A Dynamic Fragmentation of the Misery Index in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection: Vertical File, Ronald Reagan Library Folder Title: Reagan, Ronald W

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Vertical File, Ronald Reagan Library Folder Title: Reagan, Ronald W. – Promises Made, Promises Kept To see more digitized collections visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digitized-textual-material To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/white-house-inventories Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/research- support/citation-guide National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ . : ·~ C.. -~ ) j/ > ji· -·~- ·•. .. TI I i ' ' The Reagan Administration: PROMISES MADE PROMISES KEPI . ' i), 1981 1989 December, 1988 The \\, hile Hollst'. Offuof . Affairs \l.bshm on. oc '11)500 TABIE OF CDNTENTS Introduction 2 Economy 6 tax cuts 7 tax reform 8 controlling Government spending 8 deficit reduction 10 ◄ deregulation 11 competitiveness 11 record exports 11 trade policy 12 ~ record expansion 12 ~ declining poverty 13 1 reduced interest rates 13 I I I slashed inflation 13 ' job creation 14 1 minority/wmen's economic progress 14 quality jobs 14 family/personal income 14 home ownership 15 Misery Index 15 The Domestic Agenda 16 the needy 17 education reform 18 health care 19 crime and the judiciary 20 ,,c/. / ;,, drugs ·12_ .v family and traditional values 23 civil rights 24 equity for women 25 environment 26 energy supply 28 transportation 29 immigration reform 30 -

Abigail P. Dumalus December 2018 Macroeconomics of Life Satisfaction

Abigail P. Dumalus December 2018 Macroeconomics of Life Satisfaction Inequality (Working Paper, Unpublished) Abstract Not much is known about the variations that macroeconomic movements bring to the significance of how people’s subjective life satisfaction (LS) assessments are aggregately distributed. Now more than ever, leaders, policymakers, academia, the media, and the general public may find it worthwhile to know more about LS inequality. The question “How do macroeconomic shifts influence LS inequality?” is closely examined. Whereas most subjective well-being (SWB) studies in economic literature have been dealing with causes and consequences of overall happiness across societies, this paper investigates the macroeconomics of LS inequality. Using internationally comparable upward-looking LS inequality and measures of macroeconomic shifts within a nested cross-country dataset, robust and conclusive empirical evidence is provided to highlight the fundamental role of macroeconomic movements in shaping perceived differences in LS. Findings in this research adequately bolster the substance of how such changes in the macroeconomic landscape have a bearing on shaping SWB or happiness on the aggregate level. Results also carefully explore how disparities in well-being are adversely or favorably motivated by extreme LS responses due to macroeconomic fluctuations. This study makes a twofold contribution to the literature on the effects of macroeconomic movements on well-being. First, using the Cowell-Flachaire status-inequality method, this paper constructs the first multi-country estimate of LS inequality, which could be a more suitable measure of overall welfare. The distribution of LS illustrates a more inclusive and substantial investigation of the impacts of any inequalities that may spring from macroeconomic shifts in society. -

Fordham University ECON 3235 Darryl Mcleod Latin American Economies Fall 2019 Syllabus V1 8-26-2019

Fordham University ECON 3235 Darryl McLeod Latin American Economies Fall 2019 Syllabus v1 8-26-2019 Course Description: This is a wonderful time to study Latin America’s wondrously diverse and challenging economies. Many LatAm countries are in the tropics, hence Puerto Rico battles devastating hurricane Maria while Brazil fights Amazon fires. Drug relate violence roils Mexico and Central America leading many to flee North. Yet in terms of equity and social mobility Latin America has outperformed the U.S. as since 2000 virtually every major LatAm economy experienced a “golden decade” of falling poverty and inequality and rising social mobility as a new resilient middle class emerged. Colombia, once plagued with storied violent drug lords, cartels and corruption (see Narcos seasons 1-3) has emerged from a long civil war and now shelters 1.2 million plus desperate Venezuelan immigrants. Many LatAm countries (Costa Rica for example) seem to happy if not rich, this is the Easterlin paradox: more happiness with less income per person. We hope so. A century ago Argentina was among the World’s 10 richest countries, since then it has fallen into the 80s. Still if you have visited Argentina recently, especially Buenos Aires, you know their subway looks exactly like New York’s but works better with lower fares. Venezuela on the other hand is an economic and social (humanitarian) nightmare. With inflation of 10 million percent plus we can’t even computer Venezuela’s misery index (inflation + the unemployment rate). Malnutrition is now widespread in what was a decade ago one of the richest LatAm countries… how has this unfathomable tragedy befallen a wonderful people? Whose can we blame? How can we fix it? You tell me (a great case study, many bonus points for even trying). -

Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress

Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Professor Joseph E. STIGLITZ, Chair, Columbia University Professor Amartya SEN, Chair Adviser, Harvard University Professor Jean-Paul FITOUSSI, Coordinator of the Commission, IEP www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr Other Members Bina AGARWAL University of Delhi Kenneth J. ARROW StanfordUniversity Anthony B. ATKINSON Warden of Nuffield College François BOURGUIGNON School of Economics, Jean-Philippe COTIS Insee, Angus S. DEATON Princeton University Kemal DERVIS UNPD Marc FLEURBAEY Université Paris 5 Nancy FOLBRE University of Massachussets Jean GADREY Université Lille Enrico GIOVANNINI OECD Roger GUESNERIE Collège de France James J. HECKMAN Chicago University Geoffrey HEAL Columbia University Claude HENRY Sciences-Po/Columbia University Daniel KAHNEMAN Princeton University Alan B. KRUEGER Princeton University Andrew J. OSWALD University of Warwick Robert D. PUTNAM Harvard University Nick STERN London School of Economics Cass SUNSTEIN University of Chicago Philippe WEIL Sciences Po Rapporteurs Jean-Etienne CHAPRON INSEE General Rapporteur Didier BLANCHET INSEE Jacques LE CACHEUX OFCE Marco MIRA D’ERCOLE OCDE Pierre-Alain PIONNIER INSEE Laurence RIOUX INSEE/CREST Paul SCHREYER OCDE Xavier TIMBEAU OFCE Vincent MARCUS INSEE Table of contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. SHORT NARRATIVE ON THE CONTENT OF THE REPORT Chapter 1: Classical GDP Issues . 21 Chapter 2: Quality of Life . 41 Chapter 3: Sustainable Development and Environment . 61 II. SUBSTANTIAL ARGUMENTS PRESENTED -

Japanese Overseas School) in Belgium: Implications for Developing Multilingual Speakers in Japan

Language Ideologies on the Language Curriculum and Language Teaching in a Nihonjingakkō (Japanese overseas school) in Belgium: Implications for Developing Multilingual Speakers in Japan Yuta Mogi Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UCL-Institute of Education 2020 1 Statement of originality I, Yuta Mogi confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where confirmation has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Yuta Mogi August, 2020 Signature: ……………………………………………….. Word count (exclusive of list of references, appendices, and Japanese text): 74,982 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Siân Preece. Her insights, constant support, encouragement, and unwavering kindness made it possible for me to complete this thesis, which I never believed I could. With her many years of guidance, she has been very influential in my growth as a researcher. Words are inadequate to express my gratitude to participants who generously shared their stories and thoughts with me. I am also indebted to former teachers of the Japanese overseas school, who undertook the roles of mediators between me and the research site. Without their support in the crucial initial stages of my research, completion of this thesis would not have been possible. In addition, I am grateful to friends and colleagues who were willing readers and whose critical, constructive comments helped me at various stages of the research and writing process. Although it is impossible to mention them all, I would like to take this opportunity to offer my special thanks to the following people: Tomomi Ohba, Keiko Yuyama, Takako Yoshida, Will Simpson, Kio Iwai, and Chuanning Huang. -

Professor William J

Fordham University Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series Will the global financial crisis lead to lower foreign aid? A first look at United States ODA Ronald U. Mendoza UNICEF, Division of Policy and Practice, Social Policy and Economic Analysis Unit Ryan Jones Fordham University, Department of Economics, International Political Economy and Development (IPED) Program Gabriel Vergara Fordham University, Department of Economics, International Political Economy and Development (IPED) Program Discussion Paper No: 2009-01 January 2009 Department of Economics Fordham University 441 E Fordham Rd, Dealy Hall Bronx, NY 10458 (718) 817-4048 Will the global financial crisis lead to lower foreign aid? A first look at United States ODA Ronald U. Mendoza*, Ryan Jones** and Gabriel Vergara** DISCUSSION DRAFT January 2009 ABSTRACT Analyzing US economic and foreign aid data from 1967 to 2007, this paper investigates whether adverse economic and financial conditions are negatively linked to official development assistance (ODA). It finds empirical evidence that US ODA has tended to decline as its economic conditions worsen. A 1 unit increase in the misery index (sum of inflation and unemployment) is associated with a roughly 0.01 percentage point decline in US ODA expressed as a share of GNI. Furthermore, an increase in financial volatility from 1 percent to 2 percent (measured by the standard deviation of the rate of return of the S&P500) is associated with a decrease in US ODA by about $2.78 billion. Informed by the empirical results in this paper, and based on very rough guesstimates, a potential decline in US ODA of anywhere from 13 to 30 percent could occur depending on the severity of the economic conditions in 2009. -

Okun's and Barro's Misery Index As

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Munich RePEc Personal Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Okun`s and Barro`s Misery Index as an alternative poverty assessment tool. Recent estimations for European countries. Lechman Ewa Faculty of Management and Economics, Gdansk University of Technology 2009 Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/37493/ MPRA Paper No. 37493, posted 20. March 2012 14:20 UTC Okun`s and Barro`s Misery Index as an alternative poverty assessment tool. Recent estimations for European countries. Ewa Lechman1 Published in: Growth and innovation - selected issues. Monograph. Gdańsk, 2009 Key words: povety, poverty measurement, European countries, Misery Index. JEL codes: I32 “The higher this index2, the greater the discomfort – we`re less pained by inflation if the job market is jumping, and less sensitive to others` unemployment if a placid price level is widely enjoyed” Richard F. Janssen3 1. Introduction Poverty and all related problems, usually lie in the very centre of public interest. Poverty reduction strategies, as these which may be a good panacea for solving many of social problems that today’s societies have to deal with should be constructed carefully and on proper basis. One of the “basis” should be applying such poverty assessment method (closely related to measurement methods) that would reflect real magnitude of poverty in a given economy. It might be strange but poverty perceiving and understanding and measurement depends mostly on country`s specific condition and its general welfare. 2. Poverty, its measurement and Misery Index – theoretical background In poor and underdeveloped economies widely used measure for poverty assessment are two arbitrary set poverty lines developed by World Bank. -

David G. Blanchflower David N.F. Bell Alberto Montagnoli Mirko Moro

The effects of macroeconomic shocks on well-being David G. Blanchflower Bruce V. Rauner Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Dartmouth College, Division of Economics, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Federeal Reserve Bank of Boston, Peterson Institute for International Economics, IZA, CESifo and NBER David N.F. Bell Division of Economics Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, IZA and CPC Alberto Montagnoli Division of Economics Stirling Management School, University of Stirling Mirko Moro Division of Economics Stirling Management School, University of Stirling and ESRI 18th March 2013 Abstract Previous literature has found that both unemployment and inflation lower happiness. The macroeconomist Arthur Okun characterised the negative effects of unemployment and inflation by the misery index - the sum of the unemployment and inflation rates. This paper extends the literature by looking at more countries over a longer time period. We find, conventionally, that both higher unemployment and higher inflation lower happiness. We also discover that unemployment depresses well-being more than inflation. We characterise this wellbeing trade-off between unemployment and inflation using what we describe as the misery ratio. Our estimates with European data imply that a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate lowers well being by two and a half times as much as a one percentage point increase in the inflation rate. We also find that banking crises lower individual well-being, including crises before the Great Recession. Keywords Inflation, Misery-index, Unemployment, Well-being, Banking crises Unemployment and inflation are major targets of macroeconomic policy, presumably because policymakers believe that a higher level of either variable has an adverse effect on welfare. -

Effect of Fiscal Policy on Misery Index in Nigeria

European Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 9 No. 1, 2021 ISSN 2056-5429 EFFECT OF FISCAL POLICY ON MISERY INDEX IN NIGERIA Dr. Anaele, Augustine Adindu Department of Economics Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt & Dr. Nyenke, Christian Ugondah Department of Economics Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt ABSTRACT This study examined the effect of fiscal policy on misery index in Nigeria from 1981 to 2018. The fiscal policy variables such as government capital expenditure (GCEX), government recurrent expenditure (GREX) and government external debt (GEDT) was used. Dummy variable to capture the effects of policy shift on misery index in Nigeria. Direct policy was coded zero (0) while indirect or market based policy was coded one (1). Misery index was measured by the sum of unemployment, inflation and lending rates less growth rate of real GDP per capita. This study adopted the ordinary least square (OLS) method of regression analysis. The study conducted some other tests such as: R2, T-test, F-test, DW-tests, Philip Perron (PP) unit root test, Johansen cointergation test and error correction mechanism (ECM). From the results of the analysis, it was shown that government capital expenditure (GCEX), government recurrent expenditure (GREX) and government external debt (GEDT) conformed to the Keynesian theory of government expenditure. That is, increase in government capital expenditure (GCEX) and government recurrent expenditure (GREX) reduced misery index in Nigeria in the current period. It implies that rising external debt in current period worsened misery index in Nigeria. The analysis further revealed that the fiscal policy alone under the current regime of market based policy performed poorly in tackling economic misery in Nigeria due to the fact that it is insignificant. -

Decomposing the Misery Index: a Dynamic Approach

Decomposing the misery index: A dynamic approach Item Type Article Authors Cohen, I.K.; Ferretti, F.; McIntosh, Bryan Citation Cohen IK, Ferretti F and McIntosh B (2016) Decomposing the misery index: A dynamic approach. Cogent Economics and Finance. 2. Rights © 2014 The Author(s). This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) 3.0 license. Download date 26/09/2021 05:50:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/9907 The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published online version may require a subscription. Link to publisher’s version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2014.991089 Citation: Cohen IK, Ferretti F and McIntosh B (2016) Decomposing the misery index: A dynamic approach. Cogent Economics and Finance. 2. Copyright statement: © 2014 The Author(s). This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) 3.0 license. Cohen et al., Cogent Economics & Finance (2014), 2: 991089 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2014.991089 GENERAL & APPLIED ECONOMICS | LETTER Decomposing the misery index: A dynamic approach Ivan K. Cohen1, Fabrizio Ferretti2,3* and Bryan McIntosh4 Received: 17 October 2014 Abstract: The misery index (the unweighted sum of unemployment and inflation Accepted: 19 November 2014 rates) was probably the first attempt to develop a single statistic to measure the level *Corresponding author, Fabrizio Ferretti, of a population’s economic malaise. -

The Gap Between Reality and Perception

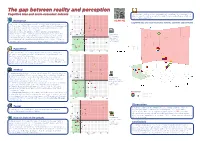

TheThe gapgap betweenbetween realityreality andand perceptionperception Cognitive bias and socio-economic indexes Relating the 5 variables in the same graph and using flag size to represent the bias, we expect countries closer to the origin to have smaller flags and further ones to have bigger flags. Motivation SCAN ME 2 Cognitive bias and socio-economic indexes, countries (22) selected The strong contrast between accessibility to information and perception of reality is a current topic. The expression cognitive bias refers to a judgement developed on interpretation of information not logically related to each other that brings to a mistake in evaluation. 1 Think about bias as the distance between what is real and what we think it is. The concept of bias was born at the beginning of ‘70s, thanks Correlation to psychologists Kahneman and Tversky; their researches showed that 0,24 (weak) 0 individuals act using mental shortcuts instead of rational processes. In Press freedom/ 2002 Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics, for having cognitive bias incorporated the results from decisional psychology into economic science. (38 countries) −1 Hypothesis −1 0 1 2 3 Cognitive bias has to be considered a relevant issue in the algorithmic information era, where our beliefs (often wrong) are reaffirmed by the inputs we receive from the media. Given that rational inability to elaborate information is structurally present in individuals, we assume that its intensity grows in the following situations: poor education (and critical thinking), economic difficulty (social 2 destabilisation) and control over information. Method 1 The aggregated data refer to 38 countries in the year 2017. -

Estimating Barro Misery Index in Democratic States with Application in Albania: 2005 – 2014

ISSN 2411-958X (Print) European Journal of January-April 2016 ISSN 2411-4138 (Online) Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 2, Issue 2 Estimating Barro misery index in democratic states with application in Albania: 2005 – 2014 Prof. Dr Fejzi Kolaneci University of New York, Tirana, Albania, fkolaneci@unyt. edu. al Juxhen Duzha University of New York, Tirana, Albania juxhenduzha@hotmail. com Enxhi Lika Universiteti i Tiranës, Fakulteti Ekonomik, Albania Enxhilika15@hotmail. com “The Barro misery index accurately measures misery” Steve H. Hanke “The higher Barro misery index, the greater the economic and social discomfort” Richard F. Janssen Abstract In the present study we develop a statistical analysis of the Barro misery index and its components in contemporary democratic states with application in Republic of Albania during the period January 2005- December 2014. BMI is calculated by the formula: BMI = π + u – GPD + i, where BMI denotes quarterly Barro misery index, π denotes quarterly inflation rate, u denotes quarterly unemployment rate, GDP denotes quarterly real GDP growth rate, i denotes nominal long-term interest rate. Kolmogorov’s Central Limit Theorem is a fundamental theorem of Modern Probability Theory “Fair game” and “Effective market in week sense” are important concepts of Macroeconomics. Some results of the study include : Kolmogorov’s Central Limit Theorem is not valid for quarterly inflation rates in Albania during the period January 2005- December 2014 at the confidence 99. 9%. 141 ISSN 2411-958X (Print) European Journal of January-April 2016 ISSN 2411-4138 (Online) Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 2, Issue 2 The inflation process in Albania during the specified period, related to the quarterly inflation rate, is an unfair game at the confidence 98.