On the Lived Experience of Truth in an Era of Educational Reform: Co-Responding to Anti-Intellectualism ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education James Magrini College of Dupage, [email protected]

College of DuPage [email protected]. Philosophy Scholarship Philosophy 7-1-2012 Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education James Magrini College of DuPage, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/philosophypub Part of the Education Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Magrini, James, "Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education" (2012). Philosophy Scholarship. Paper 30. http://dc.cod.edu/philosophypub/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Scholarship by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education James M. Magrini Existentialism, and specifically phenomenology, in qualitative educational research, tends to be misunderstood. There are many reasons for this, not the least of which is that scholars/researchers writing in the field often emulate and imitate the dense writing styles of philosophical forerunners in phenomenology such as Hegel, Brentano, Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty. Thus the writing is beyond the comprehension of many education professionals and practitioners. Existentialism and phenomenology need not be highly complex. Here I provide a summary of existentialism and phenomenology in accessible terms so that educators might see the potential this type of philosophy holds for enhancing our educational endeavors. 1. Existentialism is a modern philosophy emerging (existence-philosophy) from the 19th century, inspired by such thinkers as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. Unlike traditional philosophy, which focuses on “objective” instances of truth, existentialism is concerned with the subjective, or personal, aspects of existence. -

Descartes' Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View

R ené Descartes (1596-1650) is generally regarded as the “father of modern philosophy.” He stands as one of the most important figures in Western intellectual history. His work in mathematics and his writings on science proved to be foundational for further development in these fields. Our understanding of “scientific method” can be traced back to the work of Francis Bacon and to Descartes’ Discourse on Method. His groundbreaking approach to philosophy in his Meditations on First Philosophy determine the course of subsequent philosophy. The very problems with which much of modern philosophy has been primarily concerned arise only as a consequence of Descartes’thought. Descartes’ philosophy must be understood in the context of his times. The Medieval world was in the process of disintegration. The authoritarianism that had dominated the Medieval period was called into question by the rise of the Protestant revolt and advances in the development of science. Martin Luther’s emphasis that salvation was a matter of “faith” and not “works” undermined papal authority in asserting that each individual has a channel to God. The Copernican revolution undermined the authority of the Catholic Church in directly contradicting the established church doctrine of a geocentric universe. The rise of the sciences directly challenged the Church and seemed to put science and religion in opposition. A mathematician and scientist as well as a devout Catholic, Descartes was concerned primarily with establishing certain foundations for science and philosophy, and yet also with bridging the gap between the “new science” and religion. Descartes’ Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View 1) Descartes’ disbelief in authoritarianism: Descartes’ belief that all individuals possess the “natural light of reason,” the belief that each individual has the capacity for the discovery of truth, undermined Roman Catholic authoritarianism. -

Vietnamese Existential Philosophy: a Critical Reappraisal

VIETNAMESE EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY: A CRITICAL REAPPRAISAL A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Hi ền Thu Lươ ng May, 2009 i © Copyright 2009 by Hi ền Thu Lươ ng ii ABSTRACT Title: Vietnamese Existential Philosophy: A Critical Reappraisal Lươ ng Thu Hi ền Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Lewis R. Gordon In this study I present a new understanding of Vietnamese existentialism during the period 1954-1975, the period between the Geneva Accords and the fall of Saigon in 1975. The prevailing view within Vietnam sees Vietnamese existentialism during this period as a morally bankrupt philosophy that is a mere imitation of European versions of existentialism. I argue to the contrary that while Vietnamese existential philosophy and European existentialism share some themes, Vietnamese existentialism during this period is rooted in the particularities of Vietnamese traditional culture and social structures and in the lived experience of Vietnamese people over Vietnam’s 1000-year history of occupation and oppression by foreign forces. I also argue that Vietnamese existentialism is a profoundly moral philosophy, committed to justice in the social and political spheres. Heavily influenced by Vietnamese Buddhism, Vietnamese existential philosophy, I argue, places emphasis on the concept of a non-substantial, relational, and social self and a harmonious and constitutive relation between the self and other. The Vietnamese philosophers argue that oppressions of the mind must be liberated and that social structures that result in violence must be changed. Consistent with these ends Vietnamese existentialism proposes a multi-perspective iii ontology, a dialectical view of human thought, and a method of meditation that releases the mind to be able to understand both the nature of reality as it is and the means to live a moral, politically engaged life. -

A Hermeneutic Phenomenological Inquiry Into the Lived Experiences of Taiwanese Parachute Students

A HERMENEUTIC PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY INTO THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF TAIWANESE PARACHUTE STUDENTS By Benjamin T. OuYang Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillm ent Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2004 Advisory Committee: Professor Francine Hultgren, Chair and Advisor Associate Professor Jing Lin Ms. Su -Chen Mao Associate Professor Marylu McEwen Dr. Maria del Carmen Torres -Queral Copyright by Benjamin T. OuYang 2004 ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A HERMENEUTIC PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY INTO THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF TAIWANESE PARACHUTE STUDENTS. Benjamin T. OuYang, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertatio n directed by: Dr. Francine H. Hultgren Department of Education Policy and Leadership The purpose of this study is to understand the lived experiences of Taiwanese parachute students, so named because of their being sent to study in the United States, fr equently unaccompanied by their parents. Significant themes are revealed through hermeneutic phenomenological methodology and developed using the powerful metaphor of landing. Seven parachute students took part in several in -depth conversations with the researcher about their experiences living in the States, immersed in the English language and the American culture. Their stories are reflective accounts, which when coupled with literary and philosophic sources, reveal the essence of this experience of living in a foreign land. Voiced by teenage and young adult parachute students, the metaphor of landing as shown in their search for establishing a home and belonging, is the slate for the writing of this work’s main themes. The research opens up to a deeper understanding of this phenomenon in such themes as foreignness, landing and surveying the area; lost in the language; homesickness; and trying to establish friendships. -

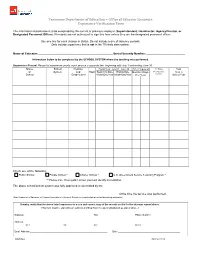

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Heidegger Letter on Humanism Translation GROTH

Martin Heidegger LETTER ON "HUMANISM"*1 Translated by Miles Groth, PhD We still by no means think decisively enough about the essence of action. One knows action only as the bringing about of an effect, the effectiveness of which is assessed according to its usefulness. However, the essence of action is perfecting <something>. Perfecting means to unfold something in the fullness of its essence, <and in so doing> to bring it forth, producere. Therefore, <the> perfectible is actually only that which already is. Yet that which above all "is," is be[-ing]. Thinking perfects the relation of be[-ing] to the essence of man. It does not make or effect this relation. Thinking only bears it as that which is handed over to be[-ing]. This bearing consists in the fact that in thinking be[-ing] comes into language. Language is the place for be[- ing]. Man lives by its accommodation. Those who are thoughtful and those who are poetic are the overseers of these precincts. Overseeing for them is perfecting the evidence of be[-ing], insofar as they bring this up in their utterances and save it in language. Thinking does not in that way just turn into action in the sense that an effect issues from it or that it is applied <to something>. Thinking acts in that it thinks. This <kind of> action is presumably the simplest and at the same time the highest because it concerns the relation of be[-ing] to man. But all effecting 1Heidegger's marginal notes in his copies of the various editions of the lecture are included in GA 9. -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Èthos and Ek-Sistence Humanism As an Explicitly Ethical Preoccupation in Heidegger’S Letter on Humanism

Èthos and ek-sistence Humanism as an explicitly ethical preoccupation in Heidegger’s Letter on Humanism Thesis for obtaining a “Master of Arts” degree in philosophy Radboud University Nijmegen Name: Senne van den Berg Student number: s4433068 Supervisor: prof. dr. G. J. van der Heiden Second examiner: dr. V.L.M. Vasterling Date: 30-09-2020 I hereby declare and assure that I, Senne van den Berg, have drafted this thesis independently, that no other sources and/or means other than those mentioned have been used and that the passages of which the text content or meaning originates in other works - including electronic media - have been identified and the sources clearly stated. Place: Nijmegen, date: 30-09-2020. 2 Èthos and ek-sistence Humanism as an explicitly ethical preoccupation in Heidegger’s Letter on Humanism To stand under the claim of presence is the greatest claim made upon the human being. It is “ethics." 1 – Martin Heidegger Senne van den Berg Abstract: Martin Heidegger’s 1947 Letter on Humanism takes up a significant place in the oeuvre of the German philosopher. This important text is often discussed for two topics: Heidegger’s discussion of humanism, and his discussion of ethics as ‘abode.’ However, these two topics are being discussed isolated from each other, which obscures the inherent relation there is between the two for Heidegger. This paper will show that Heidegger’s discussion of humanism in the Letter is decisively shaped by his ethical preoccupations. I. Heidegger, humanism and ethics Martin Heidegger’s 19472 Letter on Humanism takes up a significant place in the oeuvre of the German philosopher. -

“Modern” Philosophy: Introduction

“Modern” Philosophy: Introduction [from Debates in Modern Philosophy by Stewart Duncan and Antonia LoLordo (Routledge, 2013)] This course discusses the views of various European of his contemporaries (e.g. Thomas Hobbes) did see philosophers of the seventeenth century. Along with themselves as engaged in a new project in philosophy the thinkers of the eighteenth century, they are con- and the sciences, which somehow contained a new sidered “modern” philosophers. That might not seem way of explaining how the world worked. So, what terribly modern. René Descartes was writing in the was this new project? And what, if anything, did all 1630s and 1640s, and Immanuel Kant died in 1804. these modern philosophers have in common? By many standards, that was a long time ago. So, why is the work of Descartes, Kant, and their contempor- Two themes emerge when you read what Des- aries called modern philosophy? cartes and Hobbes say about their new philosophies. First, they think that earlier philosophers, particu- In one way this question has a trivial answer. larly so-called Scholastic Aristotelians—medieval “Modern” is being used here to describe a period of European philosophers who were influenced by time, and to contrast it with other periods of time. So, Aristotle—were mistaken about many issues, and modern philosophy is not the philosophy of today as that the new, modern way is better. (They say nicer contrasted with the philosophy of the 2020s or even things about Aristotle himself, and about some other the 1950s. Rather it’s the philosophy of the 1600s previous philosophers.) This view was shared by and onwards, as opposed to ancient and medieval many modern philosophers, but not all of them. -

SPINOZA's ETHICS: FREEDOM and DETERMINISM by Alfredo Lucero

SPINOZA’S ETHICS: FREEDOM AND DETERMINISM by Alfredo Lucero-Montaño 1. What remains alive of a philosopher's thought are the realities that concern him, the problems that he addresses, as well as the questions that he poses. The breath and depth of a philosopher's thought is what continues to excite and incite today. However, his answers are limited to his time and circumstances, and these are subject to the historical evolution of thought, yet his principal commitments are based on the problems and questions with which he is concerned. And this is what resounds of a philosopher's thought, which we can theoretically and practically adopt and adapt. Spinoza is immersed in a time of reforms, and he is a revolutionary and a reformer himself. The reforming trend in modern philosophy is expressed in an eminent way by Descartes' philosophy. Descartes, the great restorer of science and metaphysics, had left unfinished the task of a new foundation of ethics. Spinoza was thus faced with this enterprise. But he couldn't carry it out without the conviction of the importance of the ethical problems or that ethics is involved in a fundamental aspect of existence: the moral destiny of man. Spinoza's Ethics[1] is based on a theory of man or, more precisely, on an ontology of man. Ethics is, for him, ontology. He does not approach the problems of morality — the nature of good and evil, why and wherefore of human life — if it is not on the basis of a conception of man's being-in-itself, to wit, that the moral existence of man can only be explained by its own condition. -

Heidegger's Black Notebooks and the Future of Theology

HEIDEGGER’S BLACK NOTEBOOKS AND THE FUTURE OF THEOLOGY Edited by Mårten Björk and Jayne Svenungsson Heidegger’s Black Notebooks and the Future of Theology Mårten Björk · Jayne Svenungsson Editors Heidegger’s Black Notebooks and the Future of Theology Editors Mårten Björk Jayne Svenungsson University of Gothenburg Centre for Theology and Religious Gothenburg, Sweden Studies Lund University Lund, Sweden ISBN 978-3-319-64926-9 ISBN 978-3-319-64927-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64927-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017949186 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.