The Pursuit of Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judges' Annual Report

Supreme Court of Victoria 2002–04 Annual Report SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA 2002–04 JUDGES’ ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS LETTER TO THE GOVERNOR Court Profile 1 To His Excellency Year at a Glance 2 The Honourable John Landy, AC, MBE Report of the Chief Justice 3 Governor of the State of Victoria and its Chief Executive Officer’s Review 7 Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia Court of Appeal 10 Dear Governor Trial Division: Civil 13 We, the Judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria have the honour to present our Annual Report Trial Division: Commercial and Equity 18 pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial years of Trial Division: Common Law 22 1 July 2002 to 30 June 2003 and 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2004, including a transitional 18-month Trial Division: Criminal 24 Judges’ Report, reflecting the change in reporting period from calendar year to financial year. Masters 26 Funds in Court 29 Court Governance 31 Yours sincerely Judicial Organisational Chart 33 Judicial Administration 34 Court Management 36 Service Delivery 37 The Victorian Jury System 40 Marilyn L Warren The Court’s People 42 Chief Justice of Victoria Community Access 43 10 May 2005 Finance Report 2002–03 and 2003–04 45 Senior Master’s Special Purpose Financial Report for the John Winneke, P P D Cummins, J D J Habersberger, J Year Ended 30 June 2003 50 W F Ormiston, J A T H Smith, J R S Osborn, J Senior Master’s Special Purpose Stephen Charles, J A David Ashley, J J A Dodds-Streeton, J Financial Report for the F H Callaway, J A John -

A 'Common-Sense Revolution'? the Transformation of the Melbourne City

A ‘COMMON-SENSE REVOLUTION’? THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE MELBOURNE CITY COUNCIL, 1992−9 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April, 2015 Angela G. Munro Faculty of Business, Government and Law Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is the culmination of almost fifty years’ interest professionally and as a citizen in local government. Like many Australians, I suspect, I had barely noticed it until I lived in England where I realised what unique attributes it offered, despite the different constitutional arrangements of which it was part. The research question of how the disempowerment and de-democratisation of the Melbourne City Council from 1992−9 was possible was a question with which I had wrestled, in practice, as a citizen during those years. My academic interest was piqued by the Mayor of Stockholm to whom I spoke on November 18, 1993, the day on which the Melbourne City Council was sacked. ‘That couldn’t happen here’, he said. I have found the project a herculean labour, since I recognised the need to go back to 1842 to track the institutional genealogy of the City Council’s development in the pre- history period to 1992 rather than a forensic examination of the seven year study period. I have been exceptionally fortunate to have been supervised by John Halligan, Professor of Public Administration at University of Canberra. An international authority in the field, Professor Halligan has published extensively on Australian systems of government including the capital cities and the Melbourne City Council in particular. -

Letter from Melbourne Is a Monthly Public Affairs Bulletin, a Simple Précis, Distilling and Interpreting Mother Nature

SavingLETTER you time. A monthly newsletter distilling FROM public policy and government decisionsMELBOURNE which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. p11-14: Special Melbourne Opera insert Issue 161 Our New Year Edition 16 December 2010 to 13 January 2011 INSIDE Auditing the state’s affairs Auditor (VAGO) also busy Child care and mental health focus Human rights changes Labor leader no socialist. Myki musings. Decision imminent. Comrie leads Victorian floods Federal health challenge/changes And other big (regional) rail inquiry HealthSmart also in the news challenge Baillieu team appointments New water minister busy Windsor still in the news 16 DECEMBER 2010 to 13 JANUARY 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our government warming up. P 03 9654 1300 Even some supporters of the Baillieu government have commented that it is getting off to a slow F 03 9654 1165 start. The fact is that all ministers need a chief of staff and specialist and other advisers in order to [email protected] properly interface with the civil service, as they apply their new policies and different administration www.letterfromcanberra.com.au emphases. These folk have to come from somewhere and the better they are, the longer it can take for them to leave their current employment wherever that might be and settle down into a government office in Melbourne. Editor Alistair Urquhart Some stakeholders in various industries are becoming frustrated, finding it difficult to get the Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson interaction they need with a relevant minister. -

Knight V Commonwealth of Australia (No 3)

SUPREME COURT OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Case Title: Knight v Commonwealth of Australia (No 3) Citation: [2017] ACTSC 3 Hearing Dates: 4, 7 May, 3 August, 3 November 2015 Decision Date: 13 January 2017 Before: Mossop AsJ Decision: See [233] Catchwords: LIMITATION OF ACTIONS – Application for extension of time – Claim for damages arising out of assault and negligence – Multiple incidents giving rise to claims – Incidents occurred while plaintiff was a cadet at the Royal Military College, Duntroon – Plaintiff subsequently sentenced and imprisoned for separate incident – 27-year delay in commencing proceedings – Whether Limitation Act 1985 (ACT) s 36 permitting the grant of an extension of time applies – Whether an explanation for the delay existed – Whether just and reasonable to grant extension of time – Consideration s 36(3) considerations – Meaning of disability for the purposes of s 36(3)(d) – Broader significance in relation to abuse in the armed services – Significance of absence of other remedies – Proportionality between damages and cost and effort associated with running claim – Whether proceedings amount to abuse of process – Whether use of proceedings as a means of achieving an interstate transfer predominant purpose of bringing proceedings – application dismissed Legislation Cited: Civil Law (Wrongs) Amendment 2003 (No 2) (ACT), s 58 Corrections Act 1986 (Vic), s 74AA Corrections Amendment (Parole) Act 2014 (Vic) Crimes (Sentence Administration) Act 2005 (ACT), s 244 Interpretation of Legislation Act 1984 (Vic) Legislation -

Penal and Prison Discipline

1871. VICTORIA. REPORT (No.2) OF THE ROYAL COMMISSION ON PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF l'AULIAMENT BI HIS EXCELLENCY'S COMMAND. lS!! autf}ont!!: JOHN FERRES, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, lllELllOURNE, No. 31. .... TABLE OF CONTENTS. I. REPOR'l': l. Punishment Sec. I to 8 2. Discretionary Power of Judges 9 to IS 3. Habitual Criminals ... 19 to 20 4. Remission of Sentences 21 to 27 5. Vfe Sentences 28 to 30 6. Miscellaneous Offences 31 to 34 7. Juvenile Offenders ••• 35 to 40 8. The Crofton System .•• 41 to 49 9. Gaols 50 to 58 10. .Adaptation of Crofton System 59 to 64 II. Board of Honorary Visitors 65 to 69 12. Conclusion ... 70 to 71 2 . .APPENDICES 'l'O REPORT : J. lion. J.D. Wood's Report on Irish Prisons Page xxiii 2. Circular to Sheriffs ... xxix 3. Summary of Replies to Circular XXX 3. EVIDENCE 4 • .APPENDICES 'l'O EviDENCE 28 Al',PROXBIATE COST OF JU:l'OHT. Preparation-Not g·iven. £ •. d. hhvrthand "\Vriting, &e. (Attendances, £23 2s.; TJ anscript~ BOO foHos, £40) 6:l 2 0 l::rlut.tng {850 copies) 59 0 0 122 2 () ROYAL CO~IMISSION ON PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. REPORT (No. 2) ON PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. \VE, the undersigned Commissioners, appointed under Letters Patent from the Crown, bearing date the 8th day of August 1870, to enquire into and report upon the Condition of the Penal and Prison Esta.blish ments and Penal Discipline in Victoria, have the honor to submit to Your Excellency the following further Report:- I.-PUNISHMENT. -

Qatar, France Sign Pact for Strategic Dialogue

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Czech star Pliskova takes tough Vodafone Qatar schedule in posts QR118mn profi t in 2018 her stride published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11092 February 12, 2019 Jumada II 7, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets French FM Amir honours winners of state awards His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani honoured winners of the Qatar’s appreciative and incentive state awards in sciences, arts and literature. His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met with French Minister The award winners were Dr Abdulaziz bin Abdullah Turki al-Subaie in the field of education, Mohamed Jassim al-Khulaifi (museums and archaeology), Dr Saif Saeed of Europe and Foreign Aff airs Jean-Yves Le Drian and his accompanying delegation Saif al-Suwaidi (economics), Dr Yousif Mohamed Yousif al-Obaidan (political science), Dr Hamad Abdulrahman al-Saad al-Kuwari (earth and environmental sciences), at the Amiri Diwan yesterday. The minister conveyed to the Amir the congratulations Mohanna Rashid al-Asiri al-Maadeed (earth and environmental sciences), Dr Huda Mohamed Abdullatif al-Nuaimi (allied medical sciences and nursing), Dr Asma of French President Emmanuel Macron on Qatar national football team winning the Ali Jassim al-Thani (allied medical sciences and nursing), Salman Ibrahim Sulaiman al-Malik (the art of caricature) and Abdulaziz Ibrahim al-Mahmoud in the novel 2019 Asian Cup. During the meeting, they reviewed bilateral relations and means of field. The Amir commended the winners’ distinguished performance, wishing them success in rendering services to the homeland. -

Crime and Criminals;

CRIME AND CRIMINALS; OR, . t .* REMINISCENCES OF THE PENAL DEPARTMENT IN VICTORIA. HENRY A. WHITE, SECOND OFFICER OF THE BALLARAT GAOL. $allanit : Berry? Anderson & Co., Printers, 20, 22, and 24 Ly diaid Street South M'DCCCXC. all lights reserved. BEERY, ANDERSON & CO., PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS, BALLARAT 430200 To Colonel William Thomas Napier Champ (Late Inspector-General of Penal Establishments in Victoria) Whose Impartial Administration of THE Penal Department Stands Unrivalled, These Reminiscences of a Warder’s Life Are Most Respectfully and Gratefully Dedicated by the Author. PREFACE. The author of this work has not resolved to launch his little craft on the great sea of literature without feeling that the winds and waves might handle her very roughly, but he trusts to the generosity of the public. His only qualifications for so difficult and important a task as that of recording 30 years of the history of penal establish ments are intimate knowledge as a subordinate officer of its details, and an honest desire to state impartially what he believes to be of interest to the public, and of undoubted fact. The accumulation of the materials of this work, involving much research into documents of the past, has occupied his leisure hours for many years, and as life is short and the present seems to be a time when there is no burning question before the public respecting the treatment of criminals, he deems it best to delay no longer its publication. He trusts that those who differ from his opinions as here expressed will yet overlook any imperfections in his style of narration, and that all his readers may have as much pleasure in reading these pages as he has had in compiling them. -

Year in Review 2018/2019

Contents Shaping the Museum of the Future 2 Philanthropy on View 4 The Year at a Glance 8 Compelling Mix of Original and Touring Exhibitions 12 ROM Objects on Loan Locally and Globally 26 Leading-Edge Research 36 ROM Scholarship in Print 46 Community Connections 50 Access to First Peoples Art and Culture 58 Programming That Inspires 60 Learning at the ROM 66 Members and Volunteers 70 Digital Readiness 72 Philanthropy 74 ROM Leadership 80 Our Supporters 86 2 royal ontario museum year in review 2018–2019 3 One of the initiatives we were most proud of in 2018 was the opening of the Daphne Cockwell Gallery dedicated to First Peoples art & culture as free to the public every day the Museum is open. Initiatives such as this represent just one step on our journey. ROM programs and exhibitions continue to be bold, ambitious, and diverse, fostering discourse at home and around the world. Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world, Gods in My Home: Chinese New Year with Ancestor Portraits and Deity Prints and The Evidence Room helped ROM visitors connect past to present and understand forces and influences that have shaped our world, while #MeToo & the Arts brought forward a critical conversation about the arts, institutions, and cultural movements. Immersive and interactive exhibitions such as aptured in these pages is a pivotal Zuul: Life of an Armoured Dinosaur and Spiders: year for the Royal Ontario Museum. Fear & Fascination showcased groundbreaking Shaping Not only did the Museum’s robust ROM research and world-class storytelling. The Cattendance of 1.34 million visitors contribute to success achieved with these exhibitions set the our ranking as the #1 most-visited museum in stage for upcoming ROM-originals Bloodsuckers: the Canada and #7 in North America according to The Legends to Leeches, The Cloth That Changed the Art Newspaper, but a new report by Deloitte shows World: India’s Painted and Printed Cottons, and the the ROM, through its various activities, contributed busy slate of art, culture, and nature ahead. -

Annual Report the Hon

2009–10 annual report The Hon . Rob Hulls, MP Attorney-General 55 St Andrews Place Melbourne Victoria 3002 Dear Attorney-General I am pleased to present to you a report in accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994 and Section 62 of the Information Privacy Act 2000, for the year ending 30 June 2010, for presentation to Parliament . Yours sincerely HELEN VERSEY Privacy Commissioner August 2010 COVER IMAGES: TOP Left: Privacy Commissioner Helen Versey with Tjimba possum-Burns and Danny Ramzan from The Yung Warriors at the Watch this space conference, May 2010 TOP RIGHT: Noni Hazlehurst with members of Privacy Victoria’s Youth Advisory Group at the Watch this space conference Bottom Left: Year 9 students from CBC Ordered to be printed St Kilda at the Watch this space conference Victorian Government Printer 2010 Bottom RIGHT: The Privacy Victoria and PP 320, Session 2006-10 Office of the Health Service Commissioner display at the 2009 Royal Melbourne show Editor David Taylor Cover photography Heather Venn 1 contents Office of the commissioner’s overview . 2 report on the operations of the office . 4 Victorian Privacy Commissioner functions of the office . 5 Advise and Guide . 5 Audit and Monitor . 13 Handle Complaints . 13 Handle Enquiries . 21 Investigate and Enforce . 26 2009–10 2009–10 Liaise and Co-operate . 28 Promote Awareness . 32 annual report Research and Report . 42 managing our office . 43 financial report . 50 Comprehensive Operating Statement . 50 Balance Sheet . 51 Statement of Changes in Equity . 52 Cash Flow Statement . 53 Notes to the Financial Statements . 54 Accountable Officer’s and Chief Financial and Accounting Officer’s Declaration . -

Part 5. the Battle of Bet Bet 1986-1988

The New Dissenters The Renewal of Victorian Goldfields Agitation in the 20th Century Part Five The Battle of Bet Bet 1986-1988 The Battle of Bet Bet was about a local government placing a whole new layer of approvals and bonds on Miner’s Right Claims and Leases. It also tried to introduce a set of heritage overlays they effectively shut down the shire in respect of mining. It culminated a period of intense anti-mining ideology. Prior, in the years 1986 and 1987 there was a near unbelievable continuous inflow of argument and expectations about mining law, rights and amendments. This included intense activity from land protection groups and the government with its rapidly multiplying departments. The only people who did not go on the anti-mining attack were the small-scale gold miners, who found themselves continuously on the defensive against further restrictions and losses. Underlying and disguised by all of this chaos and regulatory tinkering was a new threat which appeared to be simply another review of mining. Stephen Barnham Copyright Stephen Barnham 2011 The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work, and owner of this intellectual property. DEDICATION To the previously unrecognised people who worked so hard to try and protect Victoria’s gold prospecting and small-scale gold mining heritage and those who realise the importance of understanding your own history. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS John’s wife Nola Winter who had the foresight not to throw out numerous documents when John Winter died. Anne Doran who carefully saved mining related Central Victorian newspaper articles and typed many letters for Frank Kopacka. -

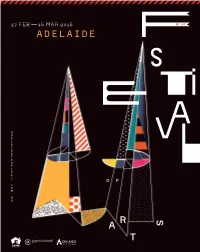

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

Fat Tony__Co Final D

A SCREENTIME production for the NINE NETWORK Production Notes Des Monaghan, Greg Haddrick Jo Rooney & Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler, Adam Todd, Jeff Truman & Michaeley O’Brien SERIES WRITERS Peter Andrikidis, Andrew Prowse & Karl Zwicky SERIES DIRECTORS MEDIA ENQUIRIES Michelle Stamper: NINE NETWORK T: 61 3 9420 3455 M: 61 (0)413 117 711 E: [email protected] IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTIFICATION TO MEDIA Screentime would like to remind anyone reporting on/reviewing the mini-series entitled FAT TONY & CO. that, given its subject matter, the series is complicated from a legal perspective. Potential legal issues include defamation, contempt of court and witness protection/name suppression. Accordingly there are some matters/questions that you may raise which we shall not be in a position to answer. In any event, please note that it is your responsibility to take into consideration all such legal issues in determining what is appropriate for you/the company who employs you (the “Company”) to publish or broadcast. Table of Contents Synopsis…………………………………………..………..……………………....Page 3 Key Players………….…………..…………………….…….…..……….....Pages 4 to 6 Production Facts…………………..…………………..………................Pages 7 to 8 About Screentime……………..…………………..…….………………………Page 9 Select Production & Cast Interviews……………………….…….…Pages 10 to 42 Key Crew Biographies……………………………………………...….Pages 43 to 51 Principal & Select Supporting Cast List..………………………………...….Page 52 Select Cast Biographies…………………………………………….....Pages 53 to 69 Episode Synopses………………………….………………….………..Pages 70 to 72 © 2013 Screentime Pty Ltd and Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd 2 SYNOPSIS FAT TONY & CO., the brand-new production from Screentime, tells the story of Australia’s most successful drug baron, from the day he quit cooking pizza in favour of cooking drugs, to the heyday of his $140 million dollar drug empire, all the way through to his arrest in an Athens café and his whopping 22-year sentence in Victoria’s maximum security prison.