Two-Lane Blacktop 1971, EEUU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Road Movies of the 1960S, 1970S, and 1990S

Identity and Marginality on the Road: American Road Movies of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1990s Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies. © Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Abrégé …………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Acknowledgements …..………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Chapter One: The Founding of the Contemporary Road Rebel …...………………………...… 23 Chapter Two: Cynicism on the Road …………………………………………………………... 41 Chapter Three: The Minority Road Movie …………………………………………………….. 62 Chapter Four: New Directions …………………………………………………………………. 84 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………………………..... 90 Filmography ……………………………………………………………………………………. 93 2 Abstract This thesis examines two key periods in the American road movie genre with a particular emphasis on formations of identity as they are articulated through themes of marginality, freedom, and rebellion. The first period, what I term the "founding" period of the road movie genre, includes six films of the 1960s and 1970s: Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider (1969), Francis Ford Coppola's The Rain People (1969), Monte Hellman's Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Richard Sarafian's Vanishing Point (1971), and Joseph Strick's Road Movie (1974). The second period of the genre, what I identify as that -

Diciembreenlace Externo, Se Abre En

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 91 3691125 Fax: 91 4672611 (taquilla) [email protected] 91 369 2118 http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html (gerencia) Fax: 91 3691250 MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala diciembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2009 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 16.45 - 00.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.00 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico DICIEMBRE 2009 Monte Hellman Dario Argento Cine para todos - Especial Navidad Charles Chaplin (I) El nuevo documental iberoamericano 2000-2008 (I) La comedia cinematográfica española (II) Premios Goya (y V) El Goethe-Institut Madrid presenta: Ulrike Ottinger Buzón de sugerencias Muestra de cortometrajes de la PNR Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Two-Lane Blacktop 1971, AEB

Two-Lane Blacktop 1971, AEB urreko mendeko hirurogeiko hamarkada izan zen ordura arte Estatu Ba- Z: Monte Hellman; G: Rudy Atuetako eta munduko zinemaren patua gidatu zuten konpainia handien Wurlitzer, Will Corry (Historia: Will negozioaren puntu kritikoenetako bat. AEBko zinema-aretoen okupazioak Corry); Pr: Universal Pictures; M: sekulako beherakada izan zuen: 1930. urtean 110 milioi ikusle izan zituzten, Billy James; A: Jack Deerson; A: eta, berrogeita hamarreko hamarkadaren amaieran, 40 milioi izan ziren. Bi- James Taylor, Warren Oates, Laurie garren Mundu Gerra amaitu eta hurrengo urteetan ispilatze labur bat egon Bird, Dennis Wilson, David Brake; zen, sarreren salmenta bidezko diru-bilketak kopuru historikoak lortu zitue- Kolorea, 101 min. DCP nean, eta ikusleen kopurua 100 milioi pertsonakoa zen urtean. Une horretatik aurrera, ordea, parametro ekonomiko guztiek beherakada argi bat utzi zuten agerian. Arrazoi ugari zeuden horretarako, konplexuak: hasteko, 1948an, Es- tatu Batuetako Auzitegi Gorenak monopolioen aurkako epaia eman zuen, eta Hollywoodeko Major deritzenei integrazio bertikalaren politika alde batera uzteko betebeharra ezarri zien: politiko horien bidez, zinema-prozesu osoa kontrola zezaketen, estudioetako ekoizpenetik aretoetako erakusketara arte. Hala ere, mutazio garrantzitsuenak Estatu Batuetako gizarteak izan zi- tuen aldaketa soziologikoen ondorio izan ziren, bereziki biztanleria-nukleo garrantzitsuak hiri handietako periferiako egoitza-eremuetara iristen hasi zirenean; ondorioz, husten ari ziren hiri-zentroetan kokatutako “zinema-jau- regiak” publiko potentzialik gabe gelditu ziren, eta ezin ziren modu errenta- garrian ordezkatu aldirietan kokatutako drive-in deritzenengatik. Hori guz- tia gutxi balitz, entretenitzeko modu berri bat heldu zen: telebista. Horrek aukera ematen zuen ikus-entzunezko edukiak kontsumitzeko etxean bertan, sarrerarik ordaindu gabe, eta XX. mendean zehar hainbat belaunaldiren iru- diteria herrikoiaren oinarrizko iturria kontrolatu zuenaren arerio bihurtu zen. -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

Les Bad Boys De L'ouest : Brando, Nicholson Et Le Western

Document generated on 10/01/2021 5:32 p.m. 24 images Les Bad Boys de l’Ouest Brando, Nicholson et le Western Bruno Dequen Western – Histoires parallèles Number 186, March 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/87969ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Dequen, B. (2018). Les Bad Boys de l’Ouest : Brando, Nicholson et le Western. 24 images, (186), 18–19. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2018 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ DOSSIER — WESTERN – Histoires parallèles LES BAD BOYS DE L’OUEST BRANDO, NICHOLSON ET LE WESTERN par Bruno Dequen Le Western n’est pas le premier genre qui vient en tête à la mention des noms de Marlon Brando et Jack Nicholson. Pourtant, ils en ont tous deux réalisé un, et The Missouri Breaks demeure le seul film dans lequel ils ont partagé l’affiche. Critiquées ou ignorées à l’époque de leurs sorties, les incursions des deux monstres sacrés au Far West font partie des propositions les plus originales du genre et mettent en valeur la relation complexe qu’entretenaient les deux légendes d’Hollywood avec leur art. -

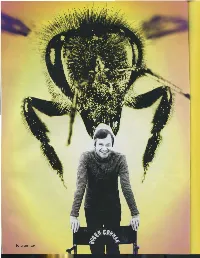

30 MENTAL FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA by IAN LENDLER

30 MENTAL_FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA BY IAN LENDLER MENTALFLOSS.COM 31 the Golden Age of Hollywood, big-budget movies were classy affairs, full of artful scripts and classically trained actors. And boy, were they dull. Then came Roger Corman, the King of the B-Movies. With Corman behind the camera, motorcycle gangs and mutant sea creatures .filled the silver screen. And just like that, movies became a lot more fun. .,_ Escape from Detroit For someone who devoted his entire life to creating lurid films, you'd expect Roger Corman's biography to be the stuff of tab loid legend. But in reality, he was a straight-laced workaholic. Having produced more than 300 films and directed more than 50, Corman's mantra was simple: Make it fast and make it cheap. And certainly, his dizzying pace and eye for the bottom line paid off. Today, Corman is hailed as one of the world's most prolific and successful filmmakers. But Roger Corman didn't always want to be a director. Growing up in Detroit in the 1920s, he aspired to become an engineer like his father. Then, at age 14, his ambitions took a turn when his family moved to Los Angeles. Corman began attending Beverly Hills High, where Hollywood gossip was a natural part of the lunchroom chatter. Although the film world piqued his interest Corman stuck to his plan. He dutifully went to Stanford and earned a degree in engineering, which he didn't particularly want. Then he dutifully entered the Navy for three years, which he didn't particularly enjoy. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Join Us. 100% Sirena Quality Taste 100% Pole & Line

melbourne february 8–22 march 1–15 playing with cinémathèque marcello contradiction: the indomitable MELBOURNE CINÉMATHÈQUE 2017 SCREENINGS mastroianni, isabelle huppert Wednesdays from 7pm at ACMI Federation Square, Melbourne screenings 20th-century February 8 February 15 February 22 March 1 March 8 March 15 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm Presented by the Melbourne Cinémathèque man WHITE NIGHTS DIVORCE ITALIAN STYLE A SPECIAL DAY LOULOU THE LACEMAKER EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Luchino Visconti (1957) Pietro Germi (1961) Ettore Scola (1977) Maurice Pialat (1980) Claude Goretta (1977) Jean-Luc Godard (1980) Curated by the Melbourne Cinémathèque. 97 mins Unclassified 15+ 105 mins Unclassified 15+* 106 mins M 101 mins M 107 mins M 87 mins Unclassified 18+ Supported by Screen Australia and Film Victoria. Across a five-decade career, Marcello Visconti’s neo-realist influences are The New York Times hailed Germi Scola’s sepia-toned masterwork “For an actress there is no greater gift This work of fearless, self-exculpating Ostensibly a love story, but also a Hailed as his “second first film” after MINI MEMBERSHIP Mastroianni (1924–1996) maintained combined with a dreamlike visual as a master of farce for this tale remains one of the few Italian films than having a camera in front of you.” semi-autobiography is one of Pialat’s character study focusing on behaviour a series of collaborative video works Admission to 3 consecutive nights: a position as one of European cinema’s poetry in this poignant tale of longing of an elegant Sicilian nobleman to truly reckon with pre-World War Isabelle Huppert (1953–) is one of the most painful and revealing films. -

Index Des Revues Des Cahiers Du Cinéma, Óþóõ

Index des revues des Cahiers du Cinéma, óþóÕ Les ó Alfred de Bruno Podalydès . ßßó Ch. G. ¢þ–¢Õ Le Õ¢ h Õß pour Paris deClintEastwood ........................... ßߦ M. M. ß–ßÉ Õ¦ì rue du désert d’Hassen Ferhani . ßßß M. M. Õ¦–Õ¢, C. A. Õ¢–Õä óþþ mètres d’AmeenNayfeh ........................................ ßßß M. M. ì¦ À l’abordage de Guillaume Brac . ßßä O. C.-H. ó¦–ó¢, C. A., E. M. óä–óÉ, C. A., E. M. ìþ–ìó, M. U. ìì–ì¢, P.F. ìä–ìß À nos amours de Maurice Pialat . ßß P.B. Õìó–Õì¢ L’Aaire collective d’Alexander Nanau . ßßÉ R. P. ì Aer Love d’AleemKhan ............................................ ßßÉ L. S. ¦¦ L’Amour existe de Maurice Pialat . ßß M. U. ÕÕß–ÕÕ Les Amours d’Anaïs de Charline Bourgeois-Tacquet . ßßÉ O. C.-H. ìä e Amusement Park deGeorgeA.Romero ............................ ßßß É. L. ìþ Annette de Leos Carax . ßß M. U. Õó–Õ¦, P.F., M. U. Õä–Õß, Ch. G., M. U. Õ–óì, E. K. ó¦, É. T. óä El año del descubrimiento de Luis López Carrasco . ßßó É. T. ¦ä Army of the Dead de Zack Snyder . ßßß Y.S. ¦ì–¦¦ Autour de Jeanne Dielman de Sami Frey . ßßì P.L. äþ–äÕ Aya et la sorcière de Goro Miyazaki . ßß M. M. ¢¦ Bac Nord de Cédric Jimenez . ßß O. C.-H. ¢¦ Back Door to Hell deMonteHellman ............................... ßßß Y.S. –É La Bataille du rail de Jean-Charles Paugam . ßß R. N. ¢¦ Beast from Haunted Cave deMonteHellman ........................ ßßß J.-M. S. Beef House d’Eric Wareheim et Tim Heidecker . -

The Museum of Modern Art Department of Film

The Museum of Modern Art Department of Film 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART THE ARTS FOR TELEVISION an exhibition organized by The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam THE ARTS FOR TELEVISION is the first major museum exhibition to examine television as a form for contemporary art : television as a gallery or theater or alternative space, even television as art . An international selection of artworks made for broadcast, the exhibi- tion documents the crossovers and collaborations that take place on this new television, between and among dancers, musicians, play- wrights, actors, authors, poets, and visual and video artists . And it investigates the artists' own investigation of one medium -- be it dance or music or literature -- through another . It examines the transformations video makes and the possibilities it allows . These provocative uses of television time and technology are organized in THE ARTS FOR TELEVISION according to the medium transformed by the electronic image ; the six categories are Dance for Television, Music for Television, Theatre for Television, Literature for Television, The Video Image (works that address video as a visual art, that make reference to the traditional visual arts and to seeing itself), and Not Necessarily Television (works that address the usual content of TV, and transform it) . The ARTS FOR TELEVISION also presents another level of collaboration in artists' television . It documents the involvement of television stations in Europe and America with art and artists' video . It recognizes their commitment and acknowledges the risks they take in allowing artists the opportunity to realize works of art . -

Two-Lane Blacktop by Sam Adams “The B List: the National Society of Film Critics on the Low-Budget Beauties, Genre-Bending Mavericks, and Cult Clas- Sics We Love”

Courtesy Library of Congress Two-Lane Blacktop By Sam Adams “The B List: The National Society of Film Critics on the Low-Budget Beauties, Genre-Bending Mavericks, and Cult Clas- sics We Love” Reprinted by permission of the author Racing flat-out on the road to no- where, the scrawny speed demons of “Two-Lane Blacktop” are caught be- tween a past they’ve never known and a future they’ll never see. The Driver (James Taylor) and the Me- chanic (Dennis Wilson) act the part of rebels from a ‘50s exploitation movie, but their sallow skin and sunken eyes reveal the gnawing uncertainty of a Laurie Bird, James Taylor and Dennis Wilson strike a pose with another of the film’s stars: disillusioned age, a longing for a the Chevy. Courtesy Library of Congress sense of purpose that exists only in the seconds between starting flag and finish line. Oates), whose slick patter spills out in bewildering chunks. (the credits call him “G.T.O.” although the char- Universal, which handed director Monte Hellman nine acters never address each other by name.) The route hundred thousand dollars to make his first (and, as it (Arizona to DC) is set, the stakes (pink slips) agreed upon, turned out, only) studio movie, must have hoped for a and the cars peel out, intending to drive straight through. youth-culture paean in the “Easy Rider” mode. Although neither of the movie’s leads had acted before, both were But a series of pit stops and small-town diversions turns stars in their own right” Wilson was the Beach Boys’ their breakneck dash into a roadside odyssey, a trave- drummer and Taylor was a budding soft-rock superstar.