A Brief Sketch of San Diego's Military Presence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defense - Military Base Realignments and Closures (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 11, folder “Defense - Military Base Realignments and Closures (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 11 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON October 31, 197 5 MEMORANDUM TO: JACK MARSH FROM: RUSS ROURKE I discussed the Ft. Dix situation with Rep. Ed Forsythe again. As you may know, I reviewed the matter with Marty Hoffman at noon yesterday, and with Col. Kenneth Bailey several days ago. Actually, I exchanged intelligence information with him. Hoffman and Bailey advised me that no firm decision has as yet been made with regard to the retention of the training function at Dix. On Novem ber 5, Marty Hotfman will receive a briefing by Army staff on pos sible "back fill'' organizations that may be available to go to Dix in the event the training function moves out. -

Maurice “Bud” Carrigan U.S

1 Maurice “Bud” Carrigan U.S. Army 2nd Lieutenant –Transportation Corp largest convoy to ever leave the United States. There were 100 ships with 500 men on each. The purpose of the convoy was to prepare for the invasion of France on June 6, 1943. The troops were unloaded in North Africa not far from where one of the most memorable battles was about to take place “D-Day”. We lost one ship and that ship was carrying a local man from Springfield, IL. We proceeded empty to Naples, Italy and then returned to North Africa and picked up 500 German prison- ers to take back to the United States. One pris- oner developed appendicitis on the way to the States and needed an operation. All we had aboard were two Arab eye, ear, nose & throat specialists and a PFC (private first class) by the name of Patterson who had “some” medical training. Maurice “Bud” Carrigan U.S. Army 2nd Lieutenant –Transportation Corp I was drafted into the U. S. Army in September 1942 at 21 years of age. I received my basic training at Camp Callan in California near San Diego. I spent six months in California and was then sent to Camp Davis, North Carolina for officer training. I was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant in September 1943 as a anti-aircraft officer. For three months I was at a camp in Boston, Massachusetts and was then trans- ferred back to Camp Davis, North Carolina to learn Denver Plane Morris Code. About that time they decided they had too many officers in Anti-Aircraft and I was trans- ferred to the Transportation Corp. -

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION

CALIFORNIA HISTORIC MILITARY BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES INVENTORY VOLUME II: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIC RESOURCES OF THE MILITARY IN CALIFORNIA, 1769-1989 by Stephen D. Mikesell Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Prepared by: JRP JRP HISTORICAL CONSULTING SERVICES Davis, California 95616 March 2000 California llistoric Military Buildings and Stnictures Inventory, Volume II CONTENTS CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... i FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. iv PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1-1 2.0 COLONIAL ERA (1769-1846) .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Spanish-Mexican Era Buildings Owned by the Military ............................................... 2-8 2.2 Conclusions .................................................................................................................. -

Dissertation-Master Copy

Coloniality and Border(ed) Violence: San Diego, San Ysidro and the U-S///Mexico Border By Roberto Delgadillo Hernández A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Ramón Grosfoguel, Chair Professor José David Saldívar Professor Ignacio Chapela Professor Joseph Nevins Fall 2010 Coloniality and Border(ed) Violence: San Diego, San Ysidro and the U-S///Mexico Border © Copyright, 2010 By Roberto Delgadillo Hernández Abstract Coloniality and Border(ed) Violence: San Diego, San Ysidro and the U-S///Mexico Border By Roberto Delgadillo Hernández Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Ramón Grosfoguel, Chair Considered the “World's Busiest Border Crossing,” the San Ysidro port of entry is located in a small, predominantly Mexican and Spanish-speaking community between San Diego and Tijuana. The community of San Ysidro was itself annexed by the City of San Diego in the mid-1950s, in what was publicly articulated as a dispute over water rights. This dissertation argues that the annexation was over who was to have control of the port of entry, and would in turn, set the stage for a gendered/racialized power struggle that has contributed to both real and symbolic violence on the border. This dissertation is situated at the crossroads of urban studies, border studies and ethnic studies and places violence as a central analytical category. As such, this interdisciplinary work is manifold. It is a community history of San Ysidro in its simultaneous relationship to the U-S///Mexico border and to the City of San Diego. -

Summer 2019, Volume 65, Number 2

The Journal of The Journal of SanSan DiegoDiego HistoryHistory The Journal of San Diego History The San Diego History Center, founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928, has always been the catalyst for the preservation and promotion of the history of the San Diego region. The San Diego History Center makes history interesting and fun and seeks to engage audiences of all ages in connecting the past to the present and to set the stage for where our community is headed in the future. The organization operates museums in two National Historic Districts, the San Diego History Center and Research Archives in Balboa Park, and the Junípero Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The History Center is a lifelong learning center for all members of the community, providing outstanding educational programs for schoolchildren and popular programs for families and adults. The Research Archives serves residents, scholars, students, and researchers onsite and online. With its rich historical content, archived material, and online photo gallery, the San Diego History Center’s website is used by more than 1 million visitors annually. The San Diego History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate and one of the oldest and largest historical organizations on the West Coast. Front Cover: Illustration by contemporary artist Gene Locklear of Kumeyaay observing the settlement on Presidio Hill, c. 1770. Back Cover: View of Presidio Hill looking southwest, c. 1874 (SDHC #11675-2). Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Copy Edits: Samantha Alberts Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

The Pacific Guano Islands: the Stirring of American Empire in the Pacific Ocean

THE PACIFIC GUANO ISLANDS: THE STIRRING OF AMERICAN EMPIRE IN THE PACIFIC OCEAN Dan O’Donnell Stafford Heights, Queensland, Australia The Pacific guano trade, a “curious episode” among United States over- seas ventures in the nineteenth century,1 saw exclusive American rights proclaimed over three scores of scattered Pacific islands, with the claims legitimized by a formal act of Congress. The United States Guano Act of 18 August 1856 guaranteed to enterprising American guano traders the full weight and authority of the United States government, while every other power was denied access to the deposits of rich fertilizer.2 While the act specifically declared that the United States was not obliged to “retain possession of the islands” once they were stripped of guano, some with strategic and commercial potential apart from the riches of centuries of bird droppings have been retained to this day. Of critical importance in the Guano Act, from the viewpoint of exclusive or sovereign rights, was the clause empowering the president to “employ the land and naval forces of the United States” to protect American rights. Another clause declared that the “introduction of guano from such islands, rocks or keys shall be regulated as in the coastal trade between different parts of the United States, and the same laws shall govern the vessels concerned therein.” The real significance of this clause lay in the monopoly afforded American vessels in the carry- ing trade. “Foreign vessels must, of course, be excluded and the privi- lege confined to the duly documented vessels of the United States,” the act stated. -

The Western Services of Stephen Watts Kearny, 1815•Fi1848

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 21 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-1946 The Western Services of Stephen Watts Kearny, 1815–1848 Mendell Lee Taylor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Taylor, Mendell Lee. "The Western Services of Stephen Watts Kearny, 1815–1848." New Mexico Historical Review 21, 3 (1946). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol21/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. ________STEPHEN_WATTS KEARNY NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW VOL. XXI JULY, 1946 NO.3 THE WESTERN SERVICES OF STEPHEN WATTS KEARNY, 1815-18.48 By *MENDELL LEE TAYLOR TEPHEN WATTS KEARNY, the fifteenth child of Phillip and S. Susannah Kearny, was born at Newark, New Jersey, August 30, 1794. He lived in New Jersey until he matricu lated in Columbia University in 1809. While here the na tional crisis of 1812 brought his natural aptitudes to the forefront. When a call· for volunteers was made for the War of 1812, Kearny enlisted, even though he was only a few weeks away from a Bachelor of Arts degree. In the early part of the war he was captured at the battle of Queenstown. But an exchange of prisoners soon brought him to Boston. Later, for gallantry at Queenstown, he received a captaincy on April 1, 1813. After the Treaty of Ghent the army staff was cut' as much as possible. -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

U.S.S. San Diego

U.S.S. San Diego - Crescent Boat Company newspaper advertisement for 25 cent round trip ride to visit “The Pride of the Pacific Fleet, U.S.S. San Diego.” Features photograph of the ship. Possible date near September 14, 1914. Cut and pasted; no date or named newspaper. - September14,1914 news clipping from the San Diego Union entitled “San Diego Reaches Home Port For Unveiling of Magic Name; Mayor’s Daughter Will Be Sponsor at Rechristening.” Photos of stern of the big warship showing the new nameplate “San Diego”, Capt. Ashley H. Robertson, members of crew with ship’s mascot, “Sailor”, and view of Cruiser “San Diego” entering her home port. - April 15, 1914 newspaper clipping fro the San Diego Union advertising that the U.S. Cruiser San Diego is open to visitors everyday, launching from the Star Boat House Foot of Market Street. Photo of cruiser featured. - September 17, 1914 The San Diego Union front page “San Diego Favored As Advance War Base. Allies Surround Germans Under General Von Kluck at Amiens. Thousand Flags Wave O’er Harbor Honoring Pride of Pacific Fleet.” Photo of USS San Diego with flags and a hydroplane flying over. Cruiser was christened the preceding day by Miss Annie May O’Neall, the daughter of Mayor and Mrs. Charles F. O’Neall, “a typical daughter of the southland.” Photos of Miss Annie May and Rufus Choate, President of the Chamber of Commerce. - August 31, 1945 Los Angeles Examiner news page full of photos: “Thrill of Freedom. Allies in Japan Liberated. Yanks Take Over. Yokosuka. -

Djibouti: Z Z Z Z Summary Points Z Z Z Z Renewal Ofdomesticpoliticallegitimacy

briefing paper page 1 Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub David Styan Africa Programme | April 2013 | AFP BP 2013/01 Summary points zz Change in Djibouti’s economic and strategic options has been driven by four factors: the Ethiopian–Eritrean war of 1998–2000, the impact of Ethiopia’s economic transformation and growth upon trade; shifts in US strategy since 9/11, and the upsurge in piracy along the Gulf of Aden and Somali coasts. zz With the expansion of the US AFRICOM base, the reconfiguration of France’s military presence and the establishment of Japanese and other military facilities, Djibouti has become an international maritime and military laboratory where new forms of cooperation are being developed. zz Djibouti has accelerated plans for regional economic integration. Building on close ties with Ethiopia, existing port upgrades and electricity grid integration will be enhanced by the development of the northern port of Tadjourah. zz These strategic and economic shifts have yet to be matched by internal political reforms, and growth needs to be linked to strategies for job creation and a renewal of domestic political legitimacy. www.chathamhouse.org Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub page 2 Djibouti 0 25 50 km 0 10 20 30 mi Red Sea National capital District capital Ras Doumeira Town, village B Airport, airstrip a b Wadis ERITREA a l- M International boundary a n d District boundary a b Main road Railway Moussa Ali ETHIOPIA OBOCK N11 N11 To Elidar Balho Obock N14 TADJOURA N11 N14 Gulf of Aden Tadjoura N9 Galafi Lac Assal Golfe de Tadjoura N1 N9 N9 Doraleh DJIBOUTI N1 Ghoubbet Arta N9 El Kharab DJIBOUTI N9 N1 DIKHIL N5 N1 N1 ALI SABIEH N5 N5 Abhe Bad N1 (Lac Abhe) Ali Sabieh DJIBOUTI Dikhil N5 To Dire Dawa SOMALIA/ ETHIOPIA SOMALILAND Source: United Nations Department of Field Support, Cartographic Section, Djibouti Map No. -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph. -

Flight–Provide Access to Wind-Powered

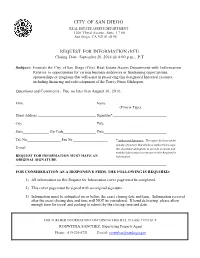

CITY OF SAN DIEGO REAL ESTATE ASSETS DEPARTMENT 1200 Third Avenue, Suite 1700 San Diego, CA 92101-4195 REQUEST FOR INFORMATION (RFI) Closing Date: September 20, 2016 @ 4:00 p.m., P.T. Subject: Furnish the City of San Diego (City) Real Estate Assets Department with Information Relative to opportunities for various business endeavors or fundraising opportunities, sponsorships or programs that will assist in preserving this designated historical resource including financing and redevelopment of the Torrey Pines Gliderport. Questions and Comments: Due no later than August 30, 2016. Firm Name (Print or Type) Street Address Signature* City Title State Zip Code Date Tel. No. Fax No. *Authorized Signature: The signer declares under penalty of perjury that she/he is authorized to sign E-mail this document and agrees to provide accurate and truthful information in response to this Request for REQUEST FOR INFORMATION MUST HAVE AN Information ORIGINAL SIGNATURE FOR CONSIDERATION AS A RESPONSIVE FIRM, THE FOLLOWING IS REQUIRED: 1) All information on this Request for Information cover page must be completed. 2) This cover page must be signed with an original signature. 3) Information must be submitted on or before the exact closing date and time. Information received after the exact closing date and time will NOT be considered. If hand delivering, please allow enough time for travel and parking to submit by the closing time and date. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONCERNING THIS RFI, PLEASE CONTACT: ROSWITHA SANCHEZ, Supervising Property Agent Phone: 619-236-6721 E-mail: [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION A. BACKGROUND The City-owned Torrey Pines Gliderport (Gliderport) is located at 2800 Torrey Pines Scenic Drive, situated within the City’s Torey Pines City Park.