IIS Windows Server

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Composing Pioneers: Personal Writing and the Making of Frontier Opportunity in Nineteenth- Century America Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/56b1f2zv Author Wagner, William E. Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Composing Pioneers: Personal Writing and the Making of Frontier Opportunity in Nineteenth-Century America by William Edward Wagner A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor David M. Henkin, Chair Professor Waldo E. Martin Jr. Professor Samuel Otter Fall 2011 Composing Pioneers: Personal Writing and the Making of Frontier Opportunity in Nineteenth-Century America Copyright 2011 by William Edward Wagner Abstract Composing Pioneers: Personal Writing and the Making of Frontier Opportunity in Nineteenth-Century America by William Edward Wagner Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor David M. Henkin, Chair Few slogans occupy a more prominent place in popular mythology about the frontier than the exhortation, “Go west, young man, and grow up with the country.” Despite its enduring popularity, surprisingly little scholarly attention has been devoted to probing the constellation of ideas about movement, place, masculinity, and social mobility that is captured in this short phrase. This dissertation explores how, in the decades between the War of 1812 and the Civil War, Americans began to think and write about the possibilities for “growing up” with new cities, towns, and agricultural communities on the frontier. -

A History of the California Supreme Court in Its First Three Decades, 1850–1879

BOOK SECTION A HISTORY OF THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT IN ITS FIRST THREE DECADES, 1850–1879 293 A HISTORY OF THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT IN ITS FIRST THREE DECADES, 1850–1879 ARNOLD ROTH* PREFACE he history of the United States has been written not merely in the “T halls of Congress, in the Executive offices, and on the battlefields, but to a great extent in the chambers of the Supreme Court of the United States.”1 It is no exaggeration to say that the Supreme Court of California holds an analogous position in the history of the Golden State. The discovery of gold made California a turbulent and volatile state during the first decades of statehood. The presence of the precious ore transformed an essentially pastoral society into an active commercial and industrial society. Drawn to what was once a relatively tranquil Mexican province was a disparate population from all sections of the United States and from many foreign nations. Helping to create order from veritable chaos was the California Supreme Court. The Court served the dual function of bringing a settled * Ph.D., University of Southern California, 1973 (see Preface for additional information). 1 Charles Warren, The Supreme Court in United States History, vol. I (2 vols.; rev. ed., Boston; Little, Brown, and Company, 1922, 1926), 1. 294 CALIFORNIA LEGAL HISTORY ✯ VOLUME 14, 2019 order of affairs to the state, and also, in a less noticeable role, of providing a sense of continuity with the rest of the nation by bringing the state into the mainstream of American law. -

Parish of Skipton*

294 HISTORY OF CRAVEN. PARISH OF SKIPTON* HAVE reserved for this parish, the most interesting part of my subject, a place in Wharfdale, in order to deduce the honour and fee of Skipton from Bolton, to which it originally belonged. In the later Saxon times Bodeltone, or Botltunef (the town of the principal mansion), was the property of Earl Edwin, whose large possessions in the North were among the last estates in the kingdom which, after the Conquest, were permitted to remain in the hands of their former owners. This nobleman was son of Leofwine, and brother of Leofric, Earls of Mercia.J It is somewhat remarkable that after the forfeiture the posterity of this family, in the second generation, became possessed of these estates again by the marriage of William de Meschines with Cecilia de Romille. This will be proved by the following table:— •——————————;——————————iLeofwine Earl of Mercia§=j=......... Leofric §=Godiva Norman. Edwin, the Edwinus Comes of Ermenilda=Ricardus de Abrineis cognom. Domesday. Goz. I———— Matilda=.. —————— I Ranulph de Meschines, Earl of Chester, William de Meschines=Cecilia, daughter and heir of Robert Romille, ob. 1129. Lord of Skipton. But it was before the Domesday Survey that this nobleman had incurred the forfeiture; and his lands in Craven are accordingly surveyed under the head of TERRA REGIS. All these, consisting of LXXVII carucates, lay waste, having never recovered from the Danish ravages. Of these-— [* The parish is situated partly in the wapontake of Staincliffe and partly in Claro, and comprises the townships of Skipton, Barden, Beamsley, Bolton Abbey, Draughton, Embsay-with-Eastby, Haltoneast-with-Bolton, and Hazlewood- with-Storithes ; and contains an area of 24,7893. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

13.09.2018 Orcid # 0000-0002-3893-543X

JAST, 2018; 49: 59-76 Submitted: 11.07.2018 Accepted: 13.09.2018 ORCID # 0000-0002-3893-543X Dystopian Misogyny: Returning to 1970s Feminist Theory through Kelly Sue DeConnick’s Bitch Planet Kaan Gazne Abstract Although the Civil Rights Movement led the way for African American equality during the 1960s, activist women struggled to find a permanent place in the movement since key leaders, such as Stokely Carmichael, were openly discriminating against them and marginalizing their concerns. Women of color, radical women, working class women, and lesbians were ignored, and looked to “women’s liberation,” a branch of feminism which focused on consciousness- raising and social action, for answers. Women’s liberationists were also committed to theory making, and expressed their radical social and political ideas through countless essays and manifestos, such as Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto (1967), Jo Freeman’s BITCH Manifesto (1968), the Redstockings Manifesto (1969), and the Radicalesbians’ The Woman-Identified Woman (1970). Kelly Sue DeConnick’s American comic book series Bitch Planet (2014–present) is a modern adaptation of the issues expressed in these radical second wave feminist manifestos. Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future ruled by men where disobedient women—those who refuse to conform to traditional female gender roles, such as being subordinate, attractive (thin), and obedient “housewives”—are exiled to a different planet, Bitch Planet, as punishment. Although Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future, as this article will argue, it uses the theoretical framework of radical second wave feminists to explore the problems of contemporary American women. 59 Kaan Gazne Keywords Comic books, Misogyny, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Dystopia Distopik Cinsiyetçilik: Kelly Sue DeConnick’in Bitch Planet Eseri ile 1970’lerin Feminist Kuramına Geri Dönüş Öz Sivil Haklar Hareketi Afrikalı Amerikalıların eşitliği yolunda önemli bir rol üstlenmesine rağmen, birçok aktivist kadın kendilerine bu hareketin içinde bir yer edinmekte zorlandılar. -

Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books

The Visualization of the Twisted Tongue: Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books JEFFREY K. JOHNSON HERE IS A WELL-ESTABLISHED TRADITION WITHIN THE ENTERTAINMENT and publishing industries of depicting mentally and physically challenged characters. While many of the early renderings were sideshowesque amusements or one-dimensional melodramas, numerous contemporary works have utilized characters with disabilities in well- rounded and nonstereotypical ways. Although it would appear that many in society have begun to demand more realistic portrayals of characters with physical and mental challenges, one impediment that is still often typified by coarse caricatures is that of stuttering. The speech impediment labeled stuttering is often used as a crude formulaic storytelling device that adheres to basic misconceptions about the condition. Stuttering is frequently used as visual shorthand to communicate humor, nervousness, weakness, or unheroic/villainous characters. Because almost all the monographs written about the por- trayals of disabilities in film and television fail to mention stuttering, the purpose of this article is to examine the basic categorical formulas used in depicting stuttering in the mainstream popular culture areas of film, television, and comic books.' Though the subject may seem minor or unimportant, it does in fact provide an outlet to observe the relationship between a physical condition and the popular conception of the mental and personality traits that accompany it. One widely accepted definition of stuttering is, "the interruption of the flow of speech by hesitations, prolongation of sounds and blockages sufficient to cause anxiety and impair verbal communication" (Carlisle 4). The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 41, No. -

The EERI Oral History Series

CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace Stanley Scott, Interviewer Earthquake Engineering Research Institute Editor: Gail Hynes Shea, Albany, CA ([email protected]) Cover and book design: Laura H. Moger, Moorpark, CA Copyright ©1999 by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part may be reproduced, quoted, or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the executive director of the Earthquake Engi- neering Research Institute or the Director of the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the oral history subject and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute or the University of California. Published by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute 499 14th Street, Suite 320 Oakland, CA 94612-1934 Tel: (510) 451-0905 Fax: (510) 451-5411 E-Mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.eeri.org EERI Publication No.: OHS-6 ISBN 0-943198-99-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wallace, R. E. (Robert Earl), 1916- Robert E. Wallace / Stanley Scott, interviewer. p. cm – (Connections: the EERI oral history series ; 7) (EERI publication ; no. -

People V. Hall, Which Reversed the Murder Conviction of George W

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2017 In 1854, the Supreme Court of California decided the infamous case of People v. Hall, which reversed the murder conviction of George W. Hall, “a free white citizen of this State,” because three prosecution witnesses were Chinese. One legal scholar called the decision “the worst statutory interpretation case in history.” Another described it as “containing some of the most offensive racial rhetoric to be found in the annals of California appellate jurisprudence.” Read about People V. Hall in Michael Traynor’s article Starting on page 2 The Infamous Case of People v. Hall (1854) An Odious Symbol of Its Time By Michael Traynor* Chinese Camp in the Mines, [P. 265 Illus., from Three Years in California, by J.D. Borthwick] Courtesy, California Historical Society, CHS2010.431 n 1854, the Supreme Court of California decided the form of law.”5 According to Professor John Nagle, it the case of People v. Hall, which reversed the murder is “the worst statutory interpretation case in history.”6 It Iconviction of George W. Hall, “a free white citizen of preceded in infamy the Dred Scott case three years later.7 this State,” because three prosecution witnesses were Chi- Instead of a legal critique, this note provides brief nese.1 The court held their testimony inadmissible under context from a period of rising hostility to Chinese an 1850 statute providing that “[n]o black or mulatto per- immigrants in California. It aims to help us compre- son, or Indian, shall be permitted to give evidence in favor hend the odious decision while not excusing it.8 of, or against, a white person.”2 Here are just a few highlights from eventful 1854, If cases could be removed from the books, People starting nationally and then going to California and v. -

Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris Triseriata), Great Lakes/ St

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata), Great Lakes/ St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population, in Canada Western Chorus Frog 2014 1 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2014. Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata), Great Lakes / St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population, in Canada [Proposed], Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series, Environment Canada, Ottawa, v + 46 pp For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca). Cover illustration: © Raymond Belhumeur Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de la rainette faux-grillon de l’Ouest (Pseudacris triseriata), population des Grands Lacs et Saint-Laurent et du Bouclier canadien, au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog 2014 (Great Lakes / St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population) PREFACE The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years of the publication of the final document on the Species at Risk Public Registry. -

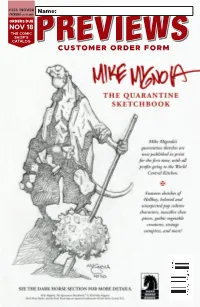

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

Emanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church New London, Wisconsin

Emanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church New London, Wisconsin Celebrating 125 years of God’s Grace September 10, 1893 – September 10, 2018 We Rejoice with Thanksgiving – Psalm 95:1-2 Come, let us sign for joy to the Lord; let us shout aloud to the Rock of our salvation. Let us come before him with thanksgiving and extol him with music and song Anniversary Committee Pastor William Heiges – Advisor Dale Krause – Chairman Sue Besaw Jean Gorman Marsha Krause Edward Krause Sandra Krause Mary Schoenrock Julie Schoenrock Cyndy Schulz Shirley Steingraber Janet Strebe A special note of thanks goes to the following: Pastor William Heiges – Advisor to the committee Pastor Mark Tiefel who designed the nine worship services Mr. Ed Krause who researched and wrote the history on the following pages Mr. Dale Krause for the research on the pastors who served Emanuel and the sons and daughters of Emanuel who entered the public ministry Ms. Susan Willems, WELS Archivist, for her research assistance Mr. Stephen Balza, Martin Luther College, Director of Alumni Relations, for his research assistance Mr. & Mrs. Greg Mathewson, Mathewson Monuments, for support with the anniversary dinner The information contained in this booklet is thought to be correct. If there are omissions or needed corrections, please accept our apologies. It was not intentional. 1 Historical Setting In the years before 1850 a considerable number of Native Americans lived in the region of the confluence of the Wolf and Embarrass rivers. The rivers were the highways which made travel easy. This area had a rich soil to grow crops; was full of wild game and fish which made the area attractive for the Native Americans. -

Rwitc, Ltd. Annual Auction Sale of Two Year Old Bloodstock 142 Lots

2020 R.W.I.T.C., LTD. ANNUAL AUCTION SALE OF TWO YEAR OLD BLOODSTOCK 142 LOTS ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. Mahalakshmi Race Course 6 Arjun Marg MUMBAI - 400 034 PUNE - 411 001 2020 TWO YEAR OLDS TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION BY ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. IN THE Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034 ON MONDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 03RD (LOT NUMBERS 1 TO 71) AND TUESDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 04TH (LOT NUMBERS 72 TO 142) Published by: N.H.S. Mani Secretary & CEO, Royal Western India Turf Club, Ltd. eistere ce Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034. Printed at: MUDRA 383, Narayan Peth, Pune - 411 030. IMPORTANT NOTICES ALLOTMENT OF RACING STABLES Acceptance of an entry for the Sale does not automatically entitle the Vendor/Owner of a 2-Year-Old for racing stable accommodation in Western India. Racing stable accommodation in Western India will be allotted as per the norms being formulated by the Stewards of the Club and will be at their sole discretion. THIS CLAUSE OVERRIDES ANY OTHER RELEVANT CLAUSE. For application of Ownership under the Royal Western India Turf Club Limited, Rules of Racing. For further details please contact Stipendiary Steward at [email protected] BUYERS BEWARE All prospective buyers, who intend purchasing any of the lots rolling, are requested to kindly note:- 1. All Sale Forms are to be lodged with a Turf Authority only since all foals born in 2018 are under jurisdiction of Turf Authorities with effect from Jan .