The Atlantic Coast Conference: a Pre- and Post-Expansion Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic Coast Conference

ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER 2011 Atlantic Coast Conference Early Season Football Television Schedule Release (All times Eastern) Date ............. Game ...................................................... .................. Network ................................ Gametime Sept. 1 ........... Western Carolina at Georgia Tech ... ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 7:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Northwestern at Boston College ....... ..................... ESPNU .......................................... Noon Sept. 3 ........... Appalachian State at Virginia Tech .. ..................... ACC Network ............................... 12:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Troy at Clemson ........................................ ..................... ESPN3.com ................................... 3:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Louisiana Monroe at Florida State ... ..................... ESPNU ........................................... 3:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... James Madison at North Carolina ..... ..................... RSN ..... ........................................... 3:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Liberty at NC State ................................... ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 6 pm Sept. 3 ........... William & Mary at Virginia .................. ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 6 pm Sept. 3 ........... Richmond at Duke ................................... ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 7 pm -

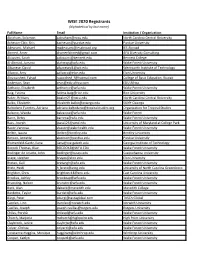

WISE 2020 Registrants

WISE 2020 Registrants (alphabetical by last name) Full Name Email Institution / Organization Abraham, Solomon [email protected] North Carolina Central University Acheson-Clair, Kris [email protected] Purdue University Adewumi, Michael [email protected] IES Abroad Ahmed, Amer [email protected] AFA Diversity Consulting Akiwumi, Sarah [email protected] Bennett College Al-Ahmad, Jumana [email protected] Wake Forest University Albanese, David [email protected] Wentworth Institute of Technology Allocco, Amy [email protected] Elon University Alruwaished, Fahad [email protected] College of Basic Education, Kuwait Anderson, Sean [email protected] EDU Africa Anthony, Elizabeth [email protected] Wake Forest University Baig, Fatima [email protected] Rice University Baker, Brittany [email protected] North Carolina Central University Balko, Elizabeth [email protected] SUNY-Oswego Baltodano Fuentes, Adriana [email protected] Organization for Tropical Studies Balzano, Wanda [email protected] Wake Forest Barre, Betsy [email protected] Wake Forest University Bass, Joseph [email protected] University of Maryland at College Park Baute,Vanessa [email protected] Wake Forest University Beltre, Isaura [email protected] Bentley University Benson, Annette [email protected] Purdue University Blumenfeld-Gantz, Ilana [email protected] Georgia Institute of Technology Bocook Thomas, Blair [email protected] Wake Forest University Bodinger de Uriarte, John [email protected] Susquehanna University braye, stephen -

Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963

SUTTELL, BRIAN WILLIAM, Ph.D. Campus to Counter: Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963. (2017) Directed by Dr. Charles C. Bolton. 296 pp. This work investigates civil rights activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, in the early 1960s, especially among students at Shaw University, Saint Augustine’s College (Saint Augustine’s University today), and North Carolina College at Durham (North Carolina Central University today). Their significance in challenging traditional practices in regard to race relations has been underrepresented in the historiography of the civil rights movement. Students from these three historically black schools played a crucial role in bringing about the end of segregation in public accommodations and the reduction of discriminatory hiring practices. While student activists often proceeded from campus to the lunch counters to participate in sit-in demonstrations, their actions also represented a counter to businesspersons and politicians who sought to preserve a segregationist view of Tar Heel hospitality. The research presented in this dissertation demonstrates the ways in which ideas of academic freedom gave additional ideological force to the civil rights movement and helped garner support from students and faculty from the “Research Triangle” schools comprised of North Carolina State College (North Carolina State University today), Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Many students from both the “Protest Triangle” (my term for the activists at the three historically black schools) and “Research Triangle” schools viewed efforts by local and state politicians to thwart student participation in sit-ins and other forms of protest as a restriction of their academic freedom. -

Wake Forest University Fact Book 2013-2014 Twenty-Third Edition

2013‐2014 Fact Book Office of Institutional Research Wake Forest University Fact Book 2013-2014 Twenty-third Edition – April 2014 Reynolda Campus Wake Forest College, School of Business, School of Law, Graduate School, and Divinity School Bowman Gray Campus Wake Forest University School of Medicine (includes Physician Assistant Program) and Graduate School Office of Institutional Research Phil Handwerk, Director Adam Shick, Associate Director Sara Gravitt, Assistant Director Justin DeBenedetto, Graduate Assistant P. O. Box 7373 Reynolda Station, Winston-Salem, NC 27109 (336) 758-5244 Web site: http://www.wfu.edu/ir Table of Contents General Information History....................................................................................................................................1 Mission Statement ..................................................................................................................1 Statement of Principle on Diversity .......................................................................................2 Chronological History ............................................................................................................2 Accreditation ..........................................................................................................................3 Board of Trustees ...................................................................................................................4 Administration (Executive Council) ......................................................................................4 -

Big 12 Football: Competitive Balance Before and After Realignment

Big 12 Football: Competitive Balance Before and After Realignment thesportjournal.org/article/big-12-football-competitive-balance-before-and-after-realignment/ U.S. Sports Academy July 8, 2016 Authors: Jeffrey S. Noble*, Martin M. Perline, G. Clayton Stoldt Institutional Affiliation of Authors: Wichita State University *Corresponding Author: Jeff Noble, Ed.D Department of Sport Management Wichita State University 1845 Fairmount Wichita, Kansas 67260-0127 Email: [email protected] Phone: (316)978-5442 Abstract Conference realignment among athletic programs that compete at the Division I level of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has been prevalent among various institutions over the past decade, particularly among institutions that sponsor football. The purpose of the study was to investigate the effects on competitive balance when a conference lost member institutions who chose to join other conferences, and then added new institutions to replace those which had departed. Specifically, the effects on competitive balance in football in the Big 12 Conference, which lost four members and replaced with two additional schools, were examined. Using the standard deviation as our measure of competitive balance it was discovered that competition among the football programs were not as competitively balanced as before the initial realignment began. Keywords: college athletics, conference realignment, economic inequality Introduction Since the early 1990s numerous NCAA Division I athletic programs have changed their conference affiliation. The reasons for these changes in conference membership, often referred to as member churning, are myriad, ranging from political squabbles (13, 32) to opportunities to better position themselves for championship competition (20). There are 1/12 also ethical dimensions to competitive balance in college sports, as providing a level playing field for member institutions is one of the goals of athletic conferences (25, 28). -

2020 Standings Acc Football Notes 2020 Schedule (Oct. 17

As of Oct. 12 2020 STANDINGS ACC FOOTBALL NOTES ACC Games Overall THREE ACC TEAMS IN THE TOP 5 FOR FIRST TIME IN Team W L For Opp Pct W L For Opp Pct Home Away Neut Streak LEAGUE HISTORY Clemson 3 0 120 53 1.000 4 0 169 53 1.000 3-0 1-0 0-0 Won 4 • For the first time in league history, three ACC teams North Carolina 3 0 113 73 1.000 3 0 113 73 1.000 2-0 1-0 0-0 Won 6 are ranked in the AP Top 5 – No. 1 Clemson, No. 4 Notre Dame 2 0 69 39 1.000 3 0 121 39 1.000 3-0 0-0 0-0 Won 9 Notre Dame and No. 5 North Carolina. This is the 16th time in ACC history that three teams have been in the NC State 3 1 137 137 .750 3 1 137 137 .750 1-0 2-1 0-0 Won 2 top 10. Boston College 2 1 79 62 .667 3 1 103 83 .750 2-1 1-0 0-0 Won 1 Miami 2 1 116 86 .667 3 1 147 100 .750 2-0 1-1 0-0 Lost 1 • Five ACC teams are ranked in the AP Top 25 and USA Virginia Tech 2 1 128 111 .667 2 1 128 111 .667 1-0 1-1 0-0 Lost 1 Today/Amway Coaches Top 25 polls. In both polls, Georgia Tech 2 1 82 77 .667 2 2 103 126 .500 1-1 1-1 0-0 Won 1 Clemson is No. -

2007 VIRGINIA TECH FOOTBALL 1 the Hokies Had Seven Players

Eddie Royal second-team All-ACC Brandon Flowers first-team All-ACC and third-team All-American The Hokies had seven players honored by the always-competitive Atlantic Coast Conference a year ago 2007 VIRGINIA TECH FOOTBALL 71 4 the acc and opponents ACC Tradition of Excellence The Tradition that take to the field this fall winning percentage in Division placed in NCAA post-season Consistency. It is the mark of under the ACC banner have I-A history among teams with 15 competition in 2006-07. League true excellence in any endeavor. produced 523 first or second team or more post season appearances. teams compiled a 102-64-7 (.610) However, in today’s gridiron All-Americans and 72 first The Eagles are 12-6-0 (.667), mark against non-conference intercollegiate athletics, team academic All-Americans. while the Nittany Lions are 25- opponents in NCAA championship competition has become so Led by Georgia Tech wide 12-2 (.667). Georgia Tech, with competition. In addition, the ACC balanced and so competitive receiver Calvin Johnson, the a 22-13 (.629) bowl game mark, had 181 student-athletes earn that it is virtually impossible second overall selection by the is fifth and Florida State 21-13-2 first team All-America honors this to maintain a high level of Detroit Lions, the ACC had 31 (.611) seventh. past year. Overall, the league had consistency. players selected in the 2007 NFL For the first time in ACC 247 first, second or third team Yet the Atlantic Coast draft, including six first round history, league schools surpassed All-Americans. -

The History of Wake Forest University (1983–2005)

The History of Wake Forest University (1983–2005) Volume 6 | The Hearn Years The History of Wake Forest University (1983–2005) Volume 6 | The Hearn Years Samuel Templeman Gladding wake forest university winston-salem, north carolina Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data Names: Gladding, Samuel T., author. Title: History of Wake Forest University Volume 6 / Samuel Templeman Gladding. Description: First hardcover original edition. | Winston-Salem [North Carolina]: Library Partners Press, 2016. | Includes index. Identifiers: ISBN 978-1-61846-013-4. | LCCN 201591616. Subjects: LCSH: Wake Forest University–History–United States. | Hearn, Thomas K. | Wake Forest University–Presidents–Biography. | Education, Higher–North Carolina–Winston-Salem. |. Classification: LCCLD5721.W523. | First Edition Copyright © 2016 by Samuel Templeman Gladding Book jacket photography courtesy of Ken Bennett, Wake Forest University Photographer ISBN 978-1-61846-013-4 | LCCN 201591616 All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form. Produced and Distributed By: Library Partners Press ZSR Library Wake Forest University 1834 Wake Forest Road Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27106 www.librarypartnerspress.org Manufactured in the United States of America To the thousands of Wake Foresters who, through being “constant and true” to the University’s motto, Pro Humanitate, have made the world better, To Claire, my wife, whose patience, support, kindness, humor, and goodwill encouraged me to persevere and bring this book into being, and To Tom Hearn, whose spirit and impact still lives at Wake Forest in ways that influence the University every day and whose invitation to me to come back to my alma mater positively changed the course of my life. -

Conference Realignment in the FBS and Game-Day Football Attendance: Another Look

Falls, G. A. & Natke, P. A. (2020). Conference realignment in the FBS and game-day football attendance: Another look. Journal of Sports Economics & Management, 10(2), 64-82. CONFERENCE REALIGNMENT IN THE FBS AND GAME-DAY FOOTBALL ATTENDANCE: ANOTHER LOOK La reorganización de las conferencias en la FBS y la asistencia a los partidos de fútbol: Otra mirada Gregory A. Falls, Paul A. Natke Department of Economics, Central Michigan University, USA ABSTRACT: Sixteen Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) teams that changed conferences during 2004-2010 were used to estimate Tobit regression models via panel methods to examine if realignment affects home-game attendance. A conference change decreases attendance when an instrumented real ticket price is included in the pooled sample. When price is removed from the equation the conference change coefficient is insignificant. The model then is estimated for each post-change year. All coefficients for the conference change variable are insignificant. Second-mover advantages appear to be absent from this group of second-wave conference changers. Also absent is any evidence of a “honeymoon” effect. KEY WORDS: College football, game-day attendance, stadium utilization, conference realignment RESUMEN: Se utilizaron dieciséis equipos de la Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) que cambiaron de conferencia entre 2004 y 2010 para estimar modelos de regresión Tobit mediante métodos de panel y examinar si la realineación afecta a la asistencia a los partidos en casa. Un cambio de conferencia disminuye la asistencia cuando se incluye en la muestra agrupada un precio real de las entradas instrumentado. Cuando se elimina el precio de la ecuación, el coeficiente del cambio de conferencia no es significativo. -

The Bowl Championship Series: Money and Other Issues of Fairness for Publicly Financed Universities

THE BOWL CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES: MONEY AND OTHER ISSUES OF FAIRNESS FOR PUBLICLY FINANCED UNIVERSITIES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, TRADE, AND CONSUMER PROTECTION OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MAY 1, 2009 Serial No. 111–34 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce energycommerce.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–883 WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 13:33 Apr 26, 2012 Jkt 072883 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\A883.XXX A883 erowe on DSK2VPTVN1PROD with HEARING COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HENRY A. WAXMAN, California, Chairman JOHN D. DINGELL, Michigan JOE BARTON, Texas Chairman Emeritus Ranking Member EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts RALPH M. HALL, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia FRED UPTON, Michigan FRANK PALLONE, JR., New Jersey CLIFF STEARNS, Florida BART GORDON, Tennessee NATHAN DEAL, Georgia BOBBY L. RUSH, Illinois ED WHITFIELD, Kentucky ANNA G. ESHOO, California JOHN SHIMKUS, Illinois BART STUPAK, Michigan JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ROY BLUNT, Missouri GENE GREEN, Texas STEVE BUYER, Indiana DIANA DEGETTE, Colorado GEORGE RADANOVICH, California Vice Chairman JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania LOIS CAPPS, California MARY BONO MACK, California MICHAEL F. DOYLE, Pennsylvania GREG WALDEN, Oregon JANE HARMAN, California LEE TERRY, Nebraska TOM ALLEN, Maine MIKE ROGERS, Michigan JAN SCHAKOWSKY, Illinois SUE WILKINS MYRICK, North Carolina HILDA L. -

Factors Affecting and Theoretical Considerations

MAKING THE SWITCH: FACTORS AFFECTING AND THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT ATHLETIC CONFERENCE REALIGNMENT IN FBS INSTITUTIONS By DENNIS ALLAN KRAMER II (Under the Direction of Robert K. Toutkoushian) ABSTRACT Over the past ten years postsecondary institutions responded to the growing popularity of intercollegiate athletics by realigning with new athletic conferences. The public discourse on the reasons for these changes centers solely on athletic financial gain. However, institutional leaders and athletic administrators have long discussed the complexities and information rich nature of athletic conference realignment decisions. In the face of these complexities, few scholars have investigated the athletic conference realignment process. Thus, this study utilized a case study qualitative methodology to investigate the factors influencing athletic conference realignment and the role various campus actors played in the decision-making process. Using various organizational theories to frame the discussion of results, this study finds that access to additional conference revenue, increasing institutional visibility, and alignment with strategic peer institutions drove the athletic conference realignment process. While institution officials acknowledge a distinct set of reasons for engaging in athletic conference realignment, they also presented differences experienced in the strategic decision-making process. Results indicate institutions already placed within a powerful athletic conference experiences different incentives than those moving -

2010 Football Season

22010010 FFootball:ootball: TThehe RRoadoad TToo TThehe OOrangerange BBowlowl GGoesoes TThroughhrough CCharlotteharlotte The Atlantic Coast Conference What’s Inside ACC Standings: 2009 Final Standings Release No. 1, Friday, August 27, 2010 ACC Games Overall ACC SIDs, ACC Communications .........2 Atlantic Division ..W L ..For Opp Hm Rd ..W L ....For Opp Hm Rd Nu Div. ... Streak Media Schedule, Digital News............3 #Clemson ...............6 2 ..268 169 4-0 2-2 ....9 5 ....436 286 6-1 2-3 1-1 4-1 ......Won 1 ACC National and Satellite Radio ........4 Boston College .......5 3 ..174 196 3-1 2-2 ....8 5 ....322 257 6-1 2-3 0-1 4-1 ......Lost 1 2010 Composite Schedule .................5 Florida State ...........4 4 ..268 278 2-2 2-2 ....7 6 ....391 390 3-3 3-3 1-0 3-2 ......Won 1 ACC By The Numbers Notes ...............6 Wake Forest ...........3 5 ..226 254 2-2 1-3 ....5 7 ....316 315 4-3 1-4 0-0 2-3 ......Won 1 Atlantic, Coastal Division Notes ...... 7-8 NC State .................2 6 ..213 315 2-2 0-4 ....5 7 ....364 374 5-3 0-4 0-0 1-4 ......Won 1 Week 1 Game Previews ................9-11 Maryland ................1 7 ..161 222 1-3 0-4 ....2 10 ....256 375 2-5 0-5 0-0 1-4 ......Lost 7 Team Schedule and Results......... 12-14 Noting ACC Football .................. 15-25 Coastal Division . W L ..For Opp Hm Rd ..W L ....For Opp Hm Rd Nu Div. ... Streak 2010 Dr Pepper ACC Championship ..