Chapter 06--Sammern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dangerous Disorder: 'Confusione' in Sixteenth- Century Italian Art Treatises

Dangerous disorder: ‘confusione’ in sixteenth- century Italian art treatises Caroline Anjali Ritchie In sixteenth-century Italian writing on art, confusione is a much-maligned concept. While many scholars skim over the word, swiftly pressing on to examine neutral or positively charged words like composizione, varietà or grazia, the connotations of confusione as used in Renaissance art treatises are far from self-evident.1 Particularly in the second half of the cinquecento, writers used the word confusione to express manifold concerns regarding the supposedly detrimental effects of confused and hence confusing artworks upon the beholder’s enjoyment or pleasure, as well as upon their intellectual, psychological, and spiritual experiences. The profusion of cinquecento instances of the word, in the treatises of artistic practitioners and non- practitioners, is potentially symptomatic of writers’ reactions against so-called ‘mannerism’ and their concerns about the perceived decline or senescence of art; more explicitly, some important instances are bound up in counter-reformation debates about sacred images. Most fundamentally, considered in the context of Renaissance art theory and faculty psychology, confusione indicates the prevalent fears surrounding inherently ‘bad’ artistic qualities. I thus begin not with artworks but with the words that writers used to describe artworks. Such words are revealing of the ‘broad phenomena’ of responses that David Freedberg expounded as the stuff of legitimate historical inquiry.2 I argue specifically that images were also thought to reveal their efficacy through a perceived formal defectiveness, as distinct from the kind of morally dubious subject matter examined by Freedberg in relation, for example, to Savonarola’s burning of ‘profane’ images.3 Words like confusione, expressing negative value-judgements about the quality of artworks, can help to detect and diagnose the concerns of their users regarding the potentially malign powers of images considered defective. -

Hacia El Dialogo Della Pittura Lodovico Dolce Y Sus Lettere Di Diversi (1554 - 1555)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal de Revistas Científicas Complutenses Hacia el Dialogo della Pittura Lodovico Dolce y sus Lettere di diversi (1554 - 1555) Santiago ARROYO ESTEBAN Real Academia de España en Roma [email protected] Recibido: 4 de Marzo de 2009 Aceptado: 24 de Junio de 2009 RESUMEN Acercamiento a la prehistoria del Dialogo della pittura de Lodovico Dolce (1557), prestando especial atención a su relación con las cartas de Miguel Ángel, Rafael y Tiziano incluidas en las Lettere di diversi (1554) recopiladas por el literato. Se traducen y comentan en Apéndice las cartas de sujeto artístico aparecidas en la segunda edición de las Lettere (1555) que Dolce dirige a Gasparo Ballini y Alessandro Contarini. Palabras Clave: Lodovico Dolce. Cartas. Diálogo de la pintura. Gasparo Ballini. Alessandro Contarini. Tiziano. Rafael. Miguel Ángel. Literatura artística. Teoría. Ut pictura poësis. Ékphrasis. Venus y Adonis. Variedad. Inven- ción. Dibujo. Colorido. To the Dialogo della pittura: Lodovico Dolce and his Lettere di diversi of 1554-1555 ABSTRACT Approach to the prehistory of the Dialogo della pittura by Lodovico Dolce (1557), paying special attention to its connection with the letters by Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian included in the Lettere di diversi (1554) compiled by the writter. In Appendix also the translation into Spanish and comment of the letters of artistic argument that appeared in the second edition of the Lettere (1555) which Dolce addressed to Gasparo Ballini and Alessandro Contarini. Key Words: Lodovico Dolce. Lettere. Dialogo della pittura. Gasparo Ballini. Alessandro Contarini. -

Ontdek Schilder, Tekenaar, Prentkunstenaar Otto Van Veen

79637 4 afbeeldingen Otto van Veen man / Noord-Nederlands, Zuid-Nederlands schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, hofschilder Naamvarianten In dit veld worden niet-voorkeursnamen zoals die in bronnen zijn aangetroffen, vastgelegd en toegankelijk gemaakt. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld andere schrijfwijzen, bijnamen of namen van getrouwde vrouwen met of juist zonder de achternaam van een echtgenoot. Vaenius, Octavius Vaenius, Otho Vaenius, Otto Veen, Octavius van Veen, Otho van Venius, Octavius Venius, Otho Venius, Otto Kwalificaties schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, hofschilder Nationaliteit/school Noord-Nederlands, Zuid-Nederlands Geboren Leiden 1556 Thieme/Becker 1940; according to Houbraken 1718: born in 1558 Overleden Brussel 1629-05-06 Houbraken 1718, vol. 1, p. Rombouts/Van Lerius 1872/1961, vol.1, p. 375, note 3 Familierelaties in dit veld wordt een familierelatie met één of meer andere kunstenaars vermeld. son of Cornelis Jansz. van Veen (1519-1591) burgomaster of Leyden and Geertruyd Simons van Neck (born 1530); marrried with Maria Loets/Loots/Loos (Duverger 1992, vol. 6, p. 186-187); brother of Gijsbert, Pieter, Artus and Aechtjen Cornelis; father of Gertrude van Veen; his 6-year old son Cornelis was buried on 19 September 1605 in St. Jacob's Church Zie ook in dit veld vindt u verwijzingen naar een groepsnaam of naar de kunstenaars die deel uitma(a)k(t)en van de groep. Ook kunt u verwijzingen naar andere kunstenaars aantreffen als het gaat om samenwerking zonder dat er sprake is van een groep(snaam). Dit is bijvoorbeeld het geval bij kunstenaars die gedeelten in werken van een andere kunstenaar voor hun rekening hebben genomen (zoals bij P.P. -

Isabel Clara Eugenia and Peter Paul Rubens’S the Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series

ABSTRACT Title of Document: PIETY, POLITICS, AND PATRONAGE: ISABEL CLARA EUGENIA AND PETER PAUL RUBENS’S THE TRIUMPH OF THE EUCHARIST TAPESTRY SERIES Alexandra Billington Libby, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archeology This dissertation explores the circumstances that inspired the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, Princess of Spain, Archduchess of Austria, and Governess General of the Southern Netherlands to commission Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series for the Madrid convent of the Descalzas Reales. It traces the commission of the twenty large-scale tapestries that comprise the series to the aftermath of an important victory of the Infanta’s army over the Dutch in the town of Breda. Relying on contemporary literature, studies of the Infanta’s upbringing, and the tapestries themselves, it argues that the cycle was likely conceived as an ex-voto, or gift of thanks to God for the military triumph. In my discussion, I highlight previously unrecognized temporal and thematic connections between Isabel’s many other gestures of thanks in the wake of the victory and The Triumph of the Eucharist series. I further show how Rubens invested the tapestries with imagery and a conceptual conceit that celebrated the Eucharist in ways that symbolically evoked the triumph at Breda. My study also explores the motivations behind Isabel’s decision to give the series to the Descalzas Reales. It discusses how as an ex-voto, the tapestries implicitly credited her for the triumph and, thereby, affirmed her terrestrial authority. Drawing on the history of the convent and its use by the king of Spain as both a religious and political dynastic center, it shows that the series was not only a gift to the convent, but also a gift to the king, a man with whom the Infanta had developed a tense relationship over the question of her political autonomy. -

Learned Love Sance

The emblem is a wonderful invention of the Renais- Learned Love sance. The funny, mysterious, moralizing, learned or pious combinations of word and image in the Learned Love crossover emblematic genre can be characterized as a delicate network of motifs and mottoes. This network served as a receptacle for the traditions of the European visual and literary arts. In its turn it Proceedings of the Emblem Project Utrecht Conference on influenced architecture, painting, love poetry, chil- dren’s books, preaching and interior decoration. Dutch Love Emblems and the Internet (November 2006) Together emblem books and the culture to which they belong form a web of closely interre- lated references. It is surely no coincidence that digitised emblem books are popular items on what may be their modern counterpart: the World Wide Web. In 2003 the Emblem Project Utrecht set out to digitise 25 representative Dutch love emblem books. The love emblem is one of the best known emblem- atic subgenres, first developed in the Low Countries and soon popular all over Europe. To celebrate the completion of the work done by the Emblem Project Utrecht, a conference was held on November 6 and 7, 2006. The focus of this con- ference was twofold: the Dutch love emblem and the process of digitising the emblems. This volume contains the selected papers of this conference, com- plemented by a general introduction and additional papers by the editors. Stronks and Boot DANS (Data Archiving and Networked Services) is the national organization in the Netherlands for storing and providing permanent access to research data from the humanities and social sciences. -

Dsm Magazine

CONTACT US SUBSCRIBE SUBMIT PHOTOS PAST ISSUES SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTIONS IA MAGAZINE ARTS DSM MAR/APR 2018 Lost and Found An unlikely investigation uncovers the naked truth behind a hidden treasure. ARTS Lost and Found ! " # 0 Showstoppers HOME ARTS DINING FASHION PEOPLE COMMUNITY NEWSLETTERS CALENDAR ! Facebook " Twitter # Pinterest Above: Skin, hair and fabric all share a fresh glow in this detail from a valuable artwork that languished in the shadows under centuries of darkened varnish and the grunge of time. Writer: Vicki L. Ingham Photographer: Duane Tinkey A dingy old painting pulled from a gloomy nook is about to experience a bright new life, with a new identity and a new value, enjoying it all from a perch on a wall at Hoyt Sherman Place. In many ways, the painting known as “Apollo and Venus” is a lottery winner in the art world, an instant celebrity plucked from obscurity by chance, destiny or mysterious intervention. Hoyt Sherman will unveil the restored painting March 21 at a special event (see details, page 146). As you may recall when we introduced the artwork in a previous dsm story, Hoyt Sherman’s executive director, Robert Warren, had been rummaging through a stash of old stuff, looking for Civil War flags, when he spotted some paintings tucked behind a table. One of them, a large, unsigned, oil-on-wood panel depicting a mythological scene, looked intriguing, he says, “so we pulled it out and put it on the table, thinking we’d go back to it.” Later, a member of the art and archives committee noticed it and texted Warren, saying, “I seem to recall that piece might be valuable.” As Warren wrapped the painting for protection, he noticed an auction tag on the back, identifying the work by name and attributing it to Italian artist Federico Barocci (1526-1612). -

The Leiden Collection

Emperor Commodus as Hercules ca. 1599–1600 and as a Gladiator oil on panel Peter Paul Rubens 65.5 x 54.4 cm Siegen 1577 – 1640 Antwerp PR-101 © 2017 The Leiden Collection Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator Page 2 of 11 How To Cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. "Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator." InThe Leiden Collection Catalogue. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017. https://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/. This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2017 The Leiden Collection Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator Page 3 of 11 Peter Paul Rubens painted this bold, bust-length image of the eccentric Comparative Figures and tyrannical Roman emperor Commodus (161–92 A.D.) within an illusionistic marble oval relief. In stark contrast to his learned father Marcus Aurelius (121–80 A.D.), known as “the perfect Emperor,” Commodus, who reigned from 180 until he was murdered on New Year’s Eve of 192 at the age of 31, proudly distinguished himself by his great physical strength.[1] Toward the end of his life, Commodus went further than any of his megalomaniac predecessors, including Nero, and identified himself with Hercules, the superhumanly strong demigod of Greek mythology famous for slaughtering wild animals and monsters with his bare hands. According to the contemporary historian Herodian of Antioch (ca. -

Lodovico Dolce's Somma Della Filosofia D'aristotele and The

Addressing the Reader: Lodovico Dolce’s Somma della filosofia d’Aristotele and the Audience for Vernacular Philosophy in Sixteenth-Century Italy Lodovico Dolce’s popularization of Aristotelian philosophy, the Somma della filosofia d’Aristotele, was published in Venice around 1565. It is a rather loosely organised compendium of philosophical material, comprising books on logic, practical philosophy (ethics, economics, and politics) and natural philosophy. It has not been much studied,1 and yet offers valuable insights into both the vernacularization of Aristotelian philosophy and the increasingly sophisticated ways, often through the use of paratext, that sixteenth-century authors (working together with editors and publishers) sought to appeal to and communicate with their audience. This article will examine the differing readerships foreseen for the Somma della filosofia d’Aristotele and how the work seeks to persuade, mollify or rebuff these readers. The Somma della filosofia d’Aristotele serves as an example of the ways Renaissance authors and publishers sought to shape readings of a work of popularized philosophy, and Dolce, as a poligrafo accustomed to writing for a commercial audience, shows a particularly keen awareness of the “diverse quality” (Somma 3: 97v) of readers which might encounter the text; this diversity is addressed with overtures intended for his cultured but non-scholarly readers, his learned critics, and those who might take issue with his work on religious grounds. In his magisterial Aristotle and the Renaissance, Charles Schmitt demonstrated not only the persistence of Aristotelianism as a philosophical force in the Renaissance but also the tradition’s variety, subtlety and ability to adapt to changed intellectual and cultural circumstances. -

Abstracts of Amsterdam 2010 Conference Workshops

HNA in Amsterdam - "Crossing Boundaries" Workshop Summaries Rethinking Riegl Jane Carroll [email protected] Alison Stewart [email protected] In 1902, Alois Riegl wrote the Urquelle for all subsequent studies of Northern European group portraits, Das holländische Gruppenporträt. In that work, Riegl expanded art history beyond the contemporary emphasis on formalism and stylistic evolution. Drawing upon his interest in the relationship of objects within a work, Riegl asked his readers to expand that idea to include the viewer of art as an active participant in the understanding of visual works, an element he called “attentiveness.” In short, Riegl's book crossed the accepted boundary of what art history could consider and made viewing art a living exchange between present and past, and between viewer and object. Since its publication, all who have dealt with group portraiture have had to come into dialogue with Riegl’s book. In 1999, the Getty responded to a revived interest in Riegl's theories and republished The Group Portraiture of Holland in a new translation with historical introduction by Wolfgang Kemp. This reissuing increased the accessibility of Riegl’s work and reintroduced him to new generations of art historians. Prompted by that volume, we would like to gather together a group of scholars before the extensive collection of group portraits in the Amsterdams Historisch Museum. The venue of their Great Hall seems a perfect spot in which to reexamine the larger claims of Riegl’s work, and discuss current understandings of Dutch group portraiture. In keeping with the conference theme, we will explore how this genre crosses such boundaries as public vs. -

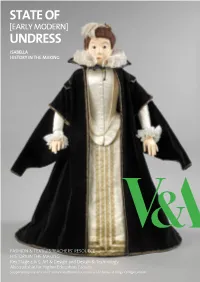

History in the Making – Isabella

ISABELLA HISTORY IN THE MAKING FASHION & TEXTILES TEACHERS’ RESOURCE HISTORY IN THE MAKING Key Stage 4 & 5: Art & Design and Design & Technology Also suitable for Higher Education Groups Supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council with thanks to Kings College London 1 FOREPART (PANEL) LIMEWOOD MANNEQUIN BODICE CHOPINES (SHOES) SLEEVE RUFFS GOWN NECK RUFF & REBATO HEADTIRE FARTHINGALE STOCKINGS & GARTERS WIG SMOCK 2 3 4 5 Contents Introduction: Early Modern Dress 9 Archduchess Isabella 11 Isabella undressing / dressing guide 12 Early Modern Materials 38 6 7 Introduction Early Modern Dress For men as well as women, movement was restricted in the Early Modern period, and as you’ll discover, required several The era of Early Modern dress spans between the 1500s to pairs of hands to put on. the 1800s. In different countries garments and tastes varied hugely and changed throughout the period. Despite this variation, there was a distinct style that is recognisable to us today and from which we can learn considerable amounts in terms of design, pattern cutting and construction techniques. Our focus is Europe, particularly Belgium, Spain, Austria and the Netherlands, where our characters Isabella and Albert lived or were connected to during their reign. This booklet includes a brief introduction to Isabella and Albert and a step-by-step guide to undressing and dressing them in order to gain an understanding of the detail and complexity of the garments, shoes and accessories during the period. The clothes you see would often be found in the Spanish courts, and although Isabella and Albert weren’t particularly the ‘trend-setters’ of their day, their garments are a great example of what was worn by the wealthy during the late 16th and early 17th centuries in Europe. -

The Representation of Martyrdoms During the Early Counter-~Eformation in Antwerp

DAVID FREEDBERG The Representation of Martyrdoms During The Early Counter-~eformationin Antwerp NO one who has passed through those rooms in the Antwerp closed doors, to prevent any of the disorderliness which had Gallery which contain the works of the generation before marked the riotous behaviour of 1566. When Alexander Rubens can fail to have been impressed by a group of vivid Farnese, the victorious Prince of Parma, finally regained and often gruesomely depicted martyrdoms. They are, control of Antwerp in 1585, Catholic services were restored notably (and for the time being I give the current Gallery yet again, and the guilds and local churches busily started attributions) : The Marbrdom of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, by setting up their desecrated altars anew.6 Some of the older Hieronymus Francken (Fig.2 ;centre panel of an altar-piece), paintings were returned, but most had been lost in the The ChariQ and Marordam of Saints Cosmas and Damian (Fig.3; intervening period, either through neglect or, occasionally, as wings of an altar-piece) ,Diocletiancondemns St Sebastian to Death a result of wanton destruction. Again, new commissions were and St Sebastian beaten with Rods (Figs.8 and 9; reverse of the signed, and this time it was the first generation of Franclien wings of an altar-piece), and Two Scenes from the Ilfartyrdom brothers - Hieronymus, Frans, and Ambrosius - wlio of St George (Fig. 10; wings of an altar-piece), all by Ambro- profited most.' We cannot deal with all such replacement sius Francken. altars here; let us examine, rather, the scenes of martyrdom As far as I know, the taste for martyrdoms in Antwerp at which so often formed their subject. -

Dallas Museum of Art Biombo: Elite Spanish Identity and Hybridity in 18Th Century Colonial Latin America

Dallas Museum of Art Biombo: Elite Spanish Identity and Hybridity in 18th Century Colonial Latin America Author: Jonathan A. Molina Garcia Faculty Mentor: Kelly Donahue-Wallace Ph.D, Department of Art Education and Art History; College of Visual Arts and Design Department and College Affiliation: Department of Art Education and Art History; College of Visual Arts and Design Dallas Museum of Art Biombo 2 Bio: Born in San Salvador, El Salvador, Jonathan A. Molina Garcia is currently pursuing dual undergraduate degrees in photography and art history. His photographic works have been selected for various juried exhibitions including the annual Voertman’s Student Art Exhibition, 500x Gallery, and the Rockport Center for the Arts. In the Spring of 2013, he received the Arch and Anne Giles Kimbrough Fund Award from the Dallas Museum of Art, an SPESC Student Travel scholarship, and a creative project grant from the College of Visual Arts and Design in addition to three separate departmental scholarships in both his studio and art history majors. In addition, he has contributed essays for exhibition catalogs at Holly Johnson Gallery in Dallas, Texas. In the upcoming Fall semester, he plans to apply for admission into a master of fine arts program to pursue photography with a focus on an interdisciplinary practice and visual critical studies. Dallas Museum of Art Biombo 3 Abstract: First appearing in the Americas in the early 17th century, the folding screens of New Spain, or biombos as they are known in Spanish, would come to embellish the homes and palaces of the elite and join a litany of other precious objects as must-have accessories for secular spaces.