Cryptography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Cryptography

Basic cryptography • How cryptography works... • Symmetric cryptography... • Public key cryptography... • Online Resources... • Printed Resources... I VP R 1 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz How cryptography works • Plaintext • Ciphertext • Cryptographic algorithm • Key Decryption Key Algorithm Plaintext Ciphertext Encryption I VP R 2 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Simple cryptosystem ... ! ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ! DEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABC • Caesar Cipher • Simple substitution cipher • ROT-13 • rotate by half the alphabet • A => N B => O I VP R 3 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys cryptosystems … • keys and keyspace ... • secret-key and public-key ... • key management ... • strength of key systems ... I VP R 4 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys and keyspace … • ROT: key is N • Brute force: 25 values of N • IDEA (international data encryption algorithm) in PGP: 2128 numeric keys • 1 billion keys / sec ==> >10,781,000,000,000,000,000,000 years I VP R 5 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Symmetric cryptography • DES • Triple DES, DESX, GDES, RDES • RC2, RC4, RC5 • IDEA Key • Blowfish Plaintext Encryption Ciphertext Decryption Plaintext Sender Recipient I VP R 6 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz DES • Data Encryption Standard • US NIST (‘70s) • 56-bit key • Good then • Not enough now (cracked June 1997) • Discrete blocks of 64 bits • Often w/ CBC (cipherblock chaining) • Each blocks encr. depends on contents of previous => detect missing block I VP R 7 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Triple DES, DESX, -

On the Randomness Complexity of Interactive Proofs and Statistical Zero-Knowledge Proofs*

On the Randomness Complexity of Interactive Proofs and Statistical Zero-Knowledge Proofs* Benny Applebaum† Eyal Golombek* Abstract We study the randomness complexity of interactive proofs and zero-knowledge proofs. In particular, we ask whether it is possible to reduce the randomness complexity, R, of the verifier to be comparable with the number of bits, CV , that the verifier sends during the interaction. We show that such randomness sparsification is possible in several settings. Specifically, unconditional sparsification can be obtained in the non-uniform setting (where the verifier is modelled as a circuit), and in the uniform setting where the parties have access to a (reusable) common-random-string (CRS). We further show that constant-round uniform protocols can be sparsified without a CRS under a plausible worst-case complexity-theoretic assumption that was used previously in the context of derandomization. All the above sparsification results preserve statistical-zero knowledge provided that this property holds against a cheating verifier. We further show that randomness sparsification can be applied to honest-verifier statistical zero-knowledge (HVSZK) proofs at the expense of increasing the communica- tion from the prover by R−F bits, or, in the case of honest-verifier perfect zero-knowledge (HVPZK) by slowing down the simulation by a factor of 2R−F . Here F is a new measure of accessible bit complexity of an HVZK proof system that ranges from 0 to R, where a maximal grade of R is achieved when zero- knowledge holds against a “semi-malicious” verifier that maliciously selects its random tape and then plays honestly. -

Classical Encryption Techniques

CPE 542: CRYPTOGRAPHY & NETWORK SECURITY Chapter 2: Classical Encryption Techniques Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Computer Engineering Department Jordan University of Science and Technology Jordan Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 Introduction Basic Terminology • plaintext - the original message • ciphertext - the coded message • key - information used in encryption/decryption, and known only to sender/receiver • encipher (encrypt) - converting plaintext to ciphertext using key • decipher (decrypt) - recovering ciphertext from plaintext using key • cryptography - study of encryption principles/methods/designs • cryptanalysis (code breaking) - the study of principles/ methods of deciphering ciphertext Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 1 Cryptographic Systems Cryptographic Systems are categorized according to: 1. The operation used in transferring plaintext to ciphertext: • Substitution: each element in the plaintext is mapped into another element • Transposition: the elements in the plaintext are re-arranged. 2. The number of keys used: • Symmetric (private- key) : both the sender and receiver use the same key • Asymmetric (public-key) : sender and receiver use different key 3. The way the plaintext is processed : • Block cipher : inputs are processed one block at a time, producing a corresponding output block. • Stream cipher: inputs are processed continuously, producing one element at a time (bit, Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 Cryptographic Systems Symmetric Encryption Model Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 2 Cryptographic Systems Requirements • two requirements for secure use of symmetric encryption: 1. a strong encryption algorithm 2. a secret key known only to sender / receiver •Y = Ek(X), where X: the plaintext, Y: the ciphertext •X = Dk(Y) • assume encryption algorithm is known •implies a secure channel to distribute key Dr. -

Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Lecture 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard Lecture Notes on “Computer and Network Security” by Avi Kak ([email protected]) January 26, 2021 3:43pm ©2021 Avinash Kak, Purdue University Goals: To introduce the notion of a block cipher in the modern context. To talk about the infeasibility of ideal block ciphers To introduce the notion of the Feistel Cipher Structure To go over DES, the Data Encryption Standard To illustrate important DES steps with Python and Perl code CONTENTS Section Title Page 3.1 Ideal Block Cipher 3 3.1.1 Size of the Encryption Key for the Ideal Block Cipher 6 3.2 The Feistel Structure for Block Ciphers 7 3.2.1 Mathematical Description of Each Round in the 10 Feistel Structure 3.2.2 Decryption in Ciphers Based on the Feistel Structure 12 3.3 DES: The Data Encryption Standard 16 3.3.1 One Round of Processing in DES 18 3.3.2 The S-Box for the Substitution Step in Each Round 22 3.3.3 The Substitution Tables 26 3.3.4 The P-Box Permutation in the Feistel Function 33 3.3.5 The DES Key Schedule: Generating the Round Keys 35 3.3.6 Initial Permutation of the Encryption Key 38 3.3.7 Contraction-Permutation that Generates the 48-Bit 42 Round Key from the 56-Bit Key 3.4 What Makes DES a Strong Cipher (to the 46 Extent It is a Strong Cipher) 3.5 Homework Problems 48 2 Computer and Network Security by Avi Kak Lecture 3 Back to TOC 3.1 IDEAL BLOCK CIPHER In a modern block cipher (but still using a classical encryption method), we replace a block of N bits from the plaintext with a block of N bits from the ciphertext. -

A Secure Authentication System- Using Enhanced One Time Pad Technique

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.11 No.2, February 2011 11 A Secure Authentication System- Using Enhanced One Time Pad Technique Raman Kumar1, Roma Jindal 2, Abhinav Gupta3, Sagar Bhalla4 and Harshit Arora 5 1,2,3,4,5 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, 1,2,3,4,5 D A V Institute of Engineering and Technology, Jalandhar, Punjab, India. Summary the various weaknesses associated with a password have With the upcoming technologies available for hacking, there is a come to surface. It is always possible for people other than need to provide users with a secure environment that protect their the authenticated user to posses its knowledge at the same resources against unauthorized access by enforcing control time. Password thefts can and do happen on a regular basis, mechanisms. To counteract the increasing threat, enhanced one so there is a need to protect them. Rather than using some time pad technique has been introduced. It generally random set of alphabets and special characters as the encapsulates the enhanced one time pad based protocol and provides client a completely unique and secured authentication passwords we need something new and something tool to work on. This paper however proposes a hypothesis unconventional to ensure safety. At the same time we need regarding the use of enhanced one time pad based protocol and is to make sure that it is easy to be remembered by you as a comprehensive study on the subject of using enhanced one time well as difficult enough to be hacked by someone else. -

1 Perfect Secrecy of the One-Time Pad

1 Perfect secrecy of the one-time pad In this section, we make more a more precise analysis of the security of the one-time pad. First, we need to define conditional probability. Let’s consider an example. We know that if it rains Saturday, then there is a reasonable chance that it will rain on Sunday. To make this more precise, we want to compute the probability that it rains on Sunday, given that it rains on Saturday. So we restrict our attention to only those situations where it rains on Saturday and count how often this happens over several years. Then we count how often it rains on both Saturday and Sunday. The ratio gives an estimate of the desired probability. If we call A the event that it rains on Saturday and B the event that it rains on Sunday, then the intersection A ∩ B is when it rains on both days. The conditional probability of A given B is defined to be P (A ∩ B) P (B | A)= , P (A) where P (A) denotes the probability of the event A. This formula can be used to define the conditional probability of one event given another for any two events A and B that have probabilities (we implicitly assume throughout this discussion that any probability that occurs in a denominator has nonzero probability). Events A and B are independent if P (A ∩ B)= P (A) P (B). For example, if Alice flips a fair coin, let A be the event that the coin ends up Heads. If Bob rolls a fair six-sided die, let B be the event that he rolls a 3. -

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, Newdes, RC2, and TEA

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA John Kelsey Bruce Schneier David Wagner Counterpane Systems U.C. Berkeley kelsey,schneier @counterpane.com [email protected] f g Abstract. We present new related-key attacks on the block ciphers 3- WAY, Biham-DES, CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA. Differen- tial related-key attacks allow both keys and plaintexts to be chosen with specific differences [KSW96]. Our attacks build on the original work, showing how to adapt the general attack to deal with the difficulties of the individual algorithms. We also give specific design principles to protect against these attacks. 1 Introduction Related-key cryptanalysis assumes that the attacker learns the encryption of certain plaintexts not only under the original (unknown) key K, but also under some derived keys K0 = f(K). In a chosen-related-key attack, the attacker specifies how the key is to be changed; known-related-key attacks are those where the key difference is known, but cannot be chosen by the attacker. We emphasize that the attacker knows or chooses the relationship between keys, not the actual key values. These techniques have been developed in [Knu93b, Bih94, KSW96]. Related-key cryptanalysis is a practical attack on key-exchange protocols that do not guarantee key-integrity|an attacker may be able to flip bits in the key without knowing the key|and key-update protocols that update keys using a known function: e.g., K, K + 1, K + 2, etc. Related-key attacks were also used against rotor machines: operators sometimes set rotors incorrectly. -

Oacerts: Oblivious Attribute Certificates

OACerts: Oblivious Attribute Certificates Jiangtao Li and Ninghui Li CERIAS and Department of Computer Science, Purdue University 250 N. University Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907 {jtli,ninghui}@cs.purdue.edu Abstract. We propose Oblivious Attribute Certificates (OACerts), an attribute certificate scheme in which a certificate holder can select which attributes to use and how to use them. In particular, a user can use attribute values stored in an OACert obliviously, i.e., the user obtains a service if and only if the attribute values satisfy the policy of the service provider, yet the service provider learns nothing about these attribute values. This way, the service provider’s access con- trol policy is enforced in an oblivious fashion. To enable the oblivious access control using OACerts, we propose a new cryp- tographic primitive called Oblivious Commitment-Based Envelope (OCBE). In an OCBE scheme, Bob has an attribute value committed to Alice and Alice runs a protocol with Bob to send an envelope (encrypted message) to Bob such that: (1) Bob can open the envelope if and only if his committed attribute value sat- isfies a predicate chosen by Alice, (2) Alice learns nothing about Bob’s attribute value. We develop provably secure and efficient OCBE protocols for the Pedersen commitment scheme and predicates such as =, ≥, ≤, >, <, 6= as well as logical combinations of them. 1 Introduction In Trust Management and certificate-based access control Systems [3, 40, 19, 11, 34, 33], access control decisions are based on attributes of requesters, which are estab- lished by digitally signed certificates. Each certificate associates a public key with the key holder’s identity and/or attributes such as employer, group membership, credit card information, birth-date, citizenship, and so on. -

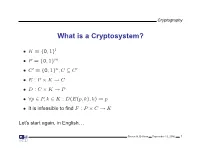

What Is a Cryptosystem?

Cryptography What is a Cryptosystem? • K = {0, 1}l • P = {0, 1}m • C′ = {0, 1}n,C ⊆ C′ • E : P × K → C • D : C × K → P • ∀p ∈ P, k ∈ K : D(E(p, k), k) = p • It is infeasible to find F : P × C → K Let’s start again, in English. Steven M. Bellovin September 13, 2006 1 Cryptography What is a Cryptosystem? A cryptosystem is pair of algorithms that take a key and convert plaintext to ciphertext and back. Plaintext is what you want to protect; ciphertext should appear to be random gibberish. The design and analysis of today’s cryptographic algorithms is highly mathematical. Do not try to design your own algorithms. Steven M. Bellovin September 13, 2006 2 Cryptography A Tiny Bit of History • Encryption goes back thousands of years • Classical ciphers encrypted letters (and perhaps digits), and yielded all sorts of bizarre outputs. • The advent of military telegraphy led to ciphers that produced only letters. Steven M. Bellovin September 13, 2006 3 Cryptography Codes vs. Ciphers • Ciphers operate syntactically, on letters or groups of letters: A → D, B → E, etc. • Codes operate semantically, on words, phrases, or sentences, per this 1910 codebook Steven M. Bellovin September 13, 2006 4 Cryptography A 1910 Commercial Codebook Steven M. Bellovin September 13, 2006 5 Cryptography Commercial Telegraph Codes • Most were aimed at economy • Secrecy from casual snoopers was a useful side-effect, but not the primary motivation • That said, a few such codes were intended for secrecy; I have some in my collection, including one intended for union use Steven M. -

Cryptography in Modern World

Cryptography in Modern World Julius O. Olwenyi, Aby Tino Thomas, Ayad Barsoum* St. Mary’s University, San Antonio, TX (USA) Emails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract — Cryptography and Encryption have been where a letter in plaintext is simply shifted 3 places down used for secure communication. In the modern world, the alphabet [4,5]. cryptography is a very important tool for protecting information in computer systems. With the invention ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ of the World Wide Web or Internet, computer systems are highly interconnected and accessible from DEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABC any part of the world. As more systems get interconnected, more threat actors try to gain access The ciphertext of the plaintext “CRYPTOGRAPHY” will to critical information stored on the network. It is the be “FUBSWRJUASLB” in a Caesar cipher. responsibility of data owners or organizations to keep More recent derivative of Caesar cipher is Rot13 this data securely and encryption is the main tool used which shifts 13 places down the alphabet instead of 3. to secure information. In this paper, we will focus on Rot13 was not all about data protection but it was used on different techniques and its modern application of online forums where members could share inappropriate cryptography. language or nasty jokes without necessarily being Keywords: Cryptography, Encryption, Decryption, Data offensive as it will take those interested in those “jokes’ security, Hybrid Encryption to shift characters 13 spaces to read the message and if not interested you do not need to go through the hassle of converting the cipher. I. INTRODUCTION In the 16th century, the French cryptographer Back in the days, cryptography was not all about Blaise de Vigenere [4,5], developed the first hiding messages or secret communication, but in ancient polyalphabetic substitution basically based on Caesar Egypt, where it began; it was carved into the walls of cipher, but more difficult to crack the cipher text. -

A Covert Encryption Method for Applications in Electronic Data Interchange

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Articles School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2009-01-01 A Covert Encryption Method for Applications in Electronic Data Interchange Jonathan Blackledge Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Dmitry Dubovitskiy Oxford Recognition Limited, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/engscheleart2 Part of the Digital Communications and Networking Commons, Numerical Analysis and Computation Commons, and the Software Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Blackledge, J., Dubovitskiy, D.: A Covert Encryption Method for Applications in Electronic Data Interchange. ISAST Journal on Electronics and Signal Processing, vol: 4, issue: 1, pages: 107 -128, 2009. doi:10.21427/D7RS67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License A Covert Encryption Method for Applications in Electronic Data Interchange Jonathan M Blackledge, Fellow, IET, Fellow, BCS and Dmitry A Dubovitskiy, Member IET Abstract— A principal weakness of all encryption systems is to make sure that the ciphertext is relatively strong (but not that the output data can be ‘seen’ to be encrypted. In other too strong!) and that the information extracted is of good words, encrypted data provides a ‘flag’ on the potential value quality in terms of providing the attacker with ‘intelligence’ of the information that has been encrypted. -

A Practical Implementation of a One-Time Pad Cryptosystem

Jeff Connelly CPE 456 June 11, 2008 A Practical Implementation of a One-time Pad Cryptosystem 0.1 Abstract How to securely transmit messages between two people has been a problem for centuries. The first ciphers of antiquity used laughably short keys and insecure algorithms easily broken with today’s computational power. This pattern has repeated throughout history, until the invention of the one-time pad in 1917, the world’s first provably unbreakable cryptosystem. However, the public generally does not use the one-time pad for encrypting their communication, despite the assurance of confidentiality, because of practical reasons. This paper presents an implementation of a practical one-time pad cryptosystem for use between two trusted individuals, that have met previously but wish to securely communicate over email after their departure. The system includes the generation of a one-time pad using a custom-built hardware TRNG as well as software to easily send and receive encrypted messages over email. This implementation combines guaranteed confidentiality with practicality. All of the work discussed here is available at http://imotp.sourceforge.net/. 1 Contents 0.1 Abstract.......................................... 1 1 Introduction 3 2 Implementation 3 2.1 RelatedWork....................................... 3 2.2 Description ........................................ 3 3 Generating Randomness 4 3.1 Inadequacy of Pseudo-random Number Generation . 4 3.2 TrulyRandomData .................................... 5 4 Software 6 4.1 Acquiring Audio . 6 4.1.1 Interference..................................... 6 4.2 MeasuringEntropy................................... 6 4.3 EntropyExtraction................................ ..... 7 4.3.1 De-skewing ..................................... 7 4.3.2 Mixing........................................ 7 5 Exchanging Pads 8 5.1 Merkle Channels . 8 5.2 Local Pad Security .