Records of Argyll Part Three: Macnaughtan of the Fort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SB-4203-September-NA

Scottishthethethethe www.scottishbanner.com Banner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 42 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 42 36 36 NumberNumber Number 3 11 11The The The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper September May May 2013 2013 2018 Sir John De Graeme The Guardian of Scotland » Pg 16 US Barcodes V&A Dundee welcomes the world Celebrating » Pg 6 7 25286 844598 0 1 20 years of the The Magic of the Theatre ...... » Pg 14 The Battle of Prestonpans-Honouring Wigtown Book a Jacobite Rising ........................ » Pg 24 Beano Day at the Festival 7 25286 844598 0 9 National Library ........................... » Pg 31 » Pg 28 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 42 - Number 3 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Offices of publication Valerie Cairney Australasian Office: PO Box 6202 Editor Marrickville South, Sean Cairney NSW, 2204 That’s what Scots do Tel:(02) 9559-6348 EDITORIAL STAFF as the wind whirled around us. I passionate volunteers spend many Jim Stoddart [email protected] have witnessed this incredible act of personal hours away from family Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot community kindness before and am and friends to engage with people North American Office: The National Piping Centre sure some readers have helped or and the Society’s Convener David PO Box 6880 David McVey been helped at events in the past. -

MARCH - APRIL 2009 VOLUME 26, ISSUE NUMBER 2 Tartan Day Ceilidh 2009 by Marcey Hunter

The Thistledown Scottish Society of Tidewater, Inc. MARCH - APRIL 2009 VOLUME 26, ISSUE NUMBER 2 Tartan Day Ceilidh 2009 by Marcey Hunter If you missed this year’s Tar- gum tasty, if I do say so myself! tan Day Ceilidh, you sure The food this year was catered missed a good one! by the Church of the Ascension. Turnout was exceptional with What an outstanding job they did! nearly 100 people attending. In addition to the haggis, neeps & Many of them were “newbies” tatties, we enjoyed shepherd’s who had not participated in pie, curried chicken and rice, and past SST events, and by all meat pies. Everything was just accounts they had a ball! One delicious and plentiful. They sold person signed up as a mem- very affordable imported beers and ber, and there were many oth- a variety of wine. Folks were en- ers who took applications and couraged to BYOB, and many did. promised to join soon. For dessert we had a large cake, This year’s committee was decorated with our SST logo, chaired by Edward Brash. which was purchased at NAAS Thanks to Edward for organiz- No less than four fiddlers entertained at this year’s Tartan Day Ceilidh. Bakery in Norfolk. Delish! ing such a fun and meaningful event! There were tartan swatches on each table, Among our challenges was to transform and fresh flowers sporting tartan ribbons as the church’s main hall into a Tartan para- well. Votive candles and Christmas lights dise. I think we did pretty well, actually! gave the whole room just the right atmos- phere. -

SB-4309-March-NA.Pdf

Scottishthethethethe www.scottishbanner.com Banner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 44 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2020 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 43 36 36 NumberNumber Number 911 11The The The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper May MarchMay 2013 2013 2020 The Broar Brothers The Rowing Scotsmen » Pg 16 Celebrating USMontrose Barcodes Scotland’s first railway through The 1722 Waggonway 7 25286 844598 0 1 » Pg 8 the ages » Pg 14 Highland, 7 25286 844598 0 9 Scotland’s Bard through Lowlands, the ages .................................................. » Pg 3 Final stitches sewn into Arbroath Tapestry ............................ » Pg 9 Our Lands A Heritage of Army Pipers .......... » Pg 32 7 25286 844598 0 3 » Pg 27 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 43 - Number 9 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Offices of publication Valerie Cairney Australasian Office: PO Box 6202 Editor Bagpipes-the world’s instrument Marrickville South, Sean Cairney NSW, 2204 pipes attached where the legs and In this issue Tel:(02) 9559-6348 EDITORIAL STAFF neck would be. Today you will find The sound of Scotland made its way Jim Stoddart [email protected] both synthetic and leather varieties recently across the Atlantic Ocean The National Piping Centre available, with fans of each. -

Finance/Performance Committee Meeting Order Paper

Rangitikei District Council Telephone: 06 327-0099 Facsimile: 06 327-6970 Finance/Performance Committee Meeting Order Paper Thursday, 27 August 2015, 9.30 am Council Chamber, Rangitikei District Council 46 High Street, Marton Website: www.rangitikei.govt.nz Email: [email protected] Chair Deputy Chair His Worship the Mayor, Andy Watson Cr Nigel Be!sham Membership Councillors Cath Ash, Tim Harris, Dean McManaway, Rebecca McNeil, Soraya Peke- Mason, Ruth Rainey and Lynne Sheridan Please Note: Items in this agenda may be subject to amendments or withdrawal at the meeting. It is recommended therefore that items not be reported upon until after adoption by the Council. Reporters who do not attend the meeting are requested to seek confirmation of the agenda material or proceedings of the meeting from the Chief Executive prior to any media reports being filed. Rangitikei District Council Finance/Performance Committee Meeting Order Paper — Thursday 27 August 2015 9:30 a.m. Contents 1 Welcome 2 2 Council Prayer 2 3 Apologies/leave of absence 2 4 Confirmation of order of business 2 5 Confirmation of Minutes 2 Attachment 1, pages 7-13 6 Chair's report 2 Tabled 7 Consideration of applications to Community Initiatives Fund 2015/16 (round 1).2 Attachment 2, pages 14-124 8 Consideration of applications to Events Sponsorship Scheme 2015/16 (round 1) 3 Attachment 3, pages 125-144 9 Financial report — draft full year 2014/15 4 Attachment 4, pages 145-165 10 Discounted rates at the waste transfer stations for pensioners 4 Attachment 5, pages 166-167 -

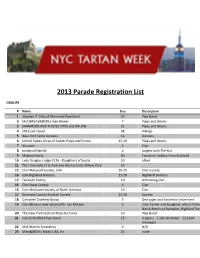

2013 Parade Registration List

2013 Parade Registration List GROUPS # Name Size Description 1 Stephen P. Driscoll Memorial Pipe Band 25 Pipe Band 2 McClafferty's Nae Breeks 7 Pipes and Drums 3 SHAMROCK AND THISTLE PIPES and DRUMS 31 Pipes and Drums 4 2013 Jarl Squad 38 Vikings 5 New York Celtic Dancers 12 Dancers 6 United States Corps of Cadets Pipes and Drums 15-20 Pipes and Drums 7 Nicolson 5 Clan 8 mcdonald family 4 singers with The Kist 9 Mackay family 30 Family on holiday from Scotland 10 Lady Douglas Lodge #126 - Daughters of Scotia 10 other 11 The University of St Andrews Alumni Club of New York 15 12 Clan MacLeod Society, USA 20-25 Clan society 13 USA Highland Dancers 15-20 Highland Dancers 14 Fairbairn Family 10 Armstrong clan 15 Clan Shaw Society 5 Clan 16 Clan MacLaren Society of North America 10 Clan 17 Dutchess County Scottish Society 15-20 Society 18 Campbell Crockett Group 3 One piper and two tenor drummers 19 Clan McLean International/Dr. Les McLean 2 Clan, Father and Daughter, who is former North America Champion, Highland Dancing 20 The New York Scottish Pipes & Drums 10 Pipe Band 21 City of Sheffield Pipe Band 15 3 pipers - 1 side drummer - 11 band members 22 Mid Atlantic Scots4tots 0 N/A 23 Mary's Meals USA, Inc 25 none 24 McClafferty's Nae Breeks 8 Pipes and Drums 25 Saint Andrew's Society of the State of New York 40 Charitable Organization 26 Penn Dixie Band 7 Professional Band on Float - OUR CONTRACT REQUIRED 27 Long island Scottish/American Society 12 Society 28 American-Scottish Foundation 40 Organization 29 Hudson Highlands Pipe Band 15-20 Pipes and drums 30 New York Lyric Circus 5 organization 31 Scots American Athletic Association 25 N/A 32 New York Caledonian Club 75 Scottish Organization 33 Campbell Crockett Band 3 1 Piper and 2 Tenor drummers 35 STANLEY ODD 7 SCOTTISH HIP HOP BAND 36 New York Metro Pipe Band 30 Pipe Band 37 United States Naval Academy Pipes and Drums 25 Pipes and Drums with Highland Dancers 38 The King's Highlanders 2 Pipe and drum duet 39 Nessie c/o Suzanne Present 7 Loch Ness Monster 40 Mt. -

SB-4202-August

Scottishthethethethe www.scottishbanner.com Banner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 42 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 42 36 36 NumberNumber Number 211 11 TheThe The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest internationalinternational international Scottish Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper May MayAugust 2013 2013 2018 The Sound of THE PIPING ISSUE! Scotland » Pg 16 TattooUS Barcodes to celebrate human potential for ‘The Mackintosh 150 Sky’s the Limit’ in 2018 Celebrating one of Glasgow’s great sons » Pg 8 » Pg 23 7 25286 844598 0 1 Poppies flourish at The Edinburgh Edinburgh’s Floral Clock ..... » Pg 10 The piping world International Festival comes to Glasgow ................... » Pg 14 Braemar-Scotland’s lights up the capital Royal Gathering ........................ » Pg 30 7 25286 844598 0 9 » Pg 14 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 42 - Number 2 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Offices of publication Valerie Cairney Australasian Office: PO Box 6202 Editor Marrickville South, Sean Cairney The gift of Scotland NSW, 2204 Tel:(02) 9559-6348 EDITORIAL STAFF Scottish theme and friendliness round and today I feel fortunate to Jim Stoddart [email protected] about them. Passing on the gift carry on the legacy of my parents Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot of Scotland to his three boys was through the Scottish Banner. -

( 1 ) Children of Arthur: the Once and Future King by Michael Andrew

Children of Arthur: The Once and Future King By Michael Andrew McCabe Preface: It is difficult for one claiming descent from a legend. One is constantly forced to battle both reasonable skepticism and the more fanciful elements of the legend itself. Perhaps no legendary figure is more difficult to claim as an ancestor than Arthur, King of the Britons. Nonetheless, a great many people claim Arthur as an ancestor. In my family, it has been part of the general lore for many generations. I’m not sure why it matters, but the claims persist: Arthur is reportedly one of my progenitors. I do not personally believe that it is possible to prove such a genealogical connection. The time itself is too remote for written records to have survived intact. Various oral histories and legends themselves disagree as to the time, place, and nature of the Arthurian Realm. Arthurian legend itself is rife itself with tales of infidelity, illegitimate offspring, and questionable parentage. Lacking DNA evidence, the pseudo-science of genealogy is itself now suspect. ( 1 ) Given that I cannot prove or disprove the genetic connection between King Arthur and myself, I shall endeavor to document both the alleged kinship and the kernel of truth that I believe can be found within the many stories that I’ve been told over the years. Readers lacking patience or imagination are warned to stop now and simply conclude that the author is “off his medication.” So, Who was King Arthur? As is often the case, the answer depends upon whom you ask. Answers from England: Wikipedia, that great source for the modern plagiarist, begins by classifying Arthur as a Mythical British King; preceded by Uther Pendragon and succeeded by Constantine III. -

St Andrew Highland Gathering

the www.scottishbanner.com Scottishthethethe Australasian EditionBanner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 41 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 41 36 36 Number Number Number 7 11 The11 The The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international ScottishScottish Scottish newspapernewspaper newspaper May JanuaryMay 2013 2013 2018 Scotland Let it What’s new for 2018 » Pg 14 snowUS Barcodes Creating snow and boosting the Highland economy »7 Pg25286 16 844598 0 1 7 25286 844598 0 9 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 Band on Australia $4.00; North American $3.00; N.Z. $3.95 2018 - A Year in Piping .......... » Pg 6 Nigel Tranter: the Run Scotland’s Storyteller ........... » Pg 25 Scottish snowdrop’s Playing pipes with - A sign of the season .............. » Pg 29 Robert Burns: Sir Paul McCartney Scotland’s Bard ........................ » Pg 30 » Pg 6 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Scottishthe Volume Banner 41 - Number 7 The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Valerie Cairney January-Celebrating two great Scots Editor Sean Cairney growing up. When Uncle John came however) and the story has crossed to town we all chipped in and helped over into books and a film and surely EDITORIAL STAFF where we could with the shows. It must be considered one of the great Jim Stoddart Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot was only a little later in childhood I stories about ‘man’s best friend’. -

US October 04

North American Edition the www.scottishbanner.com 33 Scottish Banner Years Strong - 1976-2009 A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 33 Number 4 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper October 2009 Lockerbie and Its Aftermath p. 14-15 Let There Be Light on Glasgow Cathedral p. 17 What’s So Good About Scottish Country Dancing? p. 26 Australia $3.30; North American $2.75; N.Z. $3.50; U.K. £1.50 Genealogy pg. 04 Scottish Recipes pg. 05 Dressing Like a Gentleman pg. 07 October is Scot Pourri pg. 10 Breast Cancer This Month in Scottish History pg. 19 Awareness Scots Events pg. 24 Month Page 2 ~ North American Edition-October 2009 THE SCOTTISH BANNER hall is currently serving as an emergency morgue. Volume 33, Number 4 Scottish Banner Says Last night’s crew and passengers from the PanAm Jumbo along with some local people lay dead. Shock at the release of Dumfries and Galloway police estimated more than 150 bodies lay in six acres. Lockerbie One writer told of his experience looking over a dyke, at the remains of the cabin of the Jumbo jet. Bomber... It lay broken on its side like a giant toy discarded Last month the by a spoiled child. release of Abdel Baset Yet this mindless fit of insanity had the bloody Mohamed Al Megrahi, hand of a mindless zealot behind it. the Lockerbie Bomber, by Scottish Justice Sheep Grazed Minister Kenny Mac- Walking past an old churchyard, sheep grazed on Askill sent shock the left of the field the reporter recalled looking twice at something motionless, possibly a dead, sheep with waves, not only a gash in its side. -

The Firefox Web Browser Has Become the First Major Software Available In

The Firefox web browser has become the first RaDrlc hopes that this major software available in the Scots language. The new language option will project, 1ed by Edinburgh-based localization provider change thatby allowing leam- Rubric, seeks to promote the language and will be ers and fluent speakers to available for users from the 10tt'of August 2021. browse the web in Scots. Recognition ofthe Scots language has grown A renaissance of the Scots language recently in Scottish schools, parliament and on social The 2011 Scottish census renorted that 1 .9 mi1- media. Howeveq speakers have had limited options lion people could speak. read, write or understand for software in their own language. Continued on page 5 Fall begins in the Northern Hemisphere when the Sun is perpendicular to the equator. This day has equar hours of day and night. The first day of Fali is also called the Autumnal Equinox. In many areas, it coincides with harvests. The first day of Fall happens each year between September22 and 24. ln 2021 theAutumnai Equinox occurs on September22 TheArmstrong Clan Societywas organized on OctoberA, 'lg8l and is incorporated in the State of Geofgia, USA, The Society is recognized as a Section 501 (c) (3) not for profit organjzation and exempt from the United States Federal lncome Taxes. On September 24, 1984, the Lord Lyon, King of Arms in Scofland, granted warrant to the lyon Clerk to matriculate in the public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland in the name of the Armstrong Clan Society, ,,Semper lnc,, the Coat of Arms to the right of this paragraph. -

The Origins of the Clan Boyd and Their Place in History Ebook

BOYD: THE ORIGINS OF THE CLAN BOYD AND THEIR PLACE IN HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Iain Gray | 32 pages | 01 Apr 2006 | Lang Syne Publishers Ltd | 9781852172206 | English | Glasgow, United Kingdom Boyd by Iain Gray Paperback Book Free Shipping! for sale online The Earl of Arran also escaped to the Low Countries where he died. His widow, Princess Mary, was then compelled to marry the elderly Lord Hamilton who was created Earl of Arran and thus made the Hamiltons next in line to the throne rather than the Boyds. The line of Boyds did however continue through the second son of Lord Boyd and the title was restored in The 10th Lord Boyd was made Earl of Kilmarnock by Charles II in but less than a century later the title was stripped for the part played by the 4th Earl in the Jacobite rebellion. The title was passed through the female line to the Earl's second son who inherited the title of the Earl of Erroll and adopted the name of Hay. He was succeeded in by the 7th Lord Kilmarnock. An origin in the Isle of Bute 'Bod' in Gaelic has also been promoted. Their reputed Anglo- Norman ancestor was Simon, younger brother of Walter the first High Steward, and the fess-chequey in the Boyd arms might support this origin. They supported Bruce in the struggle for Independence and following Bannockburn in Sir Robert Boyd was granted the lands around Kilmarnock lately forfeited by Balliol. Robert Boyd became Lord Boyd in and the family enjoyed a brief ascendency. -

F,Ppv Fo Erb Fav Hj 8Rl /L T-Lt+- O Th 47 /Re//Pt" {+Ot+- Q4il* Edi/,0*

We have lost an irreplaceable treasure, Purdy Mcleod o A great man has passed he lived in many locations and attended and he will be missed. Purdy many schools in South Carolina until Belvin Mcleod, Jr., 93, of graduating from Conway High School Columbi4 South Carolina, died at the age of sixteen. on Saturday, May 8, 2021. He then attended Wofford Co1- He lovedhis family,his chil- lege untiljoiningtheNavy in 1945. He dren, his country South Caro- served aboard ships in the Pacific and lina - especially the 1ow country, in Japan at the end of WMI. pecan trees, his heritage, his He then returned to Wofford work and his friends, and he graduating with aB.A. in 1949. loved meeting people and spend- He entered active duty as an of- ing time with friends, new and o1d. ficer in the US Army completing the Bom in Meggett, Charles- Reserve Officers Training Course. He ton County, South Carolina on served in Japan, Korea, the United August 13, 1927, he was the States, Germany and Vietnam. third child ofthe late Rev. Purdy o He retired an Lrfantry Colonel in B. Mcleod, Sr. and Ethel the RegulmArmy nJaruary I975. Geftrude Horres_ Mcleod. As He married Emily Elizabeth tr1 the son of a Methodist ministeq Continued on page 9 # f,ppv Fo erb Fav Hj 8rl /l t-lt+- o th 47 /re//pt" {+ot+- q4il* edi/,0*... [" vv u 0 l' How about a helping of "Slum Gullion?" Growing up in Jacksonville, Florida, and being brought up by my beloved grandmother, A1*i" Bob.rta McDonald, I knew all about and really loved "Slum Gullion."^'.