T H E J O U R N a L O F T H E F E L L & R O C K C L I M B I N G C L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NLCA06 Snowdonia - Page 1 of 12

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA06 Snowdonia Eryri – Disgrifiad cryno Dyma fro eang, wledig, uchel, sy’n cyd-ffinio’n fras â Pharc Cenedlaethol Eryri. Ei nodwedd bennaf yw ei mynyddoedd, o ba rai yr Wyddfa yw mynydd uchaf Cymru a Lloegr, yn 3560’ (1085m) o uchder. Mae’r mynyddoedd eraill yn cynnwys y Carneddau a’r Glyderau yn y gogledd, a’r Rhinogydd a Chadair Idris yn y de. Yma ceir llawer o fryndir mwyaf trawiadol y wlad, gan gynnwys pob un o gopaon Cymru sy’n uwch na 3,000 o droedfeddi. Mae llawer o nodweddion rhewlifol, gan gynnwys cribau llymion, cymoedd, clogwyni, llynnoedd (gan gynnwys Llyn Tegid, llyn mwyaf Cymru), corsydd, afonydd a rhaeadrau. Mae natur serth y tir yn gwneud teithio’n anodd, a chyfyngir mwyafrif y prif ffyrdd i waelodion dyffrynnoedd a thros fylchau uchel. Yn ddaearegol, mae’n ardal amrywiol, a fu â rhan bwysig yn natblygiad cynnar gwyddor daeareg. Denodd sylw rhai o sylfaenwyr yr wyddor, gan gynnwys Charles Darwin, a archwiliodd yr ardal ym 1831. Y mae ymhell, fodd bynnag, o fod yn ddim ond anialdir uchel. Am ganrifoedd, bu’r ardal yn arwydd ysbryd a rhyddid y wlad a’i phobl. Sefydlwyd bwrdeistrefi Dolgellau a’r Bala yng nghyfnod annibyniaeth Cymru cyn y goresgyniad Eingl-normanaidd. Felly, hefyd, llawer o aneddiadau llai ond hynafol fel Dinas Mawddwy. O’i ganolfan yn y Bala, dechreuodd y diwygiad Methodistaidd ar waith trawsffurfio Cymru a’r ffordd Gymreig o fyw yn y 18fed ganrif a’r 19eg. Y Gymraeg yw iaith mwyafrif y trigolion heddiw. -

Snowdon 500 – Route Descriptions

Snowdon 500 – Route Descriptions About Snowdon Snowdon is one of the most beautiful mountains in the world. Its grandeur impresses the visitor no matter which direction one looks at it. Its shape is like a starfish with six magnificent ridges radiating out, each with their own unique character and make up. The deep cwmoedd (glaciated valleys) dropping down from the ridges range from the easily accessible to those only reached by very experienced walkers and climbers. Snowdon, the highest mountain in England and Wales at 1085 m or 3560 ft, also offers a unique bio-diversity of rare flowers and insects, wonderful volcanic rock formations, fossils and disused mine works. For more information about the mountain and places to stay nearby visit www.snowdon.com Miners Track After registering and signing in at the start point in the car park in front of the Legacy – Royal Victoria Hotel you will be transported by our free shuttle bus to Pen Y Pass where you will receive your pre climb briefing before setting off for the summit of Mt Snowdon. The Miners Track to Llyn Glaslyn was built during the last century to serve the Britannia Copper Mines, abandoned in 1917. The Track is well defined and obvious until you reach Llyn Glaslyn but after that the path to the summit is considerably steeper and can be a serious undertaking especially in winter. The path starts at the far end of Pen Y Pass car park. At first the path contours gently with fine views down the Gwynant Valley on your left. -

Hill Walking & Mountaineering

Hill Walking & Mountaineering in Snowdonia Introduction The craggy heights of Snowdonia are justly regarded as the finest mountain range south of the Scottish Highlands. There is a different appeal to Snowdonia than, within the picturesque hills of, say, Cumbria, where cosy woodland seems to nestle in every valley and each hillside seems neatly manicured. Snowdonia’s hillsides are often rock strewn with deep rugged cwms biting into the flank of virtually every mountainside, sometimes converging from two directions to form soaring ridges which lead to lofty peaks. The proximity of the sea ensures that a fine day affords wonderful views, equally divided between the ever- changing seas and the serried ranks of mountains fading away into the distance. Eryri is the correct Welsh version of the area the English call Snowdonia; Yr Wyddfa is similarly the correct name for the summit of Snowdon, although Snowdon is often used to demarcate the whole massif around the summit. The mountains of Snowdonia stretch nearly fifty miles from the northern heights of the Carneddau, looming darkly over Conwy Bay, to the southern fringes of the Cadair Idris massif, overlooking the tranquil estuary of the Afon Dyfi and Cardigan Bay. From the western end of the Nantlle Ridge to the eastern borders of the Aran range is around twenty- five miles. Within this area lie nine distinct mountain groups containing a wealth of mountain walking possibilities, while just outside the National Park, the Rivals sit astride the Lleyn Peninsula and the Berwyns roll upwards to the east of Bala. The traditional bases of Llanberis, Bethesda, Capel Curig, Betws y Coed and Beddgelert serve the northern hills and in the south Barmouth, Dinas Mawddwy, Dolgellau, Tywyn, Machynlleth and Bala provide good locations for accessing the mountains. -

Eryrinewsspring-Summer2021 (Pdf)

Spring/ Summer Newsletter – May 2021 Editorial – Jane Berry What a pleasure that we can now walk in groups again, I have enjoyed two so far with fine weather for both. Thank you to all those who have contributed to this Newsletter, as always articles and photographs are very welcome. The next issue will be sent out in early August. Chairman – Dafydd Jones First of all can I offer our thanks to Roy and Jo-Anne, for keeping us all going with their positive messages about reopening our programme of walks. Roy has also gone a long way to convincing others to use the system he has created as our scheduling and booking system for our programme of walks or develop a better one. Many thanks to you both. I also want to thank those of you that have already put your hands up to lead walks as we come out of this lockdown, also the keen walkers that have already booked many of the walks. You already know that we haven't had a committee meeting for months, something I shall try to correct in the coming weeks. On a personal note apologies to all of you that were contacted by the hackers that got into my email account,hope you didn’t suffer. The saga is not over at my end but I hope to have some semblance of order in the next week with a "new" account etc. As for Covid , hope you have all stayed well and healthy and will get back to leading and joining walks as soon as you feel able to. -

5-Night Southern Snowdonia Big Mountain Walks

5-Night Southern Snowdonia Big Mountain Walks Tour Style: Challenge Walks Destinations: Snowdonia & Wales Trip code: DGBGW-5 Trip Walking Grade: 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Complete some of Snowdonia’s finest mountain ridges on this exciting holiday. These routes often include a bit of scrambling to add interest and finish on a pointy summit, so you know you’ve "topped out". The “Big Mountain Walks” holidays feature some absolute classics, all of which are must-do's for keen hillwalkers. And if you've done them before you know you'll never tire of this fine collection. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 4 days guided walking • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Discover the dramatic scenery and history of Southern Snowdonia • Tackle some of Wale's finest ridge walks • Discover the wild and rugged Rhinogs • Ascend Cadair Idris via the famous Minffordd Path • Tackle some of Snowdonia’s finest ridges • Enjoy the rocky Aran ridge and visit the highest point in Southern Snowdonia TRIP SUITABILITY Big Walks Snowdonia - The nature of these routes means that the days will be long and strenuous with considerable steep ascents and descents over rough ground, bogs and streams, and will include easy scrambling up to Grade 1. The routes also involve moving along narrow airy ridges and walking above steep slopes where a slip could have serious consequences. -

ECN Annual Report

Environmental Change Network Yr Wyddfa/Snowdon site Summary of measurements and trends over the period 1995-2015 Alex Turner and Victoria Bowmaker NRW Evidence Report No 166 This report is dedicated to Jonathan Yeardley, one of our best volunteers, who sadly lost his life in a car accident in May 2016. The report should be cited as: Turner, A.J. & Bowmaker, V. (2016) NRW Evidence Report No 166. Environmental Change Network Yr Wyddfa/Snowdon site Summary of measurements and trends over the period 1995-2015. Natural Resources Wales, Bangor. Alex Turner, July 2016 Page 2 of 125 www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk Contents Crynodeb Gweithredol 4 Executive Summary 7 1. Introduction 10 2. Site protocols 2.1 Summary of measurements undertaken on Snowdon 13 3. Terrestrial and Freshwater measurements and trends 3.1 Summary of trends for physical variables 17 3.2 Summary of trends for chemical variables 40 3.3 Summary of trends for biological variables 65 3.4 Summary of trends for land use and cultural services 99 4. Abbreviations 106 5. References 106 Appendix 1 Trend statistics 109 Alex Turner, July 2016 Page 3 of 125 www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk Crynodeb Gweithredol Mae safle’r Rhwydwaith Newid Amgylcheddol ar Yr Wyddfa yn rhan o rwydwaith monitro 11 safle daearol a 42 safle dŵr croyw. Ymgymerir â gweithredoedd ar y safle gan Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru (CNC) (a gan Gyngor Cefn Gwlad Cymru yn flaenorol) gyda chefnogaeth Llywodraeth Cymru. Mae’r monitro yn canolbwyntio ar effaith newid hinsawdd, llygredd a defnyddio tir ar strwythur, gweithrediad ac amrywiaeth ecosystemau daearol a dŵr croyw. -

The Pinnacle Club Journal 1950 '—

THE © PinnaclePINNACLE Club and Author All Rights Reserved CLUB JOURNAL I95O Edited by HELEN BRYAN CONTENTS Page Foreword E. Wells .. 7 Eighteen Days in the Western Himalayas.. Gladys Jean Low (Mrs. Ptame/t) 9 Alpine Meet, 1949 E. Worsley Leech 21 Reminiscences of the Canadian Rockies .. M.I.Jeffrey .. 26 Bosigran Nea Morin 33 Munro-ing A. Hirst Laliderer Spitze, Nordkanta E. Longstaff Two Visits to Arran E. Wells .. 51 Impressions of the French Alps Given Moffat Three Days in Buttermerc C. L. Corbett Return to the Alps Freda Rylatt 70 Snowdonia My Measuring Stick E. Worsley Leech 74 Alpine Scotland E. M. Gregory 78 Autumn Days in Derbyshire Nancy Carpenter 82 Idle Thoughts of an Idle Climber Phy His Raven 86 Excursion into Ethnology H. C. Bryan 91 Club Notes A. Wilson 94 Obituary ; Reviews ; Editor's Note 95 to 102 Copies may be obtained from : Hon. Editor: Mrs. H. C BRYAN, Rosebank, Blakemere, Hereford. Hon. Secretary: Miss M. WOOD, i Grove Avenue, Frizinghall, Bradford. PUBLISHED BY THE PINNACLE CLUB © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL 1950 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved ' —. r: H a © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved The Pinnacle Club Journal 1950 EDITED BY HELEN BRYAN STOCKPORT THE CLOISTER PRESS LIMITED © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved r.vn.vx LOWF. (\[RS. WORSI.FY LEFCH) PRESIDENT 1946-^9 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB 1950 OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE : President : Miss E. WELLS Westmead, Moorland View, Ben Rhydding, Yorks. Vice-President: Mrs. E. -

The Welsh 3000S Trip Code: WTT

The Welsh 3000s Trip code: WTT Overview Total 1 day n/a Difficulty: Hiking 1 day Wales, UK All year round “More Adventure were amazing. The hike was very well organised and our guides made the challenge fun. I will definitely be doing more challenges with these guys!” Paul, 2018 Tackle all fifteen peaks in Wales above 3000 feet in under 24 hours - this is the Welsh 3000s, one of the most iconic challenges in the UK. This incredible 42km adventure is an unforgettable journey on two feet through the wild landscape of Snowdonia National Park. The official challenge is completed in under 24 hours, but we think completing it in any time should be on everyone’s bucket list! It is a fully guided and supported event, allowing you to focus on the epic scenery of this unique region of the UK. Highlights ● The breathtaking mountain scenery of Snowdonia National Park ● Embracing the physical challenge of tackling fifteen mountains ● Experiencing the awe-inspiring wilderness and beauty of North Wales ● Sharing the adventure of a lifetime with your other team members ● Completing a unique iconic mountain challenge ● Encountering the wild ponies of the Carneddau, our favourite mountain residents Itinerary Our route begins from the popular Pen y Pas car park at the top of the Llanberis Pass. Here you’ll meet the rest of the group and your leaders. There are toilets available and you’ll also be able to place a bag with extra snacks, clothing and drinks in our support vehicle for our planned refreshment stop. After a safety brief, overview of the day and kit check, we’ll begin by following the Pyg track then embark upon arguably the most technically demanding section of the challenge, the narrow edge of Crib Goch. -

Rock Trails Snowdonia

CHAPTER 6 Snowdon’s Ice Age The period between the end of the Caledonian mountain-building episode, about 400 million years ago, and the start of the Ice Ages, in much more recent times, has left little record in central Snowdonia of what happened during those intervening aeons. For some of that time central Snowdonia was above sea level. During those periods a lot of material would have been eroded away, millimetre by millimetre, year by year, for millions of years, reducing the Alpine or Himalayan-sized mountains of the Caledonides range to a few hardened stumps, the mountains we see today. There were further tectonic events elsewhere on the earth which affected Snowdonia, such as the collision of Africa and Europe, but with much less far-reaching consequences. We can assume that central Snowdonia was also almost certainly under sea level at other times. During these periods new sedimentary rocks would have been laid down. However, if this did happen, there is no evidence to show it that it did and any rocks that were laid down have been entirely eroded away. For example, many geologists believe that the whole of Britain must have been below sea level during the era known as the ‘Cretaceous’ (from 145 million until 60 million years ago). This was the period during which the chalk for- mations were laid down and which today crop out in much of southern and eastern Britain. The present theory assumes that chalk was laid down over the whole of Britain and that it has been entirely eroded away from all those areas where older rocks are exposed, including central Snowdonia. -

Yr Wyddfa I Foel Fras Mewn Diwrnod

Yr Wyddfa i Foel Fras mewn diwrnod Challenges can be considered a bit naff, and I’d agree being in the hills isn’t just about proving or conquering. But sometimes the thought of doing something just gets in your head and gnaws away. Shane and I had our first go at the Welsh 3000s last year and after all it is a magnificent line. You simply start at one end and string together all the 3000ft tops until you’ve got to the top of all 14 (or is it 15), following a meandering but satisfying succession of ridges and whaleback plateaus. Everyone knows the Snowdon horseshoe, the round of the Glyders and the Carneddau, each a straight forward day walk so linking them appeals just as a logical thing to do. Our first attempt got us to Ogwyn. That was the point when we both realised that perhaps it wasn’t that easy. Forty kilometers is fair enough, but actually you need to go up and down 4000m and then also add on a couple of 6k walks at the start and end. What Finlay Wild does in 4 hours translates into considerably more of a challenge for most middle aged punters. The frustrating thing was that after the first go at we both knew we had got pretty close. Although in terms of distance Ogwyn is only half way, you realise that once at the top of Pen Y Ole Wen the major difficulties are over. And that’s why it was gnawing away, we were keen to try again. -

The Far Side of the Sky

The Far Side of the Sky Christopher E. Brennen Pasadena, California Dankat Publishing Company Copyright c 2014 Christopher E. Brennen All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from Christopher Earls Brennen. ISBN-0-9667409-1-2 Preface In this collection of stories, I have recorded some of my adventures on the mountains of the world. I make no pretense to being anything other than an average hiker for, as the first stories tell, I came to enjoy the mountains quite late in life. But, like thousands before me, I was drawn increasingly toward the wilderness, partly because of the physical challenge at a time when all I had left was a native courage (some might say foolhardiness), and partly because of a desire to find the limits of my own frailty. As these stories tell, I think I found several such limits; there are some I am proud of and some I am not. Of course, there was also the grandeur and magnificence of the mountains. There is nothing quite to compare with the feeling that envelopes you when, after toiling for many hours looking at rock and dirt a few feet away, the world suddenly opens up and one can see for hundreds of miles in all directions. If I were a religious man, I would feel spirits in the wind, the waterfalls, the trees and the rock. Many of these adventures would not have been possible without the mar- velous companionship that I enjoyed along the way. -

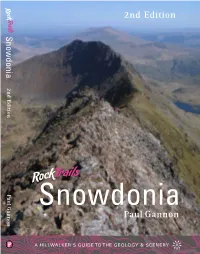

Paul Gannon 2Nd Edition

2nd Edition In the first half of the book Paul discusses the mountain formation Paul Gannon is a science and of central Snowdonia. The second half of the book details technology writer. He is author Snowdonia seventeen walks, some easy, some more challenging, which bear Snowdonia of the Rock Trails series and other books including the widely evidence of the story told so far. A HILLWalker’s guide TO THE GEOLOGY & SCENERY praised account of the birth of the Walk #1 Snowdon The origins of the magnificent scenery of Snowdonia explained, and a guide to some electronic computer during the Walk #2 Glyder Fawr & Twll Du great walks which reveal the grand story of the creation of such a landscape. Second World War, Colossus: Bletchley Park’s Greatest Secret. Walk #3 Glyder Fach Continental plates collide; volcanoes burst through the earth’s crust; great flows of ash He also organises walks for hillwalkers interested in finding out Walk #4 Tryfan and molten rock pour into the sea; rock is strained to the point of catastrophic collapse; 2nd Edition more about the geology and scenery of upland areas. Walk #5 Y Carneddau and ancient glaciers scour the land. Left behind are clues to these awesome events, the (www.landscape-walks.co.uk) Walk #6 Elidir Fawr small details will not escape you, all around are signs, underfoot and up close. Press comments about this series: Rock Trails Snowdonia Walk #7 Carnedd y Cribau 1 Paul leads you on a series of seventeen walks on and around Snowdon, including the Snowdon LLYN CWMFFYNNON “… you’ll be surprised at how much you’ve missed over the years.” Start / Finish Walk #8 Northern Glyderau Cwms A FON NANT PERIS A4086 Carneddau, the Glyders and Tryfan, Nant Gwynant, Llanberis Pass and Cadair Idris.