Guitar Music by Japanese Composers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X-Rated and Excessively Long: Ji-Amari in Hayashi Amari's Tanka

Portland State University PDXScholar World Languages and Literatures Faculty Publications and Presentations World Languages and Literatures 2018 X-Rated and Excessively Long: Ji-Amari in Hayashi Amari's Tanka Jon P. Holt Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/wll_fac Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Holt, J. (2018). X-Rated and Excessively Long: Ji-Amari in Hayashi Amari's Tanka. US-Japan Women's Journal, 53(53), 72-95. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Literatures Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. X-Rated and Excessively Long: Ji-Amari in Hayashi Amari's Tanka Jon Holt U.S.-Japan Women's Journal, Number 53, 2018, pp. 72-95 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jwj.2018.0003 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/709982 [ Access provided at 21 May 2020 18:31 GMT from Portland State University ] X-Rated and Excessively Long: Ji-Amari in Hayashi Amari’s Tanka Jon Holt As a fixed 31-syllable form of short poetry, Japan’s tanka is one of the world’s oldest forms of still-practiced poetry, with examples perhaps dating back to the fifth century. In the modern periods of Meiji (1868-1912) and Taishō (1912-1926), poets radically reformed the genre, expanding diction beyond millennium-old classical limits, thereby allowing poets to write not only about cherry blossoms and tragic love but also about things like steam trains and baseball games; although today many tanka poets in practicing circles still employ classical Japanese, many modern masters innovated the genre by skillfully blending in colloquial language. -

Tōru Takemitsu᾽S "Spherical Mirror:" the Influences of Shūzō Takiguchi and Fumio Hayasaka on His Early Music in Postwar Japan

Athens Journal of Humanities and Arts X Y Tōru Takemitsu᾽s "Spherical Mirror:" The Influences of Shūzō Takiguchi and Fumio Hayasaka on his Early Music in Postwar Japan Tomoko Deguchi The music of Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996) eludes understanding by traditional musical analytical approaches. In his earlier works, the musical language Takemitsu employed is influenced by Debussy, Webern, and particularly Messiaen; however, his music defies successful analyses by Western analytical methods, mainly to find an organizational force that unifies the composition as a whole. In this essay, I illuminate how his music was made to be "Japanese- sounding," even though Takemitsu clearly resisted association with, and was averse to, Japanese traditional culture and quality when he was younger. I do this by examining Takemitsu᾽s friendship with two individuals whom he met during his early age, who influenced Takemitsu at an internal level and helped form his most basic inner voice. The close friendship Takemitsu developed as a young composer with Shūzō Takiguchi (1903-1979), an avant-garde surrealist poet and also a mentor to many forward-looking artists, and Fumio Hayasaka (1914-1955), a fellow composer best known for his score to Akira Kurosawa᾽s film Rashōmon, is little known outside Japan. In this essay, I discuss the following issues: 1) how Takiguchi᾽s experimental ideas might have manifested themselves in Takemitsu᾽s early compositions; and 2) how Hayasaka᾽s mentorship, friendship, and ideals of the nature of Japanese concert music might have influenced Takemitsu᾽s early pieces. I analyze some earlier compositions by Takemitsu to discuss the influences on his music by his two mentors, whose attitudes seemingly had come from opposite spectrums. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Commemorative Concert the Suntory Music Award

Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Suntory Foundation for Arts ●Abbreviations picc Piccolo p-p Prepared piano S Soprano fl Flute org Organ Ms Mezzo-soprano A-fl Alto flute cemb Cembalo, Harpsichord A Alto fl.trv Flauto traverso, Baroque flute cimb Cimbalom T Tenor ob Oboe cel Celesta Br Baritone obd’a Oboe d’amore harm Harmonium Bs Bass e.hrn English horn, cor anglais ond.m Ondes Martenot b-sop Boy soprano cl Clarinet acc Accordion F-chor Female chorus B-cl Bass Clarinet E-k Electric Keyboard M-chor Male chorus fg Bassoon, Fagot synth Synthesizer Mix-chor Mixed chorus c.fg Contrabassoon, Contrafagot electro Electro acoustic music C-chor Children chorus rec Recorder mar Marimba n Narrator hrn Horn xylo Xylophone vo Vocal or Voice tp Trumpet vib Vibraphone cond Conductor tb Trombone h-b Handbell orch Orchestra sax Saxophone timp Timpani brass Brass ensemble euph Euphonium perc Percussion wind Wind ensemble tub Tuba hichi Hichiriki b. … Baroque … vn Violin ryu Ryuteki Elec… Electric… va Viola shaku Shakuhachi str. … String … vc Violoncello shino Shinobue ch. … Chamber… cb Contrabass shami Shamisen, Sangen ch-orch Chamber Orchestra viol Violone 17-gen Jushichi-gen-so …ens … Ensemble g Guitar 20-gen Niju-gen-so …tri … Trio hp Harp 25-gen Nijugo-gen-so …qu … Quartet banj Banjo …qt … Quintet mand Mandolin …ins … Instruments p Piano J-ins Japanese instruments ● Titles in italics : Works commissioned by the Suntory Foudation for Arts Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Awardees and concert details, commissioned works 1974 In Celebration of the 5thAnniversary of Torii Music Award Ⅰ Organ Committee of International Christian University 6 Aug. -

La Romanesca Monodies 1 Istanpitta Ghaetta (Anonymous, 14Th Century) 8’52” 2 Lo Vers Comenssa (Marcabru, Fl

La Romanesca Monodies 1 Istanpitta Ghaetta (anonymous, 14th century) 8’52” 2 Lo vers comenssa (Marcabru, fl. 1127-1150) 6’44” 3 Lo vers comens can vei del fau (Marcabru) 5’15” 4 Saltarello (anonymous, 14th century) 4’16” 5 L’autrier jost’ una sebissa (Marcabru) 5’04” 6 Bel m’es quant son li fruit madur (Marcabru) 9’15” 7 Istanpitta Palamento (anonymous, 14th century) 7’40” Cantigas de amigo (Martin Codax, 13th century) 8 Ondas do mar de Vigo 4’28” 9 Mandad’ ei comigo 3’58” 10 Miña irmana fremosa iredes comigo 3’15” 11 Ay Deus, se sab’ ora o meu amigo 3’30” 12 Quantas sabedes amar amigo 2’02” 13 Eno sagrado Vigo 3’07” 14 Ay ondas que eu vin ver 2’11” Hartley Newnham – voice, percussion Ruth Wilkinson – recorder, vielle, tenor viol Ros Bandt – recorder, flute, psaltery, rebec, percussion John Griffiths – lute, guitarra morisca Monodies La Romanesca P 1982 / 2005 Move Records expanded edition of Medieval Monodies – total playing time 70 minutes move.com.au he poet-musicians Marcabru and Uncompromising are his attacks on false of Lo vers comens can vei del fau, similarly Martin Codax occupy important lovers who debase the integrity of true love. derived from a later contrafactum version in Tplaces in the history of medieval Undisguised is his criticism of the excesses manuscript Paris, Bib. Nat. f. lat. 3719. secular song. Marcabru is the earliest southern of the nobility whom he served. Such is his Of much safer attribution, Bel m’es quant French troubadour whose music survives, and venom that one of his biographers comments son li fruit madur is the most sophisticated Martin Codax’s songs are the oldest relics of that “he scorns women and love”. -

The Trecento Lute

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Trecento Lute Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kh2f9kn Author Minamino, Hiroyuki Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Trecento Lute1 Hiroyuki Minamino ABSTRACT From the initial stage of its cultivation in Italy in the late thirteenth century, the lute was regarded as a noble instrument among various types of the trecento musical instruments, favored by both the upper-class amateurs and professional court giullari, participated in the ensemble of other bas instruments such as the fiddle or gittern, accompanied the singers, and provided music for the dancers. Indeed, its delicate sound was more suitable in the inner chambers of courts and the quiet gardens of bourgeois villas than in the uproarious battle fields and the busy streets of towns. KEYWORDS Lute, Trecento, Italy, Bas instrument, Giullari any studies on the origin of the lute begin with ancient Mesopota- mian, Egyptian, Greek, or Roman musical instruments that carry a fingerboard (either long or short) over which various numbers M 2 of strings stretch. The Arabic ud, first widely introduced into Europe by the Moors during their conquest of Spain in the eighth century, has been suggest- ed to be the direct ancestor of the lute. If this is the case, not much is known about when, where, and how the European lute evolved from the ud. The presence of Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula and their cultivation of musical instruments during the middle ages suggest that a variety of instruments were made by Arab craftsmen in Spain. -

Simon Powis, Guitar (Australia) New Opportunities for a Twenty-First Century Guitarist 6:00 - 7:15 P.M

The 16th Annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival June 3 - 5, 2016 Vieaux, USA SoloDuo, Italy Poláčková, Czech Republic Gallén, Spain De Jonge, Canada North, England Powis, Australia Davin, USA Beattie, Canada Presented by UITARS NTERNATIONAL G I in cooperation with the GUITARSINT.COM CLEVELAND, OHIO USA 216-752-7502 Grey Fannel HAUTE COUTURE Fait Main en France • Hand Made in France www.bamcases.com Welcome Welcome to the sixteenth annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival. In pre- senting this event it has been my honor to work closely with Jason Vieaux, 2015 Grammy Award Winner and Cleveland Institute of Music Guitar Department Head; Colin Davin, recently appointed to the Cleveland Institute of Music’s Conservatory Guitar Faculty; and Tom Poore, a highly devoted guitar teacher and superb writer. Our reasons for presenting this Festival are fivefold: (1) to help increase the awareness and respect due artists whose exemplary work has enhanced our lives and the lives of others; (2) to entertain; (3) to educate; (4) to encourage deeper thought and discussion about how we listen to, perform, and evaluate fine music; and, most important, (5) to help facilitate heightened moments of human awareness. In our experience participation in the live performance of fine music is potentially one of the highest social ends towards which we can aspire as performers, music students, and audience members. For it is in live, heightened moments of musical magic—when time stops and egos dissolve—that often we are made most conscious of our shared humanity. Armin Kelly, Founder and Artistic Director Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival Acknowledgements We wish to thank the following for their generous support of this event: The Cleveland Institute of Music: Gary Hanson, Interim President; Lori Wright, Director, Concerts and Events; Marjorie Gold, Concert Production Manager; Gina Rendall, Concert Facilities Coordinator; Susan Iler, Director of Marketing and Communications; Lynn M. -

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

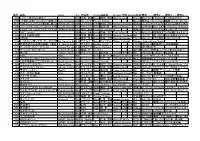

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst -

Measuring the Cultural Evolution of Music: with Case Studies of British-American and Japanese Folk, Art, and Popular Music

Measuring the cultural evolution of music: With case studies of British-American and Japanese folk, art, and popular music Patrick Evan SAVAGE This is an English version of my Japanese Ph.D. dissertation (Ph.D. conferred on March 27, 2017). The final Japanese version of record was deposited in the Japanese National Diet Library in June 2017. #2314910 Ph.D. entrance year: 2014 2016 academic year Tokyo University of the Arts, Department of Musicology Ph.D. dissertation Supervisor: UEMURA Yukio Supervisory committee: TSUKAHARA Yasuko MARUI Atsushi Hugh DE FERRANTI i English abstract Student number: 2314910 Name: Patrick Evan SAVAGE Title: Measuring the cultural evolution of music: With case studies of British-American and Japanese folk, art, and popular music Darwin's theory of evolution provided striking explanatory power that has come to unify biology and has been successfully extended to various social sciences. In this dissertation, I demonstrate how cultural evolutionary theory may also hold promise for explaining diverse musical phenomena, using a series of quantitative case studies from a variety of cultures and genres to demonstrate general laws governing musical change. Chapter one describes previous research and debates regarding music and cultural evolution. Drawing on major advances in the scientific understanding of cultural evolution over the past three decades, I clarify persistent misconceptions about the roles of genes and progress in definitions of evolution, showing that neither is required or assumed. I go on to review older and recent literature relevant to musical evolution at a variety of levels, from Lomax's macroevolutionary interpretation of global patterns of song-style to microevolutionary mechanisms by which minute melodic variations give rise to large tune families. -

166-90-06 Tel: +38(063)804-46-48 E-Mail: [email protected] Icq: 550-846-545 Skype: Doowopteenagedreams Viber: +38(063)804-46-48 Web

tel: +38(097)725-56-34 tel: +38(099)166-90-06 tel: +38(063)804-46-48 e-mail: [email protected] icq: 550-846-545 skype: doowopteenagedreams viber: +38(063)804-46-48 web: http://jdream.dp.ua CAT ORDER PRICE ITEM CNF ARTIST ALBUM LABEL REL G-049 $60,37 1 CD 19 Complete Best Ao&haru (jpn) CD 09/24/2008 G-049 $57,02 1 SHMCD 801 Latino: Limited (jmlp) (ltd) (shm) (jpn) CD 10/02/2015 G-049 $55,33 1 CD 1975 1975 (jpn) CD 01/28/2014 G-049 $153,23 1 SHMCD 100 Best Complete Tracks / Various (jpn)100 Best... Complete Tracks / Various (jpn) (shm) CD 07/08/2014 G-049 $48,93 1 CD 100 New Best Children's Classics 100 New Best Children's Classics AUDIO CD 07/15/2014 G-049 $40,85 1 SHMCD 10cc Deceptive Bends (shm) (jpn) CD 02/26/2013 G-049 $70,28 1 SHMCD 10cc Original Soundtrack (jpn) (ltd) (jmlp) (shm) CD 11/05/2013 G-049 $55,33 1 CD 10-feet Vandalize (jpn) CD 03/04/2008 G-049 $111,15 1 DVD 10th Anniversary-fantasia-in Tokyo Dome10th Anniversary-fantasia-in/... Tokyo Dome / (jpn) [US-Version,DVD Regio 1/A] 05/24/2011 G-049 $37,04 1 CD 12 Cellists Of The Berliner PhilharmonikerSouth American Getaway (jpn) CD 07/08/2014 G-049 $51,22 1 CD 14 Karat Soul Take Me Back (jpn) CD 08/21/2006 G-049 $66,17 1 CD 175r 7 (jpn) CD 02/22/2006 G-049 $68,61 2 CD/DVD 175r Bremen (bonus Dvd) (jpn) CD 04/25/2007 G-049 $66,17 1 CD 175r Bremen (jpn) CD 04/25/2007 G-049 $48,32 1 CD 175r Melody (jpn) CD 09/01/2004 G-049 $45,27 1 CD 175r Omae Ha Sugee (jpn) CD 04/15/2008 G-049 $66,92 1 CD 175r Thank You For The Music (jpn) CD 10/10/2007 G-049 $48,62 1 CD 1966 Quartet Help: Beatles Classics (jpn) CD 06/18/2013 G-049 $46,95 1 CD 20 Feet From Stardom / O. -

Francisco Tárrega (1852 – 1909

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO FACULDADE DE EDUCAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO CURSO DE DOUTORADO EM EDUCAÇÃO BRASILEIRA MARCO TULIO FERREIRA DA COSTA O VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ HABITUS E FORMAÇÃO MUSICAL Fortaleza – CE 2010 MARCO TULIO FERREIRA DA COSTA O VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ: HABITUS E FORMAÇÃO MUSICAL Tese de Doutorado submetida a defesa junto à Linha de Pesquisa: Educação, Currículo e Ensino / Eixo Temático Ensino de Música do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Brasileira da Universidade Federal do Ceará - UFC. Orientador: Professor Doutor Luiz Botelho Albuquerque Fortaleza – CE 2010 C874v Costa, Marco Túlio Ferreira da. O Violão Clube do Ceará: habitus e formação musical. / Marco Túlio Ferreira da Costa. – Fortaleza (CE), 2010. 131f. : il.; 31 cm. Tese (Doutorado) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Faculdade de Educação, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Fortaleza (CE), 2010. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Luiz Botelho Albuquerque. 1- VIOLÃO - ESTUDO E ENSINO. 2 – VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ - HISTÓRIA E CRÍTICA. 3- MÚSICA - ESTUDO E ENSINO – FORTALEZA (CE). 4- EDUCAÇÃO MUSICAL. 5- CULTURA E EDUCAÇÃO. 6 - ARTES - ESTUDO E ENSINO – FORTALEZA (CE). I - Albuquerque, Luiz Botelho (Orient). II - Universidade Federal do Ceará, Faculdade de Educação, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. III – Título. CDD: 787.87 07 MARCO TÚLIO FERREIRA DA COSTA O VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ HABITUS E FORMAÇÃO MUSICAL Área de Concentração: Ensino em Música APROVADO EM ____/_____/______ BANCA EXAMINADORA _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Luiz Botelho Albuquerque (UFC) Presidente da Banca _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Carlos Velásquez Rueda Examinador (UNIFOR) _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Elvis de Azevedo Mattos Examinador (UFC) _________________________________________________________ Profa Dra Ana Maria Iório Dias Examinadora (UFC) _________________________________________________________ Prof. -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally.