1796 Hatsell 1 Privilege of Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronicles of the Family Baker"

Chronicles of the Family by Lee C.Baker i ii Table of Contents 1 THE MEDIEVAL BAKERS........................................................................................1 2 THE BAKERS OF SISSINGHURST.........................................................................20 3 THE BAKERS OF LONDON AND OXFORD ............................................................49 4 THE BAKERS AT HOTHFIELD ..............................................................................58 5 COMING OUT OF ENGLAND.................................................................................70 6 THE DAYS AT MILFORD .......................................................................................85 7 EAST HAMPTON, L. I. ...........................................................................................96 8 AMAGANSETT BY THE SEA ................................................................................114 9 STATEN ISLAND AND NEW AMSTERDAM ..........................................................127 10 THE ELIZABETH TOWN PIONEERS ....................................................................138 11 THE BAKERS OF ELIZABETH TOWN AND WESTFIELD ......................................171 12 THE NEIGHBORS AT NEWARK...........................................................................198 13 THE NEIGHBORS AT RAHWAY ...........................................................................208 14 WHO IS JONATHAN BAKER?..............................................................................219 15 THE JONATHAN I. BAKER CONFUSION -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Stapylton Final Version

1 THE PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE OF FREEDOM FROM ARREST, 1603–1629 Keith A. T. Stapylton UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Page 2 DECLARATION I, Keith Anthony Thomas Stapylton, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed Page 3 ABSTRACT This thesis considers the English parliamentary privilege of freedom from arrest (and other legal processes), 1603-1629. Although it is under-represented in the historiography, the early Stuart Commons cherished this particular privilege as much as they valued freedom of speech. Previously one of the privileges requested from the monarch at the start of a parliament, by the seventeenth century freedom from arrest was increasingly claimed as an ‘ancient’, ‘undoubted’ right that secured the attendance of members, and safeguarded their honour, dignity, property, and ‘necessary’ servants. Uncertainty over the status and operation of the privilege was a major contemporary issue, and this prompted key questions for research. First, did ill definition of the constitutional relationship between the crown and its prerogatives, and parliament and its privileges, lead to tensions, increasingly polemical attitudes, and a questioning of the royal prerogative? Where did sovereignty now lie? Second, was it important to maximise the scope of the privilege, if parliament was to carry out its business properly? Did ad hoc management of individual privilege cases nevertheless have the cumulative effect of enhancing the authority and confidence of the Commons? Third, to what extent was the exploitation or abuse of privilege an unintended consequence of the strengthening of the Commons’ authority in matters of privilege? Such matters are not treated discretely, but are embedded within chapters that follow a thematic, broadly chronological approach. -

Subject Indexes

Subject Indexes. p.4: Accession Day celebrations (November 17). p.14: Accession Day: London and county index. p.17: Accidents. p.18: Accounts and account-books. p.20: Alchemists and alchemy. p.21: Almoners. p.22: Alms-giving, Maundy, Alms-houses. p.25: Animals. p.26: Apothecaries. p.27: Apparel: general. p.32: Apparel, Statutes of. p.32: Archery. p.33: Architecture, building. p.34: Armada; other attempted invasions, Scottish Border incursions. p.37: Armour and armourers. p.38: Astrology, prophecies, prophets. p.39: Banqueting-houses. p.40: Barges and Watermen. p.42: Battles. p.43: Birds, and Hawking. p.44: Birthday of Queen (Sept 7): celebrations; London and county index. p.46: Calendar. p.46: Calligraphy and Characterie (shorthand). p.47: Carts, carters, cart-takers. p.48: Catholics: selected references. p.50: Census. p.51: Chapel Royal. p.53: Children. p.55: Churches and cathedrals visited by Queen. p.56: Church furnishings; church monuments. p.59: Churchwardens’ accounts: chronological list. p.72: Churchwardens’ accounts: London and county index. Ciphers: see Secret messages, and ciphers. p.76: City and town accounts. p.79: Clergy: selected references. p.81: Clergy: sermons index. p.88: Climate and natural phenomena. p.90: Coats of arms. p.92: Coinage and coins. p.92: Cooks and kitchens. p.93: Coronation. p.94: Court ceremonial and festivities. p.96: Court disputes. p.98: Crime. p.101: Customs, customs officers. p.102: Disease, illness, accidents, of the Queen. p.105: Disease and illness: general. p.108: Disease: Plague. p.110: Disease: Smallpox. p.110: Duels and Challenges to Duels. -

The Heraldic Screens of Middlewich, Cheshire. By

THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Fourth Series Volume I 2018 Number 235 in the original series started in 1952 Founding Editor † John P.B.Brooke-Little, C.V.O, M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editor Dr Paul A Fox, M.A., F.S.A, F.H.S., F.R.C.P., A.I.H. Reviews Editor Tom O’Donnell, M.A., M.PHIL. Editorial Panel Dr Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S., A.I.H. Dr Jackson W Armstrong, B.A., M.PHIL., PH.D. Steven Ashley, F.S.A, a.i.h. Dr Claire Boudreau, PH.D., F.R.H.S.C., A.I.H., Chief Herald of Canada Prof D’Arcy J.D.Boulton, M.A., PH.D., D.PHIL., F.S.A., A.I.H. Dr Clive.E.A.Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., F.S.A., Richmond Herald Steen Clemmensen A.I.H. M. Peter D.O’Donoghue, M.A., F.S.A., York Herald Dr Andrew Gray, PH.D., F.H.S. Jun-Prof Dr Torsten Hiltmann, PH.D., a.i.h Prof Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard, PH.D., F.R.Hist.S., A.I.H. Elizabeth Roads, L.V.O., F.S.A., F.H.S., A.I.H, Snawdoun Herald Advertising Manager John J. Tunesi of Liongam, M.Sc., FSA Scot., Hon.F.H.S., Q.G. Guidance for authors will be found online at www.theheraldrysociety.com THE HERALDIC SCREENS OF MIDDLEWICH, CHESHIRE ANTHONY BOSTOCK MA Abstract Two screens in St Michael’s church Middlewich which have not previously excited the interest of antiquarians are in the process of being conserved by the Middlewich Heritage Trust with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund. -

1818 Hatsell 1 Privilege of Parliament

1818_HATSELL_1 PRIVILEGE OF PARLIAMENT [John Hatsell] Precedents of Proceedings in the House of Commons; Under Separate Titles. With Observations. In Four Volumes. Vol. I. Relating To Privilege Of Parliament; From The Earliest Records, To The Year 1628: With Observations Upon The Reign Of Car. I. From 1628 To 4 January 1641. A New Edition, with Additions. (London: Printed by Luke Hansard and Sons, Near Lincoln’s-Inn Fields and Sold by Payne and Foss, Pall-Mall; Cadell and Davies, in the Strand, and Clarke and Sons, Portugal-Street, Lincoln’s-Inn. 1818). \\Ed. Note: Research Note No. 1 titled ‘Editorial Practices’ covers the basic details of transcription and presentation of this volume of Hatsell’s Precedents of Proceedings in the House of Commons. What follows is the machine-readable edition (my MS Word, your PDF) that includes all text of the original as follows including title page/s, preface/s, table of contents and footnotes but excluding running chapter heads and index. The raw/gross word count is 101,989. Original pagination indicated by numbers within squiggly brackets { }. A very few backwards slashes \\ \\ embrace an editorial note that I crafted, including this paragraph.\\ {iii} PRECEDENTS OF PROCEEDINGS IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS; WITH OBSERVATIONS. _____________ IN FOUR VOLUMES: VOL. I.—PRIVILEGE OF PARLIAMENT. VOL. II.—MEMBERS, SPEAKER, &c. VOL. III.—LORDS, AND SUPPLY. VOL. IV.—CONFERENCE, AND IMPEACHMENT. -------------------- A NEW EDITION, WITH ADDITIONS. ------------------- LONDON: PRINTED BY LUKE HANSARD AND SONS, NEAR LINCOLN’S-INN FIELDS AND SOLD BY PAYNE AND FOSS, PALL-MALL; CADELL AND DAVIES, IN THE STRAND, AND CLARKE AND SONS, PORTUGAL-STREET, LINCOLN’S-INN. -

The Hidden Index of Hungerford Names and Places

The Hidden Index of Hungerford Names This alphabetical index of names was compiled over many years of research by Norman and Joyce Hidden. It comprises a number of notes and references that may prove of use to future researchers. The list includes about 1,500 names. Note the varied spelling of names in the medieval period. Transcribed by Dr Hugh Pihlens, 2014. Key to Abbreviations: BER Records at Reading University CR Close Rolls CUR Curia Regis Rolls DL Duchy of Lancaster records at National Archives FA Huntington nn Huntington microfilem number nn IPM Inquisition Post Mortem PL PR Patent Rolls (later Patent Register) PRM/PRB/PRC Parish Registers – Marriages / Burials / Christenings?? [Sometimes the call number at BRO or WRO is given] Abbessesometer, William 1313 PR Abbotestone, Thomas 1428 FA Abraham, John (49 Ed III) IPM Abyndon, Abbot of (6 Ric II) IPM; (20/21 H VII) IPM Achard, Sir Robert 1340 CR Achard, William 1208 CUR Ailgar/Aylgar/Elger, John 1359 (32 Ed III) IPM; aged 40, at Kintbury, on behalf of Polehampton; 1355 witness deed of Walter Hungerford (Hastings MS 1194); 1395 Prnct Deed B 1390 Ailmere, John 1400 CR Alan c1248 Bec Custumal (T/S p.3) Alden, Thomas born c1508; 1547 Lay subsidy Chilton Foliat (E179/197/244); 1578 DL4/20/53 and DL4/19/53 Deposition in Iremonger v Hidden, yeoman of Chilton, 70 yrs of age and servant to Sir Edward Darrell kt (d 1549) or Mrs Fortescue (who had a life interest in the Darrell estate after Sir Edward’s death); 1597 PCC will of Thomas Osmond “to Agnes Cannon my sister I give all goods that Thos Alden my grandfather gave me by deed of gift”. -

Memoirs of the City of London and Its Celebrities. (Volume 2)

MEMOIRS OF THE CITY OF LONDON AND ITS CELEBRITIES. (VOLUME 2) By John Heneage Jesse CHAPTER I. THE PRIORY AND CHURCH OF ST. BARTHOLOMEW. St. Bartholomew's Priory and Church When, Btfilt.-j-Jt* Present Appearance Refectory, Crypt, and Subterranean Passage Bartholomew Close Monuments in the Church Story of Rahere, Founder of the Priory Fracas in the Priory St. Bartholomew's Hospital Canonbury Canonbury Tower Goldsmith's Residence Prior Bolton's Residence Bartholomew Fair. ON the southeastern side of Smithfield stand the remains of the beautiful church and once vast and wealthy priory of St. Bartholomew, founded by Rahere, the first prior, in the reign of Henry the First. At the time of the suppression of the religious houses in the reign of Henry the Eighth, it was distinguished by its vast extent of building, its beautiful and shady gardens, its exquisite cloisters, its grand refectory, its fish-ponds, and by all the appurtenances of a great monastic establishment. Its mulberry garden, planted by Prior Bolton, was famous. Passing under a gateway rich with carved roses and zigzag ornaments, we enter the fine old church of St. Bartholomew. As we gaze on the solidity of its massive pillars, its graceful arches, and the beauty of its architectural details, we are at once impressed with that sense of grandeur and solemnity which only such a scene can inspire. The remains of the old church are in the Norman style of architecture, and are apparently of the same date as the earlier portions of Winchester, Cathp^r?.!. Some notion of its former magnificen.ce. -

Prominent Elizabethans

Prominent Elizabethans. p.1: Church; p.2: Law Officers. p.3: Miscellaneous Officers of State. p.5: Royal Household Officers. p.7: Privy Councillors. p.9: Peerages. p.11: Knights of the Garter and Garter ceremonies. p.18: Knights: chronological list; p.22: alphabetical list. p.26: Knights: miscellaneous references; Knights of St Michael. p.27-162: Prominent Elizabethans. Church: Archbishops, two Bishops, four Deans. Dates of confirmation/consecration. Archbishop of Canterbury. 1556: Reginald Pole, Archbishop and Cardinal; died 1558 Nov 17. Vacant 1558-1559 December. 1559 Dec 17: Matthew Parker; died 1575 May 17. 1576 Feb 15: Edmund Grindal; died 1583 July 6. 1583 Sept 23: John Whitgift; died 1604. Archbishop of York. 1555: Nicholas Heath; deprived 1559 July 5. 1560 Aug 8: William May elected; died the same day. 1561 Feb 25: Thomas Young; died 1568 June 26. 1570 May 22: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1576. 1577 March 8: Edwin Sandys; died 1588 July 10. 1589 Feb 19: John Piers; died 1594 Sept 28. 1595 March 24: Matthew Hutton; died 1606. Bishop of London. 1553: Edmund Bonner; deprived 1559 May 29; died in prison 1569. 1559 Dec 21: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of York 1570. 1570 July 13: Edwin Sandys; became Archbishop of York 1577. 1577 March 24: John Aylmer; died 1594 June 5. 1595 Jan 10: Richard Fletcher; died 1596 June 15. 1597 May 8: Richard Bancroft; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1604. Bishop of Durham. 1530: Cuthbert Tunstall; resigned 1559 Sept 28; died Nov 18. 1561 March 2: James Pilkington; died 1576 Jan 23. 1577 May 9: Richard Barnes; died 1587 Aug 24. -

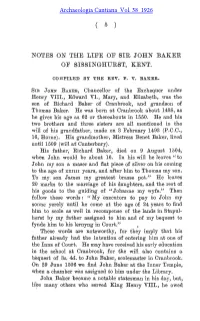

Notes on the Life of Sir John Baker of Sissinghurst, Kent

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 38 1926 NOTES ON THE LIFE OF SIR, JOHN BAKER OF SISSINGHURST, KENT. COMPILED BY THE REV. F. V. BAKER. SIB JOHN BAKER, Chancellor of the Exchequer under Henry VIII., Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth, was the son of Richard Baker of Cranbrook, and grandson of Thomas Baker. He was born at Cranbrook about 1488, as he gives his age as 62 or thereabouts in 1550. He and his two brothers and three sisters are all mentioned in the will of his grandfather, made on 3 February 1493 (P.C.C., 16, Home). His grandmother, Mistress Benet Baker, lived until 1509 (will at'Canterbury). His father, Richard Baker, died on 9 August 1504, when John would be about 16. In his will he leaves " to John my son a niaser and flat piece of silver on his coming to the age of xxiui years, and after him to Thomas my son. To my. son James my greatest brasse pot." He leaves 20 marks to the marriage of his daughters, and the rest of his goods to the guiding of "Johanne my wyfe." Then follow these words: " My executors to pay to John my sonne yerely until he come at the age of 24 years to find him to scole as well in recompense of the lands in Stapul- her'st by my father assigned to him and of my bequest to fynde him to his lernyng in Court." These words are noteworthy, for they imply that his father already had the intention of entering him at one of the Inns of Court. -

One of Many: Martial Law and English Laws C. 1500 – C. 1700 John

One of Many: Martial Law and English Laws c. 1500 – c. 1700 John Michael Collins Minneapolis, MN Bachelor of Arts, with honors, Northwestern University, 2006 MPHIL, with distinction, Cambridge University, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August 2013 Abstract This dissertation provides the first history of martial law in the early modern period. It seeks to reintegrate martial law in the larger history of English law. It shows how jurisdictional barriers constructed by the makers of the Petition of Right Parliament for martial law unintentionally transformed the concept from a complementary form of criminal law into an all-encompassing jurisdiction imposed by governors and generals during times of crisis. Martial law in the early modern period was procedure. The Tudor Crown made it in order to terrorize hostile populations into obedience and to avoid potential jury nullification. The usefulness of martial law led Crown deputies in Ireland to adapt martial law procedure to meet the legal challenges specific to their environment. By the end of the sixteenth century, Crown officers used martial law on vagrants, rioters, traitors, soldiers, sailors, and a variety of other wrongs. Generals, meanwhile, sought to improve the discipline within their forces in order to better compete with their rivals on the European continent. Over the course of the seventeenth century, owing to this desire, they transformed martial law substance, procedure, and administration. The usefulness of martial law made many worried, and MPs in 1628 sought to restrain martial law to a state of war, defined either as the Courts of Westminster being closed or by the presence of the enemy’s army with its standard raised. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1559

1559 1559 At WHITEHALL PALACE Jan 1,Sun New Year gifts. The exchange of gifts at New Year was a general custom, replaced in later centuries by exchanging gifts at Christmas. Although the new year officially began on March 25, gifts were exchanged on January 1. New Year Gift Rolls list gifts to and from the Queen, in order of the giver or recipient’s rank, from a Duchess, or the Lord Chancellor, down to some of the kitchen staff. The Rolls survive only for 24 years of the reign. Archbishops and Bishops gave a purse of money, as did many lords, ladies, and knights. Others gave jewellery, items of wearing apparel, books, pictures, food, wine, musical instruments, or more exotic gifts. A servant came to the palace with the gift to the Queen and received a monetary ‘reward’. The gifts were displayed on long tables for the Queen to see. The royal official who took custody of a gift was listed on the Roll. During the next few days the Queen’s gift was delivered to those who had made gifts to her, who in turn rewarded the bringer. The Queen invariably gave gilt plate, usually in the form of a cup or bowl; the weight in ounces was noted. A small selection only of the gifts to her is given here, and includes the books, maps, and pictures (as most likely to have survived), and animals, and a few of the other gifts. The Rolls are published in The Elizabethan New Year’s Gift Exchanges 1559-1603, edited by Jane A.