Interview with Frederick C. Smith FM-V-L-2010-015 Interview # 1: April 2, 2010 Interviewer: Mark R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Ocm13697396-1891.Pdf

LIBRARY OF THE MASSACHUSETTS AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE SOURCE. ..a:v_?-t M. ^. C. coiircTioN Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/index1893univ ^t PA RKEIR c^ \A/OOD, ^i'-<- BOSTON, MASS. TlIK IIEADdUAKTl'KS FOI; K\i: inTIll Ni ', I'DR FARM, (tARDEN, """ LAWN. Ground Oyster nniTT OnDDI TTO Excelsior Ground Beef Scraps, Excelsior XnV Havens' Con- Shells, Dole's Desiccated Fish, Rust's 1 UULlKl OUl 1 LIlO dition Powders, Rust's Egg Producer. WHOLESALE AND RETAIL DEALERS IN VEGET^tBI^E— « r r n Q — F1.0AVER Karrx^ing Tools, OttUO Wooden Ware, PLANTS, VINES, TREES, SHRUBS. PARKER & WOOD, 49 North Market Street, Boston, Mass. A.W arded Stiver MedctZ of Honor' for i^ BKST PHOTOGRAPHS ^ MADE IN WESrERN MASSAGHaSErrs. Tl^is stiould induce all ^t^i\o desire tY[e best to visit our Studio. SPECIAL RATES TO COLLEGE CLASSES. 141 Main St., opposite Memorial Hall, ^ Main St., opposite Brooks House, UP ONE FLIGHT, 4 UP ONE FLIGHT, NORTHAMPTON, MASS. ^ BRATTLEBORO, VT. Federal St., near Mansion House, Ground Floor, . GREENFIELD, MASS. GEO. E. COLE & CO., PHOTOGRAPHERS. ONLY FIRST-CLASS WORK DONE, AT MODERATE PRICES. OI^A.SS WORJ^: A. SPECIALTY. 143 MAIN STREET, NORTHAMPTON, MASS. John ]V[uiiL:En, DEALER IN Provisions, ^^ Meat, pish, Oysteps, FRUIT, GANIE, Etc. Cjhoige: L^ine: of Cannejd Coods. pal(r\er's E\oq\{, AlVItiERST, MASS /T\assa(;t7us(?tt5 /^(^rieijltijral ^olli?^<^, A RARE CHANCE for young men to obtain a thorough practical education. The cost reduced to a minimum. -

Patti Smith & Robert Mapplethorpe Both Became Art-World Legends and ’70S Icons of Radical Downtown Bohemia

They WERE NEW YORK BEFORE NEW YORK KNEW what to do WITH THEM. They WERE LOVERS, BEST FRIENDS, FELLOW SURVIVORS. PATTI SMITH & ROBERT MAppLETHORPE BOTH BECAME ART-WORLD LEGENDS and ’70S ICONS OF RADICAL DOWNTOWN BOHEMIA. Now SMITH FINALLY OPENS UP about THEIR DAYS together, LIVING at the CHELSEA HOTEL, BUYING ART SUppLIES BEFORE FOOD, MIXING with WARHOL SUPERSTARS and FUTURE ROCK GODS, and DOING WHATEVER they HAD to DO JUST to STAY TOGETHER By CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN THIS SPREAD: PATTI SMITH AND ROBERT MAppLETHOrpE IN NEW YORK, 1970. PHOTOS: NORMAN SEEFF. In 1967, Patti Smith moved to New York City from and a pot of water and I keep diluting it, because it’s certainly hasn’t changed. When I was a kid, I South Jersey, and the rest is epic history. There are not even the coffee, it’s the habit. wore dungarees and little boatneck shirts and the photographs, the iconic made-for-record-cover BOLLEN: That’s my problem. I really don’t braids. I dressed like that throughout the ’50s, to black-and-whites shot by Smith’s lover, soul mate, and smoke cigarettes that much except when I write. the horror of my parents and teachers. co-conspirator in survival, Robert Mapplethorpe. But when I write, I smoke. It’s bad, but I’m scared BOLLEN: Most people take a long time to find Then there are the photographs taken of them that if I break the habit, I won’t be able to write. themselves—if they ever do. How did you catch together, both with wild hair and cloaked in home- SMITH: It’s part of your process. -

Business [Ncrease Quarantine Is Off the New

f The Clinton Republican. 53d Year—No. 40. ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1908. Whole No. 2744. VARIOUS TOPICS. COUNTY POMONA. POMONA NOTICE. BUSINESS_ [NCREASE What did you set? QUARANTINE IS OFF Large Attendance at Meeting With THE NEW CO,OFFICERS Clinton County Pomona Grange, No. OUR TIMBER SUPPLY • • • Olive Grange. 25, will meet with Bengal Grange on Christmas is just 365 days off, now Wednesday, January 6, 1909. Is Shown in St. Johns for the for business. On Michigan Cattle in All Will Soon Assume Duties at All fourth degree members invited. Wasteful Methods Destroy a • • • Clinton County Pomona met with Grange called In fifth degree at 10:30; Past Year. The Republican wishes its many But Olive Grange Wednesday, December Court House. called in fourth degree at 11 am. Great Amount. readers a very Merry Christmas and a 16, 1908. The attendance was very Regular order of business: Reports happy New Year. large. Some estimated the crowd at of subordinate granges. FEW - EXCEPTION^ * • • FIVE COUNTIES. 200. The members of Olive grange FEWER MARRIAGES When is the best time to trim fruit INTELLIGENT CARE The editor of the Herald suffered a have been painting and repairing and trees, grape vines, etc.?—Levi Green papering the inalde of their hall so it wood. slight accident this week. He was Just Foot and Mouth Disease 8eems to Be And Fewer Divorces the ‘Past Year— Can Be Found —Increases From $400 stepping into his new $2,000 automo looks very neat and attractive. Nine Which is the more profitable in a Would Increase Growth and Utilize Sheriff Keeney Moving to to $1,600 Up to Last Week bile when three bed slats broke and he Entirely Wiped Out granges were represented and encour neighborhood, a milk shipping station Much That Now Goes was awakened. -

1929 Yearbook

~ THI: SALlrM LABEL CO. Page Three cr.-:6·9 rVOt..$ N To Miss Ethel Beardmore, a teacher who has guided the Senior class successfully through a year of accomplishment, who has greeted them from day to day in a friendly attitude, who has worked earnestly with them in an effort to lead them· on and make them an outstanding class, we" the class of 29, sincerely. dedicate this twenty-third issue of the Quaker Annual. : . Page Four Page Five In memory of our beloved classmate,· Ruth Ledora Bentley, who passed from our midst, September 17, 1928. Page Six Page Seven With the purpose of submitting to you an account of the past year's activities, we, the Quaker staff present to you this twenty third "Quaker" annual. In this issue we have tried to give you such a summary of these past activities of the Seniors as will bring them back to you. We have endeavored to construct the an nual around a single theme, that of Quaker life and custom. This theme is expressed in ·~ / AD. torwo~d Page Eight Dedication ______________________ Page 4 In Memoriam ___________________ Page 6 Foreword _______________________ Page 8 Administration __________________ Page 11 Faculty ____________________ Page 15 Seniors _____________________ Page 19 Juniors _____________________ Page 35 Sophoinores ________________ Page 39 Freshinen --------~---------Page 43 Athletics _______________________ Page 47 Cheerleaders ________________ Page 49 Reilly Stadiuin Page 50 Football ____________________ Page 51 · Boys Basketball _____________ Page 53 Girls Basketball _____________ Page -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8 Music Boo-Hooray is proud to present our eighth antiquarian catalog, dedicated to music artifacts and ephemera. Included in the catalog is unique artwork by Tomata Du Plenty of The Screamers, several incredible items documenting music fan culture including handmade sleeves for jazz 45s, and rare paste-ups from reggae’s entrance into North America. Readers will also find the handmade press kit for the early Björk band, KUKL, several incredible hip-hop posters, and much more. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Ben Papaleo, Evan, and Daylon. Layout by Evan. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Table of Contents 31. [Patti Smith] Hey Joe (Version) b/w Piss Factory .................. -

Albany Student Press 1981-05-01

11111 i-l 11111I j1111 M 111111 mi 11 II 111111iI 11iI 11II1111 I I I 11 II I I I II I I II II I I i II Trackmen Romp page 18 April 28, 1981 Danes Sweep Colgate as Esposito Gets Record by Bob Bellaflore sixth when Rhodes (2-3) doubled to to bunt him over, but Masseroni's As a rule, Division III teams are the right field corner. Designated throw pulled Rowlands off the bag not supposed to beat Division I runner Steve Shucker went to third and both men were on. Kratley Cocks' New Contract is Recommended teams. on Colgate hurlcr Joe Spofford's struck out on three pitches, but Staats singled to right and Nuti by Belli Sexer So much for rules. wild pitch, and came in on Lynch's portant llial he be shown .support. scored. positive recommendation he looks The Albany State varsity baseball line single to center. Faeully and students afire over Marlin said lhai on a personal all accounts one of Ihe besl teachers team won its eighth game in a row Colgate's runs were all unearned. Colgate went up 2-1 in the next Vice President for Academic Af for "a balance of leaching and in ihc university should be sum level he had "mixed emotions" and scholarship and university service." and increased their already im They got one in the fifth when John inning. Tortorello went deep in the fairs David Martin's recommenda "severe reservations" about his marily canned" for not publishing pressive record to 10-1 by sweeping Kratley reached on a force play, hole at shortstop to field Dave tion thai Political Science Professor Martin's firs! recommendation enough, he said. -

New York City's Societal Influence on the Punk

Department of Humanities, Northumbria University Honours Dissertation New York City’s Societal Influence on the Punk Movement, 1975-1979 Gavin Keen BA Hons History 2016 This dissertation has been made available on condition that anyone who consults it recognises that its copyright rests with its author and that quotation from the thesis and/or the use of information derived from it must be acknowledged. © Gavin Keen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) History !1 Contents Introduction: ‘Fear City’ and the Creation of a Scene 3 Chapter 1: ‘Trying to turn a trick’:The NYC Sex Industry and its Influence on Punk 8 Chapter 2: ‘All I see is little dots’: The NYC Drug Industry and its Influence on Punk 15 Chapter 3: ‘Yuck! She’s too much’: Gender and Sexuality in NYC and Punk 22 Conclusion: ‘New York City Really Has It All’: Punk as a Social Commentary 33 Appendices 37 Bibliography 43 !2 Introduction ‘Fear City’ and the Creation of a Scene New York’s economic situation in the mid 1970s saw unprecedented levels of austerity imposed upon the city and, as a result, contributed to the creation of what the historian Dominic Sandbrook described as ‘a terrifying urban Hades’.1 Swathes of New Yorkers were riled by the closure of libraries, hospitals and fire stations and had their anger compounded by subway fare hikes, the abolition of free public college education and severe cuts to public service employment; a total of sixty three thousand public servants, ranging from teachers to police officers, were put out of work.2 The drastic economic measures implemented by Mayor Abraham Beame as part of the conditions of New York’s federal financial bail out contributed significantly to a rise in crime and societal dysfunction across the city. -

FY17 Annual Report View Report

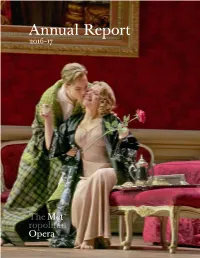

Annual Report 2016–17 1 2 4 Introduction 6 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 3 Introduction In the 2016–17 season, the Metropolitan Opera continued to present outstanding grand opera, featuring the world’s finest artists, while maintaining balanced financial results—the third year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and also included five other new stagings, as well as 20 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 11th year, with ten broadcasts reaching approximately 2.3 million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (Live in HD and box office) totaled $111 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All six new productions in the 2016–17 season were the work of distinguished directors who had previous success at the Met. The compelling Opening Night new production of Tristan und Isolde was directed by Mariusz Treliński, who made his Met debut in 2015 with the double bill of Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta and Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle. French-Lebanese director Pierre Audi brought his distinctive vision to Rossini’s final operatic masterpiece Guillaume Tell, following his earlier staging of Verdi’s Attila in 2010. Robert Carsen, who first worked at the Met in 1997 on his popular production of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, directed a riveting new Der Rosenkavalier, the company’s first new staging of Strauss’s grand comedy since 1969. -

Fred Stair Elected Student Body President

l'iii«*riii«\v«"i- L«M-iur«'s Phi Kola Kappa IBmIk Tuesday Gflfje Batottosoman Announced ALENDA LUX U B I ORTA LIBERTAS ZS28 VOL. XXV DAVIDSON COLLEGE, DAVIDSON, N. C, WEDNESDAY, MAR. 16, 1938 NO. 26 Fred Stair Elected Student Body President Scholarship Fraternity Maestro Freshman Franchise Is Fred Stair Spencer) Is Extends Bitls To Seven Passed By Large Margin Chosen On Gailey, '37, Dorsett, Lafferty, Amendment Will Go Into Ef- First Vote Horine,Kiesewetter, Holt, Council Calls *" * fect Second Semester of Fernininily To and Cates Bidden »# f 3r ■Ell Next Session I'ti-il Stair, of Knoxville, was The local chapter of Phi Be- Halt In Vote By ihc overwhelming majority of Be HonoredIn elected president of the Dav- idson College on ta Kappa, national honorary .iju io (iO, the amenclmeni t.> the student body yesterday fraternity, has ex- Student Body Elections Run Student Bod\ Constitution pro- the second ballot scholarship New Magazine morning. Spencer tended bids to one alumnus, Over Due to Political viding for the freshman ftfinchfac Sam was J. Complications made iir-\ vice president on M. Galley,'37, and members of was passyjj in ilir \ « ttiiij.- InI<1 last "Chicken" Issue of Scripts 'n class of '38, |. Saturday morning, the first ballot Monday. Elec- the K. Dorsctt. \iter new first and sec- Pranks Will Appear Be- tion of MVi'titl L E. Horine, the This atiu'iidmcnt, known as Sec- vice president M. Lafferty, F. ond vice-presidents of the stu- fore Holidays and had Kiesewetter, K. Holt, Hi in (i, wii-. first proposed in \\h- secretary-treasurer W. -

H. W. Maglidt Conducts Wage Survey of Albuquerque, Publishes

AND IA ULLETIN ....Vol. IV. No. 8 SANDIA CORPORATION, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO . April!!, 1952 C. W. Carnahan Is H. W. Maglidt Conducts Wage Survey Named Fellow of 181 Men And Women from 37 States Engineering Group Join Sandia Corporation In March Of Albuquerque, Publishes Findings "For contributions to frequency Eighty-six men and women from uates : Brown University: Te::cas A H. W. Maglidt,. a Sandia Corpora• student in the Department of Eco• modulation, television, and electronic 36 states other than New Mexico & M, Kansas State, Umvers,1ty of tion employee who is doing graduate nomics of the University. Mr. Mag• · systems engineering ..." So read the came to Albuquerque during March Michigan, Col~r\).do. A & M, Ala• work at the University of New Mex• lidt undertook this ambitious project citation that went with the Fellow to work for Sandia Corporation. In bama Tech, Umvers1ty of New Mex• ico, has played a major part in the in ·connection with a graduate course addition to these folks, 95 people ico, Washington State. conducting compiling and writing of in business research. from New Mexico joined Sandia University of Washington, ~outh "He bore . the responsibility of planning and organizing the p-roject, during the month. Dakota State Colle?e, ':"estmn;ster setting up the job descriptions, forms Further swelling the polJ'ulation of ~ollege, ~enver Umverslt~, Umver- · d · th 31 day period s1ty of Anzona, St. Josephs College, and instructions, training the inter• t h e c1ty unng e - U . · f Okl h T T h viewers and soliciting the coopera• were the 183 children included in mverslty 0 • ~ oma, exas ec · h 148 f T f th up Boston Umvers1ty, College of St. -

The Early History of the Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project.Pdf

PPEr’DIX A-2 The Early History of the Michigan Memorial - Phoenix Project with Special Reference to the Social Sciences and Humanities prepared by: Nicholas H. Steneck, Director Collegiate Tiistitute for Values and Science for the: Michigan Memorial - Phoenix Project Review Committee September 1987 Working draft for committee use: may not be duplicated or quoted without permission of the author Table of Contents 1 Institutionalizing the Idea 1 2 Physicians and Physicists 4 3 From Proposal to Project 6 4 Fostering the Social Sciences and Humanities 9 5 Conclusions, Observations, and Recommendations 14 Early History of the MMPP N.H.Steneck Oh, bird of portent, symbol for today, Rekindle vision in despairing eyes; Let them see stars again, and seeing, say: Tomorrow’s children will be free and wise; And they will march again, and march as one, The road from nadir to the farthest sun.1 The Early History of the Michigan Memorial - Phoenix Project with Special Reference to the Social Sciences and Humanities The havoc wrought by wars invariably leaves heavy burdens on the consciences of the survivors. At the outset, wars have their rational justifications. In the aftermath of years of fighting, death, and destruction, justifications can loose their initial clarity. Did those who died do so in vein? War memorials are a way of ensuring that they did not. Built allegedly as monuments to the wounded and dead, they serve to reassure the living of the morality of events that on the surface seem to transgress all laws of morality. In the years immediately following World War II, many university communities in the U.S.