being funded through a pub‐ OF NOAA data buoy for real‐time weather conditions. With exterior work (opposite) nearly completed, the iconic Thomas Y Built in 1875, T.P. housed two light‐tenders (on two‐week Point Shoal Light (above), located on Chesapeake Bay, looks better TES shifts) until it was automated in 1986.