Margins and Marginality in Fifteenth-Century London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central London Plan Bishopsgate¬Corridor Scheme Summary

T T T T D S S S R Central London Plan EN H H H H H RE G G BETHNAL SCLATER S Bishopsgate¬corridor Scheme Summary I T H H ShoreditchShoreditch C Key T I HHighigh StreetStreet D E Bus gate – buses and cyclists only allowed R O B through during hours of operation B H R W R OR S I I Q Q SH C IP C S K Section of pavement widened K ST N T E Y O S T L R T A L R G A U Permitted turns for all vehicles DPR O L I N M O B L R N O F S C O E E S P ST O No vehicular accessNSN except buses P M I A FIF E M Email feedback to: T A E streetspacelondon@tfl.gov.uk G R S C Contains Ordnance Survey data LiverpoolLiverpool P I © Crown copyright 2020 A SStreettreet O L H E MoorgateM atete S ILL S T I ART E A B E T RY LANAN R GAG E R E O L M T OOO IVE * S/BS//B onlyoonlyy RP I OO D M L S O T D S LO * N/BN//B onlyoonlyy L B ND E S O ON S T RNR W N E A E LL X T WORM A WO S OD HOUH T GATEG CA T T M O R S R E O U E H S M NDN E G O T I T I A LE D H O D S S EL A G T D P M S B I A O P E T H R M V C . -

SHOREDITCH HIGH STREET, HACKNEY P91/LEN Page 1 Reference Description

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 SAINT LEONARD, SHOREDITCH: SHOREDITCH HIGH STREET, HACKNEY P91/LEN Reference Description Dates PARISH RECORDS - LMA holdings Parish Records P91/LEN/0001 Monthly list of burial dues Apr 1703-Apr Gives details of persons buried, i.e., name, 1704 man/woman, address, old/new ground, and dues. Paper cover is part of undertaking by Humphry Benning and John Milbanke to pay John Chub for fish taken to Portugal from Newfoundland, John -- of Plymouth, Devon, and Hen------ of Looe, Cornwall, having interest in the ship 28 Nov [1672] P91/LEN/0002 CALL NUMBER NO LONGER USED P91/LEN/0003 Draft Vestry minute book Mar 1833-Aug 1837 P91/LEN/0004 Notices of meetings of Vestry and of Trustees Jul 1779-Jan of the Poor, with note of publication 1785 P91/LEN/0005 Notices of meetings of Vestry, for various Sep 1854-Feb purposes 1856 P91/LEN/0006 Register of deeds, etc. belonging to the parish Dec 1825 and to charities Kept in boxes in the church. Includes later notes of those borrowed and returned P91/LEN/0007 Minute Book of Trustees May 1774-Aug Under Act for the better relief and employment 1778 of the poor within the parish of St Leonard, Shoreditch P91/LEN/0008 Minute Book of Trustees Aug 1778-May Under Act for the better relief and employment 1785 of the poor within the parish of St Leonard, Shoreditch P91/LEN/0009 Minute Book of Trustees Jun 1785-Jun Under Act for the better relief and employment 1792 of the poor within the parish of St Leonard, Shoreditch LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 SAINT LEONARD, SHOREDITCH: -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title In danger of undoing: The Literary Imagination of Apprentices in Early Modern London Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1fx380bc Author Drosdick, Alan Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California In danger of undoing: The Literary Imagination of Apprentices in Early Modern London by Alan J. Drosdick A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Joel B. Altman, Chair Professor Jeffrey Knapp Professor Albert Russell Ascoli Fall 2010 Abstract In danger of undoing: The Literary Imagination of Apprentices in Early Modern London by Alan J. Drosdick Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Joel B. Altman, Chair With the life of the apprentice ever in mind, my work analyzes the underlying social realities of plays such as Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday, Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, Jonson, Chapman, and Marston’s Eastward Ho!, and Shakespeare’s Henriad. By means of this analysis, I reopen for critical investigation a conventional assumption about the mutually disruptive relationship between apprentices and the theater that originated during the sixteenth century and has become a cliché of modern theater history at least since Alfred Harbage’s landmark Shakespeare’s Audience (1941). As a group, apprentices had two faces in the public imagination of renaissance London. The two models square off in Eastward Ho!, where the dutiful Golding follows his master’s orders and becomes an alderman, while the profligate Quicksilver dallies at theaters and ends up in prison. -

Committee(S) Dated: Planning and Transportation

Committee(s) Dated: Planning and Transportation 23rd June 2020 Subject: Public Delegated decisions of the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director Report of: For Information Chief Planning Officer and Development Director Summary Pursuant to the instructions of your Committee, I attach for your information a list detailing development and advertisement applications determined by the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director or those so authorised under their delegated powers since my report to the last meeting. In the time since the last report to Planning & Transportation Committee Thirty-Nine (39) matters have been dealt with under delegated powers. Sixteen (16) relate to conditions of previously approved schemes. Six (6) relate to works to Listed Buildings. Two (2) applications for Non-Material Amendments, Three (3) applications for Advertisement Consent. One (1) Determination whether prior app required, Two (2) applications for works to trees in a conservation area, and Nine (9) full applications which, including Two (2) Change of Uses and 396sq.m of floorspace created. Any questions of detail arising from these reports can be sent to [email protected]. Details of Decisions Registered Address Proposal Applicant/ Decision & Plan Number & Agent name Date of Ward Decision 20/00292/LBC 60 Aldersgate (i) Replacement of single Mackay And Approved Street London glazed, steel framed Partners Aldersgate EC1A 4LA double height windows 04.06.2020 with double glazed aluminium framed windows (north and south facing elevations, first and second sub-podium levels) (ii) Retention of existing frames and replacement of single glazing with double glazing (north and south facing elevations, first sub-podium level) (iii) Retention of frames and replacement double glazed units (south and west facing elevations, second sub-podium level). -

Igniting Change and Building on the Spirit of Dalston As One of the Most Fashionable Postcodes in London. Stunning New A1, A3

Stunning new A1, A3 & A4 units to let 625sq.ft. - 8,000sq.ft. Igniting change and building on the spirit of Dalston as one of the most fashionable postcodes in london. Dalston is transforming and igniting change Widely regarded as one of the most fashionable postcodes in Britain, Dalston is an area identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. It is located directly north of Shoreditch and Haggerston, with Hackney Central North located approximately 1 mile to the east. The area has benefited over recent years from the arrival a young and affluent residential population, which joins an already diverse local catchment. , 15Sq.ft of A1, A3000+ & A4 commercial units Located in the heart of Dalston and along the prime retail pitch of Kingsland High Street is this exciting mixed use development, comprising over 15,000 sq ft of C O retail and leisure space at ground floor level across two sites. N N E C T There are excellent public transport links with Dalston Kingsland and Dalston Junction Overground stations in close F A proximity together with numerous bus routes. S H O I N A B L E Dalston has benefitted from considerable investment Stoke Newington in recent years. Additional Brighton regeneration projects taking Road Hackney Downs place in the immediate Highbury vicinity include the newly Dalston Hackney Central Stoke Newington Road Newington Stoke completed Dalston Square Belgrade 2 residential scheme (Barratt Road Haggerston London fields Homes) which comprises over 550 new homes, a new Barrett’s Grove 8 Regents Canal community Library and W O R Hoxton 3 9 10 commercial and retail units. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

City, St Katharine Cree

CITY, ST KATHARINE CREE This church was known as St. Katharine de Christ Church at Alegate in 1280. The 80 ft high tower was built in 1504 at the cost of Sir John Percivall, merchant tailor, at the west end of the south aisle. A spiral staircase in the north-west corner gives access to the ringing chamber. A small bell hangs in the cupola built 1776. This bell and the front five bells are listed. The gilded cock weather-vane is possibly from the previous church. There is a Renaissance sundial of 1662 on the south wall of the tower. Bells were in existence during the reign of King Edward VI. There was a ring of five bells when the Rambling Ringers rang two six-scores of Grandsire in 1733 but they proved difficult to ring. In 1754 the frame was rebuilt and the bells were hung so as to produce an anti-clockwise circle. In 1842 a bell was recast by Thomas Mears II - old bell 11cwt and 21lbs. Meat and poultry were sold in the nearby Leadenhall Market in the 1600’s when the women wore white aprons hence the inclusion in the ‘Oranges and Lemons’ rhyme as, Maids in White Aprons. Source: K E Campbell, A brief history and account of St Katharine Cree church revised 1999; Charles W Pearce, Old London City churches their organs, organists and musical associations; Basil F L Clarke, Parish churches of London 1966 p 22; Mervyn Blatch, A guide to London’s churches 1979, pp 93-4; City of London Corporation, City of London churches (n.d.), pp 14-5; Whitechapel Bell Foundry records; Christopher J Pickford; W T Cook, Ringing world March 2, 1973, p 163; Ringing world March 23, 1945, p 119. -

Prisoners in LUDGATE Prison., in the City of London

1565 ] iliomas Nasb, fornterly, and late of Braintree, in tbc county SECOND NOTICE. of Essex, calmjtft-Kiaker. George Yoomans, lat,«of No. 7, John-street, CrutcUod-friar;*,' ChUrles Moore, formerly, anulrtte of Peckham, in the county and forrurrly' of No, 2, Hart-street, both in the city ef of Surrey, carpenter-. • London, taylor. Thomas SiavthaiVt, -i'lrt-mefjy of Seal, and late t>f Greenwich, .Tames Devilt, late of No. 73, Snowhill, and formerly of No. iwthetminiry wf iCcjrt, tdge-^tool-niaher. 75, Lombard-street, both iu the city of London^ trust*- 'William Masters, formerly of •Bond-str-cet, imtl Iste of Dover- nvaker. stri-ct, Saint Geortje's-fielas, Sbitthwsurh, «hoe-u«iker. James-Keys, late of No. 7, Red Lion-court, Charter-house- tsamrtel Meek,formerly, and late of Chuvch-stetjtJt, Horseley- lane, in -the county of Middlesex, and of Newgate-market, dow.ii, alid of Webb-Street,, Bcrnwndsey, both iu tlie county London, aud formerly of No. 1, Red Lion-court, Cock- of Surrey., 'cooper. lane, Giltspur-street, London, poulterer. ^heopbilus Jftnstun, formerly oT Clafh-Fair, W«st. Smith field, Anu Longs^aff, late of Prujean-square, Oldibailey, and for- -and of Totteubarn-TOuTt-roatl, both in the Bounty of merly of-the Belle Sauvage*yard, Ludgate-hill, both in the "Middlesex, tailor. city of London, widow. 3eseph Hy&m, formerly rif'tber-ttytrf Bristol, and late of William Drought, late of Red Lion-street, .Olerkenwell, and • A'bergavemry, iuthe county of Mouiuouth, shopkeeper aud formerly of Baltic-street, Old-street, both in the county of jeweller. -

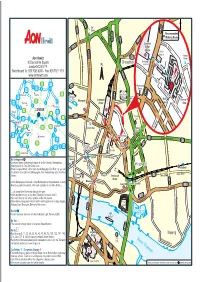

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

Ludgate Circus, London, EC4 to Let Prominent E Class Shop Close to St Paul’S Cathedral

RETAIL PROPERTY PARTICUL ARS Ludgate Circus, London, EC4 To Let Prominent E Class Shop close to St Paul’s Cathedral. Ground & Basement 857 SQ FT 7 Ludgate Circus London EC4M 7LF OFFICE PROPERTY PARTICUL ARS OFFICE PROPERTY P Location Description The Ground floor and Basement currently have E1 use. This prominent building occupies the South West quadrant of Ludgate Circus on the intersections of Farringdon and New Bridge Street (the A201, leading to Net internal areas: Blackfriars Bridge) with Fleet Street/Ludgate Hill, historically the main connection Ground floor 310 sq. ft between the City of London and Westminster. Having St Paul’s Cathedral in site Basement 547 sq. ft complements this building with high pedestrian flow. Total 857 sq. ft The property has excellent transport links with City Thameslink Station one minute away, and Blackfriars (Circle & District Lines) and St Paul’s (Central Line) Use a short walk away. E class (formerly A1 retail). VIEW MAP https://tinyurl.com/yaob892w Terms Lease: A new Full Repairing and Insuring Lease for a Term of 6 years and 11 months to be contracted outside of the Landlord & Tenant Act 1954, part II (as amended). Rent: Offers invited in region of £66,500 per year. Service Charge: (including 12.5% management fees) estimated at £902 per year. Insurance: estimated at £1,553 for period 24/06/2020 - 23/06/2021. Please note that a Rent Collection fee of 5% is applied to this particular property. Business Rates Interested parties are advised to make their own enquiries with the Local Authority. Professional Costs Each party to pay their own legal costs in this transaction. -

Naval Dockyards Society

20TH CENTURY NAVAL DOCKYARDS: DEVONPORT AND PORTSMOUTH CHARACTERISATION REPORT Naval Dockyards Society Devonport Dockyard Portsmouth Dockyard Title page picture acknowledgements Top left: Devonport HM Dockyard 1951 (TNA, WORK 69/19), courtesy The National Archives. Top right: J270/09/64. Photograph of Outmuster at Portsmouth Unicorn Gate (23 Oct 1964). Reproduced by permission of Historic England. Bottom left: Devonport NAAFI (TNA, CM 20/80 September 1979), courtesy The National Archives. Bottom right: Portsmouth Round Tower (1843–48, 1868, 3/262) from the north, with the adjoining rich red brick Offices (1979, 3/261). A. Coats 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the MoD. Commissioned by The Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England of 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, EC1N 2ST, ‘English Heritage’, known after 1 April 2015 as Historic England. Part of the NATIONAL HERITAGE PROTECTION COMMISSIONS PROGRAMME PROJECT NAME: 20th Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth (4A3.203) Project Number 6265 dated 7 December 2012 Fund Name: ARCH Contractor: 9865 Naval Dockyards Society, 44 Lindley Avenue, Southsea, PO4 9NU Jonathan Coad Project adviser Dr Ann Coats Editor, project manager and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Davies Editor and reviewer, project executive and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Evans Devonport researcher David Jenkins Project finance officer Professor Ray Riley Portsmouth researcher Sponsored by the National Museum of the Royal Navy Published by The Naval Dockyards Society 44 Lindley Avenue, Portsmouth, Hampshire, PO4 9NU, England navaldockyards.org First published 2015 Copyright © The Naval Dockyards Society 2015 The Contractor grants to English Heritage a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, perpetual, irrevocable and royalty-free licence to use, copy, reproduce, adapt, modify, enhance, create derivative works and/or commercially exploit the Materials for any purpose required by Historic England.