Identifying Geospatial Signatures of Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb Abstract Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Des Medecins Specialists

LISTE DES MEDECINS SPECIALISTS N° NOM PRENOM SPECIALITE ADRESSE ACTUELLE COMMUNE 1 MATOUK MOHAMED MEDECINE INTERNE 130 LOGTS LSP BT14 PORTE 122 BAGHLIA 2 DAFAL NADIA OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE EL LOUZ VILLA N° 24 BENI AMRANE 3 HATEM AMEL GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE RUE CHAALAL MED LOT 02 1ERE ETAGE BENI AMRANE 4 BERKANE FOUAD PEDIATRIE RUE BOUIRI BOUALELM BT 01 N°02 BOR DJ MENAIEL 5 AL SABEGH MOHAMED NIDAL UROLOGIE RUE KHETAB AMAR , BT 03 , 1ER ETAGE BORDJ MENAIEL 6 ALLAB OMAR OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE 250 LOGTS, BT N ,CAGE 01 , N° 237 BORDJ MENAIEL 7 AMNACHE OMAR PSYCHIATRIE CITE 96 LOGTS , BT 03 BORDJ MENAIEL 8 BENMOUSSA HOCINE OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE MADAOUI ALI , BT 08, 1ER ETAGE BORDJ MENAIEL 9 BERRAZOUANE YOUCEF RADIOLOGIE CITE ELHORIA ,LOGTS N°03 BORDJ MENAIEL 10 BOUCHEKIR BADIA GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE CITE DES 250 LOGTS, N° 04 BORDJ MENAIEL 11 BOUDJELLAL MOHAMMED OUALI GASTRO ENTEROLOGIE CITE DES 92 LOGTS, BT 03, N° 01 BORDJ MENAIEL 12 BOUDJELLAL HAMID OPHTALMOLOGIE BORDJ MENAIEL BORDJ MENAIEL 13 BOUHAMADOUCHE HAMIDA GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE RUE AKROUM ABDELKADER BORDJ MENAIEL 14 CHIBANI EPS BOUDJELLI CHAFIKA MEDECINE INTERNE ZONE URBAINE II LOT 55 BORDJ MENAIEL 15 DERRRIDJ HENNI RADIOLOGIE COPPERATIVE IMMOBILIERE EL MAGHREB ALARABI BORDJ MENAIEL 16 DJEMATENE AISSA PNEUMO- PHTISIOLOGIE CITE 24 LOGTS BTB8 N°12 BORDJ MENAIEL 17 GOURARI NOURREDDINE MEDECINE INTERNE RUE MADAOUI ALI ECOLE BACHIR EL IBRAHIMI BT 02 BORDJ MENAIEL 18 HANNACHI YOUCEF ORL CITE DES 250 LOGTS BT 31 BORDJ MENAIEL 19 HUSSAIN ASMA MEDECINE INTERNE 78 RUE KHETTAB AMAR BORDJ MENAIEL 20 -

Kurzübersicht Über Vorfälle Aus Dem Armed Conflict Location & Event

ALGERIA, FIRST QUARTER 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 22 June 2017 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, 3 June 2017; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from March 2015 Conflict incidents by category to March 2017 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 130 1 battle 18 48 strategic developments 7 0 remote violence 4 2 violence against civilians 4 2 total 163 53 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, 3 June 2017). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, January 2017, and ACLED, 3 June 2017). ALGERIA, FIRST QUARTER 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 22 JUNE 2017 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Adrar, 2 incidents killing 0 people were reported. The following location was affected: Adrar. In Alger, 11 incidents killing 0 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Algiers, Bab El Oued, Baba Ali, Mahelma. -

Completion Report (Algeria)

Annex 5 Attempts and Lessons Learned Annex 5-1 Implementation of provision of Executive Decree 07-299 and 07-300, September 17, 2007 Annex 5-1 Implementation of provision of Executive Decree 07-299 and 07-300, September 17, 2007 REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L' AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITO IRE ET DE L'ENVIRONNE:MENT Observatoire National de l'Environnement ~ ~)I .l-p.,-JI et du Developpement Durable L...41.h.. JI:i .4·~ II.J O.N.E.D.D DIRECTION GENERALE Ref. : 360 IDG/ONEDD Alger, Ie o 6 DEC 2.010 Messieurs les Directeurs de laboratoires H!gionaux Mesdames et Messieurs les chefs de stations de surveillance. Objet: AlS mise en ceuvre des dispositions des decrets executifs 07-299 et 07-300 du 17 septembre 2007. Ref : Lettre, nO 3701 SPIvfJ 10 du 28 novembre 2010 de Monsieur]e Ministre. En application des instructions de Monsieur Ie Ministre relatives a la mise en ceuvre des dispositions des decrets executifs cites en objet; J'ai l'honneur de vous transmettre ci- joint une procedure des modalites pratiques pour l' organisation du travail dans Ie cadre de cette mission. D'autre part, des seances de travail seront programmees, au courant du mois de decembre 2010 etjanvier 20 Hpour une meilleure maitrise de l' organisation territoriale a mettre en place et la methode de prise en charge de cette tache en fonction de nos capacites materielles et humaines. Aussi, je vous invite a entamer d'ores et deja, des discussions sur les v5>ies et moyens amettre en ceuvre pour accomplir cette mission dans les meilleur&s conditions, avec les ingenieurs de vas structures respectives et de me transmettre les comptes rendus. -

Journal Officiel Algérie

° N 30 Dimanche 15 Safar 1423 41è ANNEE correspondant au 28 avril 2002 JJOOUURRNNAALL OOFFFFIICCIIEELL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE CONVENTIONS ET ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX - LOIS ET DECRETS ARRETES, DECISIONS, AVIS, COMMUNICATIONS ET ANNONCES (TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE) DIRECTION ET REDACTION: Algérie ETRANGER Tunisie SECRETARIAT GENERAL ABONNEMENT Maroc DU GOUVERNEMENT (Pays autres ANNUEL Libye que le Maghreb) WWW. JORADP. DZ Mauritanie Abonnement et publicité: IMPRIMERIE OFFICIELLE 1 An 1 An 7,9 et 13 Av. A. Benbarek-ALGER Tél: 65.18.15 à 17 - C.C.P. 3200-50 Edition originale….........…............…… 1070,00 D.A 2675,00 D.A ALGER TELEX : 65 180 IMPOF DZ BADR: 060.300.0007 68/KG Edition originale et sa traduction......... 2140,00 D.A 5350,00 D.A ETRANGER: (Compte devises) (Frais d'expédition en sus) BADR: 060.320.0600 12 Edition originale, le numéro : 13,50 dinars. Edition originale et sa traduction, le numéro : 27,00 dinars. Numéros des années antérieures : suivant barème. Les tables sont fournies gratuitement aux abonnés. Prière de joindre la dernière bande pour renouvellement, réclamation, et changement d'adresse. Tarif des insertions : 60,00 dinars la ligne ° 15 Safar 1423 2 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE N 30 28 avril 2002 S O M M A I R E DECISIONS INDIVIDUELLES Décret présidentiel du 18 Moharram 1423 correspondant au 1er avril 2002 mettant fin aux fonctions du directeur de la planification et de l'aménagement du territoire à la wilaya de Tlemcen..................................................................................... 5 Décret présidentiel du 18 Moharram 1423 correspondant au 1er avril 2002 mettant fin aux fonctions du directeur des transports à la wilaya d'El Bayadh................................................................................................................................................................. -

ALGERIEN, JAHR 2012: Kurzübersicht Über Vorfälle Aus Dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Zusammengestellt Von ACCORD, 3

ALGERIEN, JAHR 2012: Kurzübersicht über Vorfälle aus dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) zusammengestellt von ACCORD, 3. November 2016 Staatsgrenzen: GADM, November 2015b; Verwaltungsgliederung: GADM, November 2015a; Vor- fallsdaten: ACLED, ohne Datum; Küstenlinien und Binnengewässer: Smith und Wessel, 1. Mai 2015 Konfliktvorfälle je Kategorie Entwicklung von Konfliktvorfällen von 2003 bis 2012 Kategorie Anzahl der Vorfälle Summe der Todesfälle Ausschreitungen/Proteste 80 6 Kämpfe 73 214 strategische 40 2 Entwicklungen Fernangriffe 30 23 Gewalt gegen 11 3 Zivilpersonen gesamt 234 248 Das Diagramm basiert auf Daten des Armed Conflict Location & Event Die Tabelle basiert auf Daten des Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project Data Project (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, ohne Datum). (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, ohne Datum) ALGERIEN, JAHR 2012: KURZÜBERSICHT ÜBER VORFÄLLE AUS DEM ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) ZUSAMMENGESTELLT VON ACCORD, 3. NOVEMBER 2016 LOKALISIERUNG DER KONFLIKTVORFÄLLE Hinweis: Die folgende Liste stellt einen Überblick über Ereignisse aus den ACLED-Datensätzen dar. Die Datensätze selbst enthalten weitere Details (Ortsangaben, Datum, Art, beteiligte AkteurInnen, Quellen, etc.). In der Liste werden für die Orte die Namen in der Schreibweise von ACLED verwendet, für die Verwaltungseinheiten jedoch jene der GADM-Daten, auf welchen die Karte basiert (in beiden Fällen handelt es sich ggf. um englische Transkriptionen). In Adrar wurden 10 Vorfälle mit 21 Toten erfasst, an folgenden Orten: Adrar, Bordj Badji Mokhtar, Bouassi, Tiliouine, Timiaouine, Timimoun. In Alger wurden 40 Vorfälle mit 11 Toten erfasst, an folgenden Orten: Algiers, Bab El Oued, Bachdjerrah, Baraki, Belouizdad, Bourouba, Cheraga, Dely Ibrahim, El Madania, Kouba, Place du 1er Mai, Sidi Moussa, Telemly, Tessala El Merdja. -

Plan Développement Réseau Transport Gaz Du GR TG 2017 -2027 En Date

Plan de développement du Réseau de Transportdu Gaz 2014-2024 N°901- PDG/2017 N°480- DOSG/2017 CA N°03/2017 - N°021/CA/2017 Mai 2017 Plan de développement du Réseau de Transport du Gaz 2017-2027 Sommaire INTRODUCTION I. SYNTHESE DU PLAN DE DEVELOPPEMENT I.1. Synthèse physique des ouvrages I.2. Synthèse de la valorisation de l’ensemble des ouvrages II. PROGRAMME DE DEVELOPPEMENT DES RESEAUX GAZ II.1. Ouvrages mis en gaz en 201 6 II.2. Ouvrages alimentant la Wilaya de Tamanrasset et Djanet II.3. Ouvrages Infrastructurels liés à l’approvisionnement en gaz nature l II.4. Ouvrages liés au Gazoduc Rocade Est -Ouest (GREO) II.5. Ouvrages liés à la Production d’Electricité II.6. Ouvrages liés aux Raccordement de la C lientèle Industrielle Nouvelle II.7. Ouvrages liés aux Distributions Publiques du gaz II .8. Ouvrages gaz à réhabiliter II. 9. Ouvrages à inspecter II. 10 . Plan Infrastructure II.1 1. Dotation par équipement du Centre National de surveillance II.12 . Prévisions d’acquisition d'équipements pour les besoins d'exploitation II.13 .Travaux de déviation des gazoducs Haute Pression II.1 4. Ouvrages en idée de projet non décidés III. BILAN 2005 – 201 6 ET PERSPECTIVES 201 7 -202 7 III.1. Evolution du transit sur la période 2005 -2026 III.2. Historique et perspectives de développement du ré seau sur la période 2005 – 202 7 ANNEXES Annexe 1 : Ouvrages mis en gaz en 201 6 Annexe 2 : Distributions Publiques gaz en cours de réalisation Annexe 3 : Distributions Publiques gaz non entamées Annexe 4 : Renforcements de la capacité des postes DP gaz Annexe 5 : Point de situation sur le RAR au 30/04/2017 Annexe 6 : Fibre optique sur gazoducs REFERENCE Page 2 Plan de développement du Réseau de Transport du Gaz 2017-2027 INTRODUCTION : Ce document a pour objet de donner le programme de développement du réseau du transport de gaz naturel par canalisations de la Société Algérienne de Gestion du Réseau de Transport du Gaz (GRTG) sur la période 2017-2027. -

Liste Des Societe D'expertise Et Experts Agrees Par L'uar "Boumerdes"

01, Lot Said HAMDINE, Bir Mourad Rais, - Alger - BP 226 CP 16033, ALGER. Tél. : (213) (0) 21 54 74 96 & 98 Fax : (213) (0) 21 54 69 22 Site Web : www.uar.dz - e-mail : [email protected] Association régie par l’ordonnance 95/07 du 25/01/1995 modifiée et complétée. LISTE DES SOCIETE D'EXPERTISE ET EXPERTS AGREES PAR L'UAR "BOUMERDES" Date N° Nom et Prénom Adresse Professionnelle Spécialité Tel. Mobile Fax E-Mail d'inscription Sarl Atlantic Entrepôts et Magasins Cité Benadjel, Section 09, Ilot N° 21, Facultés maritimes (021) 79 11 01 (0556) 662 423 1 31/07/2012 Généraux Boudouaou, Boumerdés Eurl Oum Darman Entrepôt Haouche Barak, N° 3, Khemis (024) 87 14 76 (0555) 911 453 (024) 87 14 78 [email protected] 2 14/07/2014 Khechna, Boumerdés Facultés Maritimes SARL BUREAU EXPERTECH Centre Commercial, Oued Tatarik, (021) 40 20 27 (0674) 782 729 [email protected] 3 24/04/2016 N° 14, Boumerdés Travaux Publics TEBBAKH El-Hadi Cité Frantz Fanon, 350 logts, Bt 5, Bâtiment (024) 81 98 93 4 29/11/1998 Appt N° 3, Boumerdès LOUBAR Belaid Cité du 11 Décembre 1960, Bt 17, N° Bâtiment 5 27/01/2005 02, Boumerdès 6 DJENADI Brahim 56, Cité 2, Béni-Amrane, Boumerdès Bâtiment 22/05/2005 (024) 87 23 08 (0770) 459 988 AIT MOKHTAR Rachid Said Haouch El-Mekhfi, Ouled-Heddadj, Bâtiment (0550) 812 259 7 26/12/2005 Boumerdès BOUAOUINA née HADJ CHERIF Plateau Boudouaou El-Bahri, Bâtiment (0662) 033 673 8 15/07/2007 Faïza Boumerdès HAICHOUR Karim Cité 11 décembre 1960, Coopérative Bâtiment (0772) 646 677 9 26/09/2011 El Azhar, N° 02, Boumerdès BOUTOUTAOU Bachir 01, Rue Ali Khodja, Tidjelabine, Bâtiment (024) 81 12 60 10 20/07/1999 Boumerdès ADNANE Hocine 10/C, Cité du 11 Décembre 1960, Bâtiment (024) 81 67 25 (0661) 612 874 (024) 81 67 25 11 Coop immobilière, El Balbala, 02/06/1998 Boumerdès BOUMARAF Miloud Cité des 351 logts, Bt 03, N° 06, Bâtiment (024) 81 67 26 12 05/08/2002 Boumerdès ROUIDJALI Réda Cité Chateau d`Eau, Villa N° 28, Bâtiment (024) 81 90 02 13 30/01/2001 Boumerdès Date N° Nom et Prénom Adresse Professionnelle Spécialité Tel. -

Terrorism in North Africa and the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach and Implications

TTeerrrroorriissmm iinn NNoorrtthh AAffrriiccaa && tthhee SSaahheell iinn 22001122:: GGlloobbaall RReeaacchh && IImmpplliiccaattiioonnss Yonah Alexander SSppeecciiaall UUppddaattee RReeppoorrtt FEBRUAR Y 2013 Terrorism in North Africa & the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach & Implications Yonah Alexander Director, Inter-University Center for Terrorism Studies, and Senior Fellow, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies February 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Yonah Alexander. Published by the International Center for Terrorism Studies at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced, stored or distributed without the prior written consent of the copyright holder. Manufactured in the United States of America INTER-UNIVERSITY CENTER FO R TERRORISM STUDIES Potomac Institute For Policy Studies 901 North Stuart Street Suite 200 Arlington, VA 22203 E-mail: [email protected] Tel. 703-525-0770 [email protected] www.potomacinstitute.org Terrorism in North Africa and the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach and Implications Terrorism in North Africa & the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach & Implications Table of Contents MAP-GRAPHIC: NEW TERRORISM HOTSPOT ........................................................ 2 PREFACE: TERRORISM IN NORTH AFRICA & THE SAHEL .................................... 3 PREFACE ........................................................................................................ 3 MAP-CHART: TERRORIST ATTACKS IN REGION SINCE 9/11 ....................... 3 SELECTED RECOMMENDATIONS -

022.Qxp (Page 1)

Au 2e jour de sa visite à la 3e Région militaire Gaïd Salah : «Le mois de mars marqué par les hauts faits aux objectifs nobles du peuple» Lors du deuxième jour de sa visite en 3e Région militaire à Béchar, le général de corps d’armée, Ahmed Gaïd Salah, vice-ministre de la Défense nationale, chef d’état-major de l’Armée nationale populaire a poursuivi l’inspection de quelques unités déployées dans le territoire du Secteur opérationnel sud de Tindouf, et supervisé l’exécution d’un exercice de tirs avec munitions réelles... Lire page 4 INFORMER ET PENSER LIBREMENT Quotidien National d’Information - 8e Année - Mercredi 20 mars 2019 - 13 Radjab 1440 - N° 2048 - Algérie : 10 DA / 1 € www.lechodalgerie-dz.com Marches populaires Les étudiants et les médecins marchent en force dans plusieurs villes du pays © uidoum G ateh F Lire page 5 Lire Photo : Lamamra l’a affirmé, hier, à Moscou : «Le Président Bouteflika est prêt à transmettre le pouvoir» Le président de la République, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, qui a décidé de ne pas se présenter à la prochaine élection présidentielle, s’est dit «prêt à transmettre le pouvoir de manière ouverte et transparente au président qui sera choisi par le scrutin», a déclaré le vice-Premier ministre, ministre des Affaires étrangères, Ramtane Lamamra... Lire page 3 www. lechodalgerie-dz. com www. lechodalgerie-dz.com 2 Echos d u jour Rallye Tuareg Chlef à El Ouata Décès Un réseau régional spécialisé d’un pilote italien Un pilote Italien dans le vol de véhicules neutralisé participant au rallye Tuareg est décédé à la Un réseau criminel spécialisé dans le vol Les deux suspects furent retrouvés en un suite d’un grave de véhicules dans la wilaya de Chlef et temps record, après qu’ils aient essayé de accident de son quad, nombre de wilayas avoisinantes, a été se cacher à proximité d’un oued, à 2 km hier, dans la région mis hors d’état de nuire par le du lieu où ils ont abandonné le véhicule d’El Ouata, a-t-on groupement territorial de la Gendarmerie volé. -

ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 7 November 2016

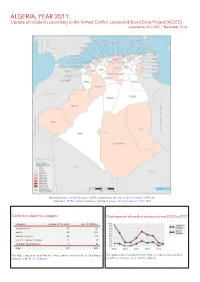

ALGERIA, YEAR 2011: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 7 November 2016 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2002 to 2011 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 91 32 battle 63 136 remote violence 20 33 violence against civilians 12 8 strategic developments 5 0 total 191 209 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). ALGERIA, YEAR 2011: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 7 NOVEMBER 2016 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Alger, 50 incidents killing 17 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Algiers, El Biar, El Harrach, Zeralda. In Annaba, 4 incidents killing 0 people were reported. The following location was affected: Annaba. In Aïn Defla, 2 incidents killing 0 people were reported. -

Pacification in Algeria, 1956-1958

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Pacification in Algeria 1956 –1958 David Galula New Foreword by Bruce Hoffman This research is supported by the Advanced Research Projects Agency under Contract No. SD-79. Any views or conclusions contained in this Memorandum should not be interpreted as representing the official opinion or policy of ARPA. -

Mérite Agricole En Algérie

Mise en ligne : 21 novembre 2016. Dernière modification : 3 mars 2021. www.entreprises-coloniales.fr TITULAIRES ALGÉRIENS DU MÉRITE AGRICOLE MÉRITE AGRICOLE (Le Temps, 19 décembre 1887) M. Javal, ingénieur à Bouënan, près Boufarik (Algérie). —————————— Ministère de l'agriculture Mérite agricole (Journal officiel de la république française, 8 mai 1895) Boulogne (Gaston-Laurent), commis principal au gouvernement général de l'Algérie : auteur de deux atlas de statistique agricole de l'Algérie. Délégué à l'exposition universelle de Lyon. Martin (Albert-César), sous-chef de bureau au gouvernement général de l'Algérie, secrétaire de différentes commissions agricoles. Robin (Jacques-Philippe-Eucher), inspecteur adjoint des forêts à Bône (Algérie) : constitution de collections forestières pour l'exposition universelle de Lyon ; 31 ans de services. ————————————— Ministère de l'agriculture Mérite agricole (Journal officiel de la république française, 6 août 1898) ALGÉRIE Grade d'officier. MM. Cabassot (Emmanuel-Mathias-François), agriculteur à Mascara (Algérie), vice- président du comice agricole de Mascara : nombreuses récompenses. Chevalier du 31 juillet 1894. Mairesebile (Paul-François-Désiré), gérant de l'oasis El-Amri, près Biskra (Algérie) : a grandement contribué à l'extension de la colonisation française dans la région saharienne des Zibans. Chevalier du 22 juillet 1891. Adda ben Lazereg ben Addi, président de douar-commune à Mendez (Algérie) : introduction de l'outillage agricole perfectionné. Chevalier du 26 juillet 1890. Hamlaoui Taïeb ben Hadj Hamana, agriculteur à Châteaudun-de-Rhumel (Algérie) : introduction, dans sa région, de l'outillage agricole perfectionné. Amélioration de l'élevage Plusieurs récompenses. Chevalier du 19 juillet 1893. ; Grade de chevalier. MM. Akermann (Pierre), propriétaire, adjoint spécial du centre de Blondel, commune mixte de Bibans (Constantine) : mise en valeur d'une importante exploitation agricole.