Arxiv:1907.01981V3 [Astro-Ph.IM] 30 Dec 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomie in Theorie Und Praxis 8. Auflage in Zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski

Astronomie in Theorie und Praxis 8. Auflage in zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Beobachtungen mit bloßem Auge 37 Motivation 37 Hilfsmittel 38 Drehbare Sternkarte Bücher und Atlanten Kataloge Planetariumssoftware Elektronischer Almanach Sternkarten 39 2 Atmosphäre der Erde 49 Aufbau 49 Atmosphärische Fenster 51 Warum der Himmel blau ist? 52 Extinktion 52 Extinktionsgleichung Photometrie Refraktion 55 Szintillationsrauschen 56 Angaben zur Beobachtung 57 Durchsicht Himmelshelligkeit Luftunruhe Beispiel einer Notiz Taupunkt 59 Solar-terrestrische Beziehungen 60 Klassifizierung der Flares Korrelation zur Fleckenrelativzahl Luftleuchten 62 Polarlichter 63 Nachtleuchtende Wolken 64 Haloerscheinungen 67 Formen Häufigkeit Beobachtung Photographie Grüner Strahl 69 Zodiakallicht 71 Dämmerung 72 Definition Purpurlicht Gegendämmerung Venusgürtel Erdschattenbogen 3 Optische Teleskope 75 Fernrohrtypen 76 Refraktoren Reflektoren Fokus Optische Fehler 82 Farbfehler Kugelgestaltsfehler Bildfeldwölbung Koma Astigmatismus Verzeichnung Bildverzerrungen Helligkeitsinhomogenität Objektive 86 Linsenobjektive Spiegelobjektive Vergütung Optische Qualitätsprüfung RC-Wert RGB-Chromasietest Okulare 97 Zusatzoptiken 100 Barlow-Linse Shapley-Linse Flattener Spezialokulare Spektroskopie Herschel-Prisma Fabry-Pérot-Interferometer Vergrößerung 103 Welche Vergrößerung ist die Beste? Blickfeld 105 Lichtstärke 106 Kontrast Dämmerungszahl Auflösungsvermögen 108 Strehl-Zahl Luftunruhe (Seeing) 112 Tubusseeing Kuppelseeing Gebäudeseeing Montierungen 113 Nachführfehler -

Hercules a Monthly Sky Guide for the Beginning to Intermediate Amateur Astronomer Tom Trusock - 7/09

Small Wonders: Hercules A monthly sky guide for the beginning to intermediate amateur astronomer Tom Trusock - 7/09 Dragging forth the summer Milky Way, legendary strongman Hercules is yet another boundary constellation for the summer season. His toes are dipped in the stream of our galaxy, his head is firm in the depths of space. Hercules is populated by a dizzying array of targets, many extra-galactic in nature. Galaxy clusters abound and there are three Hickson objects for the aficionado. There are a smattering of nice galaxies, some planetary nebulae and of course a few very nice globular clusters. 2/19 Small Wonders: Hercules Widefield Finder Chart - Looking high and south, early July. Tom Trusock June-2009 3/19 Small Wonders: Hercules For those inclined to the straightforward list approach, here's ours for the evening: Globular Clusters M13 M92 NGC 6229 Planetary Nebulae IC 4593 NGC 6210 Vy 1-2 Galaxies NGC 6207 NGC 6482 NGC 6181 Galaxy Groups / Clusters AGC 2151 (Hercules Cluster) Tom Trusock June-2009 4/19 Small Wonders: Hercules Northern Hercules Finder Chart Tom Trusock June-2009 5/19 Small Wonders: Hercules M13 and NGC 6207 contributed by Emanuele Colognato Let's start off with the masterpiece and work our way out from there. Ask any longtime amateur the first thing they think of when one mentions the constellation Hercules, and I'd lay dollars to donuts, you'll be answered with the globular cluster Messier 13. M13 is one of the easiest objects in the constellation to locate. M13 lying about 1/3 of the way from eta to zeta, the two stars that define the westernmost side of the keystone. -

1949 Celebrating 65 Years of Bringing Astronomy to North Texas 2014

1949 Celebrating 65 Years of Bringing Astronomy to North Texas 2014 Contact information: Inside this issue: Info Officer (General Info)– [email protected]@fortworthastro.com Website Administrator – [email protected] Postal Address: Page Fort Worth Astronomical Society July Club Calendar 3 3812 Fenton Avenue Fort Worth, TX 76133 Celestial Events 4 Web Site: http://www.fortworthastro.org Facebook: http://tinyurl.com/3eutb22 Sky Chart 5 Twitter: http://twitter.com/ftwastro Yahoo! eGroup (members only): http://tinyurl.com/7qu5vkn Moon Phase Calendar 6 Officers (2014-2015): Mecury/Venus Data Sheet 7 President – Bruce Cowles, [email protected] Vice President – Russ Boatwright, [email protected] Young Astronomer News 8 Sec/Tres – Michelle Theisen, [email protected] Board Members: Cloudy Night Library 9 2014-2016 The Astrolabe 10 Mike Langohr Tree Oppermann AL Obs Club of the Month 14 2013-2015 Bill Nichols Constellation of the Month 15 Jim Craft Constellation Mythology 19 Cover Photo This is an HaLRGB image of M8 & Prior Club Meeting Minutes 23 M20, composed entirely from a T3i General Club Information 24 stack of one shot color. Collected the data over a period of two nights. That’s A Fact 24 Taken by FWAS member Jerry Keith November’s Full Moon 24 Observing Site Reminders: Be careful with fire, mind all local burn bans! FWAS Foto Files 25 Dark Site Usage Requirements (ALL MEMBERS): Maintain Dark-Sky Etiquettehttp://tinyurl.com/75hjajy ( ) Turn out your headlights at the gate! Sign -

2020 the Best of the Rest of the Advanced Observing Programs

The Texas Star Party - Advanced Observing Program - 2020 The Best of the Rest of the Advanced Observing Programs This year, 2020, is a continuation of the twentieth year of visual observing of the Texas Star Party Advanced Observing Programs. The Advanced Observing Program was initiated to educate and challenge observers to locate and observe those objects they might have considered too difficult, if not impossible to find and/or see visually, beforehand. There is no better place to push the visual limit than under the dark transparent West Texas sky. Too often observers stop at the “NGC Limit” and never try to locate objects that begin with names like Arakelian, Minkowski, Palomar or Sanduleak. Such Name Intimidation is nothing more than becoming overwhelmed by the seemingly exalted difficulty of the object merely due to its unfamiliar name. A large telescope is NOT required to observe most of these objects. The listed objects are best located and observed by careful and precise star-hopping. It is most imperative that the observer know exactly where in the field to look when the object is located, especially if some object turns out to be truly “light challenged” in their particular telescope. By using various magnifications and a combination of averted and direct vision along with a large degree of patience - eventually the object will be seen. Give the sky a chance and it will come to you. The standard observing rule is if you think you see the object at least three times, then you probably Really Did See It - Log it - and go on to the next object. -

Annual Report 2013 E.Indd

2013 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL RADIO ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY 1 NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE 493 EMPLOYEES 40 PRESS RELEASES 462 REFEREED SCIENCE PUBLICATIONS NRAO OPERATIONS $56.5 M 2,100+ ALMA OPERATIONS SCIENTIFIC USERS $31.7 M ALMA CONSTRUCTION $11.9 M EVLA CONSTRUCTION A SUITE OF FOUR WORLDCLASS $0.7 M ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORIES EXTERNAL GRANTS $3.8 M NRAO FACTS & FIGURES $ 2 Contents DIRECTOR’S REPORT. 5 NRAO IN BRIEF . 6 SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS . 8 ALMA CONSTRUCTION. 26 OPERATIONS & DEVELOPMENT . 30 SCIENCE SUPPORT & RESEARCH . 58 TECHNOLOGY . 74 EDUCATION & PUBLIC OUTREACH. 80 MANAGEMENT TEAM & ORGANIZATION. 84 PERFORMANCE METRICS . 90 APPENDICES A. PUBLICATIONS . 94 B. EVENTS & MILESTONES . 118 C. ADVISORY COMMITTEES . .120 D. FINANCIAL SUMMARY . .124 E. MEDIA RELEASES . .126 F. ACRONYMS . .136 COVER: The National Radio Astronomy Observatory Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, located near Socorro, New Mexico, is a radio telescope of unprecedented sensitivity, frequency coverage, and imaging capability that was created by extensively modernizing the original Very Large Array that was dedicated in 1980. This major upgrade was completed on schedule and within budget in December 2012, and the Jansky Very Large Array entered full science operations in January 2013. The upgrade project was funded by the US National Science Foundation, with additional contributions from the National Research Council in Canada, and the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia in Mexico. Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF. LEFT: An international partnership between North America, Europe, East Asia, and the Republic of Chile, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) is the largest and highest priority project for the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, its parent organization, Associated Universities, Inc., and the National Science Foundation – Division of Astronomical Sciences. -

Astronomy Magazine 2020 Index

Astronomy Magazine 2020 Index SUBJECT A AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers), Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 Abell 21 (Medusa Nebula), 2:56, 59 Abell 85 (galaxy), 4:11 Abell 2384 (galaxy cluster), 9:12 Abell 3574 (galaxy cluster), 6:73 active galactic nuclei (AGNs). See black holes Aerojet Rocketdyne, 9:7 airglow, 6:73 al-Amal spaceprobe, 11:9 Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri) (star), binocular observation of, 1:62 Alnasl (Gamma Sagittarii) (optical double star), 8:68 Alpha Canum Venaticorum (Cor Caroli) (star), 4:66 Alpha Centauri A (star), 7:34–35 Alpha Centauri B (star), 7:34–35 Alpha Centauri (star system), 7:34 Alpha Orionis. See Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis) Alpha Scorpii (Antares) (star), 7:68, 10:11 Alpha Tauri (Aldebaran) (star), binocular observation of, 1:62 amateur astronomy AAVSO Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 beginner’s guides, 3:66, 12:58 brown dwarfs discovered by citizen scientists, 12:13 discovery and observation of exoplanets, 6:54–57 mindful observation, 11:14 Planetary Society awards, 5:13 satellite tracking, 2:62 women in astronomy clubs, 8:66, 9:64 Amateur Telescope Makers of Boston (ATMoB), 8:66 American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) binocular observations of, 12:60 consumption of dwarf galaxies, 2:11 images of, 3:72, 6:31 satellite galaxies, 11:62 Antares (Alpha Scorpii) (star), 7:68, 10:11 Antennae galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), 3:28 Apollo missions commemorative postage stamps, 11:54–55 extravehicular activity -

Appendix C Common Abbreviations & Acronyms

C Common Abbreviations and Acronyms Michael A. Strauss This glossary of abbreviations used in this book is not complete, but includes most of the more common terms, especially if they are used multiple times in the book. We split the list into general astrophysics terms and the names of various telescopic facilities and surveys. General Astrophysical and Scientific Terms • ΛCDM: The current “standard” model of cosmology, in which Cold Dark Matter (CDM) and a cosmological constant (designated “Λ”), together with a small amount of ordinary baryonic matter, together give a mass-energy density sufficient to make space flat. Sometimes written as “LCDM”. • AAAS: American Association for the Advancement of Science. • AAVSO: American Association of Variable Star Observers (http://www.aavso.org). • ADDGALS: An algorithm for assigning observable properties to simulated galaxies in an N-body simulation. • AGB: Asymptotic Giant Branch, referring to red giant stars with helium burning to carbon and oxygen in a shell. • AGN: Active Galactic Nucleus. • AM CVn: An AM Canum Venaticorum star, a cataclysmic variable star with a particularly short period. • AMR: Adaptive Mesh Refinement, referring to a method of gaining dynamic range in the resolution of an N-body simulation. • APT: Automatic Photometric Telescope, referring to small telescopes appropriate for pho- tometric follow-up of unusual variables discovered by LSST. • BAL: Broad Absorption Line, a feature seen in quasar spectra. • BAO: Baryon Acoustic Oscillation, a feature seen in the power spectra of the galaxy distri- bution and in the fluctuations of the Cosmic Microwave Background. • BBN: Big-Bang Nucleosynthesis, whereby deuterium, helium, and trace amounts of lithium were synthesized in the first minutes after the Big Bang. -

Annual Report 2014 C.Indd

2014 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL RADIO ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY 1 NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE 485 EMPLOYEES 51 MEDIA RELEASES 535 REFEREED SCIENCE PUBLICATIONS PROPOSAL AUTHORS FISCAL YEAR 2014 1425 – NRAO SEMESTER 2014B NRAO / ALMA OPERATIONS 1432 – NRAO SEMESTER 2015A $79.9 M 1500 – ALMA CYCLE 2, NA EXECUTIVE ALMA CONSTRUCTION $12.4 M EVLA CONSTRUCTION A SUITE OF FOUR $0.1 M WORLD-CLASS ASTRONOMICAL EXTERNAL GRANTS OBSERVATORIES $4.6 M NRAO FACTS & FIGURES $ 2 Contents DIRECTOR’S REPORT. .5 . NRAO IN BRIEF . 6 SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS . 8 ALMA CONSTRUCTION. 24. OPERATIONS & DEVELOPMENT . 28 SCIENCE SUPPORT & RESEARCH . 58 TECHNOLOGY . 74 EDUCATION & PUBLIC OUTREACH. 82 . MANAGEMENT TEAM & ORGANIZATION. .86 . PERFORMANCE METRICS . 94 APPENDICES A. PUBLICATIONS . 100. B. EVENTS & MILESTONES . .126 . C. ADVISORY COMMITTEES . 128 D. FINANCIAL SUMMARY . .132 . E. MEDIA RELEASES . 134 F. ACRONYMS . 148 COVER: An international partnership between North America, Europe, East Asia, and the Republic of Chile, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) is the largest and highest priority project for the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, its parent organization, Associated Universities, Inc., and the National Science Foundation – Division of Astronomical Sciences. Operating at an elevation of more than 5000m on the Chajnantor plateau in northern Chile, ALMA represents an enormous leap forward in the research capabilities of ground-based astronomy. ALMA science operations were initiated in October 2011, and this unique telescope system is already opening new scientific frontiers across numerous fields of astrophysics. Credit: C. Padillo, NRAO/AUI/NSF. LEFT: The National Radio Astronomy Observatory Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, located near Socorro, New Mexico, is a radio telescope of unprecedented sensitivity, frequency coverage, and imaging capability that was created by extensively modernizing the original Very Large Array that was dedicated in 1980. -

ASTR 1020 Homework Solutions

ASTR 1020 Homework Solutions Chapter 1 24. Set up a proportion, but be sure that you express all the distances in the same units (e.g., centimeters). The diameter of the Sun is to the size of a basketball as the distance to Proxima Centauri (4.2 LY) is to the unknown distance (X), so (1.4 × 1011 cm) / (30 cm) = (4.2 LY)(9.46 × 1017 cm/LY) / (X) Rearranging terms, we get X = (4.2 LY)(9.46 × 1017 cm/LY)(30 cm) / (1.4 × 1011 cm) = 8.51 × 108 cm = 8.51 × 103 km = 8510 km In other words, if the Sun were the size of a 30-cm diameter ball, the nearest star would be 8510 km away, which is roughly the distance from Los Angeles to Tokyo. 27. The Sun’s hydrogen mass is (3/4) × (1.99 × 1030 kg) = 1.49 × 1030 kg. Now divide the Sun’s hydrogen mass by the mass of one hydrogen atom to get the number of hydrogen atoms contained in the Sun: (1.49 × 1030 kg) / (1.67 × 10-27 kg/atom) = 8.92 × 1056 atoms. 8 11 29. The distance from the Sun to the Earth is 1 AU = 1.496 × 10 km = 1.496 × 10 m. The light-travel time is the distance, 1 AU, divided by the speed of light, i.e., 11 8 3 time = distance/speed = (1.496 × 10 m) / (3.00 × 10 m/s) = 0.499 × 10 s = 499 s = 8.3 minutes. 34. Since you are given diameter (D = 2.6 cm) and angle, and asked to find distance, you need to rewrite the small-angle formula as d = (206,265)(D) / (α). -

O Personenregister

O Personenregister A alle Zeichnungen von Sylvia Gerlach Abbe, Ernst (1840 – 1904) 100, 109 Ahnert, Paul Oswald (1897 – 1989) 624, 808 Airy, George Biddell (1801 – 1892) 1587 Aitken, Robert Grant (1864 – 1951) 1245, 1578 Alfvén, Hannes Olof Gösta (1908 – 1995) 716 Allen, James Alfred Van (1914 – 2006) 69, 714 Altenhoff, Wilhelm J. 421 Anderson, G. 1578 Antoniadi, Eugène Michel (1870 – 1944) 62 Antoniadis, John 1118 Aravamudan, S. 1578 Arend, Sylvain Julien Victor (1902 – 1992) 887 Argelander, Friedrich Wilhelm August (1799 – 1875) 1534, 1575 Aristarch von Samos (um −310 bis −230) 627, 951, 1536 Aristoteles (−383 bis −321) 1536 Augustus, Kaiser (−62 bis 14) 667 Abbildung O.1 Austin, Rodney R. D. 907 Friedrich W. Argelander B Baade, Wilhelm Heinrich Walter (1893 – 1960) 632, 994, 1001, 1535 Babcock, Horace Welcome (1912 – 2003) 395 Bahtinov, Pavel 186 Baier, G. 408 Baillaud, René (1885 – 1977) 1578 Ballauer, Jay R. (*1968) 1613 Ball, Sir Robert Stawell (1840 – 1913) 1578 Balmer, Johann Jokob (1825 – 1898) 701 Abbildung O.2 Bappu, Manali Kallat Vainu (1927 – 1982) 635 Aristoteles Barlow, Peter (1776 – 1862) 112, 114, 1538 Bartels, Julius (1899 – 1964) 715 Bath, KarlLudwig 104 Bayer, Johann (1572 – 1625) 1575 Becker, Wilhelm (1907 – 1996) 606 Bekenstein, Jacob David (*1947) 679, 1421 Belopolski, Aristarch Apollonowitsch (1854 – 1934) 1534 Benzenberg, Johann Friedrich (1777 – 1846) 910, 1536 Bergh, Sidney van den (*1929) 1166, 1576, 1578 Bertone, Gianfranco 1423 Bessel, Friedrich Wilhelm (1784 – 1846) 628, 630, 1534 Bethe, Hans Albrecht (1906 – 2005) 994, 1010, 1535 Binnewies, Stefan (*1960) 1613 Blandford, Roger David (*1949) 723, 727 Blazhko, Sergei Nikolajewitsch (1870 – 1956) 1293 Blome, HansJoachim 1523 Bobrovnikoff, Nicholas T. -

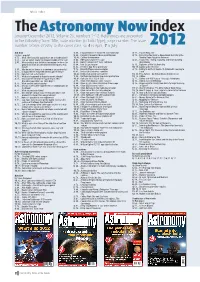

Astronomy Now the Index

Article index The Astronomy Nowindex January–December 2012, Volume 26, numbers 1–12. References are presented in the following form: Title, issue number (in bold type), page number. The issue number relates directly to the cover date, so 4 is April, 7 is July. 2012 Ask Alan 1; 86 Farpoint two-inch enhanced auto-collimator 7; 72 Elusive Wow, The By Alan Longstaff 5; 84 Farpoint U mount medium parallelogram 9; 78 Everything You Need to Know About Everything You 1; 75 What effect would a quasar have on a nearby planet? 12; 83 Galilean thermometer Need to Know About the Universe 1; 75 Can we detect Jupiter by Doppler wobble of the Sun? 4; 84 HM5 polar alignment scope 4; 80 Exoplanets: Finding, Exploring and Understanding 2; 65 When relativity was tested by comparing clocks on the 8; 84 Hotech advanced CT laser collimator Alien Worlds ground and in an aircraft what time discrepancy was 5; 84 Istar 25 pro focuser 2; 72 Explorers of the Southern Sky found? 6; 82 Kendrick Digi-Klear pad heater 10; 79 Exploring the Universe 2; 65 Why do we see Venus as a morning or an evening star? 7; 72 Magnifi iPhone camera adaptor 2; 72 Falling to Earth: An Apollo 15 Astronaut’s Journey to 3; 73 Is it possible to image the Ashen Light of Venus? 6; 82 Nexus GOTO wireless controller Earth 3; 73 How fast can a star rotate? 12; 82 Nightstreak green laser pointer 11; 80 Fritz Zwicky – An Extraordinary Astrophysicist 4; 75 Whatever happened to Hagen’s cosmic clouds? 1; 86 Northern Hemisphere two-sided planisphere 12; 78 Galileo 4; 75 Who was the Astronomer Royal -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism.