The Boolfun Package : Cryptographic Properties of Boolean Functions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vector Boolean Functions: Applications in Symmetric Cryptography

Vector Boolean Functions: Applications in Symmetric Cryptography José Antonio Álvarez Cubero Departamento de Matemática Aplicada a las Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones Universidad Politécnica de Madrid This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor Ingeniero de Telecomunicación Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicación November 2015 I would like to thank my wife, Isabel, for her love, kindness and support she has shown during the past years it has taken me to finalize this thesis. Furthermore I would also liketo thank my parents for their endless love and support. Last but not least, I would like to thank my loved ones such as my daughter and sisters who have supported me throughout entire process, both by keeping me harmonious and helping me putting pieces together. I will be grateful forever for your love. Declaration The following papers have been published or accepted for publication, and contain material based on the content of this thesis. 1. [7] Álvarez-Cubero, J. A. and Zufiria, P. J. (expected 2016). Algorithm xxx: VBF: A library of C++ classes for vector Boolean functions in cryptography. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. (In Press: http://toms.acm.org/Upcoming.html) 2. [6] Álvarez-Cubero, J. A. and Zufiria, P. J. (2012). Cryptographic Criteria on Vector Boolean Functions, chapter 3, pages 51–70. Cryptography and Security in Computing, Jaydip Sen (Ed.), http://www.intechopen.com/books/cryptography-and-security-in-computing/ cryptographic-criteria-on-vector-boolean-functions. (Published) 3. [5] Álvarez-Cubero, J. A. and Zufiria, P. J. (2010). A C++ class for analysing vector Boolean functions from a cryptographic perspective. -

A Quantitative Study of Advanced Encryption Standard Performance

United States Military Academy USMA Digital Commons West Point ETD 12-2018 A Quantitative Study of Advanced Encryption Standard Performance as it Relates to Cryptographic Attack Feasibility Daniel Hawthorne United States Military Academy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/faculty_etd Part of the Information Security Commons Recommended Citation Hawthorne, Daniel, "A Quantitative Study of Advanced Encryption Standard Performance as it Relates to Cryptographic Attack Feasibility" (2018). West Point ETD. 9. https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/faculty_etd/9 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by USMA Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Point ETD by an authorized administrator of USMA Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A QUANTITATIVE STUDY OF ADVANCED ENCRYPTION STANDARD PERFORMANCE AS IT RELATES TO CRYPTOGRAPHIC ATTACK FEASIBILITY A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Computer Science By Daniel Stephen Hawthorne Colorado Technical University December, 2018 Committee Dr. Richard Livingood, Ph.D., Chair Dr. Kelly Hughes, DCS, Committee Member Dr. James O. Webb, Ph.D., Committee Member December 17, 2018 © Daniel Stephen Hawthorne, 2018 1 Abstract The advanced encryption standard (AES) is the premier symmetric key cryptosystem in use today. Given its prevalence, the security provided by AES is of utmost importance. Technology is advancing at an incredible rate, in both capability and popularity, much faster than its rate of advancement in the late 1990s when AES was selected as the replacement standard for DES. Although the literature surrounding AES is robust, most studies fall into either theoretical or practical yet infeasible. -

Constructing Low-Weight Dth-Order Correlation-Immune Boolean Functions Through the Fourier-Hadamard Transform Claude Carlet and Xi Chen*

1 Constructing low-weight dth-order correlation-immune Boolean functions through the Fourier-Hadamard transform Claude Carlet and Xi Chen* Abstract The correlation immunity of Boolean functions is a property related to cryptography, to error correcting codes, to orthogonal arrays (in combinatorics, which was also a domain of interest of S. Golomb) and in a slightly looser way to sequences. Correlation-immune Boolean functions (in short, CI functions) have the property of keeping the same output distribution when some input variables are fixed. They have been widely used as combiners in stream ciphers to allow resistance to the Siegenthaler correlation attack. Very recently, a new use of CI functions has appeared in the framework of side channel attacks (SCA). To reduce the cost overhead of counter-measures to SCA, CI functions need to have low Hamming weights. This actually poses new challenges since the known constructions which are based on properties of the Walsh-Hadamard transform, do not allow to build unbalanced CI functions. In this paper, we propose constructions of low-weight dth-order CI functions based on the Fourier- Hadamard transform, while the known constructions of resilient functions are based on the Walsh-Hadamard transform. We first prove a simple but powerful result, which makes that one only need to consider the case where d is odd in further research. Then we investigate how constructing low Hamming weight CI functions through the Fourier-Hadamard transform (which behaves well with respect to the multiplication of Boolean functions). We use the characterization of CI functions by the Fourier-Hadamard transform and introduce a related general construction of CI functions by multiplication. -

Indifferentiable Authenticated Encryption

Indifferentiable Authenticated Encryption Manuel Barbosa1 and Pooya Farshim2;3 1 INESC TEC and FC University of Porto, Porto, Portugal [email protected] 2 DI/ENS, CNRS, PSL University, Paris, France 3 Inria, Paris, France [email protected] Abstract. We study Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) from the viewpoint of composition in arbitrary (single-stage) environments. We use the indifferentiability framework to formalize the intuition that a \good" AEAD scheme should have random ciphertexts subject to decryptability. Within this framework, we can then apply the indifferentiability composition theorem to show that such schemes offer extra safeguards wherever the relevant security properties are not known, or cannot be predicted in advance, as in general-purpose crypto libraries and standards. We show, on the negative side, that generic composition (in many of its configurations) and well-known classical and recent schemes fail to achieve indifferentiability. On the positive side, we give a provably indifferentiable Feistel-based construction, which reduces the round complexity from at least 6, needed for blockciphers, to only 3 for encryption. This result is not too far off the theoretical optimum as we give a lower bound that rules out the indifferentiability of any construction with less than 2 rounds. Keywords. Authenticated encryption, indifferentiability, composition, Feistel, lower bound, CAESAR. 1 Introduction Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) [54,10] is a funda- mental building block in cryptographic protocols, notably those enabling secure communication over untrusted networks. The syntax, security, and constructions of AEAD have been studied in numerous works. Recent, ongoing standardization processes, such as the CAESAR competition [14] and TLS 1.3, have revived interest in this direction. -

Ohio IT Standard ITS-SEC-01 Data Encryption and Cryptography

Statewide Standard State of Ohio IT Standard Standard Number: Title: ITS-SEC-01 Data Encryption and Cryptography Effective Date: Issued By: 03/12/2021 Ervan D. Rodgers II, Assistant Director/State Chief Information Officer Office of Information Technology Ohio Department of Administrative Services Version Identifier: Published By: 2.0 Investment and Governance Division Ohio Office of Information Technology 1.0 Purpose This state IT standard defines the minimum requirements for cryptographic algorithms that are cryptographically strong and are used in security services that protect at-risk or sensitive data as defined and required by agency or State policy, standard or rule. This standard does not classify data elements; does not define the security schemes and mechanisms for devices such as tape backup systems, storage systems, mobile computers or removable media; and does not identify or approve secure transmission protocols that may be used to implement security requirements. 2.0 Scope Pursuant to Ohio Administrative Policy IT-01, “Authority of the State Chief Information Officer to Establish Ohio IT Policy,” this state IT standard is applicable to every organized body, office, or agency established by the laws of the state for the exercise of any function of state government except for those specifically exempted. 3.0 Background The National Institute for Science and Technology (NIST) conducts extensive research and development in cryptography techniques. Their publications include technical standards for data encryption, digital signature and message authentication as well as guidelines for implementing information security and managing cryptographic keys. These standards and guidelines have been mandated for use in federal agencies and adopted by state governments and private enterprises. -

Towards the Generation of a Dynamic Key-Dependent S-Box to Enhance Security

Towards the Generation of a Dynamic Key-Dependent S-Box to Enhance Security 1 Grasha Jacob, 2 Dr. A. Murugan, 3Irine Viola 1Research and Development Centre, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore – 641046, India, [email protected] [Assoc. Prof., Dept. of Computer Science, Rani Anna Govt College for Women, Tirunelveli] 2 Assoc. Prof., Dept. of Computer Science, Dr. Ambedkar Govt Arts College, Chennai, India 3Assoc. Prof., Dept. of Computer Science, Womens Christian College, Nagercoil, India E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Secure transmission of message was the concern of early men. Several techniques have been developed ever since to assure that the message is understandable only by the sender and the receiver while it would be meaningless to others. In this century, cryptography has gained much significance. This paper proposes a scheme to generate a Dynamic Key-dependent S-Box for the SubBytes Transformation used in Cryptographic Techniques. Keywords: Hamming weight, Hamming Distance, confidentiality, Dynamic Key dependent S-Box 1. INTRODUCTION Today communication networks transfer enormous volume of data. Information related to healthcare, defense and business transactions are either confidential or private and warranting security has become more and more challenging as many communication channels are arbitrated by attackers. Cryptographic techniques allow the sender and receiver to communicate secretly by transforming a plain message into meaningless form and then retransforming that back to its original form. Confidentiality is the foremost objective of cryptography. Even though cryptographic systems warrant security to sensitive information, various methods evolve every now and then like mushroom to crack and crash the cryptographic systems. NSA-approved Data Encryption Standard published in 1977 gained quick worldwide adoption. -

Cryptographic Sponge Functions

Cryptographic sponge functions Guido B1 Joan D1 Michaël P2 Gilles V A1 http://sponge.noekeon.org/ Version 0.1 1STMicroelectronics January 14, 2011 2NXP Semiconductors Cryptographic sponge functions 2 / 93 Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Roots .......................................... 7 1.2 The sponge construction ............................... 8 1.3 Sponge as a reference of security claims ...................... 8 1.4 Sponge as a design tool ................................ 9 1.5 Sponge as a versatile cryptographic primitive ................... 9 1.6 Structure of this document .............................. 10 2 Definitions 11 2.1 Conventions and notation .............................. 11 2.1.1 Bitstrings .................................... 11 2.1.2 Padding rules ................................. 11 2.1.3 Random oracles, transformations and permutations ........... 12 2.2 The sponge construction ............................... 12 2.3 The duplex construction ............................... 13 2.4 Auxiliary functions .................................. 15 2.4.1 The absorbing function and path ...................... 15 2.4.2 The squeezing function ........................... 16 2.5 Primary aacks on a sponge function ........................ 16 3 Sponge applications 19 3.1 Basic techniques .................................... 19 3.1.1 Domain separation .............................. 19 3.1.2 Keying ..................................... 20 3.1.3 State precomputation ............................ 20 3.2 Modes of use of sponge functions ......................... -

State of the Art in Lightweight Symmetric Cryptography

State of the Art in Lightweight Symmetric Cryptography Alex Biryukov1 and Léo Perrin2 1 SnT, CSC, University of Luxembourg, [email protected] 2 SnT, University of Luxembourg, [email protected] Abstract. Lightweight cryptography has been one of the “hot topics” in symmetric cryptography in the recent years. A huge number of lightweight algorithms have been published, standardized and/or used in commercial products. In this paper, we discuss the different implementation constraints that a “lightweight” algorithm is usually designed to satisfy. We also present an extensive survey of all lightweight symmetric primitives we are aware of. It covers designs from the academic community, from government agencies and proprietary algorithms which were reverse-engineered or leaked. Relevant national (nist...) and international (iso/iec...) standards are listed. We then discuss some trends we identified in the design of lightweight algorithms, namely the designers’ preference for arx-based and bitsliced-S-Box-based designs and simple key schedules. Finally, we argue that lightweight cryptography is too large a field and that it should be split into two related but distinct areas: ultra-lightweight and IoT cryptography. The former deals only with the smallest of devices for which a lower security level may be justified by the very harsh design constraints. The latter corresponds to low-power embedded processors for which the Aes and modern hash function are costly but which have to provide a high level security due to their greater connectivity. Keywords: Lightweight cryptography · Ultra-Lightweight · IoT · Internet of Things · SoK · Survey · Standards · Industry 1 Introduction The Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the foremost buzzwords in computer science and information technology at the time of writing. -

Construction of Stream Ciphers from Block Ciphers and Their Security

Sridevi, International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, Vol.3 Issue.9, September- 2014, pg. 703-714 Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IJCSMC, Vol. 3, Issue. 9, September 2014, pg.703 – 714 RESEARCH ARTICLE Construction of Stream Ciphers from Block Ciphers and their Security Sridevi, Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science, Karnatak University, Dharwad Abstract: With well-established encryption algorithms like DES or AES at hand, one could have the impression that most of the work for building a cryptosystem -for example a suite of algorithms for the transmission of encrypted data over the internet - is already done. But the task of a cipher is very specific: to encrypt or decrypt a data block of a specified length. Given an plaintext of arbitrary length, the most simple approach would be to break it down to blocks of the desired length and to use padding for the final block. Each block is encrypted separately with the same key, which results in identical ciphertext blocks for identical plaintext blocks. This is known as Electronic Code Book (ECB) mode of operation, and is not recommended in many situations because it does not hide data patterns well. Furthermore, ciphertext blocks are independent from each other, allowing an attacker to substitute, delete or replay blocks unnoticed. The feedback modes in fact turn the block cipher into a stream cipher by using the algorithm as a keystream generator. Since every mode may yield different usage and security properties, it is necessary to analyse them in detail. -

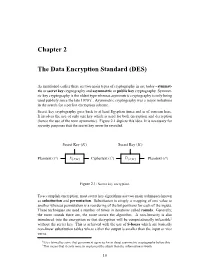

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

Security Evaluation of the K2 Stream Cipher

Security Evaluation of the K2 Stream Cipher Editors: Andrey Bogdanov, Bart Preneel, and Vincent Rijmen Contributors: Andrey Bodganov, Nicky Mouha, Gautham Sekar, Elmar Tischhauser, Deniz Toz, Kerem Varıcı, Vesselin Velichkov, and Meiqin Wang Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Department of Electrical Engineering ESAT/SCD-COSIC Interdisciplinary Institute for BroadBand Technology (IBBT) Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, bus 2446 B-3001 Leuven-Heverlee, Belgium Version 1.1 | 7 March 2011 i Security Evaluation of K2 7 March 2011 Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Linear Attacks 3 2.1 Overview . 3 2.2 Linear Relations for FSR-A and FSR-B . 3 2.3 Linear Approximation of the NLF . 5 2.4 Complexity Estimation . 5 3 Algebraic Attacks 6 4 Correlation Attacks 10 4.1 Introduction . 10 4.2 Combination Generators and Linear Complexity . 10 4.3 Description of the Correlation Attack . 11 4.4 Application of the Correlation Attack to KCipher-2 . 13 4.5 Fast Correlation Attacks . 14 5 Differential Attacks 14 5.1 Properties of Components . 14 5.1.1 Substitution . 15 5.1.2 Linear Permutation . 15 5.2 Key Ideas of the Attacks . 18 5.3 Related-Key Attacks . 19 5.4 Related-IV Attacks . 20 5.5 Related Key/IV Attacks . 21 5.6 Conclusion and Remarks . 21 6 Guess-and-Determine Attacks 25 6.1 Word-Oriented Guess-and-Determine . 25 6.2 Byte-Oriented Guess-and-Determine . 27 7 Period Considerations 28 8 Statistical Properties 29 9 Distinguishing Attacks 31 9.1 Preliminaries . 31 9.2 Mod n Cryptanalysis of Weakened KCipher-2 . 32 9.2.1 Other Reduced Versions of KCipher-2 . -

Rebound Attack

Rebound Attack Florian Mendel Institute for Applied Information Processing and Communications (IAIK) Graz University of Technology Inffeldgasse 16a, A-8010 Graz, Austria http://www.iaik.tugraz.at/ Outline 1 Motivation 2 Whirlpool Hash Function 3 Application of the Rebound Attack 4 Summary SHA-3 competition Abacus ECHO Lesamnta SHAMATA ARIRANG ECOH Luffa SHAvite-3 AURORA Edon-R LUX SIMD BLAKE EnRUPT Maraca Skein Blender ESSENCE MCSSHA-3 Spectral Hash Blue Midnight Wish FSB MD6 StreamHash Boole Fugue MeshHash SWIFFTX Cheetah Grøstl NaSHA Tangle CHI Hamsi NKS2D TIB3 CRUNCH HASH 2X Ponic Twister CubeHash JH SANDstorm Vortex DCH Keccak Sarmal WaMM Dynamic SHA Khichidi-1 Sgàil Waterfall Dynamic SHA2 LANE Shabal ZK-Crypt SHA-3 competition Abacus ECHO Lesamnta SHAMATA ARIRANG ECOH Luffa SHAvite-3 AURORA Edon-R LUX SIMD BLAKE EnRUPT Maraca Skein Blender ESSENCE MCSSHA-3 Spectral Hash Blue Midnight Wish FSB MD6 StreamHash Boole Fugue MeshHash SWIFFTX Cheetah Grøstl NaSHA Tangle CHI Hamsi NKS2D TIB3 CRUNCH HASH 2X Ponic Twister CubeHash JH SANDstorm Vortex DCH Keccak Sarmal WaMM Dynamic SHA Khichidi-1 Sgàil Waterfall Dynamic SHA2 LANE Shabal ZK-Crypt The Rebound Attack [MRST09] Tool in the differential cryptanalysis of hash functions Invented during the design of Grøstl AES-based designs allow a simple application of the idea Has been applied to a wide range of hash functions Echo, Grøstl, JH, Lane, Luffa, Maelstrom, Skein, Twister, Whirlpool, ... The Rebound Attack Ebw Ein Efw inbound outbound outbound Applies to block cipher and permutation based