Haiti's First-Ever Private Nature Reserve the Rediscovery of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution of Bufotes Latastii (Boulenger, 1882), Endemic to the Western Himalaya

Alytes, 2018, 36 (1–4): 314–327. Distribution of Bufotes latastii (Boulenger, 1882), endemic to the Western Himalaya 1* 1 2,3 4 Spartak N. LITVINCHUK , Dmitriy V. SKORINOV , Glib O. MAZEPA & LeO J. BORKIN 1Institute Of Cytology, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Tikhoretsky pr. 4, St. Petersburg 194064, Russia. 2Department of Ecology and EvolutiOn, University of LauSanne, BiOphOre Building, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland. 3 Department Of EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy, EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy Centre (EBC), Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. 4ZoOlOgical Institute, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, St. PeterSburg 199034, Russia. * CorreSpOnding author <[email protected]>. The distribution of Bufotes latastii, a diploid green toad species, is analyzed based on field observations and literature data. 74 localities are known, although 7 ones should be confirmed. The range of B. latastii is confined to northern Pakistan, Kashmir Valley and western Ladakh in India. All records of “green toads” (“Bufo viridis”) beyond this region belong to other species, both to green toads of the genus Bufotes or to toads of the genus Duttaphrynus. B. latastii is endemic to the Western Himalaya. Its allopatric range lies between those of bisexual triploid green toads in the west and in the east. B. latastii was found at altitudes from 780 to 3200 m above sea level. Environmental niche modelling was applied to predict the potential distribution range of the species. Altitude was the variable with the highest percent contribution for the explanation of the species distribution (36 %). urn:lSid:zOobank.Org:pub:0C76EE11-5D11-4FAB-9FA9-918959833BA5 INTRODUCTION Bufotes latastii (fig. 1) iS a relatively cOmmOn green toad species which spreads in KaShmir Valley, Ladakh and adjacent regiOnS Of nOrthern India and PakiStan. -

Phalangeal Bone Anomalies in the European Common Toad Bufo Bufo from Polluted Environments

Environ Sci Pollut Res DOI 10.1007/s11356-016-7297-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Phalangeal bone anomalies in the European common toad Bufo bufo from polluted environments Mikołaj Kaczmarski1 & Krzysztof Kolenda 2 & Beata Rozenblut-Kościsty2 & Wioletta Sośnicka 2 Received: 7 March 2016 /Accepted: 20 July 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Every spring, many of amphibians are killed by ximately 20 % from the rural and semi-urban sites. In partic- motor vehicles on roads. These road-killed animals can be ular, we found hypertrophic bone cells, misaligned intercellu- used as valuable material for non-invasive studies showing lar substance, and irregular outer edges of bones. We suggest the effect of environmental pollution on amphibian popula- that these malformations are caused by different pollution, e.g. tions. The aims of our research were to check whether the with heavy metals. phalanges of road-killed toads may be useful as material for histological analysis, and whether various degrees of human Keywords Amphibians . Phalangeal bone . Poland . impact influence the level in bone abnormalities in the com- Pollution . Roadkilling . Skeletochronology . Urban area mon toad. We also examined whether the sex and age struc- ture of toads can differ significantly depending in the different sites. We chose three toad breeding sites where road-killed Introduction individuals had been observed: near the centre of a city, the outskirts of a city, and a rural site. We collected dead individ- Current knowledge widely indicates a direct relationship be- uals during spring migration in 2013. The sex of each individ- tween anthropogenic pressures and the deteriorating environ- ual was determined and the toes were used to determine age mental state and/or global extinction of amphibian popula- using the skeletochronology method. -

Toads Have Warts... and That's Good! | Nature Detectives | Summer 2021

Summer 2021 TOADS HAVE WARTS…AND THAT’S GOOD! Warts on your skin are not good. Warts can occur when a virus sneaks into human skin through a cut. A medicine gets rid of the virus and then it’s good-bye ugly wart. Toad warts look slightly like human warts, but toad warts and people warts are not one bit the same. Toad warts are natural bumps on a toad’s back. Toads have larger lumps behind their eyes. The bumps and lumps are glands. The glands produce a whitish goo that is a foul-tasting and smelly poison. The poison is a toad’s ultimate defense in a predator attack. It is toxic enough to kill small animals, if they swallow enough of it. The toxin can cause skin and eye irritation in humans. Some people used to think toad warts were contagious. Touching a toad can’t cause human warts, but licking a toad might make you sick! Toads have other defenses too. Their camouflage green/gray/brown colors blend perfectly into their surroundings. They can puff up with air to look bigger, and maybe less appetizing. Pull Out and Save Pull Out and Pick one up, and it might pee on your hand. Toads Travel, Frogs Swim Toads and frogs are amphibians with some similarities and quite a few differences. Amphibians spend all or part of their life in water. Frogs have moist, smooth skin that loses moisture easily. A toad’s dry, bumpy skin doesn’t lose water as easily as frog skin. Frogs are always in water or very near it, otherwise they quickly dehydrate and die. -

Abstract Book

Welcome to the Ornithological Congress of the Americas! Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina, from 8–11 August, 2017 Puerto Iguazú is located in the heart of the interior Atlantic Forest and is the portal to the Iguazú Falls, one of the world’s Seven Natural Wonders and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The area surrounding Puerto Iguazú, the province of Misiones and neighboring regions of Paraguay and Brazil offers many scenic attractions and natural areas such as Iguazú National Park, and provides unique opportunities for birdwatching. Over 500 species have been recorded, including many Atlantic Forest endemics like the Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia caudata), the emblem of our congress. This is the first meeting collaboratively organized by the Association of Field Ornithologists, Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia and Aves Argentinas, and promises to be an outstanding professional experience for both students and researchers. The congress will feature workshops, symposia, over 400 scientific presentations, 7 internationally renowned plenary speakers, and a celebration of 100 years of Aves Argentinas! Enjoy the book of abstracts! ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIR: Valentina Ferretti, Instituto de Ecología, Genética y Evolución de Buenos Aires (IEGEBA- CONICET) and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Andrés Bosso, Administración de Parques Nacionales (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable) Reed Bowman, Archbold Biological Station and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Gustavo Sebastián Cabanne, División Ornitología, Museo Argentino -

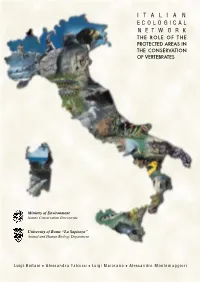

I T a L I a N Ecological N E T W O

I T A L I A N E C O L O G I C A L N E T W O R K THE ROLE OF THE PROTECTED AREAS IN THE CONSERVATION OF VERTEBRATES Ministry of Environment Nature Conservation Directorate University of Rome “La Sapienza” Animal and Human Biology Department In collaboration with: IE A Institute o f A p p lie d Ecolo g y Via L. Spallanzani, 32 - 00161 Rome - Italy Tel./fax: +39 06 4403315 - e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 88- 87736- 03- 0 Luigi B oit a ni ● A less a n d r a F a lcucci ● Luigi M a io r a n o ● A less a n d ro M o nte m a g gio ri I T A L I A N E C O L O G I C A L N E T W O R K THE ROLE OF THE PROTECTED AREAS IN THE CONSERVATION OF VERTEBRATES Luigi Boitani Animal and Human Biology Department, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Alessandra Falcucci College of N atural Resources, Department of Fish and W ildlife Resources University of Idaho, Moscow (USA) Animal and Human Biology Department, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Luigi Maiorano College of N atural Resources, Department of Fish and W ildlife Resources University of Idaho, Moscow (USA) Animal and Human Biology Department, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Alessandro Montemaggiori Animal and Human Biology Department, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Institute of Applied Ecology, Rome September 2003 Recommended citation: Boitani L., A. Falcucci, L. Maiorano & A. Montemaggiori. -

Veterans Park Herpetological Report Manning 2015

To Whom It May Concern, The information in this document is the summary of a series of volunteer reptile and amphibian observations conducted in Hamilton Veteran’s Park in Mercer County, NJ. The document has been prepared for the Township of Hamilton. The results presented are from field observations and data collected in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. The data from the first three years was taken informally during morning and evening walks with family. The data from 2015 was taken for a volunteer reptile and amphibian survey performed upon the request of the Township of Hamilton, Mercer County, NJ. This information is presented voluntarily for use in conservation endeavors. General Profile: Hamilton Veteran’s Park is a 350‐acre park managed by the Township of Hamilton in Mercer County, New Jersey. The park features a diversity of habitats within its boundaries, including a field which was the site of a former farm, a wetlands meadow, a smaller upland meadow, several patches of deciduous forest, a man‐made lake, temporary and permanent wetlands, an intermittent stream, and several permanent streams. The park is located on the physiographic province known as the inner coastal plain. Comments on General Fauna: The Veteran’s Park property provides a variety of habitats for native fauna to flourish. Healthy numbers of invertebrates have been observed during the survey. Checking under logs and other cover debris reveals a multitude of native decomposers, such as ants, earthworms, slugs, centipedes, harvestmen, and others. Ticks are occasionally seen in the fields, however most of those observed were dog ticks. -

DNR Letterhead

ATU F N RA O L T R N E E S M O T U STATE OF MICHIGAN R R C A P DNR E E S D MI N DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES CHIG A JENNIFER M. GRANHOLM LANSING REBECCA A. HUMPHRIES GOVERNOR DIRECTOR Michigan Frog and Toad Survey 2009 Data Summary There were 759 unique sites surveyed in Zone 1, 218 in Zone 2, 20 in Zone 3, and 100 in Zone 4, for a total of 1097 sites statewide. This is a slight decrease from the number of sites statewide surveyed last year. Zone 3 (the eastern half of the Upper Peninsula) is significantly declining in routes. Recruiting in that area has become necessary. A few of the species (i.e. Fowler’s toad, Blanchard’s cricket frog, and mink frog) have ranges that include only a portion of the state. As was done in previous years, only data from those sites within the native range of those species were used in analyses. A calling index of abundance of 0, 1, 2, or 3 (less abundant to more abundant) is assigned for each species at each site. Calling indices were averaged for a particular species for each zone (Tables 1-4). This will vary widely and cannot be considered a good estimate of abundance. Calling varies greatly with weather conditions. Calling indices will also vary between observers. Results from the evaluation of methods and data quality showed that volunteers were very reliable in their abilities to identify species by their calls, but there was variability in abundance estimation (Genet and Sargent 2003). -

Mitochondrial Discordance and Gene Flow in a Recent Radiation of Toads

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 59 (2011) 66–80 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Nuclear–mitochondrial discordance and gene flow in a recent radiation of toads ⇑ Brian E. Fontenot , Robert Makowsky 1, Paul T. Chippindale Department of Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76019, United States article info abstract Article history: Natural hybridization among recently diverged species has traditionally been viewed as a homogenizing Received 28 April 2010 force, but recent research has revealed a possible role for interspecific gene flow in facilitating species Revised 12 December 2010 radiations. Natural hybridization can actually contribute to radiations by introducing novel genes or Accepted 23 December 2010 reshuffling existing genetic variation among diverging species. Species that have been affected by natural Available online 19 January 2011 hybridization often demonstrate patterns of discordance between phylogenies generated using nuclear and mitochondrial markers. We used Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) data in conjunc- Keywords: tion with mitochondrial DNA in order to examine patterns of gene flow and nuclear–mitochondrial dis- Toads cordance in the Anaxyrus americanus group, a recent radiation of North American toads. We found high Hybridization Gene flow levels of gene flow between putative species, particularly in species pairs sharing similar male advertise- Speciation ment calls that occur in close geographic proximity, suggesting that prezygotic reproductive isolating AFLPs mechanisms and isolation by distance are the primary determinants of gene flow and genetic differenti- Nuclear–mitochondrial discordance ation among these species. Additionally, phylogenies generated using AFLP and mitochondrial data were markedly discordant, likely due to recent and/or ongoing natural hybridization events between sympatric populations. -

Maritime Southeast Asia and Oceania Regional Focus

November 2011 Vol. 99 www.amphibians.orgFrogLogNews from the herpetological community Regional Focus Maritime Southeast Asia and Oceania INSIDE News from the ASG Regional Updates Global Focus Recent Publications General Announcements And More..... Spotted Treefrog Nyctixalus pictus. Photo: Leong Tzi Ming New The 2012 Sabin Members’ Award for Amphibian Conservation is now Bulletin open for nomination Board FrogLog Vol. 99 | November 2011 | 1 Follow the ASG on facebook www.facebook.com/amphibiansdotor2 | FrogLog Vol. 99| November 2011 g $PSKLELDQ$UN FDOHQGDUVDUHQRZDYDLODEOH 7KHWZHOYHVSHFWDFXODUZLQQLQJSKRWRVIURP $PSKLELDQ$UN¶VLQWHUQDWLRQDODPSKLELDQ SKRWRJUDSK\FRPSHWLWLRQKDYHEHHQLQFOXGHGLQ $PSKLELDQ$UN¶VEHDXWLIXOZDOOFDOHQGDU7KH FDOHQGDUVDUHQRZDYDLODEOHIRUVDOHDQGSURFHHGV DPSKLELDQDUN IURPVDOHVZLOOJRWRZDUGVVDYLQJWKUHDWHQHG :DOOFDOHQGDU DPSKLELDQVSHFLHV 3ULFLQJIRUFDOHQGDUVYDULHVGHSHQGLQJRQ WKHQXPEHURIFDOHQGDUVRUGHUHG±WKHPRUH \RXRUGHUWKHPRUH\RXVDYH2UGHUVRI FDOHQGDUVDUHSULFHGDW86HDFKRUGHUV RIEHWZHHQFDOHQGDUVGURSWKHSULFHWR 86HDFKDQGRUGHUVRIDUHSULFHGDW MXVW86HDFK 7KHVHSULFHVGRQRWLQFOXGH VKLSSLQJ $VZHOODVRUGHULQJFDOHQGDUVIRU\RXUVHOIIULHQGV DQGIDPLO\ZK\QRWSXUFKDVHVRPHFDOHQGDUV IRUUHVDOHWKURXJK\RXU UHWDLORXWOHWVRUIRUJLIWV IRUVWDIIVSRQVRUVRUIRU IXQGUDLVLQJHYHQWV" 2UGHU\RXUFDOHQGDUVIURPRXUZHEVLWH ZZZDPSKLELDQDUNRUJFDOHQGDURUGHUIRUP 5HPHPEHU±DVZHOODVKDYLQJDVSHFWDFXODUFDOHQGDU WRNHHSWUDFNRIDOO\RXULPSRUWDQWGDWHV\RX¶OODOVREH GLUHFWO\KHOSLQJWRVDYHDPSKLELDQVDVDOOSUR¿WVZLOOEH XVHGWRVXSSRUWDPSKLELDQFRQVHUYDWLRQSURMHFWV ZZZDPSKLELDQDUNRUJ FrogLog Vol. 99 | November -

Herpetofauna of the Podkielecki Landscape Protection Area

Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Vol. 30 No 2(80): 32-40 Ochrona Środowiska i Zasobów Naturalnych DOI 10.2478/oszn-2019-0008 Dariusz Wojdan*, Ilona Żeber-Dzikowska**, Barbara Gworek***, Agnieszka Pastuszko****, Jarosław Chmielewski***** Herpetofauna of the Podkielecki Landscape Protection Area * Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach, ** Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa w Płocku, *** Szkoła Główna Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego w Warszawie, **** Instytut Ochrony Środowiska - Państwowy Instytut Badawczy w Warszawie, ***** Wyższa Szkoła Rehabilitacji w Warszawie; e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Amphibians, reptiles, occurrence, biology, phenology, Podkielecki Landscape Protection Area Abstract The study was conducted in 2016-2017 in the Podkielecki Landscape Protection Area (area 26,485 ha). It was focused on the occurrence and distribution of amphibians and reptiles, the biology of the selected species and the existing threats. Established in 1995, the Podkielecki Landscape Protection Area surrounds the city of Kielce from the north, east and south-east, and adjoins several other protected areas. It covers the western part of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains (part of the Klonowskie and Masłowskie ranges) and the southern part of the Suchedniów Plateau. The studied area is mostly covered by forest and thicket communities (48.1%) and farmlands (39.9%), followed by built-up areas (7.8%), industrial areas (0.5%), roads and railways (2.7%), and surface water bodies (1%). The protected area is developed mainly on Palaeozoic rocks, including Cambrian and Ordovician sandstones, Silurian and Carboniferous shales, and Devonian marls. Podzolic soils predominate among soils. The largest rivers include Lubrzanka, Czarna Nida, Bobrza and Belnianka. There are no natural lakes within the PLPA limits, and the largest artificial reservoirs include the Cedzyna Reservoir, Morawica Reservoir, Suków Sandpit and two sedimentation reservoirs of the Kielce Power Plant. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Bollettino Del Museo Di Storia Naturale Di Venezia 67

Bollettino del Museo di Storia Naturale di Venezia, 67: 71-75 71 Nicola Novarini, Emanuele Stival WADING BIRDS PREDATION ON BUFOTES VIRIDIS (LAURENTI, 1768) IN THE CA’ VALLESINA WETLAND (CA’ NOGHERA, VENICE, ITALY) Riassunto. Predazione di uccelli acquatici su Bufotes viridis (Laurenti, 1768) nella zona umida di Ca’ Vallesina (Ca’ Noghera, Venezia). Viene riportata per la prima volta la predazione di rospo smeraldino da parte di due specie di uccelli acquatici, Bubulcus ibis e Threskiornis aethiopicus, in una piccola zona umida lungo il margine nordoccidentale della Laguna di Venezia. Summary. Predation instances on the green toad by two waterbird predators, Bubulcus ibis and Threskiornis aethiopicus, are reported for the first time in a small wetland along the northwestern border of the Lagoon of Venice (NE-Italy). Keywords: Bufotes viridis, predation, waterbirds, Bubulcus ibis, Threskiornis aethiopicus. Reference: Novarini N., Stival E., 2017. Wading birds predation on Bufotes viridis (Laurenti, 1768) in the Ca’ Vallesina wetland (Ca’ Noghera, Venice, Italy). Bollettino del Museo di Storia Naturale di Venezia, 67: 71-75. INTRODUCTION Anuran amphibians are typical intermediate predators in the food-chain of wetlands, being active consumers of invertebrates, especially insects, and occasionally small vertebrates, as well as prey themselves of invertebrates, fishes, other amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, including man. Egrets, ibises and other wading birds often share the same wetland habitat with amphibians and are major (though opportunistic) predators of anurans, especially of the palatable ranids (KABISCH & BELTER, 1968; COOK, 1987; DUELLMAN & TRUEB, 1994; TOLEDO et al., 2007; WELLS, 2007). A wide number of species across almost all anuran families, however, contain toxic and/or distasteful secretions in their skin glands, with bufonids generally included among the least palatable species, either as adults and larvae (LUTZ, 1971; DUELLMAN & TRUEB, 1994; TOLEDO & JARED, 1995; GUNZBURGER & TRAVIS, 2005).