This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh, C. 1710–70

Edinburgh Research Explorer Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70 Citation for published version: Paul, T 2013, 'Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70', The Economic History Review, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 226-248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Economic History Review Publisher Rights Statement: © Paul, T. (2013). Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70. The Economic History Review, 66(1), 226-248. 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 © Paul, T. (2013). Credit, reputation, and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh, c. 1710–70. The Economic History Review, 66(1), 226-248. 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00652.x Credit, reputation and masculinity in British urban commerce: Edinburgh c. -

Ashley Walsh

Civil religion in Britain, 1707 – c. 1800 Ashley James Walsh Downing College July 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. All dates have been presented in the New Style. 1 Acknowledgements My greatest debt is to my supervisor, Mark Goldie. He encouraged me to study civil religion; I hope my performance vindicates his decision. I thank Sylvana Tomaselli for acting as my adviser. I am also grateful to John Robertson and Brian Young for serving as my examiners. My partner, Richard Johnson, and my parents, Maria Higgins and Anthony Walsh, deserve my deepest gratitude. My dear friend, George Owers, shared his appreciation of eighteenth- century history over many, many pints. He also read the entire manuscript. -

Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 10 July 2017 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 10 July 2017 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 10 July 2017 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 10 July 2017 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 26 June 2017 Tuesday 5 September 2017 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by Scottish Government Business followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 6 September 2017 2:00 pm Parliamentary Bureau Motions 2:00 pm Portfolio Questions Finance and Constitution; Economy, Jobs and Fair Work followed by Scottish Government Business followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' -

The European Cities Hotel Forecast 23 Appendix: Methodology 43 Contacts 47

www.pwc.com/hospitality Best placed to grow European cities hotel forecast 2011 & 2012 October 2011 NEW hotel forecast for 17 European cities In this issue Introduction 4 Key findings 5 Setting the scene 6 The cities best placed to grow 7 Economic and travel outlook 15 The European cities hotel forecast 23 Appendix: methodology 43 Contacts 47 PwC Best placed to grow 3 Introduction Europe has the biggest hotel and travel market in the world, but its cities and its hotel markets are undergoing change. Countries and cities alike are being buffeted by new economic, social, technological, environmental and political currents. Europe has already begun to feel the winds of change as the old economic order shifts eastwards and economic growth becomes more elusive. While some cities struggle, hotel markets in other, often bigger and better connected cities prosper. For many countries provincial markets have been hit harder than those in the larger cities. In this report we look forward to 2012 and ask which European cities’ hotel sectors are best placed to take advantage of the changing economic order. Are these the cities of the so called ‘old’ Europe or the cities of the fast growing ‘emerging’ economies such as Istanbul and Moscow? What will be driving the growth? What obstacles do they face? Will the glut of new hotel rooms built in the boom years prove difficult to digest? The 17 cities in this report are all important tourist destinations. Some are capitals or regional centres, some combine roles as leading international financial and asset management centres, transportation hubs or tourism and conference destinations. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction. -

French Travellers to Scotland, 1780-1830

French Travellers to Scotland, 1780-1830: An Analysis of Some Travel Journals. Elizabeth Anne McFarlane Submitted according to regulations of University of Stirling January 2015 Abstract. This study examines the value of travellers’ written records of their trips with specific reference to the journals of five French travellers who visited Scotland between 1780 and 1830. The thesis argues that they contain material which demonstrates the merit of journals as historical documents. The themes chosen for scrutiny, life in the rural areas, agriculture, industry, transport and towns, are examined and assessed across the journals and against the social, economic and literary scene in France and Scotland. Through the evidence presented in the journals, the thesis explores aspects of the tourist experience of the Enlightenment and post - Enlightenment periods. The viewpoint of knowledgeable French Anglophiles and their receptiveness to Scottish influences, grants a perspective of the position of France in the economic, social and power structure of Europe and the New World vis-à-vis Scotland. The thesis adopts a narrow, focussed analysis of the journals which is compared and contrasted to a broad brush approach adopted in other studies. ii Dedication. For Angus, Mhairi and Brent, who are all scientists. iii Acknowledgements. I would like to thank my husband, Angus, and my daughter, Mhairi, for all the support over the many years it has taken to complete this thesis. I would like to mention in particular the help Angus gave me in the layout of the maps and the table. I would like to express my appreciation for the patience and perseverance of my supervisors and second supervisors over the years. -

City of Edinburgh Council

SUBMISSION FROM THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL INTRODUCTION This submission from the City of Edinburgh Council is provided in response to the Local Government and Communities Committee’s request for views on the proposed National Planning Framework 2. The sections in this statement that refer to the Edinburgh Waterfront are also supported by members of the Edinburgh Waterfront Partnership. To assist the Committee, the Council has prepared a series of proposed modifications to the text of NPF2 which are set out in an Annex. SUMMARY The City of Edinburgh Council welcomes the publication of NPF2 and commends the Scottish Government for the considerable efforts it has made in engaging with key stakeholders throughout the review period. However, the Council requests that NPF2 is modified to take account of Edinburgh’s roles as a capital city and the main driver of the Scottish economy. This is particularly important in view of the current economic recession which has developed since NPF2 was drafted. In this context it is important that Edinburgh’s role is fully recognised in addressing current economic challenges and securing future prosperity. It should also recognise that the sustainable growth of the city-region depends critically on the provision of the full tram network and affordable housing. In addition, the Council considers that the scale and significance of development and change at Edinburgh’s Waterfront is significantly downplayed. As one of the largest regeneration projects in Europe it will be of major benefit to the national economy. The Council also requests some detailed but important modifications to bring NPF2 into line with other Scottish Government policy. -

Greater Britain: a Useful Category of Historical Analysis?

!"#$%#"&'"(%$()*&+&,-#./0&1$%#23"4&3.&5(-%3"(6$0&+)$04-(-7 +/%83"9-:*&;$<(=&+">(%$2# ?3/"6#*&@8#&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&A#<(#BC&D30E&FGHC&I3E&JC&9+K"EC&FLLL:C&KKE&HJMNHHO P/Q0(-8#=&Q4*&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&+--36($%(3) ?%$Q0#&,AR*&http://www.jstor.org/stable/2650373 +66#--#=*&SGTGUTJGGV&FV*SU Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org AHR Forum Greater Britain: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis? DAVID ARMITAGE THE FIRST "BRITISH" EMPIRE imposed England's rule over a diverse collection of territories, some geographically contiguous, others joined to the metropolis by navigable seas. -

Market Profile Scotland Contents

Market Profile Scotland Contents Overview of Scotland The Seven Cities of Scotland Summary Overview of Scotland Demographics Youth Employment/ Unemployment in Scotland The population of Scotland has increased each year since 2001 and is now at its highest ever. Currently 345,000 young people in National Records of Scotland (NRS) show that the estimated population of Scotland was employment up by 9,000 over the year 5,327,700 in mid-2014. (Sep-Nov 2014) Population change in Scotland is determined by three key elements: Scotland outperforms the UK on youth employment, youth unemployment and youth inactivity rates – • Birth rates higher youth employment rate (56.3% vs. 52.2%), lower youth unemployment rate (16.4% vs. 17.4%) and • Life expectancy lower youth inactivity rate (32.7% vs. 36.8%). • Net migration Of the age groups, those aged 16-24 have the highest unemployment rate - 17,790 young people aged 16- These are, in turn, influenced by a combination of factors, including the relative levels of 24 were on the claimant count in December 2014, a economic prosperity and opportunity, quality of life and the provision of key public services. decrease of 8,830 (33.2%) over the year. The number of people in employment in Scotland has increased by 50,000 over the past year, reaching a record high of 2,612,000 as recent GDP figures show the fastest annual growth since 2007. Overview of Scotland Economy of Scotland Scotland currently has the highest employment rate, lowest unemployment rate and lowest inactivity rate of all four UK nations. -

Turner & Townsend

EEFW/S5/20/COVID/28 ECONOMY, ENERGY AND FAIR WORK COMMITTEE COVID-19 – impact on Scotland’s businesses, workers and economy SUBMISSION FROM TURNER & TOWNSEND 1. Turner & Townsend is an independent global consultancy business, based in the UK, supporting clients with their capital projects and programmes in the real estate, infrastructure and natural resources sectors. We have 110 offices in 45 countries, with Scottish offices, employing over 200 people, located in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen. We have provided consultancy services on a range of key projects across Scotland including Edinburgh Glasgow (rail) Improvement Programme on behalf of Network Rail, the Hydro (The Event Complex Aberdeen) on behalf of Henry Boot Development’s alongside Aberdeen City Council, the Victoria and Albert museum in Dundee on behalf of Dundee Council, Beauly Denny on behalf of SSE, Edinburgh Tram (post settlement agreement) for City of Edinburgh Council and Edinburgh Airport Capital Expansion Programme. Additionally we are currently involved in a number of key infrastructure projects including the A9 road dualling between Perth and Inverness for Transport Scotland, Edinburgh trams to Newhaven extension for City of Edinburgh Council, the Subway Modernisation Programme on behalf of SPT and the key flood defence scheme in Stonehaven on behalf of Aberdeenshire Council. 2. We are submitting evidence to the Committee to inform its work looking at the support that is being made available to businesses and workers and other measures aimed at mitigating the impact of COVID-19. We want to make the Committee aware of two issues: a. the first in regard to restarting those paused capital construction projects designated within the Critical National Infrastructure (CNI) sectors but deemed non-essential to the national COVID-19 effort and; b. -

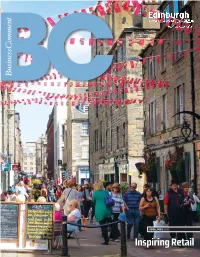

Inspiring Retail

APRIL/MAY 2015 Inspiring Retail February/March 2015 BC 3 Introduction / contents 03 Launch of Inspiring Retail Group 04 10 Successful Festival Trading for Retailers 05 Edinburgh Chamber Importance of the Retail Industry 07 celebrates success at Business Mentoring Scotland 08 our annual Awards Chamber Benefits 09 Edinburgh Chamber Awards 10|13 60 Seconds 23 05 28 Business Stream Appointment 24 Successful Festival An interview with Getting into Retail Management 25 Trading for Retailers Gordon Drummond, Bohemia - A part of Edinburgh’s Mix 26 General Manager at Harvey Nichols A Passion for Retailing 28 Feature: Health and Wellbeing 30|38 Partners in Enterprise 39 Ask the Expert/New Members 40 Inspiring Retail Getting Started 41 Be The Best/Get with IT 42 Retail is business critical to Christmas is one of the latest examples, and in this issue we learn how important that Going International 43 a healthy and diverse Capital event has been in helping retailers at their City. most vital time of year. Chamber Training 44 The retail sector is a major contributor to More than 300 people attended our glittering In the Spotlight 45 our economy through the jobs created, 2015 Business Awards at the Sheraton Grand investment it brings, and a significant driver Hotel. The awards are designed to celebrate Feature: Property 46|51 the enterprise, creativity and excellence of of football both domestically and to meet Inspiring Connections 52|53 the needs of growing visitor numbers. In this our members, so it was entirely appropriate issue we launch our Inspiring Retail Group that the evening was our biggest and best Movers & Shakers 54 highlighting the sector as a strategic priority to date. -

Broadly Speaking : Scots Language and British Imperialism

BROADLY SPEAKING: SCOTS LANGUAGE AND BRITISH IMPERIALISM Sean Murphy A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2017 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11047 This item is protected by original copyright Sean Murphy, ‘Broadly Speaking. Scots language and British imperialism.’ Abstract This thesis offers a three-pronged perspective on the historical interconnections between Lowland Scots language(s) and British imperialism. Through analyses of the manifestation of Scots linguistic varieties outwith Scotland during the nineteenth century, alongside Scottish concerns for maintaining the socio-linguistic “propriety” and literary “standards” of “English,” this discussion argues that certain elements within Lowland language were employed in projecting a sentimental-yet celebratory conception of Scottish imperial prestige. Part I directly engages with nineteenth-century “diasporic” articulations of Lowland Scots forms, focusing on a triumphal, ceremonial vocalisation of Scottish shibboleths, termed “verbal tartanry.” Much like physical emblems of nineteenth-century Scottish iconography, it is suggested that a verbal tartanry served to accentuate Scots distinction within a broader British framework, tied to a wider imperial superiorism. Parts II and III look to the origins of this verbal tartanry. Part II turns back to mid eighteenth-century Scottish linguistic concerns, suggesting the emergence of a proto-typical verbal tartanry through earlier anxieties to ascertain “correct” English “standards,” and the parallel drive to perceive, prohibit, and prescribe Scottish linguistic usage. It is argued that later eighteenth-century Scottish philological priorities for the roots and “purity” of Lowland Scots forms – linked to “ancient” literature and “racially”-loaded origin myths – led to an encouraged “uncovering” of hallowed linguistic traits.