Prologue Australian Rules Football 101 It’S Not Rugby!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 Annual Report

2018-19 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Chairman's Report 2 Remote Projects 16 CEO's Report 3 Michael Long Learning & Leadership Centre 18 Directors 5 Facilities 19 Executive Team & Staff 7 Talent 20 Strategy 9 Commercial & Marketing 22 Community Football 10 Communications & Digital 26 Game Development 14 Financial Report 28 AFLNT 2018-19 Annual Report Ross Coburn CHAIRMAN'S REPORT Welcome to the 2019 AFLNT Annual Report. Thank you to the NT Government for their As Chairman I would like to take this continued belief and support of these opportunity to highlight some of the major games and to the AFL for recognising that items for the year. our game is truly an Australian-wide sport. It has certainly been a mixed year with We continue to grow our game with positive achievements in so many areas with participation growth (up 9%) and have some difficult decisions being made and achieved 100% growth in participants enacted. This in particular relates to the learning and being active in programs discontinuance of the Thunder NEAFL men’s provided through the MLLLC. In times and VFL women’s teams. This has been met when we all understand things are not at with varying opinions on the future their best throughout the Territory it is outcomes and benefits such a decision will pleasing to see that our great game of AFL bring. It is strongly believed that in tune with still ties us altogether with all Territorians the overall AFLNT Strategic Plan pathways, provided with the opportunities to this year's decisions will allow for greater participate in some shape or form. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction 3

Online Auction 3 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 Balance of collection including 1931-71 fixtures (7); Tony Locket AFL Goalkicking Estimate A$120 Record pair of badges; football cards (20); badges (7); phonecard; fridge magnets (2); videos (2); AFL Centenary beer coasters (2); 2009 invitation to lunch of new club in Reserve A$90 Sydney, mainly Fine condition. (40+) Lot 959 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 959 Balance of collection including Kennington Football Club blazer 'Olympic Premiers Estimate A$100 1956'; c.1998-2007 calendars (21); 1966 St.Kilda folk-art display with football cards (7) & Reserve A$75 Allan Jeans signature; photos (2) & footy card. (26 items) Lot 960 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 960 Collection including 'Mobil Football Photos 1964' [40] & 'Mobil Footy Photos 1965' [38/40] Estimate A$250 in albums; VFL Park badges (15); members season tickets for VFL Park (4), AFL (4) & Reserve A$190 Melbourne (9); books/magazines (3); 'Football Record' 2013 NAB Cup. (38 items) Lot 961 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 961 Balance of collection including newspapers/ephemera with Grand Final Souvenirs for Estimate A$100 1974 (2), 1985 & 1989; stamp booklets & covers; Member's season tickets for VFL Park (6), AFL (2) & Melbourne (2); autographs (14) with Gary Ablett Sr, Paul Roos & Paul Kelly; Reserve A$75 1973-2012 bendigo programmes (8); Grand Final rain ponchos. (100 approx) Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au 20 - 23 November 2020 Lot 962 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 962 1921 FOURTH AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CARNIVAL: Badge 'Australian Football Estimate A$300 Carnival/V/Perth 1921'. -

Indoor Cricket Rules

INDOOR CRICKET RULES THE GAME I. A game is played between two teams, each of a maximum of 8 players II. No team can play with less than 6 players III. The game consists of 2 x 16 over innings IV. The run deduction for a dismissal will be 5 runs V. Each player must bowl 2 overs and bat in a partnership for 4 overs VI. There are 4 partnerships per innings VII. A bowler must not bowl 2 consecutive overs VIII. Batters must change ends at the completion of each over ARRIVAL / LATE PLAYERS A. All teams are to be present at the court allocated for their match to do the toss 2 minutes prior to the scheduled commencement of their game. I Any team failing to arrive on time will forfeit the right to a toss. The non-offending team can choose to field first or wait until the offending team have 6 players present and bat first. II If both teams are late, the first team to have 6 players present automatically wins the toss. B. All forfeits will be declared at the discretion of the duty manager. I Individual players(s) arriving late may take part in the match providing their arrival is before the commencement of the 13 th over of the first innings. II Players who arrive late to field must wait until the end of the over in progress before entering the court. PLAYER SHORT / SUBSTITUTES Player Short a) If a team is 1 player short: When Batting: After 12 overs, the captain of the fielding side will nominate 1 player to bat again in the last 4 overs with the remaining batter. -

Football Officiating Manual

FOOTBALL OFFICIATING MANUAL 2020 HIGH SCHOOL SEASON TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE: OFFICIATING OVERVIEW .............................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 2 NATIONAL FEDERATION OFFICIALS CODE OF ETHICS ........................................... 3 PREREQUISITES AND PRINCIPLES OF GOOD OFFICIATING ................................. 4 PART TWO: OFFICIATING PHILOSOPHY ......................................................................... 6 WHEN IN QUESTION ............................................................................................................... 7 PHILOSOPHIES AND GUIDANCE ........................................................................................ 8 BLOCKING .................................................................................................................................... 8 A. Holding (OH / DH) ............................................................................................................. 8 B. Blocking Below the Waist (BBW) ..................................................................................... 8 CATCH / RECOVERY ................................................................................................................... 9 CLOCK MANAGEMENT ............................................................................................................. 9 A. Heat and Humidity Timeout ............................................................................................ -

Will American Football Ever Be Popular in the Rest of the World? by Mark Hauser , Correspondent

Will American Football Ever Be Popular in the Rest of the World? By Mark Hauser , Correspondent Will American football ever make it big outside of North America? Since watching American football (specifically the NFL) is my favorite sport to watch, it is hard for me to be neutral in this topic, but I will try my best. My guess is that the answer to this queson is yes, however, I think it will take a long me – perhaps as much as a cen‐ tury. Hence, there now seems to be two quesons to answer: 1) Why will it become popular? and 2) Why will it take so long? Here are some important things to consider: Reasons why football will catch on in Europe: Reasons why football will struggle in Europe: 1) It has a lot of acon and excing plays. 1) There is no tradion established in other countries. 2) It has a reasonable amount of scoring. 2) The rules are more complicated than most sports. 3) It is a great stadium and an even beer TV sport. 3) Similar sports are already popular in many major countries 4) It is a great for beng and “fantasy football” games. (such as Australian Rules Football and Rugby). 5) It has controlled violence. 4) It is a violent sport with many injuries. 6) It has a lot of strategy. 5) It is expensive to play because of the necessary equipment. 7) The Super Bowl is the world’s most watched single‐day 6) Many countries will resent having an American sport sporng event. -

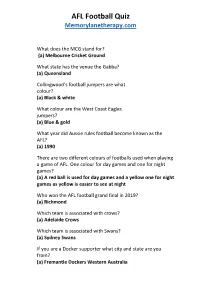

AFL Football Quiz Memorylanetherapy.Com

AFL Football Quiz Memorylanetherapy.com What does the MCG stand for? (a) Melbourne Cricket Ground What state has the venue the Gabba? (a) Queensland Collingwood’s football jumpers are what colour? (a) Black & white What colour are the West Coast Eagles jumpers? (a) Blue & gold What year did Aussie rules football become known as the AFL? (a) 1990 There are two different colours of footballs used when playing a game of AFL. One colour for day games and one for night games? (a) A red ball is used for day games and a yellow one for night games as yellow is easier to see at night Who won the AFL football grand final in 2019? (a) Richmond Which team is associated with crows? (a) Adelaide Crows Which team is associated with Swans? (a) Sydney Swans If you are a Docker supporter what city and state are you from? (a) Fremantle Dockers Western Australia If you are a Magpie what team do you belong to? (a) Collingwood What bird is associated with The West Coast? (a) West Coast Eagles How long is each quarter of play in the AFL? (a) 20 minutes but can fluctuate with stopping and play on Do AFL players wear boots or shoes when playing a game of football? (a) Football boots What shape is an AFL football? (a) Symmetric oval How many teams currently compete in the AFL? (a) 18 What medal is given each year to the fairest & best player in the league, voted by the umpires? (a) The Brownlow Medal What is the white line called around the edge of a football oval? (a) Boundary For more fun Activities for Seniors visit Memorylanetherapy.com . -

Indoor Cricket

Indoor Cricket RULES AND REGULATIONS Indoor Cricket is to be conducted under the Official Rules of Indoor Cricket which are sanctioned by Cricket Australia and the World Indoor Cricket Federation. The following local rules and regulations will apply. Team Requirements 1. The maximum number of players per team is 10, of which 8 can bat and 8 can bowl. 2. If a side is one player short: When batting: After 12 overs, the Captain of the fielding side will nominate one player to bat the last four overs with the remaining batter. When fielding: After 14 overs, the Captain of the batting side must choose two players (must be different players to the player that batted) to bowl the 15th and 16th overs. 3. If a side is two players short: When Batting: As above, except two players chosen will bat four overs each, being the last four overs. When fielding: After 12 overs, the Captain of the batting side must choose two players (must be different players to the players that batted) to bowl the last four overs. 4. If a side has less than 6 players, they must forfeit the game. Game Requirements 1. Games are to commence at 12.45pm. 2. Games will consist of 16 overs per team, 6 balls per over. 3. The batting team bats in pairs with each pair batting for four overs. Upon arrival at the batting crease the batting pair must inform the Umpire of their names. Batters continue batting for the whole four overs whether they are dismissed or not. -

Young American Sports Fans

Leggi e ascolta. Young American sports fans American football Americans began to play football at university in the 1870s. At the beginning the game was like rugby. Then, in 1882, Walter Camp, a player and coach, introduced some new rules and American Football was born. In fact, Walter Camp is sometimes called the Father of American Football. Today American football is the most popular sport in the USA. A match is only 60 minutes long, but it can take hours to complete because they always stop play. The season starts in September and ends in February. There are 11 players in a team and the ball looks like a rugby ball. ‘I play American football for my high school team. We play most Friday evenings. All our friends and family come to watch the games and there are hundreds of people at the stadium. The atmosphere is fantastic! High Five Level 3 . Culture D: The USA pp. 198 – 199 © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE In my free time I love watching professional football. My local team is the Green Bay Packers. It’s difficult to get a ticket for a game, but I watch them on TV.’ Ice hockey People don’t agree on the origins of ice hockey. Some people say that it’s a Native American game. Other people think that immigrants from Iceland invented ice hockey and that they brought the game to Canada in the 19th century. Either way, ice hockey as we know it today was first played at the beginning of the 20th century. The ice hockey season is from October to June. -

2017 TOYOTA AFL PREMIERSHIP SEASON ROUND 1 ROUND 7 ROUND 13 ROUND 19 Thursday, March 23 Friday, May 5 Thursday, June 15 Friday, July 28 Carlton Vs

2017 TOYOTA AFL PREMIERSHIP SEASON ROUND 1 ROUND 7 ROUND 13 ROUND 19 Thursday, March 23 Friday, May 5 Thursday, June 15 Friday, July 28 Carlton vs. Richmond (MCG) (N) St Kilda vs. GWS GIANTS (ES) (N) West Coast Eagles vs. Geelong Cats (DS) (N) Hawthorn vs. Sydney Swans (MCG) (N) Friday, March 24 Saturday, May 6 Friday, June 16 Saturday, July 29 Collingwood vs. Western Bulldogs (MCG) (N) North Melbourne vs. Adelaide Crows (BA) North Melbourne vs. St Kilda (ES) (N) North Melbourne vs. Melbourne (BA) Saturday, March 25 Collingwood vs. Carlton (MCG) Sydney Swans vs. Port Adelaide (SCG) (T) Saturday, June 17 GWS GIANTS vs. Fremantle (SP) St Kilda vs. Melbourne (ES) (T) Port Adelaide vs. West Coast Eagles (AO) (T) Richmond vs. Sydney Swans (MCG) Port Adelaide vs. St Kilda (AO) (T) Gold Coast SUNS vs. Geelong Cats (MS) (N) Gold Coast SUNS vs. Brisbane Lions (MS) (N) Port Adelaide vs. Brisbane Lions (AO) (T) Gold Coast SUNS vs. Richmond (MS) (N) Western Bulldogs vs. Richmond (ES) (N) Essendon vs. Hawthorn (MCG) (N) Gold Coast SUNS vs. Carlton (MS) (N) Carlton vs. Geelong Cats (ES) (N) Sunday, March 26 Sunday, May 7 Sunday, June 18 North Melbourne vs. West Coast Eagles (ES) Sydney Swans vs. Brisbane Lions (SCG) Sunday, July 30 Western Bulldogs vs. Melbourne (ES) Western Bulldogs vs. Essendon (ES) Adelaide Crows vs. GWS GIANTS (AO) Melbourne vs. Hawthorn (MCG) Byes: Adelaide Crows, Collingwood, Essendon, Fremantle vs. Geelong Cats (DS) (N) Fremantle vs. Essendon (DS) (T) Collingwood vs. Adelaide Crows (MCG) Fremantle, GWS GIANTS, Hawthorn West Coast Eagles vs. -

2019 VAFA Laws of the Game

2019 VAFA LAWS OF THE GAME UMPIRING OPERATIONS MANAGER • Haydn O’Connor • [email protected] • 0427 333 729 (Monday to Friday) • Umpire Feedback Form (VAFA Portal) ORDER OF EVENTS • Existing VAFA Laws to be changed in 2019 • New VAFA Laws & Interpretations to be introduced in 2019 • Laws not introduced in 2019 • Feedback/Questions EXISTING VAFA LAWS TO BE CHANGED IN 2019 50 METRE PENALTIES The VAFA will now impose 50 metre penalties in all sections in 2019 where a 25 metre penalty has been awarded previously. As per the VAFA Umpiring philosophy only MAJOR and OBVIOUS infringements will result in 50 metre penalties with examples in the interpretations video. HEAD COUNT – PLAYERS EXCEEDING PERMITTED NUMBER • Where a team has more than the permitted number of Players on the playing surface, the following shall apply; (a) A Field Umpire shall award a Free Kick to the captain or acting captain of the opposing Team, which shall be taken at the Centre Circle or where play was stopped, whichever is the greater penalty against the offending Team; (b) a 50 Metre Penalty shall then be imposed from the position where the Free Kick was awarded HEAD COUNT – CORRECT NUMBER • Where a count reveals that the opposing Team has the permitted number of Players on the Playing Surface, the following shall apply; (a) A field Umpire shall award a Free Kick to the captain or acting captain of the opposing Team, which shall be taken at the Centre Circle or where play was stopped, whichever is the greater penalty against the offending team; (b) a 50 Metre Penalty shall then be imposed from the position where the Free Kick was awarded. -

Unrivalled MCG.ORG.AU/HOSPITALITY Your Guide to Corporate Suites and Experiences in 2018/19

Premium Experiences Unrivalled MCG.ORG.AU/HOSPITALITY Your guide to corporate suites and experiences in 2018/19. An Australian icon The Melbourne Cricket Ground was built in 1853 and since then, has established a marvellous history that compares favourably with any of the greatest sporting arenas in the world. Fondly referred to as the ‘G, Australia’s favourite stadium has hosted Olympic and Commonwealth Games, is the birthplace of Test Cricket and the home of Australian Rules Football. Holding more than 80 events annually and attracting close to four million people, the MCG has hosted more than 100 Test matches (including the first in 1877) and is home to a blockbuster events calendar including the traditional Boxing Day Test and the AFL Grand Final. MCG EST. 1853 EST. MCG THE PINNACLE OF TEST CRICKET AND THE HOME OF AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL CORPORATE SUITE LEASING Many of Australia’s leading businesses choose to entertain their clients and staff in the unique and relaxed environment of their very own corporate suite at the iconic MCG. CORPORATE SUITE LEASING 2018/19 CORPORATE Designed to offer first-class amenities, personal service and an exclusive environment, an MCG corporate suite is the perfect setting to entertain, reward employees or enjoy an event with friends in capacities ranging from 10-20 guests. Corporate suite holders are guaranteed access to all AFL home and away matches scheduled at the MCG, AFL Finals series matches including the AFL Grand Final, and international cricket matches at the MCG, headlined by the renowned Boxing Day Test. You will also enjoy; - Two VIP underground car park passes - Company branding facing the ground - Two additional suite entry tickets to all events - Non-match day access for business meetings THE YEAR AWAITS There are plenty of exciting events to look forward to at the MCG in 2018, headlined by the AFL Grand Final, and the Boxing Day Test. -

Club and AFL Members Received Free Entry to NAB Challenge Matches and Ticket Prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series Were Held at 2013 Levels

COMMERCIAL OPERATIONS DARREN BIRCH GENERAL MANAGER Club and AFL members received free entry to NAB Challenge matches and ticket prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series were held at 2013 levels. eason 2015 was all about the with NAB and its continued support fans, with the AFL striving of the AFL’s talent pathway. to improve the affordability The AFL welcomed four new of attending matches and corporate partners in CrownBet, enhancing the fan experience Woolworths, McDonald’s and 2XU to at games. further strengthen the AFL’s ongoing SFor the first time in more than 10 development of commercial operations. years, AFL and club members received AFL club membership continued free general admission entry into NAB to break records by reaching a total of Challenge matches in which their team 836,136 members nationally, a growth was competing, while the price of base of 3.93 per cent on 2014. general admission tickets during the In season 2015, the Marketing and Toyota Premiership Season remained the Research Insights team moved within the same level as 2014. Commercial Operations team, ensuring PRIDE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA Fans attending the Toyota AFL Finals greater integration across membership, The Showdown rivalry between Eddie Betts’ Series and Grand Final were also greeted to ticketing and corporate partners. The Adelaide Crows and Port ticket prices at the same level as 2013, after a Research Insights team undertook more Adelaide continued in 2015, price freeze for the second consecutive year. than 60 projects, allowing fans, via the with the round 16 clash drawing a record crowd NAB AFL Auskick celebrated 20 years, ‘Fan Focus’ panel, to influence future of 53,518.