* Text Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past CB Pitching Coaches of Year

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 62, No. 1 Friday, Jan. 4, 2019 $4.00 Mike Martin Has Seen It All As A Coach Bus driver dies of heart attack Yastrzemski in the ninth for the game winner. Florida State ultimately went 51-12 during the as team bus was traveling on a 1980 season as the Seminoles won 18 of their next 7-lane highway next to ocean in 19 games after those two losses at Miami. San Francisco, plus other tales. Martin led Florida State to 50 or more wins 12 consecutive years to start his head coaching career. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Entering the 2019 season, he has a 1,987-713-4 Editor/Collegiate Baseball overall record. Martin has the best winning percentage among ALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Mike Martin, the active head baseball coaches, sporting a .736 mark winningest head coach in college baseball to go along with 16 trips to the College World Series history, will cap a remarkable 40-year and 39 consecutive regional appearances. T Of the 3,981 baseball games played in FSU coaching career in 2019 at Florida St. University. He only needs 13 more victories to be the first history, Martin has been involved in 3,088 of those college coach in any sport to collect 2,000 wins. in some capacity as a player or coach. What many people don’t realize is that he started He has been on the field or in the dugout for 2,271 his head coaching career with two straight losses at of the Seminoles’ 2,887 all-time victories. -

Oakland Athletics Baseball Company7000 Coliseum Wayoakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 PR on Twitter @Asmedia Alerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (11-17-3) VS

O AKLAND A THLETICS Game Information Oakland Athletics Baseball Company7000 Coliseum WayOakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900www.athletics.comA’s PR on Twitter @AsMedia Alerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (11-17-3) VS. SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (13-19-1) SATURDAY, APRIL 2, 2016 – OAKLAND ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM – 1:05 P.M. PST CSNCA – A’S RADIO NETWORK (95.7 FM THE GAME) ABOUT THE A’S: Have lost five straight and eight of the last nine games… for the lead in runs (11)…has appeared in 14 games in left field and three this is the A’s longest Spring Training losing streak since dropping the final in right field…Jed Lowrie is 7-for-18 (.389) over his last seven games six games of 2011…are 11-17-3, which is the third worst record among and is batting .395 overall…nine of his last 12 hits are for extra bases Cactus League teams (San Diego, 10-20-2; Chicago-NL, 11-18-2)…will (seven doubles, one triple, one home run)…leads the A’s and is tied for finish with a losing record for the first time since 2011 when they went fifth in the CL in doubles (7)…is tied for the team lead in slugging (.674)… 12-21-1…the A’s have committed 44 errors, which is seven more than any has appeared in 15 games at second base and two at shortstop…Bruce other team (37, Chicago-NL)…the errors are the most by an A’s team dur- Maxwell (NR) is 2-for-11 (.182) with a home run and two RBI in 10 games ing the spring since the 2002 club also had 44…the A’s pitching staff is tied since returning from playing for Germany in the World Baseball Classic with Boston for the most walks (123)…have matched -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, March 3, 2021 * The Boston Globe How Nick Pivetta is embracing a fresh start with the Red Sox Peter Abraham FORT MYERS, Fla. — Nick and Kristen Pivetta have been nomads for some time, unable to return to their native Canada because of strict pandemic protocols regarding crossing the border from the United States. “We haven’t been home in almost two years,” said Nick, a righthander who was traded to the Red Sox last summer. “So we packed up and came here.” Home is now a rented condo a short drive from JetBlue Park. They arrived in October for what in every way has been a fresh start. Pivetta, 28, spent nearly five years with the Philadelphia Phillies. He made his major league debut with the team in 2017, won his first game a few weeks later, and struck out 13 Cardinals one memorable night in 2018. But he welcomed the trade to Boston. It was time. “I can’t speak on behalf of the Phillies. But I don’t feel they valued me as a starter anymore,” Pivetta said. “I was ready for some new scenery. It was best for both parties.” That was easily confirmed, a Phillies official saying the team felt Pivetta was more confident in his abilities than a career 5.40 earned run average suggested he should be. They recognized his talent but were frustrated by his stubbornness. The Red Sox took a chance on the talent, trading relievers Heath Hembree and Brandon Workman for Pivetta and righthander Connor Seabold. -

2020 Topps Chrome Sapphire Edition .Xls

SERIES 1 1 Mike Trout Angels® 2 Gerrit Cole Houston Astros® 3 Nicky Lopez Kansas City Royals® 4 Robinson Cano New York Mets® 5 JaCoby Jones Detroit Tigers® 6 Juan Soto Washington Nationals® 7 Aaron Judge New York Yankees® 8 Jonathan Villar Baltimore Orioles® 9 Trent Grisham San Diego Padres™ Rookie 10 Austin Meadows Tampa Bay Rays™ 11 Anthony Rendon Washington Nationals® 12 Sam Hilliard Colorado Rockies™ Rookie 13 Miles Mikolas St. Louis Cardinals® 14 Anthony Rendon Angels® 15 San Diego Padres™ 16 Gleyber Torres New York Yankees® 17 Franmil Reyes Cleveland Indians® 18 Minnesota Twins® 19 Angels® Angels® 20 Aristides Aquino Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 21 Shane Greene Atlanta Braves™ 22 Emilio Pagan Tampa Bay Rays™ 23 Christin Stewart Detroit Tigers® 24 Kenley Jansen Los Angeles Dodgers® 25 Kirby Yates San Diego Padres™ 26 Kyle Hendricks Chicago Cubs® 27 Milwaukee Brewers™ Milwaukee Brewers™ 28 Tim Anderson Chicago White Sox® 29 Starlin Castro Washington Nationals® 30 Josh VanMeter Cincinnati Reds® 31 American League™ 32 Brandon Woodruff Milwaukee Brewers™ 33 Houston Astros® Houston Astros® 34 Ian Kinsler San Diego Padres™ 35 Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® 36 Sean Doolittle Washington Nationals® 37 Albert Almora Chicago Cubs® 38 Austin Nola Seattle Mariners™ Rookie 39 Tyler O'neill St. Louis Cardinals® 40 Bobby Bradley Cleveland Indians® Rookie 41 Brian Anderson Miami Marlins® 42 Lewis Brinson Miami Marlins® 43 Leury Garcia Chicago White Sox® 44 Tommy Edman St. Louis Cardinals® 45 Mitch Haniger Seattle Mariners™ 46 Gary Sanchez New York Yankees® 47 Dansby Swanson Atlanta Braves™ 48 Jeff McNeil New York Mets® 49 Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® Rookie 50 Cody Bellinger Los Angeles Dodgers® 51 Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® 52 Yasmani Grandal Chicago White Sox® 53 Pete Alonso New York Mets® 54 Hunter Dozier Kansas City Royals® 55 Jose Martinez St. -

2013 Professional Baseball Trading Cards

HOBBY 2013 PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL TRADING CARDS Panini America, Inc. is in no way affiliated with either Major League Baseball or Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. nor have these trading cards been prepared, approved, endorsed, or licensed by either Major League Baseball or Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. © 2013 Panini America, Inc. Printed in the USA. © 2013 MLBPA. Official Licensee -- Major League Baseball Players Association 2013 PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL TRADING CARDS HOBBY Bat Knob Cards Yasiel Puig exploded onto the big-league scene in May, and over the next four months became the talk of baseball. Swatches from two of the first bats Puig used in the majors can be found in America's Pastime as well as these 1/1 beauties! NATIONAL TREASURES ROOKIE ROOKIE BOOKLETS Panini America, Inc. is in no way affiliated with either Major League Baseball or Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. nor have these trading cards been prepared, approved, endorsed, or licensed by either Major League Baseball or Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. © 2013 Panini America, Inc. Printed in the USA. © 2013 MLBPA. Official Licensee -- Major League Baseball Players Association 2013 PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL TRADING CARDS HOBBY BETWEEN THE SEAMS Look for baseball material signatures from a list that includes Mariano Rivera, Stan Musial, Ken Griffey Jr., Yogi Berra, Ernie Banks, Matt Kemp, Dustin Pedroia, and Tom Seaver among others! NATIONAL TREASURES ROOKIE ROOKIE BOOKLETS Panini America, Inc. is in no way affiliated with either Major League Baseball or Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. nor have these trading cards been prepared, approved, endorsed, or licensed by either Major League Baseball or Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. -

Red Sox Vs. Rays: Target Boston to Triumph in Low- Scoring Affair

Red Sox vs. Rays: Target Boston to Triumph in Low- Scoring Affair Red Sox Odds +150 Rays Odds -170 Over/Under 8.5 (-115 / -105) Time 7:08 p.m. ET TV ESPN Odds as of Sunday afternoon via DraftKings. The Tampa Bay Rays (63-42) are looking for a home sweep and to extend their half-game lead in the AL East against the Boston Red Sox (63-43) on Sunday Night Baseball. The season series is currently tied at four games apiece, with the results over the final 11 meetings this season between these two clubs potentially determining the division winner. I currently project the Rays to win 95.4 games and the Red Sox to finish with 92.9 wins. I give Tampa Bay a 50% chance of winning the AL East and Boston a 33% chance.PECOTA ‘s projection aligns with my own, putting Tampa Bay 0.8 wins clear of Boston for the AL East crown, with respective chances of 37.1% and 34.1% to win the division. Fangraphs is higher on Boston’s chances, placing it 1.3 games ahead of Tampa Bay (94.1 wins to 93.1) with a 40.1% chance of winning the division, compared to 34.2% for the Rays. In terms of True Talent, I would make the Rays a 91.9 win team if the season restarted tomorrow and would place Boston at 86.4 wins, which is up from projections of 86.5 and 80.8 wins in the preseason. That’s an increase of 5.4 and 5.6 wins, respectively. -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

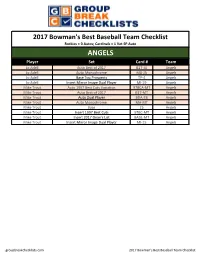

2017 Bowmans Best Baseball Group Break Checklist

2017 Bowman's Best Baseball Team Checklist Rockies = 0 Autos; Cardinals = 1 Vet SP Auto ANGELS Player Set Card # Team Jo Adell Auto Best of 2017 B17-JA Angels Jo Adell Auto Monochrome MA-JA Angels Jo Adell Base Top Prospects TP-4 Angels Jo Adell Insert Mirror Image Dual Player MI-19 Angels Mike Trout Auto 1997 Best Cuts Variation 97BCA-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto Best of 2017 B17-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto Dual Player BDA-TB Angels Mike Trout Auto Monochrome MA-MT Angels Mike Trout Base 25 Angels Mike Trout Insert 1997 Best Cuts 97BC-MT Angels Mike Trout Insert 2017 Dean's List BADL-MT Angels Mike Trout Insert Mirror Image Dual Player MI-15 Angels groupbreakchecklists.com 2017 Bowman's Best Baseball Team Checklist ASTROS Player Set Card # Team Alex Bregman Auto Best of 2017 B17-AB Astros Alex Bregman Auto Dual Player BDA-CB Astros Alex Bregman Auto Monochrome MA-ABR Astros Alex Bregman Base Rookie 54 Astros Alex Bregman Insert 1997 Best Cuts 97BC-AB Astros Alex Bregman Insert Raking Rookies RR-AB Astros Carlos Correa Auto 1997 Best Cuts Variation 97BCA-CC Astros Carlos Correa Auto Best of 2017 B17-CC Astros Carlos Correa Auto Dual Player BDA-CB Astros Carlos Correa Base 48 Astros Carlos Correa Insert 1997 Best Cuts 97BC-CC Astros Carlos Correa Insert Mirror Image Dual Player MI-20 Astros Derek Fisher Auto Best of 2017 B17-DF Astros George Springer Base 56 Astros Jeff Bagwell Auto 1997 Best Cuts Variation 97BCA-JB Astros Jeff Bagwell Insert 1997 Best Cuts 97BC-JB Astros Jose Altuve Base 9 Astros Kyle Tucker Base Top Prospects TP-23 Astros -

Boston Red Sox (82-57) Vs

BOSTON RED SOX (82-57) VS. DETROIT TIGERS (81-57) Tuesday, September 3, 2013 • 7:10 p.m. ET • Fenway Park, Boston, MA LHP Jon Lester (12-8, 3.99) vs. RHP Max Scherzer (19-1, 2.90) Game #140 • Home Game #71 • TV: NESN/MLBN • Radio: WEEI 93.7 FM, WUFC 1510 AM (Spanish) STANDING TALL: Boston plays the 2nd of 3 games LESTER’S LAST 5: Tonight’s starter Jon Lester has quality against the Tigers tonight in the 3rd and fi nal series of a starts in his last 5 outings since 8/8...In that time, he ranks RED SOX RECORD BREAKDOWN Overall ........................................... 82-57 9-game homestand...The Sox are 5-2 thus far on the stand, 3rd in the AL in ERA (tied, 1.80) and opponent AVG (.198). AL East Standing ....................1st, 5.5 GA after taking 2 of 3 from Baltimore, sweeping the White Sox At Home ......................................... 45-25 in 3 games, and dropping last night’s series opener. PEN STRENGTH: The Red Sox bullpen has been charged On Road ......................................... 37-32 On the homestand, the Sox are outscoring opponents with runs in just 1 of 7 games during the current homes- In day games .................................. 25-13 37-22 with a .286 batting average and a 3.14 ERA. tand...In that time, Sox relievers have allowed just 2 runs In night games ............................... 57-44 and 8 hits over 18.2 innings (0.96 ERA). April ................................................. 18-8 Boston’s weekend sweep of the White Sox was the May ................................................ 15-15 club’s 1st sweep since 7/30-8/1 vs. -

2021 SWB Railriders Media Guide

2021 swb railriders 2021 swb railriders triple-a information On February 12, 2021, Major League Baseball announced its new plan for affiliated baseball, with 120 Minor League clubs officially agreeing to join the new Professional Development League (PDL). In total, the new player development system includes 179 teams across 17 leagues in 43 states and four provinces. Including the AZL and GCL, there are 209 teams across 19 leagues in 44 states and four provinces. That includes the 150 teams in the PDL and AZL/GCL along with the four partner leagues: the American Association, Atlantic League, Frontier League and Pioneer League. The long-time Triple-A structure of the International and Pacific Coast Leagues have been replaced by Triple-A East and Triple-A West. Triple-A East consists on 20 teams; all 14 from the International League, plus teams moving from the Pacific Coast League, the Southern League and the independent Atlantic League. Triple-A West is comprised of nine Pacific Coast League teams and one addition from the Atlantic League. These changes were made to help reduce travel and allow Major League teams to have their affiliates, in most cases, within 200 miles of the parent club (or play at their Spring Training facilities). triple-a clubs & affiliates midwest northeast southeast e Columbus (Cleveland Indians) Buffalo (Toronto Blue Jays) Charlotte (Chicago White Sox) Indianapolis (Pittsburgh Pirates) Lehigh Valley (Philadelphia Phillies) Durham (Tampa Bay Rays) a Iowa (Chicago Cubs) Rochester (Washington Nationals) Gwinnett (Atlanta Braves) s Louisville (Cincinnati Reds) Scranton/ Wilkes-Barre (New York Yankees) Jacksonville (Miami Marlins) Omaha (Kansas City Royals) Syracuse (New York Mets) Memphis (St. -

04-02-2018 Rangers Game Notes

Texas Rangers (1-3) at Oakland Athletics (1-3) RHP Bartolo Colon (0-0, —) vs. RHP Andrew Triggs (0-0, —) Game #5 • Road #1 (0-0) • Mon., April 2, 2018 • Oakland Coliseum • 9:05 p.m. (CDT) • FSSW / 105.3 FM / 1270 AM RANGERS AT A GLANCE WINS AND LOSSES: Texas has gone 1-3 to open the year, ROSTER MOVES: The Rangers have purchased the con- the team’s 3rd straight season to be exactly 1-3 after 4 G… tract of RHP Bartolo Colon (#40) from Triple-A Round Rock Overall ..................................1-3 this is also the 5th consecutive campaign to be .500 or below ahead of tonight’s scheduled start…to make room on the after 4 G (2-2 in both 2014-15)…club is T4th in the A.L. West active roster, the team optioned RHP Nick Gardewine to Home ....................................1-3 Road .....................................0-0 with OAK, 2.0 GB of HOU and LAA…Rangers did not win Round Rock…to make room on the 40-man roster, the club its season-opening series for a 4th straight season (2-2 at has transferred RHP Ricardo Rodríguez (rt. biceps tendini- Standing .............. T4th, -2.0 GB OAK in 2015, 1-2 vs. SEA in 2016, 0-3 vs. CLE in 2017)… tis) from the 10-day to the 60-day disabled list…additionally, club had won its 1st series in 4 consecutive campaigns from 1B Tommy Joseph has been assigned outright to Double-A Homestand ...........................1-3 2011-14…thru 5 G, Rangers had a 1-4 record in 2017, which Frisco. -

A's NEWS LINKS, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2018 BASEBALL RELATED ARTICLES MLB.COM A's Magic Number Stays at 7 with Loss to Halos

A’S NEWS LINKS, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2018 BASEBALL RELATED ARTICLES MLB.COM A's magic number stays at 7 with loss to Halos by Jane Lee https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/athletics-lose-series-opener-against-angels/c-295194398 Triggs to undergo thoracic outlet surgery by Jane Lee https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/andrew-triggs-to-have-thoracic-outlet-surgery/c-295088040 SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE A’s, Giants: a few things to follow in season’s final days by John Shea https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/shea/article/A-s-Giants-a-few-things-to-follow-in-13239722.php A’s get little fan support, fall to Angels 9-7 by John Shea https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/A-s-get-little-fan-support-fall-to-Angels-9-7- 13240452.php Mike Scioscia: A’s turnaround is inspiration for Angels by John Shea https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/Mike-Scioscia-A-s-turnaround-is-inspiration- 13240126.php THE MERCURY NEWS A’s lose to Angels, cry foul over potential fan interference by Dan Brown https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/09/18/as-lose-to-angels-cry-foul-over-potential-fan-interference/ THE ATHLETIC Foul play: Call stands, unravels A’s, and suddenly Tampa lurks in the shadows by Julian McWilliams https://theathletic.com/533531/2018/09/19/foul-play-call-stands-unravels-as-and-suddenly-tampa- lurks-in-the-shadows/ Sarris: A look at this season’s most surprising teams — for better and worse by Eno Sarris https://theathletic.com/532207/2018/09/19/sarris-a-look-at-this-seasons-most-surprising-teams-for- better-and-worse/ ASSOCIATED PRESS Cowart