1 SIMON PIERSE Alannah Coleman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

Albert Tucker: the Futile City Albert And

Albert Tucker: The Futile City 25 June to 9 October 2011 Albert and Barbara Tucker Gallery Curators: Lesley Harding and Jason Smith Albert Tucker The Futile City 1940 oil on cardboard 44.5 x 54.5 cm Heide Museum of Modern Art Purchased from John and Sunday Reed 1980 The Futile City derives its theme from Albert Robert Boynes, Louise Forthun, Richard Giblett Tucker’s iconic 1940 painting of the same title and Jeffrey Smart each use imagery of the city in Heide’s Collection. The exhibition juxtaposes as a means to examine aspects of the human images of the city painted by Tucker over his condition and the rituals of urban existence, lifetime with those by several contemporary and to suggest the place and power (or power- artists for whom the city and its structures lessness) of the individual in the city’s physical, provide rich and complex source material. political and social structures. Inspired by T.S. Eliot’s elegiac poem ‘The Waste Other artists like Susan Norrie and David Jolly Land’ (1922), which is both a lament and search invoke some of the unpredictable psychic states for redemption of the human soul, Tucker’s The to which the claustrophobia and dystopia of Futile City reflects a mood of personal despair the city give rise. Teasing out tensions between and anxiety in the face of the realities and social private and public domains, reality and fantasy, crisis of World War II. Tucker recognised in Eliot and the vulnerability and intimacy of the a ‘twin soul’ who painted with words images of body and mind, their images present stark horror, futility and prophecies of doom, to all of counterpoints to the immensity of the urban which Tucker had a heightened sensitivity. -

Robert Boynes

ROBERT BOYNES Robert Boynes is a consummate master of both technique and observation. Consisting largely of studies of the human figure located within unspecified urban environments, his work focuses on the anonymity of much contemporary social interaction. A series of dots on a wall in Fremantle was the catalyst for recent works as he continues to explore the sounds, codes and cultural bonds found in our shared spaces and streetscapes. Rather than taking a moral perspective on this condition, Robert consciously maintains a critical distance from his subjects. As a result, his images incorporate a multiplicity of references to cinema, televised news coverage and closed circuit TV footage. Robert transposes this raw material into exhilarating paintings which remind us that modernity is an amalgam of the impersonal and the intimate. Images are screened onto the surface of the canvas before acrylic paint is applied and washed back, revealing hidden forms and colours. These paintings stay with us as flashes of memory, like rapid bursts of light that resonate after the eyes are closed. Peter Haynes, art consultant, critic and former Director of the Canberra Museum and Gallery, writes of Boynes’ work: “Robert is a painter of ideas. He constantly scrutinises his world – poetry, pictures, politics, sex, the attitudes of people and the auras those people carry within themselves – in order to decipher the cryptogram that is this world. That he has found a deeply compatible visual language to give voice to his scrutinies places him at the forefront of Australian art.” Born in Adelaide, Robert studied at the South Australian School of Art in the early 1960s and began teaching in 1964. -

Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017

PenrithIan Milliss: Regional Gallery & Modernism in Sydney and InternationalThe Lewers Trends Bequest Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017 Emu Island: Modernism in Place Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 1 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction 75 Years. A celebration of life, art and exhibition This year Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest celebrates 75 years of art practice and exhibition on this site. In 1942, Gerald Lewers purchased this property to use as an occasional residence while working nearby as manager of quarrying company Farley and Lewers. A decade later, the property became the family home of Gerald and Margo Lewers and their two daughters, Darani and Tanya. It was here the family pursued their individual practices as artists and welcomed many Sydney artists, architects, writers and intellectuals. At this site in Western Sydney, modernist thinking and art practice was nurtured and flourished. Upon the passing of Margo Lewers in 1978, the daughters of Margo and Gerald Lewers sought to honour their mother’s wish that the house and garden at Emu Plains be gifted to the people of Penrith along with artworks which today form the basis of the Gallery’s collection. Received by Penrith City Council in 1980, the Neville Wran led state government supported the gift with additional funds to create a purpose built gallery on site. Opened in 1981, the gallery supports a seasonal exhibition, education and public program. Please see our website for details penrithregionalgallery.org Cover: Frank Hinder Untitled c1945 pencil on paper 24.5 x 17.2 Gift of Frank Hinder, 1983 Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 2 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction Welcome to Penrith Regional Gallery & The of ten early career artists displays the on-going Lewers Bequest Spring Exhibition Program. -

This Is Felicity Morgan Interviewing Professor Ian North on Monday, 11Th January 2010 at His Home in Adelaide About His Contribu

DON DUNSTAN FOUNDATION 1 DON DUNSTAN ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Ian NORTH This is Felicity Morgan interviewing Professor Ian North on Monday, 11th January 2010 at his home in Adelaide about his contribution to the development of the arts in South Australia during Don Dunstan’s Premiership, particularly in the field of visual arts. This recording is being made for the Don Dunstan Foundation Oral History Project and will be deposited in the Flinders University Library, Don Dunstan Special Collection, and in the State Library of South Australia. Good morning, Ian, and thank you for taking the time to do this interview. My pleasure. I wonder if we could start by you giving me a brief personal background: are you South Australian by birth and by education, and so on? No, I started my education and career in New Zealand. I was Director of what is now the Te Manawa Museum in 1969–1971 – very young, I was only twenty-four when appointed; a boy in short pants, you might say! – but from there came to the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1971 as Curator of Paintings. The position might have been called ‘Keeper of Paintings’ initially, I can’t remember. But that meant in effect all European, American and Australian paintings and sculptures. Yes, you told me that your first title was ‘Keeper of Paintings’, which was rather quaint and old-fashioned, and I wonder whether that reflected the Gallery at the time: was it also rather old-fashioned? Well, it was in many ways, as was the Adelaide art scene, although the Gallery I have to say was changing. -

Sidney Nolan's Ned Kelly

Sidney Nolan's Ned Kelly The Ned Kelly paintings in the National Gallery of Australia With essays by Murray Bail and Andrew Sayers City Gallery_JWELLINGTON australia Te \Vliare Toi ■ national gallery of 7 © National Gallery of Australia 2002 Cataloguing-in-publication data This publication accompanies the exhibition Copyright of texts remains SIDNEY NOLAN'S NED KELLY SERIES with the authors Nolan, Sidney, Sir, 1917-1992. City Gallery Wellington, New Zealand Sidney Nolan's Ned Kelly: the Ned Kelly 22 February-19 May 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication paintings in the National Gallery of Australia. Part of the New Zealand Festival 2002 may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or Bibliography. mechanical, including photocopying, ISBN O 642 54195 7. Presented by recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission 1. Kelly, Ned, 1855-1880 - Portraits - Exhibitions. in writing from the publisher. 2. Nolan, Sidney, Sir, 1917-1992 - Exhibitions. EllERNST & YOUNG 3. National Gallery of Australia - Exhibitions. Co-published by the 4. Painting, Modern - 20th century - National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Australia - Exhibitions. 5. Painting, RUSSELL M�VEAGH and City Gallery Wellington, New Zealand Australian - 20th century - Exhibitions. I. Bail, Murray, 1941- . II. Sayers, Andrew. Produced by the Publications Department III. National Gallery of Australia. IV. Title. of the National Gallery of Australia Tele�erm NEW ZEALAND Designer Kirsty Morrison 759.994 Editor Karen -

MS 65 Papers of Studio One

MS 65 Papers of Studio One Summary Administrative Information Scope and Content Biographical Note Series List and Description Box Description Folder Description Summary Creator: Studio One staff Title: Papers of Studio One Date range: 1985-2000 Reference number: MS 65 50 Boxes + 13 ring binders + 1 oversized Extent: box Administrative Information Access See National Gallery of Australia Research Library reference desk librarians. Provenance The papers were salvaged by Roger Butler, Senior Curator of Australian Prints and Drawing at the National Gallery of Australia in early 2000 after they were had been assigned for disposal. Scope and Content Series 1 of the collection comprises 42 boxes of material directly related to the administrative functions of a small, Canberra based, print editioning organisation and spans 17 years from 1985 to 2002. Within this series are 13 ring binders that contain a variety of media including negatives, photographs, slides and prints. Included in this series is an oversized box containing outsized material. Series 2 consists of financial records. The collection content includes correspondence; funding applications; board meeting agendas and minutes; reports; job cards (print editioning forms) and printing contracts, with financial records in the second series. Various artists represented in the National Gallery of Australia Collection used the Studio One editioning services. These include George Gittoes, Rosalie Gascoigne, Dennis Nona, Treahna Hamm, Jane Bradhurst, Pamela Challis, Ray Arnold, Lesbia Thorpe (Lee Baldwin) and Bruno Leti. This collection also documents, through records of correspondence, workshop details and job cards, the development of relationships with Indigenous artists through print workshops and print editioning as convened by Theo Tremblay and Basil Hall, including Melville Island, Munupi Arts and Crafts, Cairns TAFE, and Turkey Creek. -

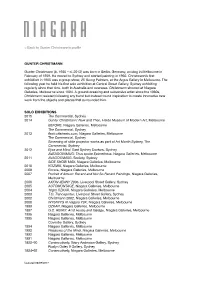

Gunter Christmann's Profile

< Back to Gunter Christmann’s profile GUNTER CHRISTMANN Gunter Christmann (b. 1936 – d. 2013) was born in Berlin, Germany, arriving in Melbourne in February of 1959. He moved to Sydney and started painting in 1962. Christmann’s first exhibition in 1965 was a group show, 25 Young Painters, at the Argus Gallery in Melbourne. The following year he held his first solo exhibition at Central Street Gallery, Sydney exhibiting regularly since that time, both in Australia and overseas. Christmann showed at Niagara Galleries, Melbourne since 1984. A ground-breaking and subversive artist since the 1960s, Christmann resisted following any trend but instead found inspiration to create innovative new work from the objects and places that surrounded him. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 The Commercial, Sydney 2014 Gunter Christmann: Now and Then, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne BEFORE, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne The Commercial, Sydney 2013 flexicuffstreets.com, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne The Commercial, Sydney Screening of slide projector works as part of Art Month Sydney, The Commercial, Sydney 2012 Eyes and Mind, East Sydney Doctors, Sydney AVEAGOYAMUG: Thus spoke Epimetheus, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2011 AVAGOYAMUG, Society, Sydney SIDE SHOW MAX, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2010 KOZMIX, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2008 Encore, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2007 Portrait d’Amour: Recent and Not So Recent Paintings, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2006 AXION JENNY 2006, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney 2005 AUTOMONTAGE, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2004 10gm OZKAR, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2003 T.O. Tranceporter, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney 2002 Christmann 2002, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 2000 WYSIWYG @ niagara Y2K, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 1999 OZKAR, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne 1997 G.C. -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

Gunter Christmann (B

It is with great pleasure that The Commercial presents its third solo exhibition by Gunter Christmann (b. 1936, Berlin, d. 2013, Sydney). The exhibition comprises a group of late paintings alongside a group of small works on paper from 1975-77. The two bodies of work, created four decades apart, are linked by a common process: Christmann’s idiosyncratic shuffle box or water tank technique, simple devices for the creation of composition in painting. In addition to providing a system that allowed the universe to determine the arrangement of objects for the artist to paint, the small shuffle boxes, proportioned the same as the intended painting, perfectly housed the humble items -- bottle tops, cable ties, leaves, etc. -- offered up by the streets around the artist’s Darlinghurst home, urban refuse insignificant until incorporated into the body of the painting, its still life. The pull of gravity dictated Christmann’s technique involving the arrangement and rearrangement of small, street-scavenged things. This ground-consciousness developed out of the ‘sprankle’ paintings of the late 1960s/early 1970s in which paint was dropped onto the canvas on the ground from standing height ‘like rain’, such as the wonderful Over Orange (c. 1969) and Oktoberwald (1973) currently on display at the Art Gallery of Western Australia and Art Gallery of New South Wales respectively as part of those institutions’ permanent collections. Returning to his shuffle boxes in later years, as part of the general humility and self-sufficiency of Christmann’s studio practice, the group of paintings in the forthcoming exhibition are characterized by their sponged grounds, optically similar in their blending of colour to the early sprankle paintings though achieved through the compression of space between passive canvas and deliberate hand. -

228 Paddington: a History

228 Paddington: A history Paddington_Chapter9_Final.indd 228 23/9/18 2:37 pm Chapter 9 Creative Paddington Peter McNeil 22 9 229 Paddington_Chapter9_Final.indd 229 23/9/18 2:37 pm Margaret Olley, one of Australia’s favourite artists, The creatives of Paddington today are more likely died in July 2011. She had become synonymous to run an art space, architecture or design firm, with the suburb of Paddington. As if to celebrate engage in public relations and media, trade her art and personal energy, her estate left the commodities, or be retired doctors or lawyers. downstairs lights of her home blazing, revealing the In the Paddington–Moore Park area today, nearly bright walls as well as her own artworks, including 20 per cent of employees work in legal and rooms she made famous by including them as financial services.3 subjects. Olley loved the suburb of Paddington. But why have so many culturally influential She could paint, garden and, entertain there from people lived in Paddington? Located conveniently her large corner terrace in Duxford Street. She close to the central business district which could liked the art crowd as well as the young people be reached by bus, tram and later the train link working in shops and the working-class people at Edgecliff station, its mixture of terraced who still lived there. She recalled that, as art houses, small factories, workshops and students at the old Darlinghurst Gaol in the early warehouses, provided cultural producers – 1940s, ‘Paddington beckoned … we knew there was whether they be artists or advertising executives something across beyond the Cutler Footway, but – a range of multi-functional spaces and initially we dared not go there’.1 Within a generation interpersonal networks. -

Chapter 4. Australian Art at Auction: the 1960S Market

Pedigree and Panache a history of the art auction in australia Pedigree and Panache a history of the art auction in australia Shireen huda Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/pedigree_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Author: Huda, Shireen Amber. Title: Pedigree and panache : a history of the art auction in Australia / Shireen Huda. ISBN: 9781921313714 (pbk.) 9781921313721 (web) Notes: Includes index. Bibliography. Subjects: Art auctions--Australia--History. Art--Collectors and collecting--Australia. Art--Prices--Australia. Dewey Number: 702.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: John Webber, A Portrait of Captain James Cook RN, 1782, oil on canvas, 114.3 x 89.7 cm, Collection: National Portrait Gallery, Canberra. Purchased by the Commonwealth Government with the generous assistance of Robert Oatley and John Schaeffer 2000. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements