Downloaded As a Consolidated Dataset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situation Report #2, Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 March 25, 2003 Note: the Last Situation Report Was Dated November 18, 2002

U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) BURUNDI – Complex Emergency Situation Report #2, Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 March 25, 2003 Note: The last situation report was dated November 18, 2002. BACKGROUND The Tutsi minority, which represents 14 percent of Burundi’s 6.85 million people, has dominated the country politically, militarily, and economically since national independence in 1962. Approximately 85 percent of Burundi’s population is Hutu, and approximately one percent is Twa (Batwa). The current cycle of violence began in October 1993 when members within the Tutsi-dominated army assassinated the first freely elected President, Melchoir Ndadaye (Hutu), sparking Hutu-Tutsi fighting. Ndadaye’s successor, Cyprien Ntariyama (Hutu), was killed in a plane crash on April 6, 1994, alongside Rwandan President Habyarimana. Sylvestre Ntibantunganya (Hutu) took power and served as President until July 1996, when a military coup d’etat brought current President Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) to power. Since 1993, an estimated 300,000 Burundians have been killed. In August 2000, nineteen Burundian political parties signed the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Arusha, Tanzania, overseen by peace process facilitator, former South African President Nelson Mandela. The Arusha Peace Accords include provisions for an ethnically balanced army and legislature, and for democratic elections to take place after three years of transitional government. The three-year transition period began on November 1, 2001. President Pierre Buyoya is serving as president for the first 18 months of the transition period, to be followed in May 2003 by a Hutu president for the final 18 months. -

The Mineral Industry of Burundi in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook BURUNDI [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior January 2020 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Burundi By Thomas R. Yager In 2016, the production of mineral commodities—notably can be found in previous editions of the U.S. Geological Survey gold, tantalum, tin, and tungsten—represented only a minor Minerals Yearbook, volume III, Area Reports—International— part of the economy of Burundi (United Nations Economic Africa, which are available at https://www.usgs.gov/centers/ Commission for Africa, 2017). The legislative framework for nmic/africa-and-middle-east. the mineral sector in Burundi is provided by the Mining Code of Burundi (law No. 1/21 of October 15, 2013). The legislative Reference Cited framework for the petroleum sector is provided by the Mining United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2017, Burundi, in African and Petroleum Act of 1976. Data on mineral production are statistical yearbook 2017: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, in table 1. Table 2 is a list of major mineral industry facilities. p. 113–117. (Accessed November 7, 2018, at https://www.uneca.org/sites/ More-extensive coverage of the mineral industry of Burundi default/files/PublicationFiles/asyb-2017.pdf.) TABLE 1 BURUNDI: PRODUCTION OF MINERAL COMMODITIES1 (Metric tons, gross weight, unless otherwise specified) Commodity2 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 METALS Gold, mine, Au contente kilograms 500 400 500 500 500 Niobium and tantalum, mine, columbite-tantalite concentrate: Gross weight do. 258,578 73,518 105,547 53,093 r 31,687 Nb contente do. 51,000 14,000 21,000 10,000 r 6,200 Ta contente do. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP OF BURUNDI I INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 II THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGROUPMENT CAMPS ...................................... 2 III OTHER CAMPS FOR DISPLACED POPULATIONS ........................................ 4 IV HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DURING REGROUPMENT ......................... 6 Extrajudicial executions ......................................................................................... 6 Property destruction ............................................................................................... 8 Possible prisoners of conscience............................................................................ 8 V HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN THE CAMPS ........................................... 8 Undue restrictions on freedom of movement ......................................................... 8 "Disappearances" ................................................................................................... 9 Life-threatening conditions .................................................................................. 10 Insecurity in the context of armed conflict .......................................................... 11 VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DISGUISED AS PROTECTION ................ 12 VII CONCLUSION.................................................................................................... 14 VIII RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................................... 15 -

Health Food Security HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES

Burundi • Humanitarian Bi-Monthly report Situation Report #04 Date/Time 28 May 2009 This report was issued by Burundi office. It covers the period from 11 to 24 May 2009. The next report will be issued on or around 9 June 2009. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES - MSF prepares the phase out of its emergency nutritional operation in Kirundo Province - Repatriation from last Burundian camp in Rwanda - New refugee camp in Bwagiriza I. Situation Overview The President of Burundi has officially requested the support (logistical, technical, financial and moral) of the United Nations for the preparation and the organisation of the 2010 elections. Since March, doctors have been strike over their salaries. Developments in South Kivu and the forthcoming operation Kimia II against FDLR, are not expected to have a major impact on Burundi. The IACP contingency plan remains valid and will be updated in September. II. Humanitarian Needs and Response Health MSF is preparing to phase out its emergency nutrition programme in the Kirundo province as it expects the situation to improve as the harvests ongoing. MSF has also noted that children being referred to its nutritional centres are not as severely malnourished as when it started its emergency programme. Since February 9th, 2009; over 480 children were admitted to the nutritional stabilisation centre because of acute severe malnutrition with medical complications; some 28 children were lost because their situation was too critical when they arrived at the stabilisation centre. During this emergency nutrition programme, MSF found that 58% of the children admitted had oedemas and systematic testing of incoming patients also showed that 53.2% also had malaria. -

BURUNDI COUNTRY REPORT October 2003 Country

BURUNDI COUNTRY REPORT October 2003 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Burundi October 2003 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the document 1.1 – 1.4 2 Geography 2.1 3 Economy 3.1 – 3.3 4 History Summary of events since independence 4.1 – 4.4 Outbreak of Civil War 4.5 – 4.7 Coup of 25 July 1996 4.8 – 4.9 Peace Talks 4.10 – 4.18 Failed Coup attempts of 18 April 2001 and 22 July 2001 4.19 – 4.20 Developments prior to term of Transitional Government 4.21 – 4.24 The Transitional Government 4.25 – 4.48 Cantonment 4.49 – 4.50 5. State Structures The Constitution 5.1 – 5.2 Citizenship and Nationality 5.3 Political System 5.4 – 5.10 Judiciary 5.11 – 5.15 Legal Rights/Detention 5.16 – 5.23 Death Penalty 5.24 Internal Security 5.25 Armed Forces 5.26 – 5.30 "Gardiens de la Paix" 5.31 – 5.33 Self defence programmes 5.34 – 5.36 "Self Defence in Solidarity" 5.37 Weapons training for civilians 5.38 South African Protection Support Detachment 5.39 – 5.40 Prisons and prison conditions 5.41 – 5.44 Military Service 5.45 – 5.47 Conscientious Objectors and Deserters 5.48 – 5.49 Medical Services 5.50 – 5.52 HIV/AIDS 5.53 – 5.54 People with disabilities 5.55 – 5.56 Educational System 5.57 – 5.63 6 Human Rights 6.A Human Rights issues Overview 6.1 – 6.6 Torture 6.7 – 6.11 Extrajudicial Killings 6.12 – 6.22 Disappearances 6.23 Abuses by Rebel groups 6.24 – 6.30 Human Rights Organisations 6.31 – 6.32 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.33 – 6.35 Media Institutions 6.36 – 6.40 Journalists 6.41 – 6.49 Freedom of Religion -

January 2018

JANUARY 2018 This DTM report has been funded with the generous support of the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA), the Department for International Development (DFID/UKaid) and the Swiss Agen- cy for Development and Cooperation (SDC). TABLE OF CONTENTS DTM Burundi Methodology..……….…………………………………...……………….…….…..1 IDP Presence Map…..………..…………………………………………………………..…..…….2 Highlights.……………………………………………………………………………….….….…..3 Provinces of Origin..………………………………………………………………………..….…..4 Return Intentions…………………………………….……………………………………....……5 Displacement Reasons.….……………………………………………………………….…..……6 New Displacements……..……………………………………………………………….….…….7 Displacement Trends……..…………………………………………………………….……….…8 Humanitarian Overview: Health and Food Security.………………………………………..…….9 Humanitarian Overview: Livelihoods and WASH.....……..……………….……………….……..10 Humanitarian Overview: Education and Protection……..…..……………...…………....………11 IDP Shelter Types………………………..………………………….…………………..……...…12 Shelter Construction Materials……….……………………….………...……………...….……..13 Precarious Conditions in IDP homes…….……...………………………………….…...…...…...15 Natural Disaster Cycle…….……………..…………………………...……………………..…....16 Provincial Profiles.…………………………………………………………………………….….17 Contact Information……………………………………………………………………………..18 The IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix is a comprehensive system DTM METHODOLOGY implemented to analyse and disseminate information to better unders- tand movements and needs of Internally Displaced Persons in Burundi. 1 Volunteers from the Burundian Red Cross consult -

Intimidate and Harass Political Opponents

Burundi “We’ll Tie You Up HUMAN and Shoot You” RIGHTS WATCH Lack of Accountability for Political Violence in Burundi “We’ll Tie You Up and Shoot You” Lack of Accountability for Political Violence in Burundi Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-634-9 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2010 1-56432-634-9 “We’ll Tie You Up and Shoot You” Lack of Accountability for Political Violence in Burundi Glossary of Terms and Acronyms ................................................................................................ 1 Note on Administrative Structures ......................................................................................... 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................... -

1996 Human Rights Report: Burundi Page 1 of 13

1996 Human Rights Report: Burundi Page 1 of 13 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Burundi Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1996 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1997. BURUNDI Burundi's democratically elected president was overthrown in a military coup on July 25. Despite the coup, the National Assembly and political parties continue to operate, although under constraints. The present regime, under the self-proclaimed interim President, Major Pierre Buyoya, abrogated the 1992 Constitution and, during the so-called Transition Period, replaced the 1994 Convention of Government with a decree promulgated on September 13. Under this decree, the National Assembly does not have the power to remove the President of the Republic. The Prime Minister, appointed by the President, replaces the President in the event of the President's death or incapacity. Under the former constitution, the President of the National Assembly replaced the President. Buyoya holds power in conjunction with the Tutsi-dominated military establishment. The judicial system remains under the control of the Tutsi minority, and most citizens consider it biased against Hutus. Violent conflict among Hutu and Tutsi armed militants and the army plunged the country into a civil war marked by ethnic violence, which included fighting between the army and armed rebel groups. -

Burundi Page 1 of 18

Burundi Page 1 of 18 Burundi Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 Burundi is a republic ruled by a Transitional Government established under the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Accord (Arusha Accord) in November 2001. On April 30, the second half of the 3-year Transitional Government began as Domitien Ndayizeye, a member of the Hutu ethnic group, succeeded Pierre Buyoya, a member of the Tutsi ethnic group, as President. In 2001, a Transitional Constitution was adopted, providing for power to be shared between the Tutsi minority, which has traditionally ruled the country, and the Hutu majority. A presidential decree suspended elections in 1998; however, the Transitional Constitution provides for elections following the completion of the 3-year Transitional Government. The country remained engaged in a low-intensity civil conflict, and for most of the year, the conflict involved two armed opposition groups, the National Council for Defense of Democracy– Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) faction led by Pierre Nkurunziza, and the Palipehutu/National Liberation Front (FNL) faction led by Agathon Rwasa. Smaller factions of both groups had signed and implemented ceasefire agreements with the Transitional Government in October 2002. In December 2002, the largest armed opposition group, the Nkurunziza faction of the CNDD-FDD, also signed a ceasefire with the Transitional Government. In October, the Transitional Government and the CNDD-FDD faction led by Nkurunziza signed a protocol on power-sharing, and in November, the CNDD-FDD entered the Transitional Government, assuming four cabinet positions and other posts. -

PEPFAR Burundi Country Operational Plan (COP) 2017

PEPFAR Burundi Country Operational Plan (COP) 2017 Strategic Direction Summary April 29, 2017 Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 2.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 2.2 Investment profile 2.3 Sustainability Profile 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 2.5 Stakeholder engagement 3.0 Geographic and population prioritization 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-up Locations and Populations 4.1 Targets for scale-up locations and populations 4.2 Priority population prevention 4.3 Preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) 4.4HIV testing and counseling (HTC) 4.5 Facility and community-based care and support 4.6 TB/HIV 4.7 Adult treatment 4.8 Pediatric Treatment 4.9 TB/HIV 4.10 Addressing COP17 Technical Considerations 4.11 Commodities 4.12 Collaboration, Integration and Monitoring 5.0 Program Activities in Attained and Sustained Locations and Populations (Note: In COP 2017, Burundi does not have attained or sustained SNUs) 6.0 Program Support Necessary to Achieve Sustained Epidemic Control 6.1 Critical systems investments for achieving key programmatic gaps 6.2 Critical systems investments for achieving priority policies 6.3 Proposed system investments outside of programmatic gaps and priority policies 7.0 USG Management, Operations and Staffing Plan to Achieve Stated Goals Appendix A - Prioritization Appendix B - Budget Profile and Resource Projections Appendix C - Tables and Systems Investments for Section 6.0 Page -

After-Action Review

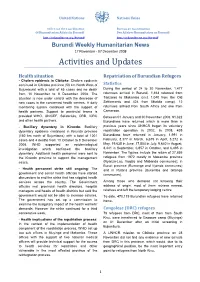

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination Bureau de Coordination Of Humanitarian Affairs in Burundi Des Affaires Humanitaires au Burundi http://ochaonline.un.org/Burundi http://ochaonline.un.org/Burundi Burundi Weekly Humanitarian News 17 November - 07 December 2008 Activities and Updates Health situation Repatriation of Burundian Refugees - Cholera epidemic in Cibitoke: Cholera epidemic continued in Cibitoke province (50 km North West of Statistics Bujumbura) with a total of 65 cases and no death During the period of 24 to 30 November, 1,477 from 10 November to 8 December 2008. The returnees arrived in Burundi. 1,464 returned from situation is now under control with the decrease of Tanzania to Makamba (incl. 1,040 from the Old new cases in the concerned health centres. A daily Settlements and 424 from Mtabila camp). 12 monitoring system continued with the support of returnees arrived from South Africa and one from health partners. Support to provincial teams is Cameroon. provided WHO, UNICEF, Solidarités, CRB, ICRC Between 01 January and 30 November 2008, 91,322 and other health partners. Burundians have returned which is more than in - Bacillary dysentery in Kirundo: Bacillary previous years since UNHCR began its voluntary dysentery epidemic continued in Kirundo province repatriation operation in 2002. In 2008, 435 (150 km north of Bujumbura) with a total of 1201 Burundians have returned in January, 1,991 in cases and 4 deaths from 10 October to 8 December February, 8,377 in March, 6,675 in April, 5,272 in 2008. WHO supported an epidemiological May, 19,635 in June, 17,504 in July, 9,640 in August, investigation which confirmed the bacillary 8,441 in September, 6,857 in October, and 6,495 in dysentery. -

Integrated Health Project in Burundi (IHPB) Contract Number: AID-623-C-14-00001

Integrated Health Project in Burundi (IHPB) Contract Number: AID-623-C-14-00001 Quarterly Report January – March 2017 Submitted by: FHI 360 and partners Submission date: April 30, 2017 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 CLIN 1: Increased Positive Behaviors at the Individual, Household and Community Levels ......................................... 10 Sub-CLIN 1.1: Improved key behavioral pre-determinants at the individual, household and community levels ..... 10 Sub-CLIN 1.2: Increased accessibility and availability of health products to individuals and households ................ 15 Sub-CLIN 1.3: Strengthened support for positive gender norms and behavior and increased access to GBV services ................................................................................................................................................................................. 19 CLIN 2: Increased Use of Quality Integrated Health and Support Services ................................................................... 25 Sub-CLIN 2.1: Increased access to health and support services within communities............................................... 25 Sub-CLIN 2.2: Increased percent of facilities that provide quality