Space Oddities: Aliens, Futurism and Meaning in Popular Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

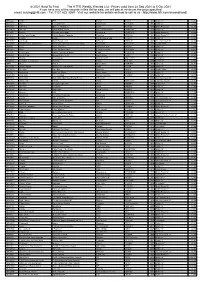

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates Gary M. Bogers University of Central Florida Part of the Music Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bogers, Gary M., "Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 511. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/511 MUSIC AND THE PRESIDENCY: HOW CAMPAIGN SONGS SOLD THE IMAGE OF PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES by GARY MICHAEL BOGERS JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Music Performance in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Dr. Scott Warfield Co-chairs: Dr. Alexander Burtzos & Dr. Joe Gennaro ©2019 Gary Michael Bogers Jr. ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I will discuss the importance of campaign songs and how they were used throughout three distinctly different U.S. presidential elections: the 1960 campaign of Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy against Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon, the 1984 reelection campaign of President Ronald Wilson Reagan against Vice President Walter Frederick Mondale, and the 2008 campaign of Senator Barack Hussein Obama against Senator John Sidney McCain. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

Legacy of a Mad Scientist

i JOHN CARRICK “First, I'd like to know, do any of you have experience in the martial arts?" About half the hands went up. Ashley didn't raise her hand, despite two previous summers of similar courses; she did not count herself as experienced. "Now, how many of you have been hit, hard, in the face?" Sihing Shou asked. At first several hands went up, but some were timid, uncertain. "I mean really hit hard; bloody nose, fat lip, black eye. How many?" Only a few hands remained aloft. Shou pointed to one boy and asked, "Who hit you?" "My brother hits me all the time," he said, pointing at his brother, standing a few spaces away. Shou and several others laughed. Ashley noticed that the boy, however, was not laughing. She suspected he was very interested in how to put a stop his brother’s dominance. "And you?" Shou gestured to another boy. "My father," came the answer. Shou pointed again. "A kid in my class." "Has anyone here ever been hit while in the ring?" Shou asked. All the hands went down. "When you are in a fight, if you are ever in a fight, you must fight for your life. It will be at that moment when you are weak, tired, probably very hurt, that is when you must act to save your life. We will help you get to that place and teach you how to think while you're there." Instructor Shou walked along the front of the room. "Someone may come; an outlaw, the government, a king, they may take all of your possessions. -

OZ 17 Richard Neville Editor

University of Wollongong Research Online OZ magazine, London Historical & Cultural Collections 12-1968 OZ 17 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1968), OZ 17, OZ Publications Ink Limited, London, 48p. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon/17 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] OZ 17 Description Editor: Richard Neville. Design: Jon Goodchild. Writers: Andrew Fisher, Ray Durgnat, David Widgery, Angelo Quattrocchi, Ian Stocks. Artists: Martin Sharp, John Hurford, Phillipe von Mora. Photography: Keith Morris Advertising: Felix Dennis, REN 1330. Typesetting: Jacky Ephgrave, courtesy Thom Keyes. Pushers: Louise Ferrier, Felix Dennis, Anou. This issue produced by Andrew Fisher. Content: Louise Ferrier colour back issue/subscription page. Anti-war montage. ‘Counter-Authority’ by Peter Buckman. ‘The alH f Remarkable Question’ - Incredible String Band lyric and 2p illustration by Johnny Hurford. Martin Sharp graphics. Flypower. Poverty Cooking by Felix and Anson. ‘The eY ar of the Frog’ by Jule Sachon. ‘Guru to the World’ - John Wilcock in India. ‘We do everything for them…’ - Rupert Anderson on homelessness. Dr Hipocrates (including ‘inflation’ letter featured in Playpower). Homosexuality & the law. David Ramsay Steele on the abolition of Money. ‘Over and Under’ by David Widgery – meditations on cultural politics and Jeff uttN all’s Bomb Culture. A Black bill of rights – LONG LIVE THE EAGLES! ‘Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Mall’ - the ethos of the ICA. Graphic from Nottingham University. Greek Gaols. Ads for Time Out and John & Yoko’s Two Virgins. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: the Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa

VOL. 42, NO. 1 ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 1998 Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: The Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa INGRID BIANCA BYERLY DUKE UNIVERSITY his article explores a movement of creative initiative, from 1960 to T 1990, that greatly influenced the course of history in South Africa.1 It is a movement which holds a deep affiliation for me, not merely through an extended submersion and profound interest in it, but also because of the co-incidence of its timing with my life in South Africa. On the fateful day of the bloody Sharpeville march on 21 March 1960, I was celebrating my first birthday in a peaceful coastal town in the Cape Province. Three decades later, on the weekend of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in February 1990, I was preparing to leave for the United States to further my studies in the social theories that lay at the base of the remarkable musical movement that had long engaged me. This musical phenomenon therefore spans exactly the three decades of my early life in South Africa. I feel privi- leged to have experienced its development—not only through growing up in the center of this musical moment, but particularly through a deepen- ing interest, and consequently, an active participation in its peak during the mid-1980s. I call this movement the Music Indaba, for it involved all sec- tors of the complex South African society, and provided a leading site within which the dilemmas of the late-apartheid era could be explored and re- solved, particularly issues concerning identity, communication and social change. -

Native Instruments Releases the Second Installment in the EVERYBODY DJ Video Series

Native Instruments releases the second installment in the EVERYBODY DJ video series Dance music pioneer A Guy Called Gerald discusses the cultural link between new technology and the evolution of electronic music Berlin, September 18, 2014 – Native Instruments today continues the EVERYBODY DJ video series with the second installment featuring electronic music legend A Guy Called Gerald. The video features Gerald describing how innovative technology plays an important role in defining DJ culture and how mobile apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone are creating new performance possibilities and diversifying relationships to digital music. An icon in his own league, A Guy Called Gerald has been an instrumental figure in the development of techno, acid house, jungle, and drum and bass in the UK since the late 1980s. The video captures Gerald’s view on the close relationship between technology and electronic music – reflecting on previous audio limitations with vinyl, and how digital technology has changed how he listens to, DJs, and creates music. Filmed in London at the premier of RELEASE, a documentary on House Shuffling in Britain, the video shows Gerald as he explains why the physical manipulation of waveforms on apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone has given rise to completely new ways of DJing. Gerald can be seen mixing, beat jumping, and loop slicing live with TRAKTOR DJ for iPad – a tool that has had a particular impact on his DJing. Still underway, the first video in the EVERYBODY DJ series introduced the MIX. WIN. BERLIN! competition where Native Instruments asks “What would you play?” Anyone can enter to win a VIP weekend in Berlin by recording and uploading a mix to Mixcloud using TRAKTOR DJ, and tagging it with the #whatwouldyouplay hashtag. -

The Prayer of Jabez by Bruce Wilkingson Lesson V

1 The Prayer of Jabez By Bruce Wilkingson Lesson V “Keeping The Legacy Safe” “O That You Would Keep Me From Evil” 1 Chronicles 4:9-10 9) And Jabez was more honourable than his brethren: and his mother called his name Jabez, saying, Because I bare him with sorrow. 10) And Jabez called on the God of Israel, saying, Oh that thou wouldest bless me indeed, and enlarge my coast, and that thine hand might be with me, and that thou wouldest keep me from evil, that it may not grieve me! And God granted him that which he requested. Introduction: 1. A caption read “Sometimes you can afford to come in second. Sometimes you cannot.” a. This was placed under a Roman Gladiator who was in trouble. b. Here is the picture i. The Gladiator has dropped his sword ii. The enraged lion is in mid lunge with his jaws wide iii. The crowd is on their feet watching in horror as the panic-stricken gladiator tries to flee. Note: This is a horrible time to come in second. 2. Jabez had asked for supernatural blessing, influence, and power. a. Many people think that they can jump into any arena with any lion, “and win.” b. Some people with the hand of God upon them might pray “Lord, Keep me through evil,” but not Jabez. i. Jabez prayed “Keep me from evil.” ii. The best way to defeat a roaring lion is to stay out of the arena. 2 iii. Therefore Jabez prayed “Keep me from evil” which was a prayer that is saying: “God, keep me out of the fight.” 3. -

FOR CODESRIA Anyidoho/Madame Virginie Niang Sept 17-19

1 THE IMPORTANCE OF AFRICAN POPULAR MUSIC STUDIES FOR GHANAIAN/AFRICAN STUDENTS by John Collins INTRODUCTION A) The role of popular music and mass entertainment in the independence struggle and the consequent importance of local popular performance in the vision of pioneer African leaders: i.e. a mass music for a mass party (eg highlife as the product of the ‘veranda boy’ class). Thus the state support of popular as well as traditional and western type art/religious music sectors by the pioneering leaders Nkrumah, Nyere, Sekou Toure, President Keita. Their approach can therefore be considered as tri-musical B) The failure of this tri-musical approach being transmitted into the Ghanaian tertiary education system. This became rather bi-musical; i.e. the training of students only in traditional African and imported western art idioms C) Some reasons for this intellectual university hostility to popular music/culture 1) imported elitist, Marxist and Frankfurt School ideas concerning the ephemeral, frivolous, low status and inconsequential nature (cf. high art) of popular music and performance. 2) Residual African traditional attitudes towards professional musicians. Low regard and apprehension of such indigenous professional traditional groups as West African jalis/griots, praise drummers and goje players D) The negative consequences of the narrow bi-musical approach has effected both the university students and the evolution of local musical forms such as highlife music and the concert party. It fosters elitist attitudes by students who do not consider the creative role of the masses and intermediate classes important in musical development. It has in a lack of intellectual input into local popular music: few books and biographies on the topic, no intellectual input into it. -

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French