Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Software Still Patentable?

Is Software Still Patentable? The last four years have posed significant hurdles to software patents; nevertheless they continue to be filed and allowed. By James J. DeCarlo and George Zalepa | August 20, 2018 | The Recorder Over the past four years, decisions by the Supreme Court and Federal Circuit, as interpreted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, have had a dramatic effect on software-related inventions. These decisions have focused primarily on what comprises patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and whether a patent’s specification adequately supports the claims. While uncertainty still exists, recent court decisions, coupled with sound prosecution strategies, can be used to bolster a practitioner’s arguments before the USPTO and courts. In Alice v. CLS Bank (2014), the Supreme Court applied the now familiar “two-part test” first laid out in Mayo v. Prometheus (2012). Under this test, a claim is first analyzed to determine if it is “directed to” an abstract idea. If so, the claim is then analyzed to determine whether it recites “significantly more” than the identified abstract idea or just “routine and conventional” elements. This test was (and is) routinely applied to software claims, and the pendulum of patentability for software inventions post-Alice swung firmly towards ineligibility. Nearly all decisions by the Federal Circuit in the immediate aftermath of Alice found claims ineligible. Similarly, the USPTO’s allowance rate in software-related art units plummeted, and many allowed but not yet issued applications were withdrawn by the USPTO. While many cases are representative of this period, the decision in Electric Power Group v. -

Does Strict Territoriality Toll the End of Software Patents?

NOTES DOES STRICT TERRITORIALITY TOLL THE END OF SOFTWARE PATENTS? James Ernstmeyer* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1267 I. UNITED STATES PROTECTION FOR INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IN SOFTWARE ........................................................................ 1269 A. Defining Software ...................................................................... 1269 B. Copyright Protection for Software ............................................ 1270 C. Patent Protection for Software .................................................. 1272 D. The Backlash Against Intellectual Property Rights in Software ..................................................................................... 1274 E. In re Bilski Turns Back the Clock .............................................. 1278 II. UNITED STATES SOFTWARE PATENTS IN CROSS-BORDER TRADE .... 1280 A. Global Economic Stakes in United States Software Patents ..... 1280 B. Congressional Protection of Patents in Cross-Border Trade ......................................................................................... 1281 C. Extraterritoriality Concerns in Applying § 271(f) to Software Patents ........................................................................ 1283 III. DO PATENTS PROTECT SOFTWARE? – WOULD COPYRIGHTS DO BETTER? ............................................................................................ 1287 A. Effects of the Microsoft v. AT&T Loophole .............................. 1287 B. Combining -

There Is No Such Thing As a Software Patent

There is no such thing as a software patent 1 Kim Rubin BSEE/CS 45 years technology experience 4 startups 100+ inventions Patent Agent Author Taught computer security Book shelf for patents 2 {picture of file cabinets here} 3 There is no such thing as a software patent 4 7.5 5 7.4 6 7.3 7 There is no such thing as a software patent. There is no such thing as a rubber patent. There is no such thing as a steel patent. There is no such thing as an electricity patent. 8 There is only ... a patent. 9 pro se en banc said embodiment 10 Czapinski v. St. Francis Hosp., Inc., 2000 WI 80, ¶ 19, 236 Wis. 2d 316, 613 N.W.2d 120. v. The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), ch. 675, 52 Stat. 1040, as amended, 21 U.S.C. § 301 et seq., iSee 21 U.S.C. § 355(a); Eli Lilly & Co. v. Medtronic, Inc., 496 U.S. 661, 665—666, 674 (1990). 11 Article I, Section 8 8. “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Inventors the exclusive Right to their Discoveries.” 12 Article I, Section 8 8. “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Inventors the exclusive Right to their Discoveries … except for software.” 13 Jefferson, Congress, SCOTUS and MPEP 3. “The Act embodied Jefferson’s philosophy that ‘ingenuity should receive a liberal encouragement.’ 5 Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 75-76 Washington ed. 1871). -

Prior Art Searches in Software Patents – Issues Faced

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights Vol 23, November 2018, pp 243-249 Prior Art searches in Software Patents – Issues Faced Shabib Ahmed Shaikh, Alok Khode and Nishad Deshpande,† CSIR Unit for Research and Development of Information Products, Tapovan, S.No. 113 & 114, NCL Estate, Pashan Road, Pune - 411 008, Maharashtra, India Received: 15 November 2017; accepted: 24 November 2018 Prior-art-search is a critical activity carried out by intellectual property professionals. It is usually performed based on known source of literature to ascertain novelty in a said invention. Prior-art-searches are also carried out for invalidating a patent, knowing state of the art, freedom to operate studies etc. In many technological domains such as chemistry, mechanical etc., prior art search is easy as compared to domain such as software. In software domain, prior-art can prove to be a complex and tedious process relying heavily on non-patent literature which acts as a pointer to the current technological trends rather than patent documents. This paper tries to highlight the issues faced by patent professionals while performing prior-art search in the field of software patents. Keywords: Patents, Software patents, World Intellectual Property Organisation, Prior art, Search Issues A patent is a form of intellectual property. It provides The identification of the relevant prior art, comprising exclusionary rights granted by national IP office to an of existing patents and scientific or non-patent inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time literature is important as it has bearing on the quality in exchange for public disclosure of an invention. -

Google Inc. in Response to the PTO's Request for Comments on the Partnership for Enhancement of Quality of Software-Related Patents, Docket No

From: Suzanne Michel Sent: Monday, April 15, 2013 8:40 PM To: SoftwareRoundtable2013 Subject: Submission of Google Inc Please find attached the submission of Google Inc. in response to the PTO's request for comments on the partnership for enhancement of quality of software-related patents, Docket No. PTO-P-2012-0052. If possible, please send an acknowledgment of receipt of the submission. Thank you very much, Suzanne Michel -- Suzanne Michel Senior Patent Counsel, Google [email protected] 202 677- | | | 5398 Before the United States Patent and Trademark Office Alexandria, VA 22313 In re: ) ) Docket No. PTO-P-2012-0052 Request for Comments and Notice ) of Roundtable Events for ) Partnership for Enhancement of ) Quality of Software-Related ) Patents ) ) COMMENTS OF GOOGLE INC. Daryl L. Joseffer Suzanne Michel KING & SPALDING LLP GOOGLE INC. 1700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW 1101 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 737-0500 (650) 253-0000 Adam M. Conrad KING & SPALDING LLP 100 N Tryon Street, Suite 3900 Charlotte, NC 28202 (704) 503-2600 April 15, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................1 PART II: THE PTO SHOULD APPLY SECTION 112(F) TO MORE PATENTS THAT CLAIM SOFTWARE-IMPLEMENTED INVENTIONS ...........................3 A. Section 112(f) Permits The Use Of Functional Claim Elements Only When The Specification Discloses Sufficient Structure To Limit The Claim To The Applicant’s Actual Invention. ...............................3 1. As A Matter Of Policy And Precedent, Patent Law Has Never Permitted Pure Functional Claiming. .......................................3 2. Congress Enacted Section 112(f) To Permit Functional Claiming Accompanied By Sufficient Disclosures. -

Committee on Development and Intellectual Property

E CDIP/13/10 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH DATE: MARCH 27, 2014 Committee on Development and Intellectual Property Thirteenth Session Geneva, May 19 to 23, 2014 PATENT-RELATED FLEXIBILITIES IN THE MULTILATERAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND THEIR LEGISLATIVE IMPLEMENTATION AT THE NATIONAL AND REGIONAL LEVELS - PART III prepared by the Secretariat 1. In the context of the discussions on Development Agenda Recommendation 14, Member States, at the eleventh session of the Committee on Development and Intellectual Property (CDIP) held from May 13 to 17, 2013, in Geneva, requested the International Bureau of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to prepare a document that covers two new patent-related flexibilities. 2. The present document addresses the requested two additional patent-related flexibilities. 3. The CDIP is invited to take note of the contents of this document and its Annexes. CDIP/13/10 page 2 Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………...…….….. 3 II. THE SCOPE OF THE EXCLUSION FROM PATENTABILITY OF PLANTS..…….…….…4 A. Introduction……..……………………………………………………………………….….4 B. The international legal framework………………………………………………………. 6 C. National and Regional implementation………………………………………………… 7 a) Excluding plants from patent protection……………………………………........ 8 b) Excluding plant varieties from patent protection………………………………... 8 c) Excluding both plant and plant varieties from patent protection……...……….. 9 d) Allowing the patentability of plants and/or plant varieties……………………… 9 e) Excluding essentially biological processes for the production of plants…….. 10 III. FLEXIBILITIES IN RESPECT OF THE PATENTABILITY, OR EXCLUSION FROM PATENTABILITY, OF SOFTWARE-RELATED INVENTIONS………………………….…….…. 12 A. Introduction………………………………………………………………………….….…12 B. The International legal framework………………………………………………………13 C. National implementations……………………………………………………………….. 14 a) Explicit exclusion …………………………………………………………………. 14 b) Explicit inclusion…………………………………………………………………... 16 c) No specific provision……………………………………………………………… 16 D. -

How Electric Power Group Case Is Affecting Software Patents by Michael Kiklis (August 19, 2019)

This article was originally published by Law360 on August 19, 2019. How Electric Power Group Case Is Affecting Software Patents By Michael Kiklis (August 19, 2019) Many commentators predicted the end of software patents after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International decision. Software patent practitioners therefore applauded when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit stated in 2016’s Enfish LLC v. Microsoft Corp. decision that “claims directed to software, as opposed to hardware, are [not] inherently abstract.”[1] But soon thereafter, our optimism waned when the Federal Circuit in Electric Power Group LLC v. Alstom SA found that data gathering, analysis and display is an abstract idea, thus rendering many software inventions abstract.[2] In fact, the Federal Circuit is recently applying Electric Power Group more Michael Kiklis frequently and has even expanded its use to find that “entering, transmitting, locating, compressing, storing, and displaying data”[3] and “capturing and transmitting data from one device to another” are abstract ideas.[4] Many software inventions — such as artificial intelligence systems — gather data, analyze that data and perform some operation that usually includes displaying or transmitting the result. Electric Power Group and its progeny therefore pose a serious risk to software inventions, including even the most innovative ones. Knowing how to avoid Section 101 invalidity risk from these cases is therefore critical. This article provides strategies for doing so. The Problem With Being Abstract Alice holds that if a claim is directed to an abstract idea and it does not recite an inventive concept, the claim is ineligible under 35 U.S.C. -

Patenting Software Is Wrong

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 58 Issue 2 Article 7 2007 Manuscript: You Can't Patent Software: Patenting Software is Wrong Peter D. Junger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter D. Junger, Manuscript: You Can't Patent Software: Patenting Software is Wrong, 58 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 333 (2007) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol58/iss2/7 This Tribute is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. MANUSCRIPT* YOU CAN'T PATENT SOFTWARE: PATENTING SOFTWARE IS WRONG PeterD. Jungert INTRODUCTION Until the invention of programmable' digital computers around the time of World War II, no one had imagined-and probably no one could have imagined-that methods of solving mathematical . Editor'sNote: This article is the final known manuscript of Professor PeterJunger. We present this piece to you as a tribute to Professor Junger and for your own enjoyment. This piece was not, at the time of ProfessorJunger 's passing, submitted to any Law Review or legal journal.Accordingly, Case Western Reserve University Law Review is publishing this piece as it was last edited by Professor Junger, with the following exceptions: we have formatted the document for printing, and corrected obvious typographical errors. Footnotes have been updated to the best of our ability, but without Professor Junger's input, you may find some errors. -

Everlasting Software

NOTES EVERLASTING SOFTWARE Software patents are some of the most commonly litigated, and pre- liminary evidence shows that they are particularly prone to ambush litigation.1 The typical ambush litigation plaintiff obtains a broadly worded patent and alleges that it covers a wide range of technologies, some of which may not even have existed at the time of the patent.2 The odd results of ambush litigation have led some commentators to call for the elimination of software patents.3 Their concerns are best illustrated with a famous example, the case of Freeny’s patent. In 1985, Charles Freeny, Jr., a computer scientist, obtained U.S. Pat- ent No. 4,528,643 on a method of remote manufacturing of goods using intermodem communication over phone lines.4 Freeny realized that it was inefficient for stores to stock electronic merchandise that might never sell.5 Therefore, he disclosed and claimed the following solution: customers would use an “information manufacturing machine[]” (IMM) at a point of sale to order goods.6 The IMM would communicate via modem with a central machine located at a remote location and receive authorization to produce the good via an authorization code.7 The IMM would then record an electronic good, such as a song, on a mate- rial object, such as a cassette, that the customer could take home.8 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 John R. Allison et al., Patent Quality and Settlement Among Repeat Patent Litigants, 99 GEO. L.J. 677, 695–96 (2011). 2 See JAMES BESSEN & MICHAEL J. MEURER, PATENT FAILURE 66–67 (2008). 3 See, e.g., Pamela Samuelson, Benson Revisited: The Case Against Patent Protection for Al- gorithms and Other Computer Program-Related Inventions, 39 EMORY L.J. -

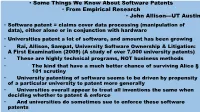

• Some Things We Know About Software Patents • from Empirical

• Some Things We Know About Software Patents • From Empirical Research • John Allison—UT Austin • Software patent = claims cover data processing (manipulation of data), either alone or in conjunction with hardware • Universities patent a lot of software, and amount has been growing • Rai, Allison, Sampat, University Software Ownership & Litigation: A First Examination (2009) (A study of over 7,000 university patents) • These are highly technical programs, NOT business methods • The kind that have a much better chance of surviving Alice § 101 scrutiny • University patenting of software seems to be driven by propensity of a particular university to patent more generally • Universities overall appear to treat all inventions the same when deciding whether to patent & enforce • And universities do sometimes sue to enforce these software patents Patents issued to the top 500 companies ranked by revenues from software and related services (Software Magazine—“The Software 500” each year 1998-2002—all patents owned by those firms in those years) Allison & Mann, The Disputed Value of Software Patents (2007) Includes both pure software firms and manufacturers that also patent software (20,000 non-IBM patents studied, estimates for 14,000 IBM patents) Only 30% of the firms owned any software patents at all Most depend on copyright and trade secret protection Manufacturers own the bulk of software patents The software patents have more total claims More independent claims More patent reference • Continued on next slide Patents issued to the top 500 -

Software Patent Law: United States and Europe Compared

SOFTWARE PATENT LAW: UNITED STATES AND EUROPE COMPARED Software is a global business. Patents are increasingly the protection of choice; as a consequence, international software patent laws are of growing importance to software vendors. This article focuses on European patent law and how it differs from United States law in regards to software technology. Statutes and relevant case law of both unions are discussed and compared, providing an introductory secondary source for scholars and practitioners. Introduction In the past, industrial countries had their own patent laws and offices. Those seeking protection in a specific country had to apply for a national patent and obey local laws. With increasing globalization, international agreements were made and organizations founded to reconcile regional differences: The 1883 Paris Convention1 was based on the principle of reciprocal national treatment and therefore dealt more with international comity than the unification of patent laws. The 1970 Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT)2 finally implemented international one-stop patents.3 Both treaties are administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).4 1 The Paris Convention for the Protection of Intellectual Property was enacted on March 20, 1883. It has been amended most recently in 1970. http://www.wipo.int/clea/docs/en/wo/wo020en.htm. 2 The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) was adopted on June 19, 1970 in Washington, D.C., and has been encoded in 35 U.S.C. §§ 351-76 (2000). 28 U.S.T. 7645. It has been modified most recently in October 2001. http://www.wipo.org/pct/en/index.html. 3 International one-stop patents—generally called PCTs after the enabling treaty—are patents that are recognized by all WIPO member countries (see n.4, infra). -

Bioinformatics: Patenting the Bridge Between Information Technology and the Life Sciences

93 BIOINFORMATICS: PATENTING THE BRIDGE BETWEEN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND THE LIFE SCIENCES CHARLES VORNDRAN, Ph.D.* AND ROBERT L. FLORENCE** INTRODUCTION Over the past two decades, advances in the fields of genomics and proteomics have enabled life scientists to amass an enormous amount of complex biological information. The ability to gather such information, however, has surpassed the ability and speed at which it can be interpreted. The growing field of bioinformatics holds great promise for making sense of this biological information through the development of new and innovative computational tools for the management of biological data. As with any developing field, the continued advancement and commercial viability of such innovations often depends on successful patent protection. This article , therefore, discusses the patentability of computer and software related inventions in this unique and evolving field. Part I begins by defining bioinformatics and bioinformatic -tools. A brief discussion of the main segments of the bioinformatics market is provided with examples from each segment. An explanation of how our bodies store and regulate the flow of genetic information is also provided in order to * Associate in the Atlanta office of Troutman Sanders LLP; J.D. 1997, Southern Methodist University; Ph.D. Biological Sciences 1995 concentrating on Cellular/Developmental/Molecular Biology, University of Texas at Austin; B.Sc. Zoology, 1988, University of Texas at Austin. The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of Troutman Sanders LLP. ** J.D. Candidate 2002, Franklin Pierce Law Center; B.Sc. Biology, 1998, University of Utah. Volume 42 — Number 1 94 IDEA — The Journal of Law and Technology demonstrate the usefulness of bioinformatics related inventions.