Gechtoff PR.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helen Pashgianhelen Helen Pashgian L Acm a Delmonico • Prestel

HELEN HELEN PASHGIAN ELIEL HELEN PASHGIAN LACMA DELMONICO • PRESTEL HELEN CAROL S. ELIEL PASHGIAN 9 This exhibition was organized by the Published in conjunction with the exhibition Helen Pashgian: Light Invisible Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Funding at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California is provided by the Director’s Circle, with additional support from Suzanne Deal Booth (March 30–June 29, 2014). and David G. Booth. EXHIBITION ITINERARY Published by the Los Angeles County All rights reserved. No part of this book may Museum of Art be reproduced or transmitted in any form Los Angeles County Museum of Art 5905 Wilshire Boulevard or by any means, electronic or mechanical, March 30–June 29, 2014 Los Angeles, California 90036 including photocopy, recording, or any other (323) 857-6000 information storage and retrieval system, Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville www.lacma.org or otherwise without written permission from September 26, 2014–January 4, 2015 the publishers. Head of Publications: Lisa Gabrielle Mark Editor: Jennifer MacNair Stitt ISBN 978-3-7913-5385-2 Rights and Reproductions: Dawson Weber Creative Director: Lorraine Wild Designer: Xiaoqing Wang FRONT COVER, BACK COVER, Proofreader: Jane Hyun PAGES 3–6, 10, AND 11 Untitled, 2012–13, details and installation view Formed acrylic 1 Color Separator, Printer, and Binder: 12 parts, each approx. 96 17 ⁄2 20 inches PR1MARY COLOR In Helen Pashgian: Light Invisible, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2014 This book is typeset in Locator. PAGE 9 Helen Pashgian at work, Pasadena, 1970 Copyright ¦ 2014 Los Angeles County Museum of Art Printed and bound in Los Angeles, California Published in 2014 by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art In association with DelMonico Books • Prestel Prestel, a member of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Prestel Verlag Neumarkter Strasse 28 81673 Munich Germany Tel.: +49 (0)89 41 36 0 Fax: +49 (0)89 41 36 23 35 Prestel Publishing Ltd. -

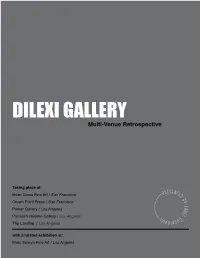

DILEXI GALLERY Multi-Venue Retrospective

DILEXI GALLERY Multi-Venue Retrospective Taking place at: Brian Gross Fine Art / San Francisco Crown Point Press / San Francisco Parker Gallery / Los Angeles Parrasch Heijnen Gallery / Los Angeles The Landing / Los Angeles with a related exhibition at: Marc Selwyn Fine Art / Los Angeles The Dilexi Multi-Venue Retrospective The Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco operated in the years and Southern Californian artists that had begun with his 1958-1969 and played a key role in the cultivation and friendship and tight relationship with well-known curator development of contemporary art in the Bay Area and Walter Hopps and the Ferus Gallery. beyond. The Dilexi’s young director Jim Newman had an implicit understanding of works that engaged paradigmatic Following the closure of its San Francisco venue, the Dilexi shifts, embraced new philosophical constructs, and served went on to become the Dilexi Foundation commissioning as vessels of sacred reverie for a new era. artist films, happenings, publications, and performances which sought to continue its objectives within a broader Dilexi presented artists who not only became some of the cultural sphere. most well-known in California and American art, but also notably distinguished itself by showcasing disparate artists This multi-venue exhibition, taking place in the summer of as a cohesive like-minded whole. It functioned much like 2019 at five galleries in both San Francisco and Los Angeles, a laboratory with variant chemical compounds that when rekindles the Dilexi’s original spirit of alliance. This staging combined offered a powerful philosophical formula that of multiple museum quality shows allows an exploration of actively transmuted the cultural landscape, allowing its the deeper philosophic underpinnings of the gallery’s role artists to find passage through the confining culture of the as a key vehicle in showcasing the breadth of ideas taking status quo toward a total liberation and mystical revolution. -

Venus Over Manhattan Is Pleased to Present an Exhibition of Work by Roy De Forest, Organized in Collaboration with the Roy De Forest Estate

Venus Over Manhattan is pleased to present an exhibition of work by Roy De Forest, organized in collaboration with the Roy De Forest Estate. Following the recent retrospective of his work, Of Dogs and Other People: The Art of Roy De Forest, organized by Susan Landauer at the Oakland Museum of California, the exhibition marks the largest presentation of De Forest’s work in New York since 1975, when the Whitney Museum of American Art staged a retrospective dedicated to his work. Comprising a large group of paintings, constructions, and works on paper—some of which have never before been exhibited—as well as a set of key loans from the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis, and the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art, Napa, the presentation surveys the breadth of De Forest’s production. In conjunction with the presentation, the gallery will publish a major catalogue featuring a new text on the artist by Dan Nadel, along with archival materials from the Roy De Forest papers, housed at the Archives of American Art. The exhibition will be on view from March 3rd through April 25th, 2020. Roy De Forest’s freewheeling vision, treasured for its combination of dots, dogs, and fantastical voyages, made him a pillar of Northern California’s artistic community for more than fifty years. Born in 1930 to migrant farmers in North Platte, Nebraska, De Forest and his family fled the dust bowl for Washington State, where he grew up on the family farm in the lush Yakima Valley, surrounded by dogs and farm animals. -

2015-011315Fed

National Register Nomination Case Report HEARING DATE: OCTOBER 21, 2015 Date: October 21, 2015 Case No.: 2015-011315FED Project Address: 800 Chestnut Street (San Francisco Art Institute) Zoning: RH-3 (Residential House, Three-Family) 40-X Height and Bulk District Block/Lot: 0049/001 Project Sponsor: Carol Roland-Nawi, Ph.D., State Historic Preservation Officer California Office of Historic Preservation 1725 23rd Street, Suite 100 Sacramento, CA 95816 Staff Contact: Shannon Ferguson – (415) 575-9074 [email protected] Reviewed By: Timothy Frye – (415) 575-6822 [email protected] Recommendation: Send resolution of findings recommending that, subject to revisions, OHP approve nomination of the subject property to the National Register BACKGROUND In its capacity as a Certified Local Government (CLG), the City and County of San Francisco is given the opportunity to comment on nominations to the National Register of Historic Places (National Register). Listing on the National Register of Historic Places provides recognition by the federal government of a building’s or district’s architectural and historical significance. The nomination materials for the individual listing of the San Francisco Art Institute at 800 Chestnut Street were prepared by Page & Turnbull. PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 800 Chestnut Street, also known as the San Francisco Art Institute, is located in San Francisco’s Russian Hill neighborhood on the northwest corner of Chestnut and Jones streets. The property comprises two buildings: the 1926 Spanish Colonial Revival style original building designed by Bakewell & Brown (original building) and the 1969 Brutalist addition designed by Paffard Keatinge-Clay (addition). Constructed of board formed concrete with red tile roofs, the original building is composed of small interconnected multi-level volumes that step up from Chestnut Street to Jones Street and range from one to two stories and features a five-story campanile, Churrigueresque entranceway and courtyard with tiled fountain. -

Inside and Around the 6 Gallery with Co-Founder Deborah Remington

Inside and Around the 6 Gallery with Co-Founder Deborah Remington Nancy M. Grace The College of Wooster As the site where Allen Ginsberg introduced “Howl” to the world on what the record most reliably says is Oct. 7, 1955, the 6 Gallery resonates for many as sacred ground, something akin to Henry David Thoreau’s gravesite in Concord, Massachusetts, or Edgar Allen Poe’s dorm room at the University of Virginia, or Willa Cather’s clapboard home in Red Cloud, Nebraska. Those who travel today to the site at 3119 Filmore in San Francisco find an upscale furniture boutique called Liv Furniture (Photos below courtesy of Tony Trigilio). Nonetheless, we imagine the 6 as it might have been, a vision derived primarily through our reading of The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac and “Poetry at The 6” by Michael McClure. Continuing the recovery work related to women associated with the Beat Generation that I began about ten years ago with Ronna Johnson of Tufts University, I’ve long 1 wanted to seek out a perspective on the 6 Gallery that has been not been integrated into our history of the institution: That of Deborah Remington, a co-founder – and the only woman co-founder—of the gallery. Her name appears in a cursory manner in descriptions of the 6, but little else to give her substance and significance. As sometimes happens, the path I took to find Remington was not conventional. In fact, she figuratively fell into my lap. Allison Schmidt, a professor of education at The College of Wooster where I teach, happens to be her cousin, something I didn’t know until Schmidt contacted me about two years ago and told me that Remington might be interested in talking with me as part of a family oral history project. -

A Finding Aid to the Sonia Gechtoff Papers, 1950-1980, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Sonia Gechtoff Papers, 1950-1980, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Josefson Processing of this collection received federal support from the Collections Care Initiative Fund, administered by the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative and the National Collections Program 2020/09/28 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series 1: Sonia Gechtoff papers, 1950-1980........................................................... 3 Sonia Gechtoff papers AAA.gechsoni Collection Overview Repository: Archives -

Paintings by Streeter Blair (January 12–February 7)

1960 Paintings by Streeter Blair (January 12–February 7) A publisher and an antique dealer for most of his life, Streeter Blair (1888–1966) began painting at the age of 61 in 1949. Blair became quite successful in a short amount of time with numerous exhibitions across the United States and Europe, including several one-man shows as early as 1951. He sought to recapture “those social and business customs which ended when motor cars became common in 1912, changing the life of America’s activities” in his artwork. He believed future generations should have a chance to visually examine a period in the United States before drastic technological change. This exhibition displayed twenty-one of his paintings and was well received by the public. Three of his paintings, the Eisenhower Farm loaned by Mr. & Mrs. George Walker, Bread Basket loaned by Mr. Peter Walker, and Highland Farm loaned by Miss Helen Moore, were sold during the exhibition. [Newsletter, memo, various letters] The Private World of Pablo Picasso (January 15–February 7) A notable exhibition of paintings, drawings, and graphics by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), accompanied by photographs of Picasso by Life photographer David Douglas Duncan (1916– 2018). Over thirty pieces were exhibited dating from 1900 to 1956 representing Picasso’s Lautrec, Cubist, Classic, and Guernica periods. These pieces supplemented the 181 Duncan photographs, shown through the arrangement of the American Federation of Art. The selected photographs were from the book of the same title by Duncan and were the first ever taken of Picasso in his home and studio. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ring around The Rose Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7426863k Author Ferrell, Elizabeth Allison Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ring around The Rose: Jay DeFeo and her Circle By Elizabeth Allison Ferrell A dissertation submitted for partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus Timothy Clark Professor Shannon Jackson Professor Darcy Grigsby Fall 2012 Copyright © Elizabeth Allison Ferrell 2012 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Ring around The Rose by Elizabeth Allison Ferrell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair From 1958 to 1966, the San Francisco artist Jay DeFeo (1929-89) worked on one artwork almost exclusively – a monumental oil-on-canvas painting titled The Rose. The painting’s protracted production isolated DeFeo from the mainstream art world and encouraged contemporaries to cast her as Romanticism’s lonely genius. However, during its creation, The Rose also served as an important matrix for collaboration among artists in DeFeo’s bohemian community. Her neighbors – such as Wallace Berman (1926-76) and Bruce Conner (1933-2008) – appropriated the painting in their works, blurring the boundaries of individual authorship and blending production and reception into a single process of exchange. I argue that these simultaneously creative and social interactions opened up the autonomous artwork, cloistered studio, and the concept of the individualistic artist championed in Cold-War America to negotiate more complex relationships between the individual and the collective. -

Spencer, Catherine. Coral and Lichen, Brains and Bowels- Jay

Coral and Lichen, Brains and Bowels: Jay DeFeo’s Hybrid Abstraction By Catherine Spencer 13 May 2015 Tate Papers no.23 Situating the US artist Jay DeFeo within a network of West Coast practitioners during the 1950s and 1960s, this essay shows how her relief paintings – layered with organic, geological and bodily referents – constitute what can be understood as ‘hybrid abstraction’. This has affinities with ‘eccentric abstraction’ and ‘funk art’, but also resonates with the socio-political context of Cold War America. Jay DeFeo has been repeatedly characterised by critics, historians and fellow artists as ‘an independent visionary’, devoted to ‘“private” art’, who was ‘professionally reclusive’.1 As early as 1963 the critic John Coplans cast DeFeo, together with other American artists working on the West Coast, including her friend Wallace Berman, as ‘isolated visionaries’ cloistered ‘in complete retreat’.2 The tenacity of this myth stems partly from the work for which DeFeo has become most famous, and indeed infamous: she re-worked her gargantuan oil painting The Rose obsessively between 1958 and 1966, and the energy expended on it forced a four-year career break until 1970.3 The Rose, and by extension DeFeo, have been co-opted as ‘representative of Bay Area abstract painting in microcosm’, invoked as symptomatic of West Coast 1950s and 1960s artistic production, understood as a brief flare of creativity eclipsed by New York.4 DeFeo’s hiatus seems to bisect her output into two sections: the works made during the 1950s and early 1960s on the one side, and those from the 1970s and the 1980s on the other.5 Yet rather than being an isolated or disjointed practice, DeFeo’s work exhibits remarkable consistency and, moreover, an ability to combine multiple influences and ideas. -

Landmark Exhibition at Denver Art Museum Highlights Women's Contributions to Abstract Expressionism

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACTS: Chelsea Beroza, 212-671-5160 [email protected] Barbara Escobar, 212-671-5174 [email protected] Images available upon request. Landmark Exhibition at Denver Art Museum Highlights Women’s Contributions to Abstract Expressionism Women of Abstract Expressionism expands understanding of seminal art movement with survey of more than 50 major works DENVER – April 28, 2016 –The Denver Art Museum (DAM) is proud to present the first full-scale museum presentation celebrating the female artists of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Organized by the DAM and curated by Gwen Chanzit, Women of Abstract Expressionism brings together 51 paintings to examine the distinct contributions of 12 artists who played an integral role in what has been recognized as the first fully-American modern art movement. On view June 12, 2016 through Sept. 25, 2016, the exhibition presents a nuanced profile of women working on the East and West Coasts during the 1940s and ’50s, providing scholars and audiences with a new perspective on this important chapter in art history. Following its debut at the DAM, Women of Abstract Expressionism will travel to the Mint Museum in October 2016 and to the Palm Springs Art Museum in February 2017. The DAM’s exhibition focuses on the expressive freedom of direct gesture and process at the core of abstract expressionism, while revealing inward reverie and painterly expression in these works by individuals responding to particular places, memories and life experiences. Women of Abstract Expressionism also sheds light on the unique experiences of artists based in the Bay Area on the West Lee Krasner, The Seasons, (1957). -

The San Francisco Bay Area 1945 – 1965

Subversive Art as Place, Identity and Bohemia: The San Francisco Bay Area 1945 – 1965 George Herms The Librarian, 1960. A text submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of The Glasgow School of Art For the degree of Master of Philosophy May 2015 © David Gracie 2015 i Abstract This thesis seeks evidence of time, place, and identity, as individualized artistic perspective impacting artists representing groups marginalized within dominant Western, specifically American culture, who lived in the San Francisco Bay Area between 1945–1965. Artists mirror the culture of the time in which they work. To examine this, I employ anthropological, sociological, ethnographic, and art historical pathways in my approach. Ethnic, racial, gender, class, sexual-orientation distinctions and inequities are examined via queer, and Marxist theory considerations, as well as a subjective/objective analysis of documented or existing artworks, philosophical, religious, and cultural theoretical concerns. I examine practice outputs by ethnic/immigrant, homosexual, and bohemian-positioned artists, exploring Saussurean interpretation of language or communicative roles in artwork and iconographic formation. I argue that varied and multiple Californian identities, as well as uniquely San Franciscan concerns, disseminated opposition to dominant United States cultural valuing and that these groups are often dismissed when produced by groups invisible within a dominant culture. I also argue that World War Two cultural upheaval induced Western societal reorganization enabling increased postmodern cultural inclusivity. Dominant societal repression resulted in ethnographic information being heavily coded by Bay Area artists when considering audiences. I examine alternative cultural support systems, art market accessibility, and attempt to decode product messages which reify enforced societal positioning. -

The Ring Around the Rose: Jay Defeo and Her Circle

The Ring around The Rose: Jay DeFeo and her Circle By Elizabeth Allison Ferrell A dissertation submitted for partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus Timothy Clark Professor Shannon Jackson Professor Darcy Grigsby Fall 2012 Copyright © Elizabeth Allison Ferrell 2012 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Ring around The Rose by Elizabeth Allison Ferrell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair From 1958 to 1966, the San Francisco artist Jay DeFeo (1929-89) worked on one artwork almost exclusively – a monumental oil-on-canvas painting titled The Rose. The painting’s protracted production isolated DeFeo from the mainstream art world and encouraged contemporaries to cast her as Romanticism’s lonely genius. However, during its creation, The Rose also served as an important matrix for collaboration among artists in DeFeo’s bohemian community. Her neighbors – such as Wallace Berman (1926-76) and Bruce Conner (1933-2008) – appropriated the painting in their works, blurring the boundaries of individual authorship and blending production and reception into a single process of exchange. I argue that these simultaneously creative and social interactions opened up the autonomous artwork, cloistered studio, and the concept of the individualistic artist championed in Cold-War America to negotiate more complex relationships between the individual and the collective. 1 To the memory of my best friend, Mila Noelle Rainof, M.D., whose compassion and courage will always inspire the best things I do i Table of Contents List of Figures………………………………………………………………………………….…iii Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………………....xi Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………….1 Chapter 1…………………………………………………………………………………………24 “S.F.