ED268550.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FULLERTON OBSERVER FULLERTON Olds Became Infected

I Property of Fullerton Public Library, Local History Room Community & Fine Arts Calendars Pages 11-14 Fullerton’s Only Local, Independent Newspaper • Est. 1978 (printed on recycled paper) # 330 December 1,1999 Bushala Bros to ap p en in gs FUL*i ERTQN OBSERVER DECEMBER 1 1999 Market Truslow TCD Dec 1 - AIDS Quilt • 10am to 1pm Fullerton as High-Rise College Student Center. 341 East Chapman Ave. Apartment Site Info booths, testimonial videos and Quilt viewing. by Jack Harloe 33.4 million men, women & children are living with HIV/AIDS. In 1998 more T wo blocks of properties, owned by than 2.5 million 15-24 year the Bushala Bros., Inc.have been re olds became infected. To zoned R5- High Density. Mayor Rory increase awareness of the and planning Commissioner Ballard global epidemic, the questioned the legality of the action college sponsors various noting that the first hearing on the activities as part of the request occurred in 1989. Develop 12th Annual World AIDS ment Services Director Paul Dudley Day. Public invited. 992- assured the Council that the 10 year 7705 or 992-7414 lapse between 1st and 2nd readings of the request was of no concern, as there THURS Dec 2 -AIDS Quilt had been no other changes in that area • Sunny Hills High School of town during the 10 year span. The 1801 Warburton Way. The The Bushala family ask. and receive changes that make their property across the tracks zone change now approved by the Coun community is invited to from the train station attractive to high-rise developers cil will permit the Bushala’s to go with come view the memorial in the market, creating almost anything the schools gym. -

For the First Time in Sunny Hills History, the ASB Has Added a Freshman, Sophomore and Junior Princess to the Homecoming Court

the accolade VOLUME LIX, ISSUE II // SUNNY HILLS HIGH SCHOOL 1801 LANCER WAY, FULLERTON, CA 92833 // SEPT. 28, 2018 JAIME PARK | theaccolade Homecoming Royalty For the first time in Sunny Hills history, the ASB has added a freshman, sophomore and junior princess to the homecoming court. Find out about their thoughts of getting nominated on Fea- ture, page 8. Saturday’s “A Night in Athens” homecoming dance will be held for the first time in the remodeled gym. See Feature, page 9. 2 September 28, 2018 NEWS the accolade SAFE FROM STAINS Since the summer, girls restrooms n the 30s wing, 80s wing, next to Room 170 and in the Engineer- ing Pathways to Innovation and Change building have metallic ver- tical boxes from which users can select free Naturelle Maxi Pads or Naturelle Tampons. Free pads, tampons in 4 girls restrooms Fullerton Joint Union High School District installs metal box containing feminine hygiene products to comply with legislation CAMRYN PAK summer. According to the bill, the state News Editor The Fullerton Joint Union government funds these hygiene High School District sent a work- products by allocating funds to er to install pad and tampon dis- school districts throughout the *Names have been changed for pensers in the girls restrooms in state. Then, schools in need are confidentiality. the 30s wing, the 80s wing, next able to utilize these funds in order It was “that time of month” to Room 170 and in the Engineer- to provide their students with free again, and junior *Hannah Smith ing Pathways to Innovation and pads and tampons. -

2013 CA All-State Honor Choir Members (By School)

2013.All-StateStudentsBySchool 2013 CA All-State Honor Choir Members (by school) Last Name First Name School Choir Lin Alan Albany High School Mixed Ronningen Tom Albany High School Men Ford Miranda Alta Loma High School Women Rodriguez Stephanie Anaheim High School Women Hall Adam Arlington High School Men Jalique Anyssa Arlington High School Mixed Mata Daniel Arlington High School Men Maynes Spencer Arlington High School Men Cranor Kathryn Arnold O. Beckman High School Women Francisco Megan Arnold O. Beckman High School Women Kim Joseph Arnold O. Beckman High School Mixed Mehrdad Natasha Arnold O. Beckman High School Mixed Nguyen Austin Arnold O. Beckman High School Mixed Randall Jonathan Arnold O. Beckman High School Mixed Del Cid Raul Arroyo High School Mixed Mercado Benjamin Arroyo High School Men Braun Elsa Bakersfield Christian High School Women Guzman Brandon Bishop Amat Memorial High School Mixed Moriarty Kathleen Bishop Amat Memorial High School Women Darchuck Mackenzey Buchanan High School Women Murray Kenneshae Buchanan High School Women Sabangan Kenneth Buchanan High School Men Le Blanc Jesse Cabrillo High School Men Baskerville James Carlmont High School Mixed Coe Miles Carlmont High School Men Gowen Grace Carlmont High School Mixed Johnson Dario Carlmont High School Men Ong Laura Carlmont High School Women Hewett Emma Carmel High School Women Ingle Taylor Carmel High School Women Yoo Soorim Carmel High School Women Brown Emily Central Valley Christian School Women Mora Camila Central Valley Christian School Women Welsh -

SHHS Baseball Coach Challenges His Demotion

Property of Fullerton Public Library, Local History Room Community & Fine Arts Calendars p. 9-12 Fullerton Observer r Fullerton’s Only Local Independent Newspaper(printed on recycled paper) No.2407 October 15,1995 OCT OCT 15, 1995 FULLERTON OBSERVER PLEASE RETURN TO MAIN DESK FULLERTON PUBLIC LIBRARY ! 353 W. COMMONWEALTH A vE. , SHHS Baseball:phO I | CoachI A Q ph MB1I FULLERTON, CA 92632 I Challenges His Demotion By Ralph A. Kennedy Baseball Team. Your prompt response is fter serving 9 years as the pitching requested.” coach and last year as the head Burnett told this reporter that he believed coach of the Sunny Hills High the fact that he is partially disabled due to the A cerebral palsy which he has suffered since he School Junior Varsity Baseball Team, Joe Burnett is angry about being pushed out of a was about 3 years old was the determining job he believes he has been doing very well. factor in his demotion. “Apparently the Head Varsity Coach “I don’t think Coach Elliott ever was very Doug Elliott thought highly enough of my comfortable with my disability, and some of coaching to ask me to coach a combined the team’s parent boosters also were not varsity /junior' varsity baseball program this pleased with having a coach whose body was summer when he had to be away,” Burnett not completely whole,” Burnett explained. told the Observer when we interviewed him His answer from SHHS came from its in his home in La Habra. Principal Loring Davies, who explained that “After what I consider to be a successful “State law requires that ‘walk-on’ coaching summer, I was informed recently by one of positions must first be made available to my student players that I would not be the JV teachers employed by the District. -

CLASS SCHOOL SCORE Saturday, March 17, 2018 2018

Saturday, March 17, 2018 2018 Westminster High School @ Westminster High School in Westminster, California Winter Guard Association of Southern California (WGASC) CLASS SCHOOL SCORE JH AAA Brea Junior High School 46.80 JH AA Bellflower Middle School (JV) 69.11 JH AA Kraemer Middle School 64.36 JH AA Travis Ranch Middle School 60.13 JH AA Canyon Hills Middle School 56.99 JH AA Tuffree Middle School #1 56.30 JH A Bellflower Middle School (Varsity) 72.73 JH A Ross Middle School 70.49 JH A Alvarado Intermediate 69.16 JH A Lisa J. Mails Elementary School 64.39 HS AA Brea Olinda High School (Varsity) 68.58 HS AA Segerstrom High School 65.39 HS AA Santiago High School (GG) 61.98 HS AA Laguna Hills High School 58.49 HS AA Anaheim High School 57.76 HS AA Buena Park High School 55.15 HS AA Santa Fe High School #2 54.98 HS AA Lakewood High School 50.76 HS AA Fullerton Union High School 47.89 HS A - Round 1 California High School 73.50 HS A - Round 1 Tesoro High School 72.70 HS A - Round 1 Troy High School 70.88 HS A - Round 1 Westminster High School (JV) 69.98 HS A - Round 1 Sunny Hills High School #2 68.71 HS A - Round 1 Pacifica High School 67.39 HS A - Round 1 Santa Margarita Catholic High School 66.70 HS A - Round 2 Saddleback High School 63.84 HS A - Round 2 Western High School 76.71 HS A - Round 2 Duarte High School 74.20 HS A - Round 2 Bell High School 72.14 HS A - Round 2 Torrance High School 71.44 HS A - Round 2 Los Amigos High School 69.80 HS A - Round 2 Villa Park High School 68.93 HS A - Round 2 Santa Fe High School #1 68.48 Last Updated on 3/19/2018 at 12:00 PM Saturday, March 17, 2018 2018 Westminster High School @ Westminster High School in Westminster, California Winter Guard Association of Southern California (WGASC) CLASS SCHOOL SCORE SAAA - Round 1 San Marino High School 68.05 SAAA - Round 1 Glen A. -

SARC Report for Sunny Hills High School

Sunny Hills High School School Accountability Report Card Reported Using Data from the 2017—18 School Year California Department of Education By February 1 of each year, every school in California is required by state law to publish a School Accountability Report Card (SARC).The SARC contains information about the condition and performance of each California public school. Under the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) all local educational agencies (LEAs) are required to prepare a Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP), which describes how they intend to meet annual school-specific goals for all pupils, with specific activities to address state and local priorities. Additionally, data reported in an LCAP is to be consistent with data reported in the SARC. For more information about SARC requirements, see the California Department of Education (CDE) SARC web page at https://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/ac/sa/. For more information about the LCFF or LCAP, see the CDE LCFF web page at https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/aa/lc/. For additional information about the school, parents/guardians and community members should contact the school principal or the district office. DataQuest DataQuest is an online data tool located on the CDE DataQuest web page at https://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/ that contains additional information about this school and comparisons of the school to the district and the county. Specifically, DataQuest is a dynamic system that provides reports for accountability (e.g., test data, enrollment, high school graduates, dropouts, course enrollments, staffing, and data regarding English learners). Internet Access Internet access is available at public libraries and other locations that are publicly accessible (e.g., the California State Library). -

A Visit to My Motherland

Courtesy of the Local History Room, Fullerton Public Library COMMUNITY & ARTS CALENDAR Paqe 11-14 FULLERTON OBSERVER OBSERVER FULLERTON SEPTEMBER 1 2004 SEPTEMBER SAVING THE FOX THE NUFF REPORT The Historic Theatre Foundation would like to of Forum Identifies fer thanks to the following caring individuals, orga Campaign Issues nizations, and businesses who have made donations and pledges & challenge grants of over $250: • SI.650.000: City of Fullerton Redevelopment Agency; Neighbors United for Fullerton’s • $5.000: Mahsa Thomas and Associates - ReMax of sixth community forum delivered North Orange County; • $1.000: Mary Schade Wood; on its promise to delve into issues, • $25.000: Robert and Linda Weide; provide information, and offer op • $15.000: Mary Anne and Bradford Blaine (daughter of portunities for involvement in the Alice Ellen Chapman); coming Fullerton City Council elec • $10.000: “Fullerton Friends and Family” Votaw Data tion. Systems; Pam and Bob Clark, Jr.; Marilyn and Bob Three candidates for City Coun Clark, Sr.; Sharon and Councilmember Shawn Nelson cil - Doug Chaffee, Rex Pritchard • $5.000 - $9.999: Gloria Winkelmann, in memory of and Sharon Quirk - and more than Robert Winkelmann, Sr.; International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees - Local 504; Elizabeth 40 residents from Chapman Bowman (daughter of Alice Ellen Chapman); “We all sections of the Christiana S. Graham; Todd Huffman; The Douglas and city attended. Par Melissa Jones Family; Harold and Shirley Muckenthaler; need ticipants moved Cindy and Paul Sumner into small groups • $1.000 - 4.999: The children of Raymond Elementary a well to discuss those School; Catherine Baden and Nicholas Derr, in memory challenges that had of Nancy T. -

8.27.21-ISSUE-1.Pdf

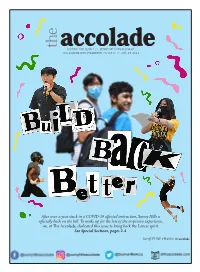

the accolade VOLUME LXII, ISSUE I // SUNNY HILLS HIGH SCHOOL 1801 LANCER WAY, FULLERTON, CA 92833 // AUG. 27, 2021 A!er over a year stuck in a COVID-19 a"ected instruction, Sunny Hills is o#cially back on the hill. To make up for the loss of the in-person experience, we, at !e Accolade, dedicated this issue to bring back the Lancer spirit. See Special Sections, pages 2-4. JACQUELINE CHANG | theaccolade August 27, 2021 2 !"#$%! "#$%!"&''&(! the accolade How to survive Sunny Hills 101 Never panic-run to your next class when the #rst bell rings. Avoid the quad bathroom at all costs. !e quad is for seniors only. !ese are the three pieces of krishna!aker advice my older Special Sections Editor cousin, a Sunny Hills alum- ni, gave me the day before I started high school. Being an impressionable student, I accepted them completely without question. However, now, three years later, I realize that the most important things I learned as a Sunny Hills student came MICHELLE SHEEN | theaccolade from trial and error and many mistakes BRAINSTORM SESSION: AVID teacher Lindsay Safe addresses students in the PAC on May 28 during the student along the way. feedback meeting, encouraging them to come up with fresh ideas for the 2021-2022 school year. A few students from all Whether it be #nding the best way the departments across campus were invited to join Safe and principal Allen Whitten in rebuilding school spirit. to study for Advanced Placement exams, learning to time your bathroom breaks to avoid the herd of students or successfully surviving #nals season, the Back on the Hill: A fresh start most helpful tip I can possibly give is At the end of the 2020-2021 sized the need to provide more hosted the back-to-school around the topic of being rein- to learn through experience. -

Council Takes Another Shot in Attempt to Kill $15 Million for Coyote Hills

COMMUNITY Fullerton bsCeALErNDAvR Peage 1r 3-15 O EAR FULLERTON’S ONLY INDEPENDENT NEWS • Est.1978 (printed on 20% recycled paper) • Y 40 #3 • MID FEBRUARY 2018 Submissions: [email protected] • Contact: (714) 525-6402 • Read Online at : www.fullertonobserver.com Officers Fired After Kelly Thomas Death - Sue City to Get Jobs Back by Jesse La Tour Two former Fullerton police officers who were fired over the beating/death of local homeless man Kelly Thomas have sued the city of Fullerton to get their jobs back, plus retroactive lost pay. The officers are Jay Cicinelli and Joseph Wolfe, both of whom were charged by the Orange County District Attorney with excessive force and involuntary manslaughter in 2012 over the much- publicized beating and death of Kelly Thomas. Both officers were fired over the incident. Cicinelli, along with officer Manuel Ramos, went to trial in 2014. Both were acquitted of all charges, including exces - sive force, prompting one of the largest protests in Fullerton history. For most Fullertonians, this was the end of the tragic saga of Kelly Thomas. HAPPY LUNAR NEW YEAR : The Fullerton Chinese Cultural Association hosted a Chinese New Year celebration But for Cicinelli and Wolfe (whose at Sunny Hills High School with dancing, food, calligraphy, and more on February 10th. PHOTO BY JESSE LA TOUR charges were dropped), the acquittal pro - vided grounds for suing the city. If, Union Pacific Park according to the jury, they had done noth - Council Takes Another Shot ing wrong, by that logic, they should not Mixed Use? have been fired. in Attempt to Kill $15 Million A Request for Qualifications inviting continued on page 5 development in the Truslow, Walnut, for Coyote Hills Valencia area, including Union Pacific 7 Park, will come before the city council at . -

PLACENTIA-YORBA LINDA UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT SUPERINTENDENT's COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL Monday, April 30, 2018 10:00 A.M. Di

PLACENTIA-YORBA LINDA UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT SUPERINTENDENT’S COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL Monday, April 30, 2018 10:00 a.m. District Education Center Board Room WELCOME The meeting was called to order at 10:05 a.m. by Deputy Superintendent Candy Plahy. Mrs. Plahy asked the representatives to take a few minutes to reflect and share with their table mates what was the best thing, in their opinion, that happened this year. ACCEPTANCE OF MINUTES The minutes of the March 5, 2018 meeting were accepted as submitted. GOOD NEWS REPORTS Board of Education Trustee Judi Carmona encouraged the representatives to attend the area music concerts for elementary, middle and high school feeder schools this month, as these are evenings filled with fantastic music performed by our students. Bryant Ranch Elementary students from the Little Diggers Garden Club started a farmers market on Fridays after school. The harvest includes beautiful flowers and vegetables grown organically and without toxic pesticides. Fourth grade students simulated the Gold Rush and a journey to California. Bryant Ranch celebrated three wonderful student performances of Seussical the Musical partnering with McCoy Rigby Conservatory of the Arts. Students are working hard to finish up a great year at Bryant Ranch! Community Advisory Council – Kathleen Callahan reminded representatives of the opportunity parents have to nominate a Special Education teacher of the year. Click here for nomination forms: CAC_form_English.pdf CAC_form_Spanish.pdf In addition, at the next meeting the council will be electing new board members. Esperanza High School shares that three hydration stations have been installed. The Anatomage table was revealed during the month of April. -

First Last High School Maya Martinez Alliance Environmental Science and Technology High School Samantha Guzman Alliance Marc &Am

first last High School Maya Martinez Alliance Environmental Science and Technology High School Samantha Guzman Alliance Marc & Eva Stern Math and Science School Melanie Mendez Animo Inglewood Charter High School Katelyn Martinez Animo Pat Brown Charter High School Sydney Tien Arcadia High School Tyler Yu Arcadia High School Shannon Wang Arnold O. Beckman High School Abra Kohl Brentwood School Madelyn Runcie Cabrillo Point Academy Hailey Bae California Academy of Mathematics and Science School Yaena Chun California Academy of Mathematics and Science School Lani Duong California School of the Arts – San Gabriel Valley Eileen Kang Cerritos High School Fatimah Faheem Cerritos High School Sydney Choi Cerritos High School Nicole Carter City Honors College Preparatory Charter School Hyeyeon Choi Clark Magnet High School Chloe Robinson Crean Lutheran High School Daniel Cho Crean Lutheran High School Justine Choi Crean Lutheran High School Lanyi Jin Crean Lutheran High School Maya Ochoa Crenshaw High School Morgan Kim Crescenta Valley High School Amelia Kamin Culver City High School Anna Martinez Culver City High School Lauryn Kinsella Culver City High School Mingus Schoffman Culver City High School Serena Lara-Greenberg Culver City High School Tobey Greenberg Culver City High School Elaine Moon Cypress High School Inseo Hong Cypress High School Leonard Lee Cypress High School Saena Lee Cypress High School Tina Ta Cypress High School Arely Martin Da Vinci Design Julia Chung Da Vinci Design Sidney Talbert Da Vinci Design Raina Henty-Dodd Da Vinci Science Brandy Perez Diego Rivera Learning Complex Wesley Bulthuis Don Bosco Technical Institute Sahti Barrios Downtown Magnets High School Victoria Perez Downtown Magnets High School Mayra Renteria Dr. -

News from FJUHSD

News from FJUHSD REVISED Fullerton Joint Union High School District ■ 1051 West Bastanchury Road, Fullerton 92833 For Immediate Release For More Information Contact: Date: October 30, 2017 Todd Butcher, 714-870-2818 FULLERTON JOINT UNION HIGH SCHOOL DISTRICT REOPENS THIRD KEY MEASURE I PROJECT, SUNNY HILLS HIGH SCHOOL GYMNASIUM REMODEL PROJECT The Fullerton Joint Union High School District (FJUHSD) held a public ribbon cutting ceremony for the gym modernization at Sunny Hills High School located at 1801 Warburton Way, Fullerton, on Tuesday, October 25, 2017 at 3:45 p.m. The Gymnasium is the third official project completed and delivered to the local community under the current $175 million, voter-approved Measure I bond program. The modernized gymnasium facility includes over 16,000 square feet of new flooring including a dance studio floor, a new main lobby including a new ticket booth and a new snack shop, and courts for Basketball and Volleyball, new ADA compliant restrooms, a new state of the art electronic scoreboard, and new bleachers that seat close to 962 people. Additional improvements include energy efficient lighting, HVAC systems, replacement of ceiling, new doors and hardware, new rolling shade systems, upgrade of major utility systems including electrical, sewer, water, fire alarm and data, and interior and exterior finishes. “This is the third of many outstanding projects that will serve our students for the next 50 years,” said Superintendent Scott Scambray of Fullerton Joint Union High School District. The next phase of high-priority Measure I projects the District is scheduled to kick off are the stadium modernization and new theater at La Habra High School; gym modernization at Troy High School; theater modernization at Fullerton Union High School; new stadium at Buena Park High School; and new gymnasium at Sonora High School.