The an Ceathramh Language Learning Unit, Rogart, Sutherland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Item 6. Golspie Associated School Group Overview

Agenda Item 6 Report No SCC/11/20 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Area Committee Date: 05/11/2020 Report Title: Golspie Associated School Group Overview Report By: ECO Education 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report provides an update of key information in relation to the schools within the Golspie Associated School Group (ASG) and provides useful updated links to further information in relation to these schools. 1.2 The primary schools in this area serve around 322 pupils, with the secondary school serving 244 young people. ASG roll projections can be found at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/schoolrollforecasts 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to: scrutinise and not the content of the report. School Information Secondary – Link to Golspie High webpage Primary http://www.highland.gov.uk/directory/44/schools/search School Link to School Webpage Brora Primary School Brora Primary webpage Golspie Primary School Golspie Primary webpage Helmsdale Primary School Helmsdale Primary webpage Lairg Primary School Lairg Primary webpage Rogart Primary School Rogart Primary webpage Rosehall Primary School Rosehall Primary webpage © Denotes school part of a “cluster” management arrangement Date of Latest Link to Education School Published Scotland Pages Report Golspie High School Mar-19 Golspie High Inspection Brora Primary School Apr-10 Brora Primary Inspection Golspie Primary School Jun-17 Golspie Primary Inspection Helmsdale Primary School Jun-10 Helmsdale Primary Inspection Lairg Primary School Mar-20 Lairg Primary Inspection Rogart Primary -

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol. 22 : Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1 Vol. 22: Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh (East Sutherland & Caithness) Author: Kurt C. Duwe 2nd Edition January, 2012 Executive Summary This publication is part of a series dealing with local communities which were predominantly Gaelic- speaking at the end of the 19 th century. Based mainly (but not exclusively) on local population census information the reports strive to examine the state of the language through the ages from 1881 until to- day. The most relevant information is gathered comprehensively for the smallest geographical unit pos- sible and provided area by area – a very useful reference for people with interest in their own communi- ty. Furthermore the impact of recent developments in education (namely teaching in Gaelic medium and Gaelic as a second language) is analysed for primary school catchments. Gaelic once was the dominant means of conversation in East Sutherland and the western districts of Caithness. Since the end of the 19 th century the language was on a relentless decline caused both by offi- cial ignorance and the low self-confidence of its speakers. A century later Gaelic is only spoken by a very tiny minority of inhabitants, most of them born well before the Second World War. Signs for the future still look not promising. Gaelic is still being sidelined officially in the whole area. Local council- lors even object to bilingual road-signs. Educational provision is either derisory or non-existent. Only constant parental pressure has achieved the introduction of Gaelic medium provision in Thurso and Bonar Bridge. -

Sutherland Winter Maintenance Plan 2017-18

Agenda 6. Item Report SCC/23/17 No HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Sutherland County Committee Date: 29 November 2017 Report Title: Sutherland Winter Maintenance Plan 2017-18 Report By: Director of Community Services 1 Purpose/Executive Summary This report provides Members with information on winter maintenance preparations and arrangements for the 2017/18 winter period and invites the Committee to approve the Winter Maintenance Plans for Sutherland 2 Recommendations 2.1 Members are invited to approve the Winter Maintenance Plan for the Sutherland Area, which includes the priority road lists and maps presented in Appendices B & C. 3 Background 3.1 The Council’s Scheme of Delegation to Area Committees gives the Sutherland County Committee the power:- “to approve the winter maintenance plan within the strategy and budget allocated by Community Services Committee”. 3.2 Under Section 34 of the Roads (Scotland) Act 1984, a Roads Authority shall take such steps as they consider reasonable to prevent snow and ice endangering the safe passage of pedestrians and vehicles over public roads. 3.3 The Transport, Environmental and Community Service Committee agreed a number of enhancements to the winter maintenance service at its meeting on 16 May 2013 (Report TEC-41-13). These enhancements were included in the revised Winter Maintenance Policy approved on 19 September 2013 (Report TEC-67-13). Community Services Committee reviewed the winter Maintenance Policy on 28 April 2016 (Report COM23/16) which benchmarked winter maintenance against other Scottish Local Authorities. On the 28 April 2016 the Community Services Committee noted that 10% of the gritter fleet could start one hour earlier at 5 am to aid treatment of roads in advance of commuter traffic as well as aiding service bus/school transport routes in urban areas, on a discretionary basis based on specific hazards such as heavy ice or snow. -

The Scottish Highlanders and the Land Laws: John Stuart Blackie

The Scottish Highlanders and the Land Laws: An Historico-Economical Enquiry by John Stuart Blackie, F.R.S.E. Emeritus Professor of Greek in the University of Edinburgh London: Chapman and Hall Limited 1885 CHAPTER I. The Scottish Highlanders. “The Highlands of Scotland,” said that grand specimen of the Celto-Scandinavian race, the late Dr. Norman Macleod, “ like many greater things in the world, may be said to be well known, and yet unknown.”1 The Highlands indeed is a peculiar country, and the Highlanders, like the ancient Jews, a peculiar people; and like the Jews also in certain quarters a despised people, though we owe our religion to the Hebrews, and not the least part of our national glory arid European prestige to the Celts of the Scottish Highlands. This ignorance and misprision arose from several causes; primarily, and at first principally, from the remoteness of the situation in days when distances were not counted by steam, and when the country, now perhaps the most accessible of any mountainous district in Europe, was, like most parts of modern Greece, traversed only by rough pony-paths over the protruding bare bones of the mountain. In Dr. Johnson’s day, to have penetrated the Argyllshire Highlands as far west as the sacred settlement of St. Columba was accounted a notable adventure scarcely less worthy of record than the perilous passage of our great Scottish traveller Bruce from the Red Sea through the great Nubian Desert to the Nile; and the account of his visit to those unknown regions remains to this day a monument of his sturdy Saxon energy, likely to be read with increasing interest by a great army of summer perambulators long after his famous dictionary shall have been forgotten, or relegated as a curiosity to the back shelves of a philological library. -

Gordonbush Wind Farm Case Study

Gordonbush community funds The Gordonbush fund provides approx In addition, Gordonbush Wind Farm has About the proposed Working for a £200K each year for the community also provided £160,000 of funding towards council areas of Brora, Golspie, Helmsdale a new state of the art all-weather multi-use Gordonbush extension fairer Scotland and Rogart. Since 2011 it has granted over sports pitch in Golspie. £514,000 to community and charitable groups and projects in these areas. An application has been submitted to the Scottish SSE is also working hard to help make a fairer £200K average annual fund Government for a proposed 16 turbine extension Scotland. It does this by helping local communities to the south-west of the existing Gordonbush Wind to realise opportunities for growth at the local level total funds awarded since 2011 £514K Farm site. and by supporting national initiatives to encourage 136 projects funded since 2011 sustainable economic growth across Scotland. The proposed extension has been carefully 25 year project lifespan designed to minimise visibility from the surrounding As a responsible UK company, SSE wants to be as landscape, particularly Strath Brora, and also transparent as possible about the contribution it is £5.5M+ total funding 2011-2036 maximise the existing infrastructure on site. making to society. In 2014 SSE was the first FTSE Gordonbush 100 company to be awarded the fair tax mark. Brora Angling Club SSE held two public exhibitions in 2013 and 2015 Received £5,000 to purchase a new boat to gain feedback on the proposal from the Wind Farm community before submitting it’s application. -

Free Presbyterian Magazine

''-~~ '··· ..... _r'·.'~' Vol. XLVI.-No. 1. May, 1941. THE Free Presbyterian Magazine AND MONTHLY RECORD (Issued by a Oommittee oj the Free Presbyterian Synod.) "l'ho'U hast given a banner to them that fear Thee, that it may be displayed beoause of the truth. "-Ps. Ix. 4. CONTENTS. Page The Power of the Church 1 A Sermon ... 5 ~ The Giory of the Coming of the LonJ 12 The late John MacEwan, Lochgilphead 13 Letter to a Youth 15 Nadur an Duine 'na Staid Cheithir Fillte ... 16 The late Kenneth Macpherson, Porthenderson, Gairloch 19 Literary Notices 21 Notes and Comments 21 Church Notes 28 Acknowledgment of Donations 28 The Magazine 30 Printed by N. Adshead & Son, 34-36 Cadogan Street, Glasgow. Price 3~d Post free 4~d Annual Subscription 45 6d prepaid, post free. THE jfrtt ~rt1)b!'ttrian :maga?int and MONTHLY RECORD. VOL. XLVI. May, 1941. No. 1. The Power of the Church. IN almost every age there has been a diversity of opinion as to the power of the Church of Christ on earth. This diversity of opinion is brought very prominently to our notice in the history of the Church in our own land since the time of the Reformation. Romanists claim that the Church is above the III State and that the Pope has the right to depose Kings and remove governments, in virtue of his claim to be the head of the Church. Erastians maintain that the Church is the creature of the State, and that the power of discipline and government in the Church i is committed to the office-bearens of the Church by the civil magistrate. -

Abbie Is a Star Karter

War and wildlife on Abbie is a the Moray Firth star karter Active Outdoors Page 20 Page 4 AND WEEKLY JOURNAL FOR SUTHERLAND AND THE NORTH FOUNDED 1899 FRIDAY, APRIL 25, 2014 www.northern-times.co.uk £1 SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: 75p INSIDE THIS WEEK’S NORTHERN Fresh fight TIMES PETS over wind farm plan By Caroline McMorran reports the Tressady develop- either individually or cumu- [email protected] ment would be visible at all latively with other operational points of the compass within a developments.” OBJECTORS to the controver- 3km radius. But members of the coun- sial Tressady wind farm project Those against are concerned cil’s north planning committee are gearing up for a fresh fight. about the visual impact, noise went against planners’ recom- The plan to erect 13 tur- nuisance and effect on tour- mendation, and voted seven to Pip is Pet of Month bines, each 115 metres high, ism, among other issues. two against the development Page 19 to the north west of Rogart, Alastair Gilchrist, East following a site visit. was rejected earlier this year Langwell, objected to the origi- Councillors were swayed by by Highland Council’s north nal Tressady application. East Sutherland and Edderton planning committee He said: “We’re within a mile member Graham Phillips who ARTS But the power company from the nearest turbine to our had demanded a visit be made behind the project, Wind house. to the area before a decision Prospect Developments, are “When I look out my house was taken. now appealing that decision, just now I can see three tur- Councillor Phillips said he You don’t have to be it was officially confirmed this bines at Lairg. -

Fleetwood House, Muie, Rogart Sutherland Iv28

MACKENZIE & CORMACK SOLICITORS, ESTATE AGENTS & NOTARIES PUBLIC 20 TOWER STREET, TAIN, ROSS-SHIRE, IV19 1DZ TELEPHONE (01862) 892046 FAX (01862) 892715 Website: www.mackenzieandcormack.co.uk Email: [email protected] REPORT VALUATION BELOW£36,000 HOME FLEETWOOD HOUSE, MUIE, ROGART SUTHERLAND IV28 3UB FIXED PRICE £199,000 Fleetwood House is a unique architect designed property specifically created to an energy efficient ecological brief. Accomm: Ent Hall, Living/Dining/Sitting Room, Office, Kitchen/Diner, Utility Room, Bedroom, Bathroom, Mezzanine with Open-plan Bedroom/Sitting Room/Bathroom/Study, and Cloakroom. Solid wood flooring, wood burning stove, 2 LPG converted Morso stoves and the external appearance is finished with sympathetic wood cladding. Stylish layout with large open-plan split level main reception room. The first floor mezzanine also has an open-plan layout providing bedroom area, lounge area and bath all of which overlook the ground floor reception room. With uninterrupted panoramic views down Rogart Glen from Fleetwood’s elevated hilltop position. Viewing is essential to appreciate this stunning property. HSPC Ref: MK04/45895 NIGEL D JONES LLB (HONS) DIP LP NP IAIN MCINTOSH LLB (HONS) DIP LP NP View from Bedroom 1 The property benefits from solid fuel CH (partial under Bathroom: 2.30m x 1.45m floor) via a wood-burning stove in the living room and WC, wash hand basin and bath with electric Triton shower there are 2 LPG converted Morso squirrel stoves. High over. The bath area is fully tiled. Ladder radiator. performance double glazed windows and a high standard of insulation make it highly energy efficient. -

Dalreavoch-Sciberscross Strath Brora, Sutherland

Dalreavoch-Sciberscross Strath Brora, Sutherland Sheepfold in Strath Brora A Report on an Archaeological Walk-Over Survey Prepared for Scottish Woodlands Ltd Nick Lindsay B.Sc, Ph.D Tel: 01408 621338 (evenings) Sunnybrae Tel: 01408 635314 (daytime) West Clyne e-mail: [email protected] Brora Sutherland September 2009 KW9 6NH A9 Archaeology - Dalreavoch Bridge and Sciberscross, Strath Brora, Sutherland Contents 1.0 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................2 2.0 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................3 2.1 Background............................................................................................................................3 2.2 Objectives ..............................................................................................................................3 2.3 Methodology..........................................................................................................................3 2.4 Limitations.............................................................................................................................3 2.5 Setting....................................................................................................................................3 3.0 Results .......................................................................................................................................5 -

The Clyne Chronicle

The Clyne Chronicle The Magazine of Clyne Heritage Society £2.95 (FREE to members) | Nº.21 Wilkhouse archaeological excavation See Page 38! Includes: First-Time Archaeologist: My Take on the Wilkhouse Dig Janet French Nurse MacLeod's Babies Dr Nick Lindsay Sutherland Estate Petitions 1871 Dr Malcolm Bangor-Jones Lt E Alan Mackintosh, World War 1 Poet with Brora Connections Dr Donald Adamson The Capaldi's of Brora Story Morag L Sutherland …and more With great thanks to Cunningham’s of Brora and Cornucopia for continuing support. Scottish Charity No. SC028193 Contents Comment from the Chair 3 Chronicle News 4 Brora Heritage Centre: the Story of 2017 5 Nurse MacLeod’s Babies! 12 93rd Sutherland Highlanders 1799-1815: The Battle of New Orleans 13 Old Brora Post Cards 19 My Family Ties With Clyne 21 Sutherland Estate Petitions 1871 27 Lt E Alan Mackintosh, World War 1 Poet with Brora Connections 34 The Wilkhouse Excavations, near Kintradwell 38 First-Time Archaeologist: My Take on the Wilkhouse Dig 46 Clyne War Memorial: Centenary Tributes 51 Guided Walk Along the Drove Road from Clynekirkton to Oldtown, Gordonbush, Strath Brora 54 Veteran Remembers 58 The Capaldi's of Brora Story 60 Old Clyne School: The Way Forward 65 More Chronicle News 67 Society Board 2018-19 68 In Memoriam 69 Winter Series of Lectures: 2018-19 70 The Editor welcomes all contributions for future editions and feedback from readers, with the purposes of informing and entertaining readers and recording aspects of the life and the people of Clyne and around. Many thanks to CHS member, Tim Griffiths, for much appreciated technical assistance with the Chronicle and also to all contributors. -

Archaeological Evaluation

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Bringing the Past and Future Together Doune Strath Oykel, Sutherland Archaeological Evaluation 7 Duke Street Cromarty Ross-shire IV11 8YH Tel / Fax: 01381 600491 Mobile: 07834 693378 Email: [email protected] Web: www.hi-arch.co.uk Registered in Scotland no. 262144 Registered Office: 10 Knockbreck Street, Tain, Ross-shire IV19 1BJ VAT No. GB 838 7358 80 Independently Accredited for Health and Safety, Environment and Quality Control by UVDB Verify Land at Doune, Strath Oykel, Sutherland: Archaeological Evaluation April 2011 Doune Strath Oykel, Sutherland Archaeological Evaluation Report No. HAS110501 Site Code SYK11 Client W Ross OS Grid Ref NC 4451 0090 OASIS highland4-101448 HCAU / Planning Ref 10/03909/PIP Date / revised 05/07//2011 Author J Wood Summary Desk-based assessment and trial trenching evaluation were undertaken at Doune, Strath Oykel, Sutherland to establish the nature of a recorded archaeological feature which could be affected by the construction of a house. Archaeological evidence was discovered but its extent is limited and its nature is unclear. It is recommended that the archaeological area should either be preserved in situ, or recorded fully if removal is unavoidable. 2 Land at Doune, Strath Oykel, Sutherland: Archaeological Evaluation April 2011 Contents Location ......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. -

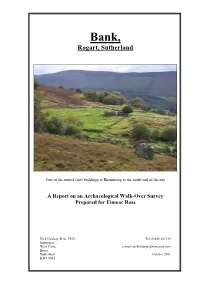

Rogart, Sutherland

Bank, Rogart, Sutherland One of the ruined croft buildings at Rhemusaig at the south end of the site A Report on an Archaeological Walk-Over Survey Prepared for Eimear Ross Nick Lindsay B.Sc, Ph.D Tel: 01408 621338 Sunnybrae West Clyne e-mail: [email protected] Brora Sutherland October 2011 KW9 6NH Bank, Rogart, Sutherland Contents 1.0 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................2 2.1 Background............................................................................................................................3 2.2 Objectives..............................................................................................................................3 2.3 Methodology..........................................................................................................................3 2.4 Limitations.............................................................................................................................3 2.5 Setting....................................................................................................................................3 3.0 Results .......................................................................................................................................5 3.1 Desk-Based Assessment........................................................................................................5 3.2 Field Survey.........................................................................................................................12