Fainstein - Fragmented States and Pragmatic Improvements 1 AESOP Young Academics Booklet Project Conversations in Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability, Hegemony, and Urban Policy in Calgary by Tom Howard BA

From Risky Business to Common Sense: Sustainability, Hegemony, and Urban Policy in Calgary by Tom Howard B.A. (with distinction), University of Calgary, 2010 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2015 © Tom Howard 2015 ABSTRACT Recent years have seen the City of Calgary adopt a suite of sustainability policies in a bid to shift its received trajectory of sprawling urban development towards eco-conscious alternatives. But where sustainable urban development is typically rendered as a consensus-driven project portending mutual benefits for a given locality, the historical adoption of sustainability policies in Calgary has been characterized by waves of conflict and controversy which have allegedly watered down the City’s policy objectives. Rather than evaluating the technical merits of individual policies against ‘best practice’-type standards, this thesis argues that the meanings and implications of particular policy paradigms – such as Calgary’s move towards sustainability – must be found in both the specific institutional configurations in which policies are formed and the political-economic conditions to which they respond. This thesis explores these institutional pressures and conjunctural forces through a historical analysis of several key moments in the emergence and evolution of sustainability-oriented policy in Calgary. Chapter 1 establishes context for this inquiry, while Chapter 2 formulates a theoretical framework by synthesizing neo-Marxian interpretations of local environmental policy and recent innovations in the field of ‘policy mobilities’ with the work of Antonio Gramsci, particularly related to his conception of hegemony. -

Cities for People, Not for Profit

CITIES FOR PEOPLE, NOT FOR PROFIT The worldwide financial crisis has sent shock waves of accelerated economic restructuring, regulatory reorganization, and sociopolitical conflict through cities around the world. It has also given new impetus to the struggles of urban social movements emphasizing the injustice, destructiveness, and unsustainability of capitalist forms of urbanization. This book contributes analyses intended to be useful for efforts to roll back contemporary profit-based forms of urbanization, and to promote alternative, radically democratic, and sustainable forms of urbanism. The contributors provide cutting-edge analyses of contemporary urban restructuring, including the issues of neoliberalization, gentrification, colonization, “creative” cities, architecture and political power, sub-prime mortgage foreclosures, and the ongoing struggles of “right to the city” movements. At the same time, the book explores the diverse interpretive frameworks – critical and otherwise – that are currently being used in academic discourse, in political struggles, and in everyday life to decipher contemporary urban transformations and contestations. The slogan, “cities for people, not for profit,” sets into stark relief what the contributors view as a central political question involved in efforts, at once theoretical and practical, to address the global urban crises of our time. Drawing upon European and North American scholarship in sociology, politics, geography, urban planning, and urban design, the book provides useful insights and perspectives for citizens, activists, and intellectuals interested in exploring alternatives to contemporary forms of capitalist urbanization. Neil Brenner is Professor of Urban Theory at the Graduate School of Design, Harvard University. He formerly served as Professor of Sociology and Metropolitan Studies at New York University. -

The Housing Crisis and the Rise of the Real Estate State

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2019 The Housing Crisis and the Rise of the Real Estate State Samuel Stein CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/552 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Mary and Andrew Bennetts, Flickr Hudson Yards in New York City. Cost to taxpayers in the form of bond offerings, tax breaks, and direct subsidies = $5.6 billion, dwarfing the incentives offered to Amazon in the failed incentives package to locate its second headquarters in Long Island City, New York. NLFXXX10.1177/1095796019864098New Labor ForumStein 864098research-article2019 New Labor Forum 1 –8 The Housing Crisis and the Rise Copyright © 2019, The Murphy Institute, CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies of the Real Estate State Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1095796019864098 10.1177/1095796019864098 journals.sagepub.com/home/nlf Samuel Stein1 Keywords urban planning, housing, gentrification, real estate, organizing Around the world, more and more money is equity firms like Blackstone—now the world’s being invested in real estate, the business of largest landlord.4 building, buying, and renting land and property. Global real estate is now worth $217 trillion, In 2016, a record 37 percent of thirty-six times the value of all the gold ever home sales were made to absentee mined. -

Cuz Potter Professor, Division of International Studies, Korea University

Cuz Potter Professor, Division of International Studies, Korea University Personal Data Address: International Studies Hall, Room 522, Korea University,Anam-dong, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, 136-701, Republic of Korea Phone: (82) 2 3290 2427 email: [email protected] Education Columbia Ph.D. in urban planning (October 2010) University NewYork, NY,U.S.A. Thesis: Boxed In: How Intermodalism Enabled Destructive Interport Competition Advisors: Profs. Peter Marcuse and Susan Fainstein Master of Science in Urban Planning (May 2003) Thesis: Bits of Diversity: A pilot study for the application of a hierarchical, entropic measure of economic diversity to regional economic growth and stability Master of International Affairs (May 2003) Concentration: Urban and regional development with a focus on developing countries Sogang Korean language (Sept. 1996 to May 1997) University Seoul, Korea Tufts Bachelor of Arts, English literature (May 1989) University Medford, MA, U.S.A. University Exchange semester (October 1987 to June 1988) ofYork Heslington, England, U.K. Publications Potter, Cuz, and Jinhee Park. 2021. “A multitude of models: transferring knowledge of the Korean development experience.” Chap. 7 in Exporting Urban Korea? Reconsidering the Korean Urban Development Experience, edited by Se Hoon Park, Hyun Bang Shin, and Hyun Soo Kang.Taylor & Francis Ltd. isbn: 9781000292725. Potter, Cuz. 2021. “The Deliberative Option: The Theoretical Evolution of Citizen Participation in Risk Management and Possibilities for East Asia.” In Risk Management in East Asia, edited by Yijia Jing, Jung-Sun Han, and Keiichi Ogawa, 93–117. Systems and Frontier Issues. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4586-7. Kim, Jeeyeop, Cuz Potter, and A-ra Cho. -

The Great Refusal: Herbert Marcuse and Contemporary Social Movements

Excerpt • Temple University Press 1 Bouazizi’s Refusal and Ours Critical Reflections on the Great Refusal and Contemporary Social Movements Peter N. Funke, Andrew T. Lamas, and Todd Wolfson The Dignity Revolution: A Spark of Refusal n December 17, 2010, in a small rural town in Tunisia, an interaction that happens a thousand times a day in our world—the encounter Obetween repression’s disrespect and humanity’s dignity—became a flashpoint, igniting a global wave of resistance. On this particular day, a police officer confiscated the produce of twenty-six-year-old street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi and allegedly spit in his face and hit him. Humiliated and in search of self-respect, Bouazizi attempted to report the incident to the municipal government; however, he was refused an audience. Soon there- after, Bouazizi doused himself in flammable liquid and set himself on fire. Within hours of his self-immolation, protests started in Bouazizi’s home- town of Sidi Bouzid and then steadily expanded across Tunisia. The protests gave way to labor strikes and, for a few weeks, Tunisians were unified in their demand for significant governmental reforms. During this heightened period of unrest, police and the military responded by violently clamping down on the protests, which led to multiple injuries and deaths. And as is often the case, state violence intensified the situation, resulting in mounting pressure on the government. The protests reached their apex on January 14, 2011, and Tunisian president Ben Ali fled the country, ending his twenty- three years of rule; however, the demonstrations continued until free elec- tions were declared in March 2011. -

DISORIENTATION GUIDE Change in Our Political and Economic TABLE of CONTENTS Systems

PLANNERS NETWORK STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES The Planners Network is an association of professionals, activists, academics, and students involved in physical, social, economic, and environmental planning in urban and rural areas, who promote fundamental DISORIENTATION GUIDE change in our political and economic TABLE OF CONTENTS systems. We believe that planning should be a I. Introduction tool for allocating resources and 2 Welcome to the Disorientation Guide developing the environment to 3 Planners Network From the Beginning eliminate the great inequalities of 4 A Little Bit of History: Some Events Influencing wealth and power in our society, rather the Development of Planning in the U.S. than to maintain and justify the status quo. We are committed to opposing II. Politics and Planning: The Processes racial, economic, and environmental that Shape Our Space injustice and discrimination by gender 6 Planning and Neoliberalism and sexual orientation. We believe that 8 Anti-Neoliberal Planning with a Human Rights planning should be used to assure Framework adequate food, clothing, housing, 9 Infiltration from the North: Canadians Tackle medical care, jobs, safe working Planning in America conditions, and a healthful environment. We advocate public III. Education or Indoctrination? Shaping responsibility for meeting these needs, Your Own Progressive Planning Education because the private market has proven 10 Cracks in the Foundation of Traditional Planning incapable of doing so. 12 The Need for Techno-Progressive Planners 13 Media and Education Resource List We seek to be an effective political 17 How Planners Can Be Activists for Change: The and social force, working with other Sustainable South Bronx Project progressive organizations to inform 19 What Advice do you Have for Planners Who public opinion and public policy and Want to Work from Within a Progressive Political to provide assistance to those seeking Framework? to understand, control, and change the 20 Planning is Organizing: An Interview with Ken forces which affect their lives. -

Resistance, Rebellion and Revolt!

OCIALiT SCHOLARS CONFERENCE Resistance, Rebellion and Revolt! April 18, 19 & 20, 1986 The 4th Annual Boro of Manhattan Community College, CUNY, 199 Chambers Street, New York City FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 7-10 pm 9:30 am-lO pm 9:30 am-6 pm Resistance, Rebellion and Revolt! A broad range of academics and social activists have gathered for a 4th Annual Socialist Scholars Conference on Friday through Sunday, April 18-20 at the Boro of Manhattan Community College. This year's theme of Resistance, Rebellion and Revolt focuses upon a century of mass workers movements: 100th Anniversary of the Haymarket Riots, 75th Anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire (which helped galvanize the women's working-class movement here in New York City), the 50th Anniversary of the great sit-down strikes which helped found the CIO, the 50th Anniversary of the Spanish Civil War, and the 30th Anniversary of the Hungarian Revolt. This year we are commemorating the millions who have fought and died in the real socialist struggle, the continual revolt from below. CHILDCARE AVAILABLE Saturday 9:00 am - 5:00 pm Sunday 9:00 am - 5:00 pm Children must toilet trained and at least three years old. ROOM N312 The Graduate School and University Center of the City University of New York Ph.D. Program in Sociology I Box 375 Graduate Center: 33 West 42 Street, New York, N.Y. 10036-8099 212 790-4320 To Our Fellow Participants: Socialism, in the multifaceted forms it has adopted, has inspired a vast number of social movements in a wide range of countries. -

“YOU MUST REMEMBER THIS” Abraham (“Abe”) Edel

MATERIAL FOR “YOU MUST REMEMBER THIS” Abraham (“Abe”) Edel (6 December 1908 – 22 June 2007) “Twenty-Seven Uses of Science in Ethics,” 7/2/67 Abraham Edel, In Memoriam, by Peter Hare and Guy Stroh Abraham Edel, 1908-2007 Abraham Edel was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on December 6, 1908. Raised in Yorkton, Canada with his older brother Leon who would become a biographer of Henry James, Edel studied Classics and Philosophy at McGill University, earning a BA in 1927 and an MA in 1928. He continued his education at Oxford where, as he recalled, “W.D. Ross and H.A. Prichard were lecturing in ethics, H.W.B. Joseph on Plato, and the influence of G. E. Moore and Bertrand Russell extended from Cambridge. Controversy on moral theory was high. The same was true of epistemology, where Prichard posed realistic epistemology against Harold Joachim who was defending Bradley and Bosanquet against the metaphysical realism of Cook Wilson.” He received a BA in Litterae Humaniores from Oxford in 1930. In that year he moved to New York City for doctoral studies at Columbia University, and in 1931 began teaching at City College, first as an assistant to Morris Raphael Cohen. F.J.E. Woodbridge directed his Columbia dissertation, Aristotle’s Theory of the Infinite (1934). This monograph and two subsequent books on Aristotle were influenced by Woodbridge’s interpretation of Aristotle as a philosophical naturalist. Although his dissertation concerned ancient Greek philosophy, he was much impressed by research in the social sciences at Columbia, and the teaching of Cohen at City College showed him how philosophical issues lay at the root of the disciplines of psychology, sociology, history, as well as the natural sciences. -

MA in Urban Studies

The City University of New York The School of Professional Studies at the Graduate School and University Center Proposal to Establish a Master of Arts in Urban Studies Anticipated Start Fall 2012 Approved by the School of Professional Studies Curriculum Committee December 8, 2011 Approved by the School of Professional Studies Governing Council January 5, 2012 John Mogulescu Senior University Dean for Academic Affairs and Dean, School of Professional Studies 212-794-5429 Phone 212-794-5706 Fax [email protected] George Otte Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, School of Professional Studies 212-817-7145 Phone 212-889-2460 Fax [email protected] Brian A. Peterson Associate Dean for Administration and Finance, School of Professional Studies 212-817-7259 Phone 212-889-2460 Fax [email protected] U Dean‘s Signature ___________________________________________________ Table of Contents ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................... 2 SED APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF A NEW PROGRAM ............................................................ 3 NARRATIVE .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Purpose and Goals .................................................................................................................................... 7 Need and Justification .............................................................................................................................. -

A Reevaluation of Marcuse's Philosophy of Technology

A Reevaluation of Marcuse's Philosophy of Technology Michael Kidd Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Tasmania, July, 2013. 1 A Reevaluation of Marcuse's Philosophy of Technology Michael Kidd 2 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material which infringes copyright. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. 3 Abstract This thesis provides a reevaluation of Herbert Marcuse's philosophy of technology. It argues that rather than offering an abstract utopian or dystopian account of technology, Marcuse's philosophy of technology can be read as a cautionary approach developed by a concrete philosophical utopian. The strategy of this thesis is to reread Marcuse's key texts in order to challenge the view that his philosophy of technology is abstractly utopian. Marcuse is no longer a fashionable figure and there has been little substantive literature devoted to the problem of the utopian character of his philosophy of technology since the works of Douglas Kellner and Andrew Feenberg. This thesis seeks to reposition Marcuse as a concrete philosophical utopian. It then reevaluates his philosophy of technology from this standpoint and suggests that it may have relevance to some contemporary debates. -

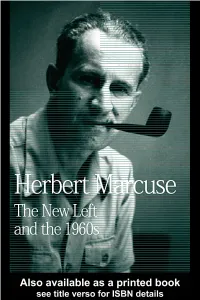

THE NEW LEFT and the 1960S COLLECTED PAPERS of HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED by DOUGLAS KELLNER

THE NEW LEFT AND THE 1960s COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three THE NEW LEFT AND THE 1960s Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA HERBERT MARCUSE (1898–1979) is an internationally renowned philosopher, social activist and theorist, and member of the Frankfurt School. He has been remembered as one of the most influential social critical theorists inspiring the radical political movements in the 1960s and 1970s. Author of numerous books including One-Dimensional Man, Eros and Civilization, and Reason and Revolution, Marcuse taught at Columbia, Harvard, Brandeis University and the University of California before his death in 1979. DOUGLAS KELLNER is George F. Kneller Chair in the Philosophy of Education at U.C.L.A. He is author of many books on social theory, politics, history and culture, including Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism, Media Culture and Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity. His Critical Theory and Society: A Reader, co-edited with Stephen Eric Bronner, and recent book Media Spectacle, are also published by Routledge. THE NEW LEFT AND THE 1960s HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Three Edited by Douglas Kellner First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004 © 2005 Peter Marcuse Selection, editorial matter and introduction © 2005 Douglas Kellner Preface © 2005 Angela Y. -

The Just City

THE JUST CITY: A CRITICAL DISCUSSION ON SUSAN FAINSTEIN’S FORMULATION Adel Khosroshahi Supervisor: Stefano Moroni Faculty of Architecture and Society Polytechnic University of Milan March 2015 CONTENTS 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2 The Just City: Susan Fainstein’s Formulation .......................................................... 4 2.1 From Communicative Planning to Capabilities Approach ..................................... 8 2.1.1 False Consciousness and Communicative Planning ........................................ 9 2.1.2 Relationship Between Inclusive Deliberation, Equity and Justice ................ 10 2.1.3 The Capabilities Approach ............................................................................. 14 2.2 Qualities of the just city and their relationship ..................................................... 16 2.2.1 Democracy ..................................................................................................... 17 2.2.2 Diversity ......................................................................................................... 18 2.2.3 Equity ............................................................................................................. 21 2.3 From New York to London to the Just City of Amsterdam ................................... 23 2.3.1 New York ....................................................................................................... 23 2.3.2 London ..........................................................................................................