How to Use the Digital Language Vitality Scale the Digital Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodiek Oktober-November-December 2007

België - Belgique P.B.-P.P. 2000 Antwerpen 1 BC 9497 PERIODIEK DRIEMAANDELIJKS TIJDSCHRIFT VAN HET VLAAMS GENEESKUNDIGENVERBOND 62ste jaargang Oktober – November – December 2007 Nr. 4 AFGIFTEKANTOOR: 2000 ANTWERPEN 1 Inhoud VOORWOORD ................................................................................................................................................... 3 GESCHIEDENIS VAN DE GENEESKUNDE.................................................................................................4 VAN TABOE NAAR VRIJHEID.................................................................................................................................................................... 4 BALANS............................................................................................................................................................... 8 HET VERHAAL VAN POLITICI DIE WEIGEREN HUN MACHT TE GEBRUIKEN*................................................................ 8 FORUM ..............................................................................................................................................................10 IN NAGEDACHTENIS VAN COLLEGA KENENS..............................................................................................................................10 SOCIALE ZEKERHEID VAN HUISARTSEN BLIJFT ONDERMAATS!..........................................................................................10 ZET VLAANDEREN OP HET INTERNET! ............................................................................................................................................11 -

Briefing Note on .AFRICA (Dotafrica)

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA DEPARTEMENT OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND ENERGY INFORMATION SOCIETY DIVISION BRIEFING NOTE ON .AFRICA (Read “DOT AFRICA) 1 May-2011 Overview of Domain Names When you use the Web or send an e-mail message, you use a domain name to do it. For example, the URL "http://www.african-union.org" contains the domain name african-union.org. So does the e-mail address "[email protected]" Human-readable names like "African-union.org" are easy for people to remember, but they don't do machines any good. All of the machines use names called IP addresses to refer to one another. For example, the machine that humans refer to as "www.african-unions.org" has the IP address 70.42.251.42. An often-used analogy to explain the Domain Name System (DNS) is that it serves as the phone book for the Internet by translating human-friendly computer hostnames into IP addresses. For example, the domain name www.embassy.com translates to the addresses 192.0.32.10 In general, the Domain Name System also stores other types of information, such as the list of mail servers that accept email for a given Internet domain. It also reflect an identity and belonging to a geographic area and / or community Generic Top Level Domains (gTLDs) The first-level set of domain names are called top-level domains (TLDs) and the first of these are referred to as generic top-level domains (gTLDs). These include domains such as the well-known .com (dot com), .net (dot net) and. -

Geographic Names at the Top Level ICANN

Geographic Names at the Top Level ICANN August 2017 Prepared by Managing Director David Fairman and Associate Julia Golomb Consensus Building Institute This report summarizes the history and background of the geoTLD issue; the goals, process and proceedings of the ICANN59 cross-community public sessions; and CBI’s substantive observations and process options for consideration. History and Background ICANN policy development and advice on the use of geographic names as TLDs: There is a substantial ICANN history regarding the use of geographic names as top-level domains (geoTLDs).1 During the early development of the Internet in the mid-1980s, Jon Postel at ARPA established the use of the ISO 3166-1 list of two-letter country codes as the source for country-code TLDs (ccTLDs) in countries outside the US. In the first and second rounds of TLD expansion in 2000 and 2003, geoTLDs were not expressly prohibited, and two were created (.asia and .cat). In the process of establishing the Applicant Guidebook (AGB) for the third round of gTLD expansion, during the years 2007-2012, the Generic Names Supporting Organization (GNSO) and the Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC) proposed different guidelines for the use of geographic names, including but not limited to country and territory names. In 2007, the GNSO Reserved Names Working Group recommended that – with the sole exception of all two-character TLDs, which were reserved for ccTLDs – geographic names should not be excluded, but that governmental interests be protected via challenge mechanisms in the application process. This recommendation was adopted by the GNSO- led Policy Development Process (PDP) on the Introduction of New Generic Top-Level Domains. -

A Nosa Rede Decembro 2019

Decembro do 2019 Galicia: Da 5G aos xemelgos dixitais colexio oficial A NOSA REDE enxeñeiros de telecomunicación 2 galicia Decembro do 2019 A N O S A R E D E Presidente Julio Sánchez Agrelo Director Xavier Alcalá Navarro Comité de redacción Escola de Enxeñaría de Telecomunicación Campus Lagoas-Marcosende s/n Xavier Alcalá Navarro 36310 Vigo - Pontevedra Edita de Lorenzo Rodríguez T: 986 465 234 F: 886 125 996 Ricardo Fernández Fernández [email protected] Julio Sánchez Agrelo Coordinación e deseño Síguenos en: Ana Isabel Becerra Illanes ISSN: 1699-3861 A revista A Nosa Rede non se fai necesariamente responsable da opinión dos seus colaboradores. D I R E C T O R I O P R O F E S I O N A L D E G A B I N E T E S E E N X E Ñ E I R O S D E T E L E C O M U N I C A C I Ó N JESÚS AMIEIRO BECERRA SMARTEL GESTIÓN Y SERVICIOS, S.L. ACBIA SOLUCIONES S.L.U. EVENTYAM INGENIEROS, S.L. Nº de Colexiado: 13432 MANUEL BERMEJO PLANA FAUSTINO CASTRO SANJORGE MARÍA E. BALTAR CARRILLO O Porriño - Pontevedra Nº de colexiado: 8681 Nº Colegiado: 12363 Nº de colexiada: 6470 Teléfono: 630615609 Teléfono: 644302013 Movil:677163247 Teléfono: 615 663 964 [email protected] Sanxenxo (Pontevedra) [email protected] / [email protected] Rúa Tarragona 39, 5ºD. 36211. Vigo. Pontevedra. http://ww.jesusamieiro.com [email protected] Consult. Estratégica, [email protected] Informes periciales, consultoría TIC, www.smartelgestion.com Conectividad/Comunicaciones, A.Técnica www.eventyam.com software a medida, ICT Radiocomunicaciones, informática, TDT, Estudo do electromagnetismo en zonas laborais Gap-fillers, proyectos y direcciones de obra ALFONSO MOREDO ARAÚJO según RD 299/2016. -

(GDD) General Operations Handbook for Registry Operators

Global Domains Division (GDD) General Operations Handbook for Registry Operators Version 1.1 15 August 2018 ICANN | Global Domains Division (GDD) General Operations Handbook for Registry Operators | August 2018 | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. OVERVIEW 3 Welcome 3 Revisions in This Release 4 Domain Name Industry Ecosystem 4 II. INTERFACES TO REGISTRY OPERATORS 5 Global Domains Division (GDD) 5 ICANN Contractual Compliance 6 Organizations for Registry Operators 6 III. ONGOING REGISTRY OPERATIONS 7 Commonly Provided Registry Services 7 IV. USEFUL TOOLS, REGISTRY RESOURCES, AND ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 9 Useful Tools 9 Registry Resources on icann.org 10 Additional Information 11 V. REGISTRY OPERATOR OBLIGATIONS 12 Continuous Obligations 12 Daily Obligations 14 Weekly Obligations 14 Monthly Obligations 14 Quarterly Obligations 15 Annual Obligations 15 This GDD General Operations Handbook is provided for general education and informational purposes only, and is not intended to modify, alter, amend or otherwise supplement the rights, duties, liabilities or obligations of the registry operator under the terms and conditions of the base Registry Agreement or policies. This GDD General Operations Handbook should not serve as a substitute for the base Registry Agreement. As this document is meant to provide a high-level overview, you should not act or rely upon the information in this GDD General Operations Handbook without first confirming your obligations or rights under the base Registry Agreement itself. The information contained in this GDD General Operations Handbook shall not be deemed as legal advice by ICANN, and ICANN shall not be held liable for indirect, special, incidental, punitive or consequential damages of any kind including loss of profits, arising under or in connection with the registry operator's use of or reliance upon this GDD General Operations Handbook. -

Arnasgune Digitala Izatea Helburu: Puntueus Behatokia Ekimeneko Datuek Zer Gehiago Adierazten Duten

Arnasgune digitala izatea helburu: PuntuEUS Behatokia ekimeneko datuek zer gehiago adierazten duten Beñat Garaio Sarrera Erakunde eta gizarte zibilaren gidaritzapean, euskararen biziberritze prozesua indartzeko hamaika ekimen daude abian, denak halako denak izaera anitzekoak eta hainbat esparrutan euskarak dituen gabeziak estaltzeko asmoarekin sortutakoak.1 Azken urteotan berritzaileak izan dira, esaterako, lan-munduak euskararen erabilera sustatzeko eusle programa (Irureta Azkune, 2016), Eusko Jaurlaritzako Hizkuntza Politika Sailburuordetza euskararen bizitasun etnolinguistikoa aztertzeko jorratzen ari den Euskararen Adierazle Sistema (Eusko Jaurlaritza, d.g.) eta Kontseiluaren Hizkuntza Eskubideen Behatokiak euskaldunon hizkuntza eskubideen urraketak salatzeko sortutako Akuilari app erabilerraza (Behatokia, 2015). Testuinguru horretan, hau da, euskarak gero eta erabilera-esparru gehiago izateko mugimendu hori, hasi zen duela urte batzuk webguneetan .EUS2 domeinua lortzeko egitasmoa. Hain zuzen ere, 2007an sortu zen eragile batzuen baitan .EUS domeinua lortzeko nahia. Ondoren, 2008an PuntuEUS elkartea sortu zen «Euskararen eta Euskal Kulturaren Komunitatea egituratzeko helburuarekin». 2008tik 2012ra elkartea sostenguak biltzen aritu zen eta domeinuak banatzen dituen ICANN erakundeak elkarte horri domeinua berak kudeatu beharra zuela eskatu zionez, azken urte horretan sortu zen PuntuEUS Fundazioa. Handik gutxira, 2012ko ekainaren 14an onartu zuen ICANNek .EUS domeinua eta bi urte eskas behar izan ziren, Fundazioaren eta lehen aitzindarien -

Ebook-Secteur-Ndd.Pdf

Partenaires Projet porté par une équipe française, le Point BEST est l’une des nouvelles extensions les plus innovantes du secteur, avec notamment comme objectif une source d’avis informatifs sur tous types de produits et services à travers le monde. Service proposé par le courtier Philippe Franck, Domainium est la référence française pour l’achat de noms de domaine premium Service français lancé en 2019, DomExpire est un spécialiste de la récupération de noms de domaine expirés en .FR, connu pour sa transparence, son intégrité et son efficacité. EditeurWeb est un éditeur proposant des articles sponsorisés à haute valeur éditoriale (recherche d’angle, interviews, dossiers, etc.) sur plus de 1000 sites en propre et partenaires très thématisés Service français fondé en 2014, Kifdom est le leader de la récupération de nom de domaines expirés en .FR. L'entreprise qui gère Kifdom est également à la tête des services Ranxplorer et Ranks, ainsi que de l'outil Patate.fr NETIM est un bureau d'enregistrement français accrédité auprès de l'ICANN et proposant plus de 1000 extensions ainsi que des services d'hébergement, e-mails et certificats SSL. Des tarifs spécifiques pour revendeurs, des modules ainsi qu'une API sont également disponibles. Accrédité ICANN et doté de ses propres plateformes d'audit, de surveillance et d'optimisation, ainsi que d'équipes juridiques et sécurité DNS intégrées, SafeBrands adresse toutes les problématiques liées aux noms de domaine, qu'elles soient légales, marketing ou techniques. Surveillance de marque parmi les noms de domaine : détection phishing, contrefaçon, usurpation d'identité, détournement de trafic, atteinte à l'e- reputation Les avis émis dans le document n’engagent que son auteur, et non les organismes cités ci- après, que nous tenons à remercier pour l’aide apportée à la publication du présent document. -

Table of Contents – 26 November 2012.Docx

Separator Page Table of Contents – 26 November 2012.docx Page 1/44 Table of Contents – 26 November 2012 New gTLD Program Committee Workbook 1. Draft Resolutions 2. NGPC Submission 2012-11-26-01 - Prioritization Draw 3. Annex to NGPC Submission 2012-11-26 - Prioritization Draw 4. NGPC Submission 2012-11-26-02 - RCRC IOC Protection 5. NGPC Submission 2012-11-26-03 - IOG Names Protection Page 2/44 Separator Page 2012-11-26-DraftResolutions.docx Page 3/44 Draft Resolutions 26 November 2012 New gTLD Program Committee 1. Main Agenda: ...................................................................................................................... 2 a. RCRC IOC Protection ........................................................................................................ 2 Rationale for Resolution 2012.11.26.NGxx ........................................................................ 2 b. IGO Name Protection ....................................................................................................... 3 Rationale for Resolution 2012.11.26.NGxx ........................................................................ 4 Page 4/44 Draft Resolutions 26 November 2012 Page 2 of 6 1. Main Agenda: a. RCRC IOC Protection Whereas, the New gTLD Program Committee on 13 September 2012 requested that the GNSO Council advise the Board by no later than 31 January 2013 if it is aware of any reason, such as concerns with the global public interest or the security or stability of the DNS, that the Board should take into account in making its decision about whether to include second level protections for the IOC and Red Cross/Red Crescent names listed in section 2.2.1.2.3 of the Applicant Guidebook by inclusion on a Reserved Names List applicable in all new gTLD registries approved in the first round of the New gTLD Program. Whereas, the new gTLD Committee acknowledges that the GNSO Council has recently approved an expedited PDP to develop policy recommendations to protect the names and acronyms of IGOs and certain INGOs – including the RCRC and IOC, in all gTLDs. -

Territorialization of the Internet Domain Name System

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2018 Territorialization of the Internet Domain Name System Marketa Trimble University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Trimble, Marketa, "Territorialization of the Internet Domain Name System" (2018). Scholarly Works. 1020. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/1020 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Territorialization of the Internet Domain Name System Marketa Trimble* Abstract Territorializationof the internet-the linking of the internet to physical geography is a growing trend. Internet users have become accustomed to the conveniences of localized advertising, have enjoyed location-based services, and have witnessed an increasing use of geolocation and geo- blocking tools by service and content providers who for various reasons- either allow or block access to internet content based on users' physical locations. This article analyzes whether, and if so how, the trend toward territorializationhas affected the internetDomain Name System (DNS). As a hallmark of cyberspace governance that aimed to be detached from the territorially-partitionedgovernance of the physical world, the DNS might have been expected to resist territorialization-a design that seems antithetical to the original design of and intent for the internet as a globally distributed network that lacks a single point of control. -

Jakub Pawlak Wykorzystanie Nowych Domen Internetowych Najwyższego Rzędu Jako Narzędzia Promocji Mikro I Małego Przedsiębiorstwa

Jakub Pawlak Wykorzystanie nowych domen internetowych najwyższego rzędu jako narzędzia promocji mikro i małego przedsiębiorstwa Ekonomiczne Problemy Usług nr 111, 521-530 2014 ZESZYTY NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU SZCZECIŃSKIEGO NR 799 EKONOMICZNE PROBLEMY USŁUG NR 111 2014 JAKUB PAWLAK Politechnika Poznańska WYKORZYSTANIE NOWYCH DOMEN INTERNETOWYCH NAJWYŻSZEGO RZĘDU JAKO NARZĘDZIA PROMOCJI MIKRO I MAŁEGO PRZEDSIĘBIORSTWA Streszczenie Prezentacja internetowej witryny firmowej mikro i małego przedsiębiorstwa pod atrakcyjną, łatwą do zapamiętania domeną www, odzwierciedlającą charakter i branżę przedsiębiorstwa jest często zaniedbywaną metodą kształtowania promocji internetowej. 700 nowych domen najwyższego rzędu, które zostaną udostępnione do rejestracji w 2013 i 2015 roku, pozwoli rzeszy mikro i małych przedsiębiorstw wyróżnić swoją ofertę w internecie, podkreślając już w domenie pierwszego rzędu rodzaj działalności lub lokalizację przedsiębiorstwa. Zwłaszcza TLD geograficzne z nazwami miast i regionów ułatwi nie tylko wybór chwytliwego hasła w domenach drugiego poziomu, ale także wzmocni pozycję stron w wyszukiwarkach przy pozycjonowaniu witryn. Słowa kluczowe: marketing internetowy, domeny internetowe, IP Wprowadzenie Realia wskazują, iż 40% polskich przedsiębiorstw nie ma witryny internetowej1. Wedle badania agencji HBI Polska z 2011 roku, tylko 42% osób prowadzących jednoosobową działalność gospodarczą promowało się w taki sposób, w przeciwieństwie do aż 91% spółek akcyjnych dysponujących firmową stroną www2. Domeny internetowe, pod którymi -

Yokohama Domain Name Registration Policies

Domain Name Registration Policies (Version 1.1 June 10, 2014) Contents Contents................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Purpose and Principles of the .yokohama TLD ......................................................................................................................... 5 Launch Phases ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1. The Sunrise Phase and Trademark Claims Notice Services ........................................................................... 7 1.1. Purpose and Principles ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2. Sunrise Eligibility Requirements ........................................................................................................................................ 8 -

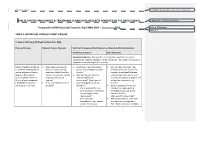

Data & Anecdotal Question

[Redline Copy] Formatted: Font:(Default) Calibri, (Asian) Calibri, Italic TABLES FOR THE RPM SUNRISE & TRADEMARK CLAIMS DATA REQUESTS APPROVED BY THE GNSO COUNCIL Comment [2]: _Accepted suggestion_ Prepared for RPM Data SuB Team Use By ICANN Staff – 19 January 2018 Deleted: 27 November Deleted: 7 TABLE 1: SURVEYS OF VARIOUS TARGET GROUPS 1. Survey of New gTLD Registry Operators (RO) Purpose & Scope Relevant Charter Question SuB Team’s Suggested Draft Questions, Notes & Additional Guidance Anecdotal Questions Data Questions Survey Introduction: This question is a subjective one that can only be answered by trademark holders. Some information that might contribute to a greater understanding of this question: Obtain anecdotal evidence ● Does Registry Sunrise or ● Did/do you view the Sunrise ● [can ask, but likely won’t get to facilitate Working Group Premium Name pricing period as providing a valuable answered] Did you receive any review of Sunrise Charter practices unfairly limit the service? complaints on behalf of brand Question #2 (whether ability of trademark owners ● Was Sunrise participation owners/registrants about your Sunrise and/or Premium to participate during something that you Sunrise pricing, including premium Pricing affects trademark Sunrise? encouraged? Was it part of pricing that applied during (TM) holders’ ability to ● If so, how extensive is this your strategy/how did you Sunrise? participate in Sunrise) problem? market it? ● Did you operate a formal (or o If yes, what practices or informal) premium pricing policies