CMU 18-447 Introduction to Computer Architecture, Spring 2014 HW 2: ISA Tradeoffs, Microprogramming and Pipelining 1 LC-3B Micro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PIPELINING and ASSOCIATED TIMING ISSUES Introduction: While

PIPELINING AND ASSOCIATED TIMING ISSUES Introduction: While studying sequential circuits, we studied about Latches and Flip Flops. While Latches formed the heart of a Flip Flop, we have explored the use of Flip Flops in applications like counters, shift registers, sequence detectors, sequence generators and design of Finite State machines. Another important application of latches and flip flops is in pipelining combinational/algebraic operation. To understand what is pipelining consider the following example. Let us take a simple calculation which has three operations to be performed viz. 1. add a and b to get (a+b), 2. get magnitude of (a+b) and 3. evaluate log |(a + b)|. Each operation would consume a finite period of time. Let us assume that each operation consumes 40 nsec., 35 nsec. and 60 nsec. respectively. The process can be represented pictorially as in Fig. 1. Consider a situation when we need to carry this out for a set of 100 such pairs. In a normal course when we do it one by one it would take a total of 100 * 135 = 13,500 nsec. We can however reduce this time by the realization that the whole process is a sequential process. Let the values to be evaluated be a1 to a100 and the corresponding values to be added be b1 to b100. Since the operations are sequential, we can first evaluate (a1 + b1) while the value |(a1 + b1)| is being evaluated the unit evaluating the sum is dormant and we can use it to evaluate (a2 + b2) giving us both |(a1 + b1)| and (a2 + b2) at the end of another evaluation period. -

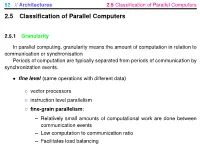

2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers

52 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.1 Granularity In parallel computing, granularity means the amount of computation in relation to communication or synchronisation Periods of computation are typically separated from periods of communication by synchronization events. • fine level (same operations with different data) ◦ vector processors ◦ instruction level parallelism ◦ fine-grain parallelism: – Relatively small amounts of computational work are done between communication events – Low computation to communication ratio – Facilitates load balancing 53 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers – Implies high communication overhead and less opportunity for per- formance enhancement – If granularity is too fine it is possible that the overhead required for communications and synchronization between tasks takes longer than the computation. • operation level (different operations simultaneously) • problem level (independent subtasks) ◦ coarse-grain parallelism: – Relatively large amounts of computational work are done between communication/synchronization events – High computation to communication ratio – Implies more opportunity for performance increase – Harder to load balance efficiently 54 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.2 Hardware: Pipelining (was used in supercomputers, e.g. Cray-1) In N elements in pipeline and for 8 element L clock cycles =) for calculation it would take L + N cycles; without pipeline L ∗ N cycles Example of good code for pipelineing: §doi =1 ,k ¤ z ( i ) =x ( i ) +y ( i ) end do ¦ 55 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers Vector processors, fast vector operations (operations on arrays). Previous example good also for vector processor (vector addition) , but, e.g. recursion – hard to optimise for vector processors Example: IntelMMX – simple vector processor. -

Microprocessor Architecture

EECE416 Microcomputer Fundamentals Microprocessor Architecture Dr. Charles Kim Howard University 1 Computer Architecture Computer System CPU (with PC, Register, SR) + Memory 2 Computer Architecture •ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit) •Binary Full Adder 3 Microprocessor Bus 4 Architecture by CPU+MEM organization Princeton (or von Neumann) Architecture MEM contains both Instruction and Data Harvard Architecture Data MEM and Instruction MEM Higher Performance Better for DSP Higher MEM Bandwidth 5 Princeton Architecture 1.Step (A): The address for the instruction to be next executed is applied (Step (B): The controller "decodes" the instruction 3.Step (C): Following completion of the instruction, the controller provides the address, to the memory unit, at which the data result generated by the operation will be stored. 6 Harvard Architecture 7 Internal Memory (“register”) External memory access is Very slow For quicker retrieval and storage Internal registers 8 Architecture by Instructions and their Executions CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer) Variety of instructions for complex tasks Instructions of varying length RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) Fewer and simpler instructions High performance microprocessors Pipelined instruction execution (several instructions are executed in parallel) 9 CISC Architecture of prior to mid-1980’s IBM390, Motorola 680x0, Intel80x86 Basic Fetch-Execute sequence to support a large number of complex instructions Complex decoding procedures Complex control unit One instruction achieves a complex task 10 -

Instruction Pipelining (1 of 7)

Chapter 5 A Closer Look at Instruction Set Architectures Objectives • Understand the factors involved in instruction set architecture design. • Gain familiarity with memory addressing modes. • Understand the concepts of instruction- level pipelining and its affect upon execution performance. 5.1 Introduction • This chapter builds upon the ideas in Chapter 4. • We present a detailed look at different instruction formats, operand types, and memory access methods. • We will see the interrelation between machine organization and instruction formats. • This leads to a deeper understanding of computer architecture in general. 5.2 Instruction Formats (1 of 31) • Instruction sets are differentiated by the following: – Number of bits per instruction. – Stack-based or register-based. – Number of explicit operands per instruction. – Operand location. – Types of operations. – Type and size of operands. 5.2 Instruction Formats (2 of 31) • Instruction set architectures are measured according to: – Main memory space occupied by a program. – Instruction complexity. – Instruction length (in bits). – Total number of instructions in the instruction set. 5.2 Instruction Formats (3 of 31) • In designing an instruction set, consideration is given to: – Instruction length. • Whether short, long, or variable. – Number of operands. – Number of addressable registers. – Memory organization. • Whether byte- or word addressable. – Addressing modes. • Choose any or all: direct, indirect or indexed. 5.2 Instruction Formats (4 of 31) • Byte ordering, or endianness, is another major architectural consideration. • If we have a two-byte integer, the integer may be stored so that the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte or vice versa. – In little endian machines, the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte. -

18-447 Computer Architecture Lecture 6: Multi-Cycle and Microprogrammed Microarchitectures

18-447 Computer Architecture Lecture 6: Multi-Cycle and Microprogrammed Microarchitectures Prof. Onur Mutlu Carnegie Mellon University Spring 2015, 1/28/2015 Agenda for Today & Next Few Lectures n Single-cycle Microarchitectures n Multi-cycle and Microprogrammed Microarchitectures n Pipelining n Issues in Pipelining: Control & Data Dependence Handling, State Maintenance and Recovery, … n Out-of-Order Execution n Issues in OoO Execution: Load-Store Handling, … 2 Reminder on Assignments n Lab 2 due next Friday (Feb 6) q Start early! n HW 1 due today n HW 2 out n Remember that all is for your benefit q Homeworks, especially so q All assignments can take time, but the goal is for you to learn very well 3 Lab 1 Grades 25 20 15 10 5 Number of Students 0 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 n Mean: 88.0 n Median: 96.0 n Standard Deviation: 16.9 4 Extra Credit for Lab Assignment 2 n Complete your normal (single-cycle) implementation first, and get it checked off in lab. n Then, implement the MIPS core using a microcoded approach similar to what we will discuss in class. n We are not specifying any particular details of the microcode format or the microarchitecture; you can be creative. n For the extra credit, the microcoded implementation should execute the same programs that your ordinary implementation does, and you should demo it by the normal lab deadline. n You will get maximum 4% of course grade n Document what you have done and demonstrate well 5 Readings for Today n P&P, Revised Appendix C q Microarchitecture of the LC-3b q Appendix A (LC-3b ISA) will be useful in following this n P&H, Appendix D q Mapping Control to Hardware n Optional q Maurice Wilkes, “The Best Way to Design an Automatic Calculating Machine,” Manchester Univ. -

Pipelining 2

Instruction-Level Parallelism Dynamic Scheduling CS448 1 Dynamic Scheduling • Static Scheduling – Compiler rearranging instructions to reduce stalls • Dynamic Scheduling – Hardware rearranges instruction stream to reduce stalls – Possible to account for dependencies that are only known at run time - e. g. memory reference – Simplifies the compiler – Code built for one pipeline in mind could also run efficiently on a different pipeline – minimizes the need for speculative slot filling - NP hard • Once a common tactic with supercomputers and mainframes but was too expensive for single-chip – Now fits on a desktop PC’s 2 1 Dynamic Scheduling • Dependencies that are close together stall the entire pipeline – DIVD F0, F2, F4 – ADDD F10, F0, F8 – SUBD F12, F8, F14 • The ADD needs the DIV to finish, so there is a stall… which also stalls the SUBD – Looong stall for DIV – But the SUBD is independent so there is no reason why we shouldn’t execute it – Or is there? • Precise Interrupts - Ignore for now • Compiler could rearrange instructions, but so could the hardware 3 Dynamic Scheduling • It would be desirable to decode instructions into the pipe in order but then let them stall individually while waiting for operands before issue to execution units. • Dynamic Scheduling – Out of Order Issue / Execution • Scoreboarding 4 2 Scoreboarding Split ID stage into two: Issue (Decode, check for Structural hazards) Read Operands (Wait until no data hazards, read operands) 5 Scoreboard Overview • Consider another example: – DIVD F0, F2, F4 – ADDD F10, F0, -

System Design for a Computational-RAM Logic-In-Memory Parailel-Processing Machine

System Design for a Computational-RAM Logic-In-Memory ParaIlel-Processing Machine Peter M. Nyasulu, B .Sc., M.Eng. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ottaw a-Carleton Ins titute for Eleceical and Computer Engineering, Department of Electronics, Faculty of Engineering, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada May, 1999 O Peter M. Nyasulu, 1999 National Library Biôiiothkque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 39S Weiiington Street 395. nie WeUingtm OnawaON KlAW Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, ban, distribute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microficbe/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Integrating several 1-bit processing elements at the sense amplifiers of a standard RAM improves the performance of massively-paralle1 applications because of the inherent parallelism and high data bandwidth inside the memory chip. -

Review of Computer Architecture

Basic Computer Architecture CSCE 496/896: Embedded Systems Witawas Srisa-an Review of Computer Architecture Credit: Most of the slides are made by Prof. Wayne Wolf who is the author of the textbook. I made some modifications to the note for clarity. Assume some background information from CSCE 430 or equivalent von Neumann architecture Memory holds data and instructions. Central processing unit (CPU) fetches instructions from memory. Separate CPU and memory distinguishes programmable computer. CPU registers help out: program counter (PC), instruction register (IR), general- purpose registers, etc. von Neumann Architecture Memory Unit Input CPU Output Unit Control + ALU Unit CPU + memory address 200PC memory data CPU 200 ADD r5,r1,r3 ADD IRr5,r1,r3 Recalling Pipelining Recalling Pipelining What is a potential Problem with von Neumann Architecture? Harvard architecture address data memory data PC CPU address program memory data von Neumann vs. Harvard Harvard can’t use self-modifying code. Harvard allows two simultaneous memory fetches. Most DSPs (e.g Blackfin from ADI) use Harvard architecture for streaming data: greater memory bandwidth. different memory bit depths between instruction and data. more predictable bandwidth. Today’s Processors Harvard or von Neumann? RISC vs. CISC Complex instruction set computer (CISC): many addressing modes; many operations. Reduced instruction set computer (RISC): load/store; pipelinable instructions. Instruction set characteristics Fixed vs. variable length. Addressing modes. Number of operands. Types of operands. Tensilica Xtensa RISC based variable length But not CISC Programming model Programming model: registers visible to the programmer. Some registers are not visible (IR). Multiple implementations Successful architectures have several implementations: varying clock speeds; different bus widths; different cache sizes, associativities, configurations; local memory, etc. -

Micro-Circuits for High Energy Physics*

MICRO-CIRCUITS FOR HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS* Paul F. Kunz Stanford Linear Accelerator Center Stanford University, Stanford, California, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Microprogramming is an inherently elegant method for implementing many digital systems. It is a mixture of hardware and software techniques with the logic subsystems controlled by "instructions" stored Figure 1: Basic TTL Gate in a memory. In the past, designing microprogrammed systems was difficult, tedious, and expensive because the available components were capable of only limited number of functions. Today, however, large blocks of microprogrammed systems have been incorporated into a A input B input C output single I.e., thus microprogramming has become a simple, practical method. false false true false true true true false true true true false 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BRIEF HISTORY OF MICROCIRCUITS Figure 2: Truth Table for NAND Gate. The first question which arises when one talks about microcircuits is: What is a microcircuit? The answer is simple: a complete circuit within a single integrated-circuit (I.e.) package or chip. The next question one might ask is: What circuits are available? The answer to this question is also simple: it depends. It depends on the economics of the circuit for the semiconductor manufacturer, which depends on the technology he uses, which in turn changes as a function of time. Thus to understand Figure 3: Logical NOT Circuit. what microcircuits are available today and what makes them different from those of yesterday it is interesting to look into the economics of producing microcircuits. The basic element in a logic circuit is a gate, which is a circuit with a number of inputs and one output and it performs a basic logical function such as AND, OR, or NOT. -

EECS 570 Lecture 5 GPU Winter 2021 Prof

EECS 570 Lecture 5 GPU Winter 2021 Prof. Satish Narayanasamy http://www.eecs.umich.edu/courses/eecs570/ Slides developed in part by Profs. Adve, Falsafi, Martin, Roth, Nowatzyk, and Wenisch of EPFL, CMU, UPenn, U-M, UIUC. 1 EECS 570 • Slides developed in part by Profs. Adve, Falsafi, Martin, Roth, Nowatzyk, and Wenisch of EPFL, CMU, UPenn, U-M, UIUC. Discussion this week • Term project • Form teams and start to work on identifying a problem you want to work on Readings For next Monday (Lecture 6): • Michael Scott. Shared-Memory Synchronization. Morgan & Claypool Synthesis Lectures on Computer Architecture (Ch. 1, 4.0-4.3.3, 5.0-5.2.5). • Alain Kagi, Doug Burger, and Jim Goodman. Efficient Synchronization: Let Them Eat QOLB, Proc. 24th International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA 24), June, 1997. For next Wednesday (Lecture 7): • Michael Scott. Shared-Memory Synchronization. Morgan & Claypool Synthesis Lectures on Computer Architecture (Ch. 8-8.3). • M. Herlihy, Wait-Free Synchronization, ACM Trans. Program. Lang. Syst. 13(1): 124-149 (1991). Today’s GPU’s “SIMT” Model CIS 501 (Martin): Vectors 5 Graphics Processing Units (GPU) • Killer app for parallelism: graphics (3D games) Tesla S870 What is Behind such an Evolution? • The GPU is specialized for compute-intensive, highly data parallel computation (exactly what graphics rendering is about) ❒ So, more transistors can be devoted to data processing rather than data caching and flow control ALU ALU Control ALU ALU CPU GPU Cache DRAM DRAM • The fast-growing video game industry -

P4080 Development System User's Guide

Freescale Semiconductor Document Number: P4080DSUG User Guide Rev. 0, 07/2010 P4080 Development System User’s Guide by Networking and Multimedia Group Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. Austin, TX Contents 1Overview 1. Overview . 1 2. Features Summary . 2 The P4080 development system (DS) is a high-performance 3. Block Diagram and Placement . 4 computing, evaluation, and development platform 4. Evaluation Support . 6 supporting the P4080 Power Architecture® processor. The 5. Architecture . 8 P4080 development system’s official designation is 6. Configuration . 40 7. Programming Model . 45 P4080DS, and may be ordered using this part number. 8. Revision History . 58 The P4080DS is designed to the ATX form-factor standard, A. References . 58 allowing it to be used in 2U rack-mount chassis, as well as in a standard ATX chassis. The system is lead-free and RoHS-compliant. © 2011 Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. All rights reserved. Features Summary 2 Features Summary The features of the P4080DS development board are as follows: • Support for the P4080 processor — Core processors – Eight e500mc cores – 45 nm SOI process technology — High-speed serial port (SerDes) – Eighteen lanes, dividable into many combinations – Five controllers support five add-in card slots. – Supports PCI Express, SGMII, Nexus/Aurora debug, XAUI, and Serial RapidIO®. — Dual DDR memory controllers – Designed for DDR3 support – One-per-channel 240-pin sockets that support standard JEDEC DIMMs — Triple-speed Ethernet/ USB controller – One 10/100/1G port uses on-board VSC8244 PHY -

14 Superscalar Processors

UNIT- 5 Chapter 14 Instruction Level Parallelism and Superscalar Processors What is Superscalar? • Use multiple independent instruction pipeline. • Instruction level parallelism • Identify dependencies in program • Eliminate Unnecessary dependencies • Use additional registers & renaming of register references in original code. • Branch prediction improves efficiency What is Superscalar? • RISC-like instructions, one per word • Multiple parallel execution units • Reorders and optimizes instruction stream at run time • Branch prediction with speculative execution of one path • Loads data from memory only when needed, and tries to find the data in the caches first Why Superscalar? • In 1987, scalar instruction • Most operations are on scalar quantities • Improving these operations to get an overall improvement • High performance microprocessors. General Superscalar Organization Superscalar V/S Superpipelined • Ordinary:- • One instruction/clock cycle & can perform one pipeline stage per clock cycle. • Superpipelined:- • 2 pipeline stage per cycle • Execution time:-half a clock cycle • Double internal clock speed gets two tasks per external clock cycle • Superscalar :- • allows parallel fetch execute • Start of the program & at branch target it performs better than above said. Superscalar v Superpipeline Limitations • Instruction level parallelism • Compiler based optimisation • Hardware techniques • Limited by —True data dependency —Procedural dependency —Resource conflicts —Output dependency —Antidependency True Data Dependency • ADD r1,