Autistic Representation in Television: a Preliminary Survey Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rumple Buttercup a Story of Bananas Belonging and Being Yourself by Matthew Gray Gubler ISBN 13: 9780525648444

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rumple Buttercup A Story of Bananas Belonging and Being Yourself by Matthew Gray Gubler ISBN 13: 9780525648444. Rumple Buttercup: A Story of Bananas, Belonging, and Being Yourself. Gubler, Matthew Gray. This specific ISBN edition is currently not available. The #1 New York Times bestseller written and illustrated by Criminal Minds actor/director, Matthew Gray Gubler. This charming and inspiring story is the perfect gift for kids (and grown-up kids) alike! Rumple Buttercup has five crooked teeth, three strands of hair, green skin, and his left foot is slightly bigger than his right. Join him and Candy Corn Carl (his imaginary friend made of trash) as they learn the joy of individuality as well as the magic of belonging. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. Matthew Gray Gubler is a storyteller from Las Vegas, Nevada, who directs, paints, writes, acts, and knows magic. He also loves to voice cartoon characters, look for ghosts, and wear soft pajamas. For more information, you can find him in a bathtub or at: matthewgraygubler.com Twitter: @GUBLERNATION Instagram: @gublergram. A Forbes Best Children's Book of the Year (so far) "Kids will love the weird, mythical and strangely cute character of Rumple Buttercup. It’s entertaining for all ages." — Forbes. Matthew Gray Gubler ID10T with Chris Hardwick. Matthew Gray Gubler (Criminal Minds, new book Rumple Buttercup: A Story of Bananas, Belonging, and Being Yourself) talks with Chris about how they handle busy schedules, the time he did @midnight and his love of magic. He also talks about directing, working on Criminal Minds for 15 years and his new children's book Rumple Buttercup: A Story of Bananas, Belongings, and Being Yourself! More Episodes © Chris Hardwick. -

Public Notices

Hawthorne Press Tribune The Weekly Newspaper of Hawthorne Herald Publications - Inglewood, Hawthorne, Lawndale, El Segundo, Torrance & Manhattan Beach Community Newspapers Since 1911 - Circulation 30,000 - Readership 60,000 (310) 322-1830 - May 3, 2018 Hawthorne High Volleys to Silver Inside This Issue Calendar of Events ............3 Certified & Licensed Professionals ......................7 Classifieds ...........................3 Entertainment .....................2 Hawthorne Happenings ...3 Food ......................................7 The Hawthorne High School boys volleyball team (pictured above) recently won the silver bracket at the Chadwick Tournament. The Cougars posted one-set playoff wins over both Marshall and Chadwick. Lawndale. .........................4,5 Photo: Hawthorne High School. Legals ................................4,6 Peter Burnett Team Presents to Wiseburn School Board Members By Duane Plank students and how they generated possible features.” Madsen added that the tentative As the 2017/18 school year enters its final solutions, with the students being allowed to grand opening of the El Segundo Aquatics months, the Wiseburn School Board met last “naturally solve” cognitive problems and not Center will be on Sept. 8, with the gym Thursday evening to witness a presentation rely on coaching from teachers to reach their tracking in a similar timeline and the soccer from Peter Burnett Elementary, helmed by final answers. One of the conclusions listed field completion slated afterwards. first-year principal Kim Jones. Jones was in the presentation: “Student confidence has Towards the end of the meeting, Director joined in the 40-plus-minute presentation soared because of becoming more account- of Psychological and Child Services Cathy Weekend by Cotsen math mentor Andrea Kwabasa, able for their learning.” Waller provided a quick update to the Board Cotsen fellow and fifth grade teacher Dorothy The impact of the school’s arts program on the progress made at the Wiseburn Child Forecast Sweeney, and arts instructor Tiffany Graham. -

Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading a Dissertation

"I Opened a Book and in I Strode": Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Ashley J. Barner April 2016 © 2016 Ashley J. Barner. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled "I Opened a Book and in I Strode": Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading by ASHLEY J. BARNER has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Robert Miklitsch Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BARNER, ASHLEY J., Ph.D., April 2016, English "I Opened a Book and in I Strode": Fanfiction and Imaginative Reading Director of Dissertation: Robert Miklitsch This dissertation studies imaginative reading and its relationship to fanfiction. Imaginative reading is a practice that involves engaging the imagination while reading, mentally constructing a picture of the characters and settings described in the text. Readers may imaginatively watch and listen to the narrated action, using imagination to recreate the characters’ sensations and emotions. To those who frequently read this way, imagining readers, the text can become, through the work of imagination, a play or film visualized or entered. The readers find themselves inside the world of the text, as if transported to foreign lands and foreign eras, as if they have been many different people, embodied in many different fictional characters. By engaging imaginatively and emotionally with the text, the readers can enter into the fictional world: the settings seem to them like locations they can visit, the many characters like roles they can inhabit or like real people with whom they can interact as imaginary friends and lovers. -

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

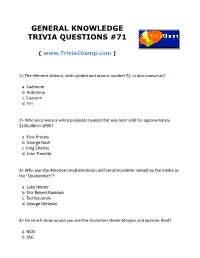

General Knowledge Trivia Questions #71

GENERAL KNOWLEDGE TRIVIA QUESTIONS #71 ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> The element stibium, with symbol and atomic number 51, is also known as? a. Cadmium b. Antimony c. Caesium d. Tin 2> Who once wore a white polyester tuxedo that was later sold for approximately $145,000 in 1995? a. Elvis Presley b. George Bush c. King Charles d. John Travolta 3> Who was the American mathematician and serial murderer named by the media as the "Unabomber"? a. Luke Helder b. Eric Robert Rudolph c. Ted Kaczynski d. George Metesky 4> On which show would you see the characters Derek Morgan and Spencer Reid? a. NCIS b. JAG c. MASH d. Criminal Minds 5> As of April 2014, who was the leader of Russia? a. Sergey Lavrov b. Boris Yeltsin c. Dmitry Medvedev d. Vladimir Putin 6> Whom does Mandy Patinkin play on the TV show "Homeland"? a. Jason Gideon b. Saul Berenson c. Jeffery Geiger d. Rube Sofer 7> Which city is home to the Maple Leaf's hockey team? a. Toronto b. Ottawa c. Calgary d. Vancouver 8> According to the Chinese Zodiac, what year is 2014? a. The snake b. The dragon c. The monkey d. The horse 9> According to the Guinness Book of World Records (2014), which nation holds the record for hosting the largest fireworks display? a. United States b. Japan c. China d. Dubai 10> Which politician was caught fooling around on a boat ironically named "The Monkey Business" in 1987? a. Brock Adams b. Gerry Studds c. Gary Hart d. Bill Clinton 11> Which chocolate bar shares its old slogan "Gimme a Break" with the name of a 1980s TV sitcom? a. -

Human Profiling: a Socio-Psycho Analysis of Humans

Human Profiling: A Socio-Psycho Analysis of Humans By Jenny Hwang Jenny Hwang graduated from Lone Star College in Spring 2017 as an Honors College Chancellor's Fellow, earning an Honors Associates of Science degree, and has been offered a scholarship from Hofstra University to study neuroscience. Her essay was the product of an honors learning community, which combined English Composition I and General Psychology, and earned her a presentation opportunity at the Fall 2016 Undergraduate Research Day at LSC-North Harris. Her research has also taken her to the Great Plains Honors Council (GPHC) Conference in Beaumont, Texas, and the National Collegiate Undergraduate Research (NCUR) Conference in Memphis, Tennessee in Spring 2017 as a representative of Lone Star College. While at LSC-NH, Jenny has been active in the Honors College Student Organization, Psi-Beta Honors Society, as well as a member of Phi Theta Kappa. This past year, she was named Student Life's "Outstanding Leader of the Year." A graduate of Aldine High School, Jenny has worked hard to improve as a writer and a speaker, and she places great emphasis on communications skills as a key to her success as a student with many cross-disciplinary interests. --English Professor Brian Kyser Introduction In the television show Criminal Minds, Dr. Spencer Reid and SSA (Supervisory Special Agent) Aaron Hotchner utilize criminal profiling to identify a suspect for "stabbing and burying a young boy to death by analyzing the gruesome crime scene photos" (Ryan 1). Criminal profiling is a tool used for criminal investigative analysts, or C.I analysts, to identify and apprehend subjects based on the way they commit the crime. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Boys & Girls & God: Essays Alaina Janelle Symanovich Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BOYS & GIRLS & GOD: ESSAYS By ALAINA JANELLE SYMANOVICH A Thesis submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2018 Alaina Janelle Symanovich defended this thesis on March 19, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Elizabeth Stuckey-French Professor Directing Thesis John Ribó Committee Member Bob Shacochis Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Chloe iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Versions of “The Girls We Love” appeared in Fogged Clarity and Ginosko Literary Review 17 “Faulty Hearts” appeared in Hawai’i Review 83 “The Dark Space” appeared as “Ready, Set, Go” in Entropy in September 2016 “Birds of Venus” appeared as “Venus Retrograde” in Little Patuxent Review 19 “Blood, Water, Sin” won the Winter 2017 Nonfiction Prize from Santa Ana River Review “The M Word” appeared in Fourth River 0.2 and won Best of the Net in 2016 “Ethereal Girls” appeared in Santa Ana River Review 2.1 “Holy Ground” appeared in storySouth 43 “In Transit” appeared in Quarter After Eight 23 “Me, Myself & Matthew Gray Gubler” appeared in Queen Mob’s Tea House in March 2017 “Shame, A Legacy” appeared as “Shame, A History” in Rubbertop Review 9 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

Cognitive Diversity in Composition Studies Crystal June Starkey Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-2-2013 A Cognitively Enabling Approach: Cognitive Diversity In Composition Studies Crystal June Starkey Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Starkey, Crystal June, "A Cognitively Enabling Approach: Cognitive Diversity In Composition Studies" (2013). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 797. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. A COGNITIVELY ENABLING APPROACH: COGNITIVE DIVERSITY IN COMPOSITION STUDIES by CRYSTAL J. STARKEY Submitted to the Graduate School Of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2013 MAJOR: ENGLISH (Composition Studies) Approved By: ____________________________________ Advisor Date ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY CRYSTAL STARKEY 2013 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION For Professor Griff. For Stark. And, for Viv…of course. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank first and foremost my advisor, Dr. Jeff Pruchnic, at Wayne State University, without whose weekly advice, suggestions, interventions, and guidance this dissertation would never have been completed. A memorable moment for me was when Dr. P said “Hey…that sounds like quitter talk to me!” He was right, I was ready to quit, but he wouldn’t let me. I know, without a single doubt I would not have finished this PhD without Dr. Pruchnic’s encouragement, humor, flexibility, support, and uncanny knack for always finding creative ways to email and talk when I needed to, regardless of the day or time. -

CELEBRITIES SCHEDULED to ATTEND (Appearance of Celebrities Subject to Change)

Festival of Arts / Pageant of the Masters Celebrity Benefit Event August 25, 2018 CELEBRITIES SCHEDULED TO ATTEND (Appearance of Celebrities Subject to Change) Sarah Drew (Host) – Drew is best known for her roles as Dr. April Kepner on ABC's GREY’S ANATOMY, Hannah Rogers on WB's EVERWOOD, and the voice of Stacy Rowe on MTV's DARIA. Other television credits include SUPERNATURAL, GLEE, MAD MEN, IN PLAIN SIGHT, CASTLE, PRIVATE PRACTICE, and MEDIUM. Drew most recently starred as Cagney in the CBS pilot reboot of CAGNEY AND LACEY. Film credits include MOMS’ NIGHT OUT, TUG, FRONT OF THE CLASS, REINVENTING THE WHEELERS, AMERICAN PASTIME, THE BAXTER and RADIO. Steve Tyrell (Performer) – Ever since his glorious surprise version of “The Way You Look Tonight” in the 1991 film FATHER OF THE BRIDE, Tyrell has been setting A New Standard (the title of his 1999 debut album) for interpreting the Great American Songbook. Nine of Tyrell's own albums have reached top- five status on Billboard's Jazz charts, with his most recent "A Song For You" hitting #1. He continually works to reinvent the American Standards Songbook and connect classic tunes to a modern audience, performing extensively with his band and with orchestras across the country and around the world-from the Hollywood Bowl to Carnegie Hall to Buckingham Palace. James Callis – He is an English born actor best known for starring role of “Dr. Gaius Baltar” in the Syfy series BATTLESTAR GALACTICA and films BRIDGET JONES’S DIARY and AUSTENLAND with Keri Russell. He has also appeared in the television series EUREKA, FLASHFORWARD, ARROW and 12 MONKEYS and starred in the tv movie MERLIN AND THE BOOK OF BEASTS. -

Autism Spectrum Disorder in Popular Media: Storied Reflections of Societal Views

Autism Spectrum Disorder in Popular Media: Storied Reflections of Societal Views Christina Belcher Redeemer University College Kimberly Maich Brock University Abstract This article explores how storied representations of characters with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are typified in a world that is increasingly influenced by popular media. Twenty commercially published children’s picture books, popular novels, mainstream television programs, and popular movies from 2006-2012 were selected using purposive, maximum variation sampling and analyzed through Krippendorff’s six-step approach to social content analysis. From this 20-unit sample, results show that television characters with ASD tend to be portrayed as intellectually stimulating geniuses who make us aspire to be like them; movies tend to show those with ASD as heroes, conquering seemingly impossible odds; novels tend to present ASD in a complex, authentic context of family and community, rife with everyday problems; picture books appear to be moving towards a clinical presentation of ASD. Common cross- categorical themes portray scientific, clinical, and/or savant-like traits that tend to glamourize challenges inherent to ASD. Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, popular media, perceptions, societal views Christina Belcher (Ph.D., O.C.T.) is a Professor in the Department of Education at Redeemer University College. Her research interests include higher education, worldview, literacy, and technology. E-mail: [email protected] Kimberly Maich (Ph.D., O.C.T.) teaches special education in the Department of Teacher Education at Brock University, and is an affiliated faculty member at Brock’s Centre for Applied Disability Studies. Her research focuses on special education, including Autism Spectrum Disorders, Applied Behaviour Analysis, social skills, assistive technology, and early childhood education. -

Shifts in Discourse and the Increasing Presence of Autism in Fictional Television Sierra Wolff University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2018 “Because He Is Different”: Shifts in Discourse and the Increasing Presence of Autism in Fictional Television Sierra Wolff University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wolff, Sierra, "“Because He Is Different”: Shifts in Discourse and the Increasing Presence of Autism in Fictional Television" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2142. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2142 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “BECAUSE HE IS DIFFERENT”: SHIFTS IN DISCOURSE AND THE INCREASING PRESENCE OF AUTISM IN FICTIONAL TELEVISION by Sierra M. Wolff A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2018 ABSTRACT “BECAUSE HE IS DIFFERENT”: SHIFTS IN DISCOURSE AND THE INCREASING PRESENCE OF AUTISM IN FICTIONAL TELEVISION by Sierra M. Wolff The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Elana Levine Characters with an autism spectrum disorder are not new to media, television in particular. What has recently changed is the willingness to put a label on a character who is on the spectrum. This thesis looks at 21 characters in television from 2007 to 2017 who are labeled or are generally perceived to be autistic. -

Film Stills: Background Briefing with Themes & Color on Program

Film stills: http://bit.ly/filmstill2018 Background briefing with themes & color on program: http://bit.ly/filmbriefing TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL® ANNOUNCES FEATURE FILM LINEUP FOR 17th EDITION, RUNNING APRIL 18-29 Liz Garbus’ THE FOURTH ESTATE to Close Festival; Drake Doremus’ ZOE selected as the Centerpiece Gala NEW YORK, NY (March 7, 2018) – The 17th annual Tribeca Film Festival, presented by AT&T, revealed its feature film lineup championing the discovery of emerging voices and celebrating new work from established filmmaking talent. To close the Festival, Tribeca will World Premiere The Fourth Estate, from Oscar®-nominated director Liz Garbus, which follows The New York Times’ coverage of the Trump administration’s first year. The Centerpiece Gala will be the World Premiere of Drake Doremus’ sci-fi romance Zoe starring Ewan McGregor, Léa Seydoux, Rashida Jones, and Theo James. The 2018 Tribeca Film Festival takes place April 18-29. The 2018 feature film program includes 96 films from 103 filmmakers. Of the 96 films, 46% of them are directed by women, the highest percentage in the Festival’s history. The lineup includes 74 World Premieres, 6 International Premieres, 9 North American Premieres, 3 U.S. Premieres, and 4 New York Premieres from 30 countries. This year’s program includes 46 first time filmmakers, with 18 directors returning to the Festival with their latest feature film projects. Tribeca’s 2018 slate was programmed from more than 8,789 total submissions. “We are proud to present a lineup that celebrates American diversity and welcomes new international voices in a time of cultural and social activism,” said Paula Weinstein, Executive Vice President of Tribeca Enterprises.