View Was Provided by the National Endowment for the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

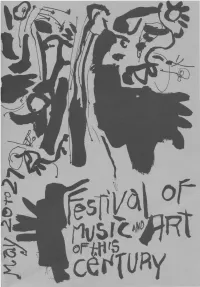

1962 FMAC SS.Pdf

WIND DRUM The music of WIND DRUM is composed on a six-tone scale. In South India, this scale is called "hamsanandi," in North India, "marava." In North India, this scale would be played before sunset. The notes are C, D flat, E, F sharp, A, and B. PREFACE The mountain island of Hawaii becomes a symbol of an island universe in an endless ocean of nothingness, of space, of sleep. This is the night of Brahma. Time swings back and forth, time, the giant pendulum of the universe. As time swings forward all things waken out of endless slumber, all things grow, dance, and sing. Motion brings storm, whirlwind, tornado, devastation, destruction, and annihilation. All things fall into death. But with total despair comes sudden surprise. The super natural commands with infinite majesty. All storms, all motions cease. Only the celestial sounds of the Azura Heavens are heard. Time swings back, death becomes life, resurrection. All things are reborn, grow, dance, and sing. But the spirit of ocean slumber approaches and all things fall back again into sleep and emptiness, the state of endless nothingness symbolized by ocean. The night of Brahma returns. LIBRETTO I VI Stone, water, singing grass, Flute of Azura, Singing tree, singing mountain, Fill heaven with celestial sound! Praise ever-compassionate One. Death, become life! II VII Island of mist, Sun, melt, dissolve Awake from ocean Black-haired mountain storm, Of endless slumber. Life drum sing, III Stone drum ring! Snow mountain, VIII Dance on green hills. Trees singing of branches IV Sway winds, Three hills, Forest dance on hills, Dance on forest, Hills, green, dance on Winds, sway branches Mountain snow. -

Oral History T-0001 Interviewees: Chick Finney and Martin Luther Mackay Interviewer: Irene Cortinovis Jazzman Project April 6, 1971

ORAL HISTORY T-0001 INTERVIEWEES: CHICK FINNEY AND MARTIN LUTHER MACKAY INTERVIEWER: IRENE CORTINOVIS JAZZMAN PROJECT APRIL 6, 1971 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Today is April 6, 1971 and this is Irene Cortinovis of the Archives of the University of Missouri. I have with me today Mr. Chick Finney and Mr. Martin L. MacKay who have agreed to make a tape recording with me for our Oral History Section. They are musicians from St. Louis of long standing and we are going to talk today about their early lives and also about their experiences on the music scene in St. Louis. CORTINOVIS: First, I'll ask you a few questions, gentlemen. Did you ever play on any of the Mississippi riverboats, the J.S, The St. Paul or the President? FINNEY: I never did play on any of those name boats, any of those that you just named, Mrs. Cortinovis, but I was a member of the St. Louis Crackerjacks and we played on kind of an unknown boat that went down the river to Cincinnati and parts of Kentucky. But I just can't think of the name of the boat, because it was a small boat. Do you need the name of the boat? CORTINOVIS: No. I don't need the name of the boat. FINNEY: Mrs. Cortinovis, this is Martin McKay who is a name drummer who played with all the big bands from Count Basie to Duke Ellington. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

J. Dorsey, Earl Hines Also Swell Trombone Showcased

DOWN BEAT Chicago. April 15. 1941 Chicago fl by his latest cutting. Everything Depends On You, in which he spots Gems of Jazz’ and Kirby Madeline Green and a male vocal trio. On BBird 11036, it’s a side which shows a new Hines, a Hines who can bow to the public’s de Albarns Draw Big Raves; mands and yet maintain a high artistic plane. Backer is In Suiamp Lande, a juniper, with the leader’s I—Oh Le 88, Franz Jackson’s tenor and a »—New ' J. Dorsey, Earl Hines Also swell trombone showcased. Je Uy, 3—dmapi Jelly (BBird 11065) slow 4—Perfid by DAVE DEXTER, JR. blues with more sprightly Hines, 5—The A and a Pha Terrelish v ical by Bill 6—High I JvlUSICIANS SHOULD FIND the new “Gems of Jazz” and Eckstein. Flipover, I’m Falling 7—There' For You, is the only really bad John Kirby albums of interest, for the two collections em side of the four. It’s a draggy pop 9—Chapeí brace a little bit of everything in the jazz field. The “Gems” with too much Eckstein. [O—Th> l include 12 exceptional sides featuring Mildred Bailey, Jess 11—f Unti Stacy, Lux Lewis, Joe Marsala and Bud Freeman. Made in Jimmy Dorsey 12—Frenes 1936, they’ were issued only in England on Parlophone and Hot as a gang of ants on a WATCH O have been unavailable domestically until now. warm rock, Jim and his gang click again with two new Tudi« Cama Ma «mvng tl B a i 1 ey’s rata versions uf Yours (the Man Behind the Counter in soda-jerk getup in that rat. -

“Until That Song Is Born”: an Ethnographic Investigation of Teaching and Learning Among Collaborative Songwriters in Nashville

“UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Music Education—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT “UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill With the intent of informing the practice of music educators who teach songwriting in K– 12 and college/university classrooms, the purpose of this research is to examine how professional songwriters in Nashville, Tennessee—one of songwriting’s professional “hubs”—teach and learn from one another in the process of engaging in collaborative songwriting. This study viewed songwriting as a form of “situated learning” (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and “situated practice” (Folkestad, 2012) whose investigation requires consideration of the professional culture that surrounds creative activity in a specific context (i.e., Nashville). The following research questions guided this study: (1) How do collaborative songwriters describe the process of being inducted to, and learning within, the practice of professional songwriting in Nashville, (2) What teaching and learning behaviors can be identified in the collaborative songwriting processes of Nashville songwriters, and (3) Who are the important actors in the process of learning to be a collaborative songwriter in Nashville, and what roles do they play (e.g., gatekeeper, mentor, role model)? This study combined elements of case study and ethnography. Data sources included observation of co-writing sessions, interviews with songwriters, and participation in and observation of open mic and writers’ nights. -

CATALOGUE WELCOME to NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS and NAXOS NOSTALGIA, Twin Compendiums Presenting the Best in Vintage Popular Music

NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS/NOSTALGIA CATALOGUE WELCOME TO NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS AND NAXOS NOSTALGIA, twin compendiums presenting the best in vintage popular music. Following in the footsteps of Naxos Historical, with its wealth of classical recordings from the golden age of the gramophone, these two upbeat labels put the stars of yesteryear back into the spotlight through glorious new restorations that capture their true essence as never before. NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS documents the most vibrant period in the history of jazz, from the swinging ’20s to the innovative ’40s. Boasting a formidable roster of artists who forever changed the face of jazz, Naxos Jazz Legends focuses on the true giants of jazz, from the fathers of the early styles, to the queens of jazz vocalists and the great innovators of the 1940s and 1950s. NAXOS NOSTALGIA presents a similarly stunning line-up of all-time greats from the golden age of popular entertainment. Featuring the biggest stars of stage and screen performing some of the best- loved hits from the first half of the 20th century, this is a real treasure trove for fans to explore. RESTORING THE STARS OF THE PAST TO THEIR FORMER GLORY, by transforming old 78 rpm recordings into bright-sounding CDs, is an intricate task performed for Naxos by leading specialist producer-engineers using state-of-the-art-equipment. With vast personal collections at their disposal, as well as access to private and institutional libraries, they ensure that only the best available resources are used. The records are first cleaned using special equipment, carefully centred on a heavy-duty turntable, checked for the correct playing speed (often not 78 rpm), then played with the appropriate size of precision stylus. -

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus the Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, Conducting

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus The Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, conducting ALAN HOVHANESS is one of those composers whose music seems to prove the inexhaustability of the ancient modes and of the seven tones of the diatonic scale. He has made for himself one of the most individual styles to be found in the work of any American composer, recognizable immediately for its exotic flavor, its masterly simplicity, and its constant air of discovering unexpected treasures at each turn of the road. Meditation on Orpheus, scored for full symphony orchestra, is typical of Hovhaness’ work in the delicate construction of its sonorities. A single, pianissimo tam-tam note, a tone from a solo horn, an evanescent pizzicato murmur from the violins (senza misura)—these ethereal elements tinge the sound of the middle and lower strings at the work’s beginning and evoke an ambience of mysterious dignity and sensuousness which continues and grows throughout the Meditation. At intervals, a strange rushing sound grows to a crescendo and subsides, interrupting the flow of smooth melody for a moment, and then allowing it to resume, generally with a subtle change of scene. The senza misura pizzicato which is heard at the opening would seem to be the germ from which this unusual passage has grown, for the “rushing” sound—dynamically intensified at each appearance—is produced by the combination of fast, metrically unmeasured figurations, usually played by the strings. The composer indicates not that these passages are to be played in 2/4, 3/4, etc. but that they are to last “about 20 seconds, ad lib.” The notes are to be “rapid but not together.” They produce a fascinating effect, and somehow give the impression that other worldly significances are hidden in the juxtaposition of flow and mystical interruption. -

TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007) Interviewee: Toshiko Akiyoshi 穐吉敏子 (December 12, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Dates: June 29, 2008 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript 97 pp. Brown: Today is June 29th, 2008, and this is the oral history interview conducted with Toshiko Akiyoshi in her house on 38 W. 94th Street in Manhattan, New York. Good afternoon, Toshiko-san! Akiyoshi: Good afternoon! Brown: At long last, I‟m so honored to be able to conduct this oral history interview with you. It‟s been about ten years since we last saw each other—we had a chance to talk at the Monterey Jazz Festival—but this interview we want you to tell your life history, so we want to start at the very beginning, starting [with] as much information as you can tell us about your family. First, if you can give us your birth name, your complete birth name. Akiyoshi: To-shi-ko. Brown: Akiyoshi. Akiyoshi: Just the way you pronounced. Brown: Oh, okay [laughs]. So, Toshiko Akiyoshi. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Akiyoshi: Yes. Brown: And does “Toshiko” mean anything special in Japanese? Akiyoshi: Well, I think,…all names, as you know, Japanese names depends on the kanji [Chinese ideographs]. Different kanji means different [things], pronounce it the same way. And mine is “Toshiko,” [which means] something like “sensitive,” “susceptible,” something to do with a dark sort of nature. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

Alan Hovhaness: Exile Symphony Armenian Rhapsodies No

ALAN HOVHANESS: EXILE SYMPHONY ARMENIAN RHAPSODIES NO. 1-3 | SONG OF THE SEA | CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE AND STRINGS [1] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 1, Op. 45 (1944) 5:35 SONG OF THE SEA (1933) ALAN HOVHANESS (1911–2000) John McDonald, piano ARMENIAN RHAPSODIES NO. 1-3 [2] I. Moderato espressivo 3:39 [3] II. Adagio espressivo 2:47 SONG OF THE SEA [4] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 2, Op. 51 (1944) 8:56 CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE AND STRINGS, Op. 344 (1980) AND STRINGS Kenneth Radnofsky, soprano saxophone [5] I. Andante; Fuga 5:55 SYMPHONY NO. 1, EXILE [6] II. Adagio espressivo; Allegro 4:55 [7] III. Let the Living and the Celestial Sing 6:23 JOHN McDONALD piano [8] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 3, Op. 189 (1944) 6:40 KENNETH RADNOFSKY soprano saxophone SYMPHONY NO. 1, EXILE, Op. 17, No. 2 (1936) [9] I. Andante espressivo; Allegro 9:08 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [10] II. Grazioso 3:31 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR [11] III. Finale: Andante; Presto 10:06 TOTAL 67:39 RETROSPECTIVE them. But I’ll print some music of my own as I get a little money and help out because I really don’t care; I’m very happy when a thing is performed and performed well. And I don’t know, I live very simply. I have certain very strong feelings which I think many people have Alan Hovhaness wrote music that was both unusual and communicative. In his work, the about what we’re doing and what we’re doing wrong. archaic and the avant-garde are merged, always with melody as the primary focus. -

Tommy Dorsey 1 9

Glenn Miller Archives TOMMY DORSEY 1 9 3 7 Prepared by: DENNIS M. SPRAGG CHRONOLOGY Part 1 - Chapter 3 Updated February 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS January 1937 ................................................................................................................. 3 February 1937 .............................................................................................................. 22 March 1937 .................................................................................................................. 34 April 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 53 May 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 68 June 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 85 July 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 95 August 1937 ............................................................................................................... 111 September 1937 ......................................................................................................... 122 October 1937 ............................................................................................................. 138 November 1937 .........................................................................................................