Three Tales by Steve Reich and Beryl Korot – Sounds, Samples and Representations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Your Classroom Go

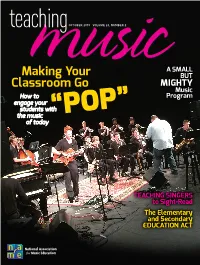

teaching OCTOBER 2015 VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 A SMALL Makingmusicmusic Your BUT Classroom Go MIGHTY Music How to Program engage your students with the music “POP” of today TEACHING SINGERS to Sight-Read The Elementary and Secondary EDUCATION ACT QuaverFindOutAd_NAfME_Aug15.pdf 1 7/30/15 12:26 PM Find out what these districts already know... Quaver is revolutionizing music education! TM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Packed with nearly 1,000 Songs! Try 36 Lessons from our K-8 Curriculum! Just go to QuaverMusic.com/Preview and begin your FREE 30-day trial today! ©2015 QuaverMusic.com, LLC October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 contentsMUSIC EDUCATION ● ORCHESTRATING SUCCESS Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 28 Teachers and students alike can rock out and learn with pop music! FEATURES 24 TEACHING SINGERS 28 POP AND ROCK GOES 32 EL SISTEMA TODAY 38 SMALL SCHOOL, TO READ THE PROGRAM! José Antonio Abreu’s BIG EFFORT, Instructing students in Pop music connects creation has taken GREAT SUCCESS the art and techniques instantly with many root in the U.S. and Alexandria Hanessian’s of sight-singing can reap students. How can continues to grow small but mighty middle many rewards in your music educators use through programs such school program thrives choral rehearsals and it in their classrooms as the Corona Youth in Spencertown, beyond. to increase student Music Project and New York. engagement? Juneau Alaska Music Matters. Photo by Little Kids Rock. Photo by nafme.org 1 October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 Student composers contents (far left and right) work with teachers Conductor Marin Alsop 56 at Williamsville East works with students in High School. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

ZGMTH - the Order of Things

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bangor University Research Portal The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve ANGOR UNIVERSITY Reich Bakker, Twila; ap Sion, Pwyll Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie DOI: 10.31751/1003 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/06/2019 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Bakker, T., & ap Sion, P. (2019). The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve Reich. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie, 16(1), 99-122. https://doi.org/10.31751/1003 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 ZGMTH - The Order of Things https://www.gmth.de/zeitschrift/artikel/1003.aspx Inhalt (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/inhalt.aspx) Impressum (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/impressum.aspx) Autorinnen und Autoren (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/autoren.aspx) Home (/home.aspx) Bakker, Twila / ap Siôn, Pwyll (2019): The Order of Things. -

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First I

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First International Conference on Music and Minimalism University of Wales, Bangor Friday, August 31, 2007 Minimalism is perhaps one of the most misunderstood musical movements of the latter half of the twentieth century. Even among musicians, there is considerable disagreement as to the meaning of the term “minimalism” and which pieces should be categorized under this broad heading.1 Furthermore, minimalism is often referenced using negative terminology such as “trance music” or “stuck-needle music.” Yet, its impact cannot be overstated, influencing both composers of art and rock music. Within the original group of minimalists, consisting of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass2, the latter two have received considerable attention and many of their works are widely known, even to non-musicians. However, Terry Riley is one of the most innovative members of this auspicious group, and yet, he has not always received the appropriate recognition that he deserves. Most musicians familiar with twentieth century music realize that he is the composer of In C, a work widely considered to be the piece that actually launched the minimalist movement. But is it really his first minimalist work? Two pieces that Riley wrote early in his career as a graduate student at Berkeley warrant closer attention. Riley composed his String Quartet in 1960 and the String Trio the following year. These two works are virtually unknown today, but they exhibit some interesting minimalist tendencies and indeed foreshadow some of Riley’s later developments. -

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll Ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) *

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) * Orit Hilewicz NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hilewicz.php KEYWORDS: Steve Reich, analysis, politics DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.1.0 Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory [1] This past September, a scandal erupted on social media when a 2018 book excerpt was posted that showed a few lines from an interview with British photographer and music writer Val Wilmer. Wilmer recounted her meeting with Steve Reich in the early 1970s: I was talking about a person who was playing with him—who happened to be an African-American who was a friend of mine. I can tell you this now because I feel I must . we were talking and I mentioned this man, and [Reich] said, “Oh yes, well of course, he’s one of the only Blacks you can talk to.” So I said, “Oh really?” He said, “Blacks are geing ridiculous in the States now.” And I thought, “This is a man who’s just done this piece called Drumming which everybody cites as a great thing. He’s gone and ripped off stuff he’s heard in Ghana—and he’s telling me that Blacks are ridiculous in the States now.” I rest my case. Wouldn’t you be politicized? (Wilmer 2018, 60) Following recent revelations of racist and misogynist statements by central musical figures and calls for music scholarship to come to terms with its underlying patriarchal and white racial frame, (1) the new edited volume on Reich suggests directions music scholarship could take in order to examine the political, economic, and cultural environments in which musical works are composed, performed, and received. -

Thirty Talented Young Flutists Participated in The

The New York Flute Club N E W S L E T T E R April 2002 2002 Young Artist Competition Winners hirty talented young flutists participated in the New York Flute Club’s annual competition. The judges T were Bart Feller, Tara Helen O’Connor, and Susan In Concert Palma; Patricia Zuber was the competition coordinator. 2002 NYFC Young Artist Competition Winners FIRST PRIZE YONG MA was born in Huainan, China. From 1987 to 1996 he was principal flutist of the China Sunday, April 28, 2002, 5:30 pm Youth Orchestra and of the China Youth CAMI Hall Symphony while he studied at the Central 165 West 57th Street, NYC Conservatory of Music in Beijing. His flute teacher there was Yongxin Wang. At the age Program of thirteen he was one of the finalists in the “Prague Spring” International Music Competi- Suh-Young Park, flute; Linda Mark, piano tion in Czechoslovakia. In 1999 Mr. Ma was Fantasie on themes Paul Taffanel from “Der Freischutz” the winner of the Olga Koussevitzky Wood- by C.M. von Weber wind Competition in New York. The follow- ing year he won first prize in the Young Soo Yun Kim, flute; Linda Mark, piano Artist Competition of the Flute Society of Sonata in E Minor Georg Philipp Telemann Washington. Mr. Ma is currently in his third Chant de Linos André Jolivet year at the Juilliard School, where he is a student of Carol Wincenc. ❑ Yong Ma, flute; Linda Mark, piano Cantabile and Presto Georges Enesco 1. Cantabile SECOND PRIZE SOO YUN KIM was born in Seoul, Korea, where she attended the Seoul Arts High School. -

The Desert Music' at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Next Wave Festival

Swarthmore College Works English Literature Faculty Works English Literature 1984 Steve Reich's 'The Desert Music' At The Brooklyn Academy Of Music's Next Wave Festival Peter Schmidt Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-english-lit Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Peter Schmidt. (1984). "Steve Reich's 'The Desert Music' At The Brooklyn Academy Of Music's Next Wave Festival". William Carlos Williams Review. Volume 10, Issue 2. 25-25. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-english-lit/211 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Literature Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 25 Steve Reich's The Desert Music at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Next Wave Festival "For music is changing in character today as it has always done." -WCW (SE 57) On October 25-27, the 1984 Next Wave Festival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music presented the American premiere of Steve Reich's The Desert Music, a piece for chorus and orchestra setting to music excerpts from three poems by William Carlos Williams, "Asphodel, That Greeny Flower," "The Orchestra," and his translation of Theocritus' Idyl I. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted the Brooklyn Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra and chorus, and he, the musicians, and the composer received standing ovations after the performances. Steve Reich is one of this country's most promising young composers. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Singing corporeality: reinventing the vocalic body in postopera Novak, J. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Novak, J. (2012). Singing corporeality: reinventing the vocalic body in postopera. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 Chapter 3 Monstrous Singing: The Politics of Vocal Existence169 “Today monsters remind us of the exclusion of the human from life, of life that is more and more being divided from humanity (...)”170 Bojana Kunst „Every creature has a song – the song of the dogs – and the song of the doves – the song of the fly – the song of the fox.- What do they say?“171 Adin Steinsaltz In this chapter my concern is with how singing appears monstrous as a result of existing beyond the body that produces it, with the politics of the monstrous voice and with the consequences this has for the opera. -

Steve Reich and Hebrew Cantillation Author(S): Antonella Puca Source: the Musical Quarterly, Vol

Steve Reich and Hebrew Cantillation Author(s): Antonella Puca Source: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 81, No. 4 (Winter, 1997), pp. 537-555 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/742285 Accessed: 03-10-2018 20:46 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Quarterly This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Wed, 03 Oct 2018 20:46:38 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Twentieth Century Steve Reich and Hebrew Cantillation Antonella Puca Among the composers of the American avant-garde, Steve Reich is one of the most strongly aware of his cultural and ethnic roots. His interest in Hebrew cantillation dates from the mid-1970s and is accompanied by the rediscovery of his own Jewish background, by the study of the Hebrew language and of the Hebrew Bible, and by extended periods of residence in Israel. My paper considers the influence of Hebrew cantillation on Reich's compositional techniques and on his approach to the relation between words and music in his works from the 1980s and early 1990s. -

Britten in Beijing

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited February 2013 2013/1 Reich Radio Rewrite Britten in Beijing Steve Reich’s new ensemble work, with first performances in Included in this issue: The Britten centenary sees the composer’s drawings, resulting in a spectacular series of the UK and US in March, draws inspiration from songs by music celebrated worldwide including many animal lanterns handcrafted in Shangdong van der Aa Radiohead. works receiving territorial premieres, from Province. The production used the biblical Interview about his new 3D song through to reworkings by Stravinsky. South America to Asia and the Antipodes. tale of Noah to explore contemporary film opera Sunken Garden “It was not my intention to make anything like As an upbeat to this year’s events, the first ecological concerns. Through a series of ‘variations’ on these songs, but rather to Britten opera was staged in China with a educational projects, Noye’s Fludde provided draw on their harmonies and sometimes Noye’s Fludde collaboration between an illustration of man’s struggle with the melodic fragments and work them into my Northern Ireland Opera, the KT Wong environment and the significance of flood own piece. As to actually hearing the original Foundation and the Beijing Music Festival. mythology to both Chinese and Western cultures. songs, the truth is – sometimes you hear First staged in Belfast Zoo last summer as them and sometimes you don’t.” part of the Cultural Olympiad, Oliver Mears’s Overseas Britten highlights in 2013 include Photo: Wonge Bergmann Reich encountered the music of Radiohead production transferred in October to Beijing as territorial opera premieres in Brazil, Chile, following a performance by Jonny part of the UK Now Festival. -

HENRY and LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL of MUSIC SPRING 2017 Fanfare

HENRY AND LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC SPRING 2017 fanfare 124488.indd 1 4/19/17 5:39 PM first chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN One sign of a school’s stature is the recognition received by its students and faculty. By that measure, in recent months the eminence of the Bienen School of Music has been repeatedly reaffirmed. For the first time in the history of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, this spring one of the contestants will be a Northwestern student. EunAe Lee, a doctoral student of James Giles, is one of only 30 pianists chosen from among 290 applicants worldwide for the prestigious competition. The 15th Van Cliburn takes place in May in Ft. Worth, Texas. Also in May, two cello students of Hans Jørgen Jensen will compete in the inaugural Queen Elisabeth Cello Competition in Brussels. Senior Brannon Cho and master’s student Sihao He are among the 70 elite cellists chosen to participate. Xuesha Hu, a master’s piano student of Alan Chow, won first prize in the eighth Bösendorfer and Yamaha USASU Inter national Piano Competition. In addition to receiving a $15,000 cash prize, Hu will perform with the Phoenix Symphony and will be presented in recital in New York City’s Merkin Concert Hall. Jason Rosenholtz-Witt, a doctoral candidate in musicology, was awarded a 2017 Northwestern Presidential Fellowship. Administered by the Graduate School, it is the University’s most prestigious fellowship for graduate students. Daniel Dehaan, a music composition doctoral student, has been named a 2016–17 Field Fellow by the University of Chicago.