(Second Reader) MA Film Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hbo Premieres the Third Season of Game of Thrones

HBO PREMIERES THE THIRD SEASON OF GAME OF THRONES The new season will premiere simultaneously with the United States on March 31st Miami, FL, March 18, 2013 – The battle for the Iron Throne among the families who rule the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros continues in the third season of the HBO original series, Game of Thrones. Winner of two Emmys® 2011 and six Golden Globes® 2012, the series is based on the famous fantasy books “A Song of Ice and Fire” by George R.R. Martin. HBO Latin America will premiere the third season simultaneously with the United States on March 31st. Many of the events that occurred in the first two seasons will culminate violently, with several of the main characters confronting their destinies. But new challengers for the Iron Throne rise from the most unexpected places. Characters old and new must navigate the demands of family, honor, ambition, love and – above all – survival, as the Westeros civil war rages into autumn. The Lannisters hold absolute dominion over King’s Landing after repelling Stannis Baratheon’s forces, yet Robb Stark –King of the North– still controls much of the South, having yet to lose a battle. In the Far North, Mance Rayder (new character portrayed by Ciaran Hinds) has united the wildlings into the largest army Westeros has ever seen. Only the Night’s Watch stands between him and the Seven Kingdoms. Across the Narrow Sea, Daenerys Targaryen – reunited with her three growing dragons – ventures into Slaver’s Bay in search of ships to take her home and allies to conquer it. -

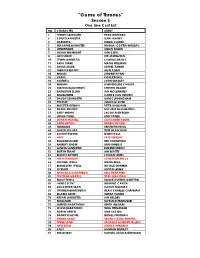

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Culture Sophie Turner Kit Harington Gwendoline Christie As the Final

Culture As the final series of Game Of Thrones arrives on our screens, Anna Bonet reflects on the rise of its biggest names Richard Madden Sophie Turner Before winning the part of Robb Stark, Turner took on the role of Sansa Stark aged Madden had appeared in various stage 14 after she was encouraged to audition for productions – most notably starring as Romeo the part by her drama teacher. The show has at The Globe Theatre in 2007. After three earned her international recognition, and she seasons as the heir of Winterfell, Madden uses her platform to regularly speak about acted alongside women’s rights and mental health stigma. Keeley Hawes in Turner became a Women for Women Bodyguard, the BBC International patron in 2017, has starred in films including Another drama from Jed Me and X-Men: Apocalypse, and got engaged to Jonas brother Mercurio that had Joe last year – the pair are rumoured to be marrying this summer. 10million people gripped last year. Maisie Williams His role as David Turner’s on-screen sister and real-life best friend Budd won him a Maisie Williams has played Arya Stark since Golden Globe for day one of GOT. Following this, she’s had a Best Actor in a recurring role in Doctor Who and played parts Television Drama, in films such as The Falling, The Book Of Love as well as a swathe and iBoy. Towards the end of 2018, Williams of devoted fans. starred in the stage production I And You at the Hampstead Theatre in London, and has turned Gwendoline Christie her hand to tech, co-founding Daisie, a social After expressing a desire media app that brings together creatives by to act to an agent, 6ft 3in providing a space to share and collaborate. -

HBO Makes History with 137 Primetime Emmy® Nominations

HBO makes history with 137 primetime Emmy® nominations HBO has received 137 Primetime Emmy® nominations, breaking records with the highest number in HBO history, and making this its ninth consecutive year in which it receives 100 or more. The announcement was made today in Los Angeles. GAME OF THRONES set an Emmy® record with the most nominations in a single year after receiving 32 nominations. Also highlighted was the original limited series CHERNOBYL, received 19 nominations, while the comedy series BARRY was recognized with 17 nominations. VEEP, TRUE DETECTIVE and LAST WEEK TONIGHT WITH JOHN OLIVER received 9 nominations each. HBO original films BREXIT, DEADWOOD and MY DINNER WITH HERVÉ, as well as the original documentaries JANE FONDA IN FIVE ACTS, LEAVING NEVERLAND and THE INVENTOR: OUT FOR BLOOD IN SILICON VALLEY were also recognized. The winners of the 71st annual Primetime Emmy® Awards will be announced on September 22nd in Los Angeles. Full list of HBO nominations: · 32 nominations for GAME OF THRONES, including Outstanding Drama Series, Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series (Kit Harington), Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series (Emilia Clarke), 4 for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series (Gwendoline Christie, Lena Headey, Sophie Turner, Maisie Williams), 3 for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series (Alfie Allen, Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, Peter Dinklage), Outstanding Guest Actress in a Drama Series (Carice van Houten), 3 for Outstanding Directing for a Drama Series (David Benioff & D.B. Weiss, David Nutter, -

“Sharing the Responsibility for Educating Our Children” Don’T You Worry Bout a Thing

Celerity Achernar Charter School would like to thank the following people for their contributions to our dance show: Celerity Achernar Charter le gustaría agradecer a las siguientes personas por sus contribuciones a nuestro espectáculo: SPECIAL THANKS TO: Nadia Shaiq, Interim Chief Executive Officer and Chief Academic Officer Kendal Turner, Chief Financial Officer John Vargas, Chief Operations Officer Sergio Alvarez, Assistant Director of School Services Autrilla Gillis, Director of Expanded Learning Rob J. Thrash IV, Director of Pupil Services Theresa Jefferson, Director of Special Education Joe Ortiz, Director of IT Karina Solis, Student Data Coordinator April Thomas, Performing Arts Coordinator Matthew Bamberg-Johnson, Performing Arts Coordinator Erik Conley, Creative Media Coordinator Shawn Porter, Creative Media Assistant Coordinator Jason Rios, Principal Chris Smith, Dance Instructor Keyaama Bray, Dance Instructor & Costume Coordinator Masina Torres, Vocal Instructor Roderick Davis, Acting Instructor Mr. Muhammad, Drum Instructor Carmen Chavez, Costume Coordinator Eberth Martinez, Sound Technician Claudia Fuentes, Office Manager Ernie Dominguez, Community Liaison A special and gracious thanks to the amazing and dedicated teachers, staff, PTO and Parent Volunteers at Celerity Achernar Charter School, and the entire Performing Arts Department. 310 E. El Segundo Blvd., Compton, CA 90222 Phone: (310) 764-1234 www.CelerityCalifornia.org “Sharing The Responsibility For Educating Our Children” Don’t You Worry Bout a Thing . WELCOME... Music by: Stevie Wonder • Choreographed by: Andre Kinney On behalf of all of Celerity Achernar Charter School staff, it is a pleasure to 9:30am: Ruvalcaba (1st grade) Ricardo Beltran, Aiden Carrillo Corona, Allison welcome you to our musical performance of “Sing.” Our thanks go to many Cumplido, Isabella De La Cruz, Adrian Dominguez, Citlali Gamboa, Crystal Gonzalez people for helping make this possible. -

The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror

The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films 334 West 54th Street Los Angeles, California 90037-3806 Phone: (323) 752-5811 e-mail: [email protected] Robert Holguin (President) Dr. Donald A. Reed (Founder) Publicity Contact: Karl Williams [email protected] (310) 493-3991 “Gravity” and “The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug” soar with 8 Saturn Award nominations, “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire,” scores with 7, “Iron Man 3,” “Pacific Rim,” “Star Trek Into Darkness and Thor: The Dark World lead with 5 nominations apiece for the 40th Annual Saturn Awards, while “Breaking Bad,” “Falling Skies,” and “Game of Thrones” lead on TV in an Epic Year for Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror LOS ANGELES – February 26, 2014 – Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity and Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug both received 8 nominations as the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films today announced nominations for the 40th Annual Saturn Awards, which will be presented in June. Other major contenders that received major nominations were The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim, Star Trek Into Darkness, The Book Thief, Her, Oz The Great anD Powerful and Ron Howard’s Rush. Also making a strong showing was the folk music fable InsiDe Llewyn Davis from Joel and Ethan Coen highlighting their magnificent and original work. And Scarlett Johansson was the first Best Supporting Actress to be nominated for her captivating vocal performance in Spike Jones’ fantasy romance Her. For the Saturn’s stellar 40th Anniversary celebration, two new categories have been added to reflect the changing times; Best Comic-to-Film Motion Picture will see Warner’s Man of Steel duking it out against Marvel’s Iron Man 3, Thor: The Dark WorlD and The Wolverine! The second new category is Best Performance by a Younger Actor in a Television Series – highlighting the most promising young talent working in TV today. -

Report Card 2014 | 74 Chapter 4: Right to an Adequate Standard of Living

“ The challenges facing the families we talked to are heartbreaking. Every single parent wants to give their children the best they can. But the impact of five brutal budgets is pushing them to the limits. Many parents have told us that putting food on the table for their children often means going without food themselves.” Fergus Finlay, Chief Executive, Barnardos Children’s Rights Alliance Report Card 2014 | 74 Chapter 4: Right to an Adequate Standard of Living Grade D Boost for local children By Jack Gleeson PARENTS and young children in Finglas are set to benefit from a new childhood programme designed to improve the lives of children in disadvantaged areas. Finglas was one of 13 locations nationwide selected for the €30 million Area-Based Childhood (ABC) early intervention programmes to support health and social projects in several countries. The ABC programme targets investment in evidence-based early In The News interventions – from pregnancy onwards - to improve the lives and futures for children and families living in areas of disadvantage. Local TD Róisín Shortall (Ind) welcomed the inclusion of Finglas in the children and parenting initiative, which was the result of a successful application from Better Finglas, a consortium made up of local groups, schools, Dublin City Council and State agencies. “I fought hard to have a commitment to such funding contained in the Programme for Government,” said Deputy Shortall. “I am glad to see that this is one promise the Government appears to be delivering on. Early intervention programmes are vital if we are ever to break the cycle of poverty and exclusion in large parts of Dublin.“It is about giving kids a chance in life and preventing problems before they begin. -

TH256-15 Adapting Shakespeare for Performance

TH256-15 Adapting Shakespeare for Performance 21/22 Department Theatre and Performance Studies Level Undergraduate Level 2 Module leader Ronan Hatfull Credit value 15 Module duration 10 weeks Assessment 100% coursework Study location University of Warwick main campus, Coventry Description Introductory description Adapting Shakespeare for Peformance is a practice-based module that invites students to engage in the adaptation process and produce their own creative responses to the plays of William Shakespeare. This module will challenge students to produce their own interpretation of plays which have helped shape how adaptation is received and practiced. An intrinsic part of Shakespeare’s legacy is the adaptation of his work on stage, page and screen. Shakespeare himself was a consummate adapter, drawing on pre-existing literary and theatrical materials and re-working these for his audiences, for whom his plays were a form of popular entertainment. How is Shakespeare reconceptualised in the context of popular culture and what methods do modern artists use to render his work accessible? This module will challenge the perception of what can be perceived as an adaptation of Shakespeare and each 180-minute workshop will involve practical exploration of different media, including poetry, prose, film, television and theatre. Students will be asked to create a three-minute mini-adaptation/pitch in response to each week’s material and asked to present this at the following seminar. Using this accumulative creative material and case studies as models, the module will culminate with the creation of group adaptations, which will be rehearsed in Weeks 8 and 9 and presented during Week 10. -

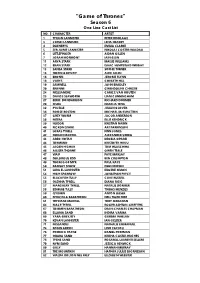

“Game of Thrones” Season 6 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 6 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 12 BRAN STARK ISAAC HEMPSTEAD WRIGHT 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 27 BERIC DONDARRION RICHARD DORMER 28 OSHA NATALIA TENA 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 38 MEERA ELLIE KENDRICK 39 HODOR KRISTIAN NAIRN 40 RICKON STARK ART PARKINSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 49 THOROS OF MYR PAUL KAYE 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 55 BLACKFISH TULLY CLIVE RUSSELL 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 58 EDMURE TULLY TOBIAS MENZIES 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 69 YARA GREYJOY GEMMA WHELAN 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 74 ROBIN ARRYN LINO FACIOLI 76 PODRICK -

Downloadable Activity Book That She Distributed to Local Shelters and Veterinarians That Educates Children on the Many Responsibilities of Pet Ownership

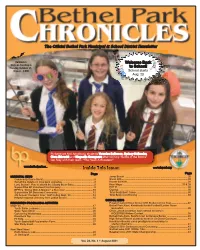

The Official Bethel Park Municipal & School District Newsletter Halloween Welcome Back Trick-or-Treating is Sunday, October 31, to School! from 6 - 8 PM School starts Aug. 23 Pictured are Neil Armstrong students Veronica Balkovec, Sydney Kellander, Ciera Erbrecht and Magnolia Cavagnaro after winning “Battle of the Books” last May with their team, “The Read-A-Skeaters!” www.bethelpark.net Inside This Issue: www.bpsd.org Page Page MUNICIPAL NEWS Jump Bunch ..........................................................................................25 Community Day is Back! ..........................................................................3 Shoot 360 ................................................................................................25 Get all the details on local park upgrades ..............................................3 Karate for Kids ........................................................................................26 Love Books? Plan to attend the Library Book Sale! ..............................5 Krav Maga ......................................................................................25 & 28 Support the BP Volunteer Fire Company ................................................9 HIIT IT ......................................................................................................28 BPPD’s “Socks With A Mission” a Success! ........................................10 Qigong ....................................................................................................29 Support the BP Business -

Download This PDF File

UCCS | Undergraduate Research Journal | 10.2 Arguing Progressivism in a Movie Theater Far Far Away By Michael Wheeler Abstract The purpose of this paper is to analyze feminism as it pertains to the Star Wars film series. After examining the opinions of other authors and analyzing scenes from the film, can the female characters be considered progressive as it pertains to feminism? Various authors of other scholarly articles as well as novels, which contain collections of scholarly articles, were used to add ethos to the argument. Biographies and scenes from the Star Wars films themselves were analyzed to gather information on specific female characters from the film and to analyze their actions and personas. Per these sources, there is high praise for the female characters in Star Wars. Characters, both in the foreground and the background of the films, have different stories and attributes that make them strong as characters. These strengths and the characters’ abilities to react to new challenges result in them being deemed progressive by modern society. It will be a pleasure seeing how the series continues to move forward and how it will continue to experiment with the characters and what challenges the characters will face. Introduction Due to the prominence of the male Jedi within the Star Wars film series such as Obi-wan, Yoda, Luke, and Mace Windu, it might seem like the female Jedi are non-existent or rare. However, there were a fair number of female Jedi represented within the Star Wars film series. There were Depa Billada, Aayla Secura, Shaak Ti, Adi Gallia, Luminara Unduli, and many more (Sansweet, 2008; Hidalgo and Beecroft, 2016; et al). -

Secrets of Star Wars

SECRETS OF STAR WARS Podcast Notes and Analysis By Annie Powell BASED ON THE SECRETS OF STAR WARS PODCAST BY FATHER RODERICK AND DOM BETTINELLI Notes: In this document, the notes from the podcast are typed in black. Follow -up notes and analysis by Annie Powell are typed in blue. These follow-up notes were added after the movie release. The original notes were kept in the order presented in the podcast shows, but were sorted by the topics of: CAST PROPS/LOCATIONS/SETS COSTUMES/CHARACTERS PLOT The Secrets of Star Wars podcast aired from May 25, 2013 - April 21, 2015, and was a presentation by Father Roderick and Dom Bettinelli. Credits: Some follow-up information was obtained from the book Star Wars: The Force Awakens: The Visual Dictionary by Pablo Hidalgo. Cast Carrie Fisher was the first actor to announce her return. CASTING CALL Late teen female, fit with a good sense of humor, independent. Daisy Ridley; Rey. Young twenty-something male, witty and smart, fit, but not traditionally good looking. John Boyega; Finn/FN-2187 Late twenty-something male, handsome, fit and confident. Oscar Isaac; Poe Dameron. 70 something male with strong opinions and tough demeanor. Doesn’t need to be particularly fit. Probably Max von Sydow/Lor San Tekka, but really only the general age is right. Late teen female, tough, smart and fit. Gwendoline Christie/Captain Phasma, even though the age isn’t quite right. 40 something male, fit, military-type. Domhnall Gleeson/General Hux. 30 something male, intellectual. Adam Driver/Kylo Ren. Casting call 1: Daisy Ridley, 2: Domhnall Gleeson, 3: Oscar Isaac, 4: Max von Sydow, 5: not cast yet, 6:?, 7: could be Domhnall Gleeson but maybe other minor character.