Learning by Doing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cgm V2n2.Pdf

Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Table of Contents 8 24 Reset 4 Communist Letters From Space 5 News Roundup 7 Below the Radar 8 The Road to 300 9 Homebrew Reviews 11 13 MAMEusements: Penguin Kun Wars 12 26 Just for QIX: Double Dragon 13 Professor NES 15 Classic Sports Report 16 Classic Advertisement: Agent USA 18 Classic Advertisement: Metal Gear 19 Welcome to the Next Level 20 Donkey Kong Game Boy: Ten Years Later 21 Bitsmack 21 Classic Import: Pulseman 22 21 34 Music Reviews: Sonic Boom & Smashing Live 23 On the Road to Pinball Pete’s 24 Feature: Games. Bond Games. 26 Spy Games 32 Classic Advertisement: Mafat Conspiracy 35 Ninja Gaiden for Xbox Review 36 Two Screens Are Better Than One? 38 Wario Ware, Inc. for GameCube Review 39 23 43 Karaoke Revolution for PS2 Review 41 Age of Mythology for PC Review 43 “An Inside Joke” 44 Deep Thaw: “Moortified” 46 46 Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Editor-in-Chief Chris Cavanaugh [email protected] Managing Editors Scott Marriott [email protected] here were two times a year a kid could always tures a firsthand account of a meeting held at look forward to: Christmas and the last day of an arcade in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Skyler Miller school. If you played video games, these days writer's initial apprehension of attending. [email protected] T held special significance since you could usu- Also in this issue you may notice our arti- ally count on getting new games for Christmas, cles take a slight shift to the right in the gaming Writers and Contributors while the last day of school meant three uninter- timeline. -

Caesar 3 Download Mac

Caesar 3 Download Mac 1 / 4 Caesar 3 Download Mac 2 / 4 3 / 4 This seems to be a Power-PC Mac OS game, so beware as 'EKO' mentioned, there might be options that allow you to use it.. External linksCaptures and Snapshots Screenshots from MobyGames comComments and reviewsFija2017-10-263 points One of the best games I've ever played.. Is there any 'No CD patch' as available on Windows PC?Saumitra2014-11-025 points Mac version.. There is not too much conquest (e g Command and Conquer gameplay), as you can only assert direct control over your military units.. i can't figure how to make share folder or what everd2015-12-020 point got this message: Can't open aplication “Caesar™ III Installer” due to Classic environment is no longer compatible. How you accomplish this is up to you Gain wealth and power, make a career out of pleasing the emperor, battle barbarians and repel invaders, or concentrate on building the next Eternal City.. That's a kick in the teeth from Amazon Amazon com: Caesar III (Mac): Video Games $14 for the PC version, $120 for the Mac version. caesar caesar, caesar salad, caesar zeppeli, caesar meaning, caesar northwestern, caesar cipher, caesar pronunciation, caesar dressing, caesar cut, caesar palace, caesars atlantic city, caesars palace, caesar jojo, caesar caesar, caesars rewards, caesarstone com website and buy the game You automatically get when creating an account 12 free GOG games added to your account from which 11 for the Mac, so you have nothing to loose, only to receive!Use this CrossTie to install the game in Crossover and start the fun! Make sure Crossover is installed before downloading/running the CrossTie. -

Current, April 24, 2017

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers Spring 4-24-2017 Current, April 24, 2017 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, April 24, 2017" (2017). Current (2010s). 262. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/262 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 50 Issue 1532 The Current April 24, 2017 UMSL’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWS UMSL’s Fiscal Future: Panel UMSL Chief of Police Discusses Possible $17 Million Forrest Van Ness to Deficit for Fiscal Year 2018 Retire in May Lori Dresner News Editor handful of students gathered A in the SGA Chambers on April 19 to hear panelists discuss the in- ternalities and externalities of the budget deficit and projections for the upcoming fiscal year at the Uni- versity of Missouri–St. Louis. The panelists included Chief Fi- nancial Officer Rick Baniak, Dean of the College of Business Charles Hoffman, Chancellor Tom George, and Associated Students of the Uni- versity of Missouri (ASUM) rep- resentative Jordan Lucas, senior, economics. Baniak said that administrators LORI DRESNER / THE CURRENT LORI LORI DRESNER / THE CURRENT LORI and faculty have been working col- Students listen to panelists discuss the challenges of fiscal year 2017. Captain Marisa Smith, Chief of UMSL Police and Director of Institutional Safety Forrest lectively over the past year to ana- Van Ness, and Captain Dan Freet in the UMSL Police Station. -

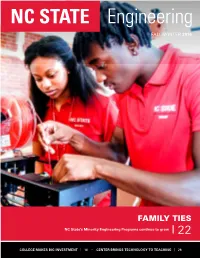

FAMILY TIES NC State’S Minority Engineering Programs Continue to Grow 22

FALL/WINTER 2016 FAMILY TIES NC State’s Minority Engineering Programs continue to grow 22 COLLEGE MAKES BIG INVESTMENT | 16 § CENTER BRINGS TECHNOLOGY TO TEACHING | 28 PUTTING PLANS IN MOTION FALL/WINTER 2016 Since its establishment in 1887, the campus of what is The plan is for the entire College to eventually move now called North Carolina State University has been to Centennial Campus, save for the nuclear reactor in contents in a constant state of change and growth, with ideas Burlington Labs. That’s staying put. for expansion and improvement always in the heads FEATURES of university leaders and on the pages of planning On page 20 and 21, you can learn about the fate of documents. Today is no exception. the buildings that long lined ‘Engineering Row’ (now 14 IN OUR LABS Explore the spaces where our engineering faculty members work, starting with an anechoic chamber. 16 FORWARD MOTION The College plans to invest $250 million in infrastructure and faculty hiring over the next five years. 22 FAMILY TIES 14 The College’s Minority Engineering Programs continue to grow. 26 NSF ERC UPDATES The College’s two National Science Foundation Engineering Research Centers are reinventing the power grid and developing wearable health monitoring systems. 28 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM The Center for Educational Informatics is changing the way we learn. 22 DEAN Dr. Louis A. Martin-Vega OFFICE OF THE DEAN College of Engineering ADVISORY BOARD Campus Box 7901, NC State University Dr. John Gilligan, Executive Associate Dean of Engineering Raleigh, NC 27695-7901 Brian Campbell, Assistant Dean for Development and College 919.515.2311 Relations, Executive Director of the NC State Engineering Foundation, www.engr.ncsu.edu Inc. -

The Possibility Analysis of Esports Becoming an Olympic Sport

The possibility analysis of Esports becoming an Olympic sport Yucong Wu Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in Sports Coaching and Management 2019 Author(s) Yucong Wu Degree programme Degree Programme in sport management Report/thesis title Number of pages and The possibility analysis of Esports becoming an Olympic sport appendix pages 33+2 Abstract Since Esports became a demonstration sport of the Jakarta Asian games, people have been wondering whether Esports will become an official event in the Olympics and Asian games. But as the events for the 2024 Paris Olympics and the 2022 Asian games in Hangzhou were announced, Esports is not included. The purpose of this study is to find out the factors of Esports becoming an Olympic sport and discuss the feasibility of turning Esports into an Olympic project. This study analyzes the popularity and social recognition of Esports, the defected audience advantages of Esports and how Esports match Olympic values. According to data and literature analysis, some Esports have undesirable elements that do not accord with the Olympic values, but they also have positive elements. The high popularity of Esports among young people is in line with the IOC's desire to attract more young people to the games. However, since the penetration rate of other age groups is comparatively low, Esports is less popular than the new sports in the next two Olympic Games, and the general concept of Esports and video games are not yet clear. The short life and high commercialization are usually regarded as the main defects of Esports, while the latter actually plays a positive role in driving host countries to embrace Esports. -

12.2% 118000 130M Top 1% 154 4400

We are IntechOpen, the world’s leading publisher of Open Access books Built by scientists, for scientists 4,400 118,000 130M Open access books available International authors and editors Downloads Our authors are among the 154 TOP 1% 12.2% Countries delivered to most cited scientists Contributors from top 500 universities Selection of our books indexed in the Book Citation Index in Web of Science™ Core Collection (BKCI) Interested in publishing with us? Contact [email protected] Numbers displayed above are based on latest data collected. For more information visit www.intechopen.com Chapter 4 Cryptocurrencies in the Ludic Economies: The Case of Contemporary Game Cultures Leonardo José Mataruna-dos-SantosJosé Mataruna-dos-Santos and Vanissa WanickVanissa Wanick Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.80950 Abstract Games have their own economic models. Today, players can not only collect digital currencies, but they can also use real currencies to buy virtual goods. Business models in games such as freemium and in-app purchases, for example, sustain this structure. Within this context, there is also the expansion of models outside the game realm like eSports, which happens in the form of tournaments. With this, there is constant exchange of value that emerges from games, which could also include the use of cryptocurren- cies. In this chapter, we give an overview of the current state of the art of economic models within games and eSports. The current chapter aims to situate and analyse the application of these business models derived from games, e-sport and the future of ludic economies. -

Downloaded 09/28/21 04:05 PM UTC Esports Result Higher Prevalence Problematic Gaming?

REVIEW ARTICLE Journal of Behavioral Addictions 8(3), pp. 384–394 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.46 First published online September 25, 2019 Will esports result in a higher prevalence of problematic gaming? A review of the global situation THOMAS CHUNG*, SIMMY SUM, MONIQUE CHAN, ELY LAI and NANLEY CHENG Student Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR, China (Received: August 23, 2018; revised manuscript received: November 27, 2018; second revised manuscript received: April 8, 2019; accepted: July 24, 2019) Background and aims: Video gaming is highly prevalent in modern culture, particularly among young people, and a healthy hobby for the majority of users. However, in recent years, there has been increasing global recognition that excessive video gaming may lead to marked functional impairment and psychological distress for a significant minority of players. Esports is a variant of video gaming. It is a relatively new phenomenon but has attracted a considerable number of followers across the world and is a multimillion dollar industry. The aim of this briefing paper is to review the global situation on esports and related public health implications. Methods: A non-systematic review was conducted. Information obtained from the Internet and PubMed was collated and presented as genres of games, varieties and magnitudes of impacts, popularity, fiscal impact in monetary terms, government involvement, and public health implications. Results: There are several different kinds of esports but there was no clear categorization on the genre of games. Many tournaments have been organized by gaming companies across the world with huge prize pools, and some of these events have government support. -

Ancient Greece and Rome in Videogames: Representation, Player Processes, and Transmedial Connections

Ancient Greece and Rome in Videogames: Representation, Player Processes, and Transmedial Connections Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ross Clare September 2018 Abstract Videogames are a hugely popular entertainment medium that plays host to hundreds of different ancient world representations. They provide very distinctive versions of recreated historical and mythological spaces, places, and peoples. The processes that go into their development, and the interactive procedures that accompany these games, must therefore be equally unique. This provides an impetus to both study the new ways in which ancient worlds are being reconfigured for gameplayers who actively work upon and alter them, and to revisit our conception of popular antiquity, a continuum within popular culture wherein ancient worlds are repeatedly received and changed in a variety of media contexts. This project begins by locating antiquity within a transmedial framework, permitting us to witness the free movement of representational strategies, themes, subtexts and ideas across media and into ancient world videogames. An original approach to the gameplay process, informed by cognitive and memory theory, characterises interaction with virtual antiquity as a procedure in which the receiver draws on preconceived notions and ideas of the ancient past to facilitate play. This notion of “ancient gameplay” as a reception process fed by general knowledges, previous pop-cultural engagements, and dim resonances of antiquity garnered from broad, informal past encounters allows for a wide, all-encompassing study of “ancient games”, the variety of sources they (and the player) draw upon, and the many experiences these games offer. -

Pride, Not Money, the Spur to Egames King 8 September 2016, by Pirate Irwin

Pride, not money, the spur to eGames King 8 September 2016, by Pirate Irwin It is certainly a money-spinning industry and its revenue last year was more than $700 million, $320 million of that in Asia. Money, though, is not what is driving King. "I come from this world of traditional sport," King told AFP after appearing on a panel at the Sport Industry Breakfast Club, supported by MP & Silva. "What I saw in eSports was it has been all about prize money and I was concerned it would end up like poker. "If you have children playing it its (the money) not The eGames were showcased in Rio during the the right thing so like in traditional sport tennis has Olympics the Davis Cup and golf the Ryder Cup, where the players don't play for money, I wondered where was the equivalent in eSports. Golf has the Ryder Cup, tennis the Davis Cup and now the fast-growing eSports will have the eGames in Pyeongchang in 2018, the main mover behind it, Chester King, told AFP. The 44-year-old Englishman—chief executive of the International eGames Group—said his wish was for national pride to be at stake rather than it being based around prize money, as is the case with most eSports events. ESports, in which sedentary competitors play video games, would not be a winner with former International Olympic Committee (IOC) president Jacques Rogge, who introduced the Youth Olympic Games primarily because he wanted to Players of eSports train for hours each day get young people enthused about taking exercise. -

(Intellectual P Technology) from Un and BA.LLB from Bha E-Mail

ELK ASIA PACIFIC JOURNAL OF COMPUTER SCIENCE AND INFORMATION SYSTEM ISSN 2349-9392 (Online); DOI: 10.16962/EAPJMRM/issn. 2349-9392/2015; Volume 5 Issue 1 (2019) www.elkjournals.com TREATMENT AND REGULATION OF e-SPORTS Riya Gulati Paralegal at Law Offices of Caro Kinsella and Youth Ambassador for the ONE Campaign, Ireland. LL.M (Intellectual Property & Information Technology) from University College Dublin and BA.LLB from Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The E-Sportsports industry has seen prodigious upsurge over the years both in terms of revenue and viewership. The three radical chunks that contributed to the esports industry’s rise as the succeeding major spectator sport are as follows: streamed competitions with methodical leagues, proficient contenders can be viewed from anywhere, and live events in top-tier offline sports venues. E-sports has been globally embraced but alike traditional sports, it is girdled with challenges. This paper aims to provide the pith of E-Sports by exploring the crucial issues involved in the cyber sports such as: whether eSports is contemplated as a sport or not?, lack of proper governance and regulatory framework, intellectual property rights issues, exploitation of players, gambling and cheating. It will also accentuate on the necessity to have a proper regulation of eSports by pivoting on the policy recommendations. “What makes the eSports industry such a captivating market is its ability to take video games- ideally played on a couch with a bag of chips and soft drink- to an arena suited for basketball or hockey”- Ben Charlson Key Words: Electronic sports, competitive gaming, eGames, cybersports, eGamers, traditional sport. -

Materiały Edukacyjne Dla Początkujących| Numer 1 (2017)

BIULETYN E-SPORTOWY MATERIAŁY EDUKACYJNE DLA POCZĄTKUJĄCYCH | NUMER 1 (2017) Materiały zebrane i opracowane przez: Stowarzyszenie Sportów Elektronicznych (eSports Association) z siedzibą w Katowicach PL 40-013 ul. Staromiejska 5/8 tel. 515 099 193 KRS: 0000643710 NIP: 9542770816 REGON: 36582255800000 BIULETYN E-SPORTOWY | MATERIAŁY EDUKACYJNE DLA POCZĄTKUJĄCYCH | NR 1 Drodzy Czytelnicy, mam przekonanie graniczące z pewnością, że każda czytająca te słowa osoba choć przez chwilę miała już styczność ze światem e-sportu. Czy to widząc zdjęcia kilometrowych kolejek przed finałami Intel Extreme Masters w katowickim Spodku, czy też słysząc informację o zakontraktowaniu gracza FIFA 2017 przez warszawską Legię, czy choćby zerkając na monitor oglądającego właśnie transmisję z turnieju syna/córki/młodszego rodzeństwa. Jako eSports Association chcemy, aby ogromny potencjał e-sportu dostrzegły także osoby jak dotąd niezwiązane z tą branżą. Są to między innymi rodzice i nauczyciele, których podopieczni marzą o staniu się profesjonalnym zawodnikiem w – przykładowo – Counter-Strike: Global Offensive czy League of Legends. Niniejszy biuletyn będzie spełniał właśnie taką rolę – w comiesięcznych wydaniach postaramy się przedstawić zagadnienia związane ze sportem elektronicznym i jego dyscyplinami w przystępny sposób, stopniowo poszerzając poruszane wątki. Pierwsze wydanie biuletynu zawiera kompendium e-sportowej wiedzy dla początkujących. Znajdują się w nim odpowiedzi na podstawowe pytania dotyczące sportów elektronicznych oraz relacja z wizyty w Zespole Szkół nr 1 w Piekarach Śląskich, w którym od września ubiegłego roku funkcjonuje klasa e-sportowa. Jesteśmy określani Naszym celem jest sprawienie, by fenomen sportów jako‚ największa elektronicznych stał się nie tylko zrozumiały, lecz przede wszystkim nisza na świecie. pasjonujący. Najwyższa pora na poznanie tego, czym zachwycają “ się miliony młodych ludzi na całym świecie! Nie jesteśmy nią. -

Activision Blizzard Wants Esports to Be Big League 4 November 2016, by Glenn Chapman

Activision Blizzard wants eSports to be big league 4 November 2016, by Glenn Chapman grow to 427 million people over the coming three years, according to Activision. A strong focus of the Overwatch League is to provide competitive gamers with the kind of status typically given to professional athletes in traditional sports. "We want them to have that kind of recognition for their achievements, and also financial rewards," Kotick said of eSports contenders. Teams in the league will share in revenue from sources such as licensing, broadcast rights, and ticket sales, according to Activision. Activision Blizzard CEO, Bobby Kotick said the launch of a team-based shooter game called "Overwatch", aims to Late last year, Activision Blizzard launched a create greater prominence for eSports division devoted to competitive gaming. It has since acquired live eSports event titan star Major League Gaming and launched Call of Duty World League based on a blockbuster shooter franchise. Activision Blizzard is creating an eSports league of its own with competitive play of team-based Overwatch League's opening season was slated for shooter game "Overwatch," and a goal of building next year. professional stars—possibly with big-league payouts. The Blizzard Entertainment video game released about five months ago already boasts more than 20 The US video game giant on Friday announced the million players who have been vying against one creation of an Overwatch League, saying it will let another on an amateur level. teams share in money generated by the latest entry in the booming trend of computer game play "Overwatch has such a special place for me; I as spectator sport.