Nonviolent Leadership: a Concept Whose Time Has Passed?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist who The Reverend became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King Martin Luther King Jr. advanced civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist Martin Luther King Sr. King participated in and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.[1] King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with some success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were several dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.[2] FBI King in 1964 Director J. Edgar Hoover considered King a radical and made him an 1st President of the Southern Christian object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963, forward. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital Leadership Conference affairs and reported on them to government officials, and, in 1964, In office mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.[3] January 10, 1957 – April 4, 1968 On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating Preceded by Position established racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. -

Broadway Musical Performed By

“I HAVE A DREAM” BROADWAY MUSICAL PERFORMED BY PRESENTED BY MATSU MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. FOUNDATION September 24-27, 2020 at the Glenn Massay Theater FOR TICKETS: CALL 907.746.9300 OR VISIT GLENNMASSAYTHEATER.COM STUDENTS: $5.00 SENIORS/VETERANS: $7.00 GENERAL ADMISSION: $25.00 GALA NIGHT: $65.00 PRESS RELEASE – May 2020 Herman LeVern Jones’ TheatreSouth (TSA) is thrilled to tour “I Have A Dream” the Broadway Musical to the MatSu area, presented by the MatSu Martin Luther King, Jr. Foundation! The performances will feature residents (with a focus on youth) from the MatSu and surrounding communities as actors, singers, dancers and musicians. The performers will go through an intensive rehearsal process that will involve theory, history, script analysis, acting coaching and open discussions about the Civil Rights Movement and its impact on life in the United States today. There are also opportunities for behind-the-scenes involvement in the areas of stage management, lighting/sound/set design, costuming, hair and make-up. "I Have A Dream" is a gospel musical on the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. that chronicles the major events of the Civil Rights Movement from December 1, 1955 when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a White person up to the assassination of Dr. King on April 4, 1968. This depiction of Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement gives tremendous insight into Dr. King's love of his family, his sense of humor, and the incredible sacrifices that Americans made in the fight for racial equality. The production is a compilation of 28 Gospel songs/parts of songs from the Civil Rights Movement such as We Shall Over Come, We Shall Not Be Moved, His Eye is on the Sparrow, Precious Lord Take My Hand, Anybody Here Seen My Old Friend Martin and the Negro National Anthem, Lift Every Voice and Sing! There are 125+ slides of Dr. -

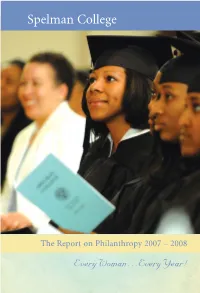

The Report on Philanthropy 2007 – 2008 Every Woman…Every Year!

Spelman College The Report on Philanthropy 2007 – 2008 Every Woman…Every Year! A Message from the President Greetings: This publication celebrates the philanthropic spirit of our benefactors and affords me the opportunity to express my sincere thanks to our alumnae, trustees, faculty, staff, parents, students and friends for supporting Spelman College. Every gift, whether large or small, has a meaningful impact on the College, and ensures our position among the nation’s foremost liberal arts and women’s colleges. A major point of pride is alumnae support. The number of alumnae donors grew to more than 4,000 contributors, or 30% of all alumnae. The number of student donors and the amount they gave to the College more than tripled. Gifts from parents increased by 50 percent. More than 46 percent of Spelman faculty and staff were also donors last year, a testament to their outstanding commitment to the College and our students. Spelman is a privately funded college, so your gifts provide resources that help bridge the chasm that separates good colleges from truly great ones. We take enormous pride in Spelman’s legacy of providing a superior educational experience for women of African descent, and remain committed to the principles of academic excellence, leadership development, service learning and social transformation. Your support helps to ensure our ability to provide scholarships, recruit the brightest students and faculty, afford technological enhancements and campus improvements, and deliver the curricular and co-curricular support necessary to educate and nurture women who are making the choice to change the world. With a nearly 80 percent graduation rate, Spelman continues to be recognized by such rating entities as US News & World Report, Princeton Review and The Chronicle of Higher Education as one of the best liberal arts colleges in the country. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X: Search for the Direction of the Civil Rights Movement Master’s Thesis Brno 2019 Supervisor: Author: Michael George, M.A. Bc. Michaela Procházková I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this master’s thesis and that I have not used any sources other than those identified as references. Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. Brno, 25. 3. 2019 Bc. Michaela Procházková Acknowledgment I would like to thank my supervisor, Michael George, M.A., for his time, help, guidance, patience and advice. Also, I would like to thank Erick Daniel Worthington. Last, I would like to thank my parents and family for their support. Annotation This master’s thesis discusses lives of two African American activists, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, in the United States of America. Their lives are described from their childhood and then the main emphasis is put on their involvement in the Civil Rights Movement which later turned to the Black Power movement. In the last part of the thesis, elements of the similarity of these two African American leaders are examined. Key words Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Civil Rights Movement, Black Power movement Anotace Tato diplomová práce se zabývá životy dvou afroamerických aktivistů, Martinem Lutherem Kingem, Jr. -

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King Resource 2021 1 January, 2021 Dear Beloved Community “And one of the great liabilities of life is that all too many people find themselves living amid a great period of social change, and yet they fail to develop the new attitudes, the new mental responses, that the new situation demands.” — Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The wisdom of these words resonated deeply as we are in the midst of multiple pandemics. Our world has been called into doing things we’ve never had to do. But in the midst of it all, the love of Jesus Christ always comes through. We have also been reminded of the importance of the beloved community. This community that may be meeting virtually and not physically with each other. Yet the physical distance doesn’t mean that we are disconnected from each other. We have learned that social distancing doesn’t mean social disconnection. Dr. King’s words are timeless and often apply to what we are presently experiencing. As we celebrate his life and legacy, remember his commitment to beloved community. Remember his commitment to justice. Remember his commitment to speaking on behalf of the marginalized and oppressed. Re- member his courage to speak truth to power. You are encouraged to use these resources not only during the month of his celebration, but throughout the year. We are grateful for his legacy. Blessings, Rev. Sheila P. Spencer Rev. Sheila P. Spencer Interim President, Disciples Home Missions Director of Christian Education and Faith Formation Disciples Home Missions PO Box 1986, Indianapolis, IN 46206-1986 317-713-2634 [email protected] 2 Scripture Reference Genesis 37:18-20 Matthew 5:44 They saw him in the distance, and before But I say unto you. -

Download Coordinate Picture of Martin Luther King Epub

Site Navigation Deutsch Enter Search Coordinate picture of Jay A. Brown, courtesy of the Brown family. In April 1963, King martin luther king and the SCLC joined Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of the Alabama 16 First Avenue Christian Movement for Human Rights in a nonviolent campaign Haskell, NJ 07420 USA to end segregation and force Birmingham, Alabama, businesses 973-248-8080 to hire Black people. Fire hoses and vicious dogs were unleashed Fax: 973-248-8012 on the protesters by "Bull" Connor's police officers. King was [email protected] thrown into jail. King spent eight days in the Birmingham jail as a [email protected] result of this arrest but used the time to write "Letter From a Birmingham Jail," affirming his peaceful philosophy. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial located in Washington, DC Washington, United States - August 18, 2014: People meander about the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in West Potomac Park, southwest of the National Mall, during the nighttime. The memorial honors civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968) and was sculpted by Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin (born 1954). photos of martin luther king stock pictures, royalty-free photos & images. T he daughter of a former political aide had no idea she had a piece of history sitting in a drawer. Flight Distance Calculator " Need to know the distances between two cities by airplane?. The latitude for 2150 Dr Martin Luther King Jr Blvd, Bronx, NY 10453, USA is: 40.857454 and the longitude is: -73.909306. Coretta Scott King and her four TEENren view Martin Luther King's body in Atlanta on April 7, 1968. -

THE NUBIAN MESSAGE Tile Fllfi'ifian

." MESSAGE THE NUBIAN 1 I Tile fllfi‘ifian-fllmerican rVoice offlortfi Carofina State University 51,7:,‘Yo'ljgiume 4, Edition 9 , Established in 1992 January 25, 1996 Yolanda King Heads Up The Martin Luther King Festivities B Fred Frazier News Editor Theatre. She is also the co—founder This was a celebration of what actively on college campuses for with Attallah Shabazz of NUCLE- would have been the 67th birthday change throughout America, but News US. NUCLEUS is a company of of Martin Luther King, Jr. At the they are small in number. And over- As a culmination of the Martin performing artists dedicated --Yolanda King Heads Up to pro- McKimmon Center the theme of the looked by the sheer abundance of Luther King, Jr. festivities this past moting positive energy through the festival, “Living the Dream: MLK Festivities apathetic students, who are either weekend, the eldest child of Dr. and arts. Empowering the Community and standing on the sideline and watch- --Changes in Guidelines Mrs. King, Yolanda King, was Involving Our Children to Make a ing or are uninformed of what’s for Resident Advisors scheduled to speak at a dinner hon- Difference,” was in full effect. going on. oring cover story her father. There were lots of children and She also discussed the need for As far as a profession goes, Ms. many people present that afternoon economic empowerment in the King wears many hats. She is an from the surrounding communities. Black community. Because of the --Course Repeat Policy actress, a producer-director, and a There were many activities going on disparity between the races econom- Revamped lecturer. -

Yolanda King to Lead UNH Celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr Day

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Media Relations UNH Publications and Documents 1-26-2000 Yolanda King To Lead UNH Celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr Day Michelle Gregoire UNH Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/news Recommended Citation Gregoire, Michelle, "Yolanda King To Lead UNH Celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr Day" (2000). UNH Today. 2674. https://scholars.unh.edu/news/2674 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNH Publications and Documents at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Relations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yolanda King To Lead UNH Celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day 11/29/17, 1139 AM Yolanda King To Lead UNH Celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day By Michelle Gregoire UNH News Bureau DURHAM, N.H. -- Yolanda King will be the keynote speaker at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebration at the University of New Hampshire Sunday, Jan. 30. The eldest daughter of the slain civil rights leader, Yolanda King is a rousing speaker and accomplished actress who has committed her talents to affecting social and personal change. The celebration, which is free and open to the public, will begin at the UNH Field House at 3 p.m. Afterward, there will be a candlelight march to the Memorial Union Building, where a reception will be held in the Strafford Room. -

Answers to Activity Sheets for Grades 4 Through 8

Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site Visitor Center Exhibits Answers to Activity Sheets for Grades 4 through 8 SEGREGATION Define the word Segregation? The separation or isolation of a race, class or ethnic group by enforced or voluntary residence in a restricted area by barriers to social intercourse. 1. Give three examples of segregation? A. Separate bathrooms B. Separate water fountains C. Separate Schools D. Non-example: Answers will vary. 2. Look at the pictures of schools of the 1930’s (black school on the left, white school on the right). How are they different on the outside? Wood vs. Brick Small vs. Large How do you think they were different on the inside? (heat, lights, books, supplies, etc.)? No central heating, limited supplies, and outdated textbooks (The photo underneath will help you answer the question). 261 3. What were Jim Crow Laws? Jim Crow Laws were State segregation laws enacted to keep the black and white races separate. List 3 that might have affected you if you lived in the 1930s or 1940s. No colored barbers shall serve as a barber to white women and girls. Books shall not be interchangeable between the white and colored schools. But should continue to be used by the race first using them. (NC) The state librarian is directed to fit up and maintain a separate place for the use of the colored people who may come to the library for the purpose of reading books or periodicals. (NC) 4. Watch the video in this area. What happened at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957? Nine students integrated Central High School. -

Compiled by the Staff of the Office of Student Ac I S and Leadership

Civil Rights Landmarks Display Compiled by the staff of the Office of Student Ac9vi9es and Leadership Development, Wesleyan University Slavery in North America 1654-June 19, 1865? Four hundred years ago, in 1607, Jamestown, VA, the first permanent seKlement by Europeans in North America was founded. In 1610, John Rolfe introduced a strain of tobacco which Quickly became the colony’s economic foundaon. By 1619, more labor was needed to support the tobacco trade and “indentured servants” were brought to the colony including about 20 Africans. As of 1650, there were about 300 "Africans" living in Virginia, about 1% of an es9mated 30,000 populaon. They were s9ll not slaves, and they joined approximately 4000 white indentured "servants" working out their loans for passage money to Virginia. They were granted 50 acres each when freed from their indentures, so they could raise their own tobacco. Slavery was brought to North America in 1654, when Anthony Johnson, in Northampton County, convinced the court that he was en9tled to the life9me services of John Casor, a Black man. This was the first judicial approval of life servitude, except as punishment for a crime. Anthony Johnson was a Black man, one of the original 20 brought to Jamestown in 1619. By 1623, he had achieved his freedom and by 1651 was prosperous enough to import five "servants" of his own, for which he was granted 250 acres as "headrights". However, the Transatlan9c slave trade from Africa to the Americas had been around for over a century already, originang around 1500, during the early period of European discovery of West Africa and the establishment of Atlan9c colonies in the Caribbean and South and North America when growing sugar cane (and a few other crops) was found to be a lucrave enterprise. -

The Mustang Messenger

- The Mustang Messenger 2nd Edition Martin Luther King Jr. Coronavirus By: Payton by: Etta Early Life Martin Luther King Jr. was born on January 15th, 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia. He was the youngest sibling. His siblings' names were Christine King Farris, and Alfred Daniel Williams King. His mothers name was Alberta Williams King. His mother was the organizer and president of the Ebenezer Women's Committee, she was also a choir organist at Ebenezer. His father was a preacher, a baptist , and a missionary early figure in civil rights movements. Martin’s wife was named Coretta Scott King and their kids' names were, Martin Luther King III, Yolanda King, Dexter King, and Do you know that COVID 19 is Bernice King. spreading a lot? Well here are some Martin’s white friends had to go to a different school from his, and once the facts about COVID 19. One fact is that school year started their parents stopped letting King come over and play. His according to the CDC, getting the mother explained to him the history of slavery and segregation. The schools he vaccine will help in not getting COVID 19. went to were, School of Theology, Crozer Theological Seminary, Morehouse College, Another fact is according to the CDC, Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, Boston University, and Booker T. there are 31,161,075 vaccine shots out in Washington High School. He was not rich although his family was. He was an total. American Baptist pastor and a civil rights leader. He traveled a lot due to that Those are some facts about matter. -

The 21St ANNUAL

The 22nd ANNUAL Dr. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. HOLIDAY in Hawai’I Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Coalition-Hawaii www.mlk-hawaii.com 1988-2010 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Coalition – Hawai`i 2010 Officers: Patricia Anthony . .President Scott Foster . 1st Vice President Juliet Begley . Secretary William Rushing . Treasure Co-Sponsor: City & County of Honolulu, Event Chairs: Candlelight Bell Ringing Ceremony: Marsha Joyner & Rev. Charlene Zuill Parade Chairs: William Rushing & Pat Anthony Unity Rally: Jewell McDonald Vendors: Derek Tamura Webmaster: Scott Foster Coalition Support Groups: African American Association Hawaii Government Employees Association Hawaii National Guard Hawaii State AFL-CIO Hawaiian National Communications Corporation Headquarters US Pacific Command ‘Olelo: The Corporation for Community Television Kappa Alpha Phi Fraternity Self Management Corporation State of Hawai`i United Nations Association of Hawaii – Hawaii Division United States Military University of Hawaii Professional Assembly Booklet Editor: MarshaRose Joyner Copyright: Hawaiian National Communications Corporation, 2010. All rights reserved. 2 Table of Contents Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Coalition – Hawai`i 2010........................................... 2 Candlelight Bell Ringing Ceremony................................................................... 6 Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba..................................................................................... 7 Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday Unity Rally..................................................