Too Many Notes: Computers, Complexity and Culture in Voyager

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

The Academy of Vocal Arts

April 7, 2005 Contact: Matthew Levy 215-893-0140 [email protected] Philadelphia Music Project 2005 Grant Recipients Academy of Vocal Arts, $60,000 to support concert versions of Le Portrait de Manon and La Navarraise, two important but rarely performed verismo operas by Jules Massanet. Vocalists will include James Valenti (tenor), Ailyn Perez (soprano), Jennifer G. Hsuing (mezzo-soprano), and Keith Miller (baritone). Performances will take place at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in January 2006. Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, $160,000 over two years to engage the American Composers Orchestra (ACO) in a residency that will bring ACO’s acclaimed Orchestra Underground programs to the Annenberg Center for a series of six new music concerts. Guest artists and organizations participating in the project include Todd Reynolds (violin), Ryuichi Sakamoto (laptop), Bill T. Jones, So Percussion, Pilobolus, and the Ridge Theater. The residency will include educational and outreach activities, as well as a program of works by Philadelphia- area composers. Choral Arts Society of Philadelphia, $30,000 to host Maestro Dale Warland, the former music director and founder of the Dale Warland Singers, as guest conductor for a program of works by Howard Hanson, Rudi Tas, Arvo Pärt, Benjamin Britten, James MacMillan, Frank Ferko, Alexandre Gretchaninoff, Vytautus Miškinis, and Henryk Górecki. A regional choral conducting workshop is also planned with Mr. Warland and CASP’s Artistic Director, Matthew Glandorf. Doylestown School of Music and the Arts, $12,140 in support of Stretched Strings, a series of four concerts exploring acoustic guitar practice within a variety of styles, including Travis Picking, Classical, Fingerstyle, and Blues. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

L'elysée Montmartre Ticket Reservation

A member of X-Japan in France ! Ra :IN in Paris the 5th of May 2005 Gfdgfd We have the pleasure to announce that the solo band of PATA (ex-X-Japan), Ra :IN, will perform live at the Elysee Montmartre in Paris (France) the 5th of May 2005. " Ra:IN " (pronounced "rah'een")----is an amazing unique, powerful new rock trio consisting of PATA (guitar-Tomoaki Ishizuka), one of the guitarists from the legendary Japanese rock band X Japan, michiaki (bass-Michiaki Suzuki), originally from another legendary Yokohama based rock band TENSAW, and Tetsu Mukaiyama (drums), who supported various bands and musicians such as Red Warriors and CoCCo. " Ra:IN " 's uniqueness comes from its musical eloquence. The three-piece band mainly delves into instrumental works, and the band's combination of colorful tones and sounds, along with the tight playing only possible with top-notch skilled players, provides an overwhelming power and energy that is what " ROCK " is all about. Just cool and heavy rhythms. But above all, don’t miss the first opportunity to see on stage in Europe a member of X-Japan, PATA (one of the last still performing). One of those that with their music, during years, warmed the heart of millions of fans in Japan and across the world. Ra :IN live in Paris website : http://parisvisualprod.free.fr Ra :IN website : http://www.rain-web.com Ticket Reservation Europe : Pre-Sales on Official Event Website : http://parisvisualprod.free.fr Japan : For Fan tour, please contact : [email protected] Worlwide (From 01st of March 2005) : TICKETNET -

Highly Anticipated Non-Profit Music Venue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Announces Opening, Curators, Programming Details and a New Name

For Immediate Release May 8, 2015 Press Contacts: Blake Zidell, John Wyszniewski and Ron Gaskill at Blake Zidell & Associates: 718.643.9052, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. HIGHLY ANTICIPATED NON-PROFIT MUSIC VENUE IN WILLIAMSBURG, BROOKLYN, ANNOUNCES OPENING, CURATORS, PROGRAMMING DETAILS AND A NEW NAME Beginning in October, National Sawdust (Formerly Original Music Workshop) Will Provide Composers and Musicians a State-of-the-Art Home for the Creation of New Work and Will Give Audiences and a Place to Discover Genre-Spanning Music at Accessible Ticket Prices Curators to Include Composers Anna Clyne, Bryce Dessner, David T. Little and Nico Muhly; Pianists Simone Dinnerstein and Anne Marie McDermott; Vocalists Helga Davis, Theo Bleckmann and Magos Herrera; and Violinists Miranda Cuckson and Tim Fain Groups and Artists in Residence to Include Brooklyn Rider, Glenn Kotche (Wilco), Alicia Hall Moran and Zimbabwe’s Netsayi Venue Partners and Collaborators Range from Carnegie Hall's Weill Music Institute and the New York Philharmonic’s CONTACT! to Stanford University and Williamsburg-Based El Puente Center for Arts and Culture National Sawdust +, Created by Elena Park, Will Include National Sawdust Talks as well as Performance Series that Offer Leading Directors and Writers, from Richard Eyre to Michael Mayer, a Platform to Share Their Musical Passions Opening Concerts in October to Feature Terry Riley, John Zorn, Roomful of Teeth, Nico Muhly, Bryce Dessner, Fence Bower Jon Rose, Throat Singer Tanya Tagaq and Others Brooklyn, NY (May 7, 2015) - The non-profit National Sawdust, formerly known as Original Music Workshop, is pleased to announce that its highly anticipated, state-of-the-art, Williamsburg, Brooklyn venue will open this fall. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

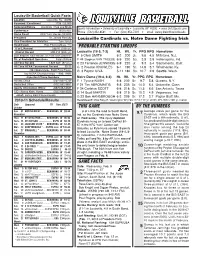

Probable Starting Lineups This Game by the Numbers

Louisville Basketball Quick Facts Location Louisville, Ky. 40292 Founded / Enrollment 1798 / 22,000 Nickname/Colors Cardinals / Red and Black Sports Information University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 www.UofLSports.com Conference BIG EAST Phone: (502) 852-6581 Fax: (502) 852-7401 email: [email protected] Home Court KFC Yum! Center (22,000) President Dr. James Ramsey Louisville Cardinals vs. Notre Dame Fighting Irish Vice President for Athletics Tom Jurich Head Coach Rick Pitino (UMass '74) U of L Record 238-91 (10th yr.) PROBABLE STARTING LINEUPS Overall Record 590-215 (25th yr.) Louisville (18-5, 7-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Asst. Coaches Steve Masiello,Tim Fuller, Mark Lieberman F 5 Chris SMITH 6-2 200 Jr. 9.8 4.5 Millstone, N.J. Dir. of Basketball Operations Ralph Willard F 44 Stephan VAN TREESE 6-9 220 So. 3.5 3.9 Indianapolis, Ind. All-Time Record 1,625-849 (97 yrs.) C 23 Terrence JENNINGS 6-9 220 Jr. 9.3 5.4 Sacramento, Calif. All-Time NCAA Tournament Record 60-38 G 2 Preston KNOWLES 6-1 190 Sr. 14.9 3.7 Winchester, Ky. (36 Appearances, Eight Final Fours, G 3 Peyton SIVA 5-11 180 So. 10.7 2.9 Seattle, Wash. Two NCAA Championships - 1980, 1986) Important Phone Numbers Notre Dame (19-4, 8-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Athletic Office (502) 852-5732 F 1 Tyrone NASH 6-8 232 Sr. 9.7 5.8 Queens, N.Y. Basketball Office (502) 852-6651 F 21 Tim ABROMAITIS 6-8 235 Sr. -

Richard Teitelbaum

RICHARD TEITELBAUM . f lectro-Acoustic Chamber Music February 27-28, 1979 8:30pm $3.50 / $2.00 members / TDF Music The Kitchen Center 484 Broome Street On February 27- 28, The Kitchen Center will present works by Richard Teitel baum. Performers of the compositions and improvisations on the program include George Lewis, trombone and electronics; Reih i Sano, shakuhachi; and Richard Teitel baum, Pol yMoog, MicroMoog and modular Moog synthesizers. The program of electro-acoustic chamber music opens with "Blends," a piece for shakuhachi and synthesizers featuring the playing of Reihi Sano. The piece was composed and first per- formed in 1977, while Teitelbaum was studying in Japan on a Fullbright scholarship. Reihi Sano, who is currently an artist-in-residence at Wesleyan University, has a virtuoso command of the shakuhachi, the endblown bamboo flute. This performance of "Blends" is an American premiere. Similarly, a new work with George Lewis, incorporates Lewis's prodigious com- mand of the trombone and live electronics in a semi-improvisational piece. George Lewis has been involved with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians since 1971, and has played with musicians as diverse as Anth0n.y Braxton, Phil Niblock and Count Basie, in addition to studying philosophy at Yale University. Teitelbaum and Lewis have played at Axis In SoHo, Studio RivBea and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. An extensive synthesizer solo by Teitelbaum, entitled "Shrine" (1976-78) rounds out the concert program. Richard Teitelbaum is one of the prime movers of live electronic music. Classically trained, and with a Master's degree in Music from Yale, he studied in Italy with Luigi Nono. -

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager����� Lewis, George E

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager Lewis, George E. Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 10, 2000, pp. 33-39 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lmj/summary/v010/10.1lewis.html Access Provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz at 09/27/11 9:42PM GMT W A Y S WAYS & MEANS & M E A Too Many Notes: Computers, N S Complexity and Culture in Voyager ABSTRACT The author discusses his computer music composition, Voyager, which employs a com- George E. Lewis puter-driven, interactive “virtual improvising orchestra” that ana- lyzes an improvisor’s performance in real time, generating both com- plex responses to the musician’s playing and independent behavior arising from the program’s own in- oyager [1,2] is a nonhierarchical, interactive mu- pears to stand practically alone in ternal processes. The author con- V the trenchancy and thoroughness tends that notions about the na- sical environment that privileges improvisation. In Voyager, improvisors engage in dialogue with a computer-driven, inter- of its analysis of these issues with ture and function of music are active “virtual improvising orchestra.” A computer program respect to computer music. This embedded in the structure of soft- ware-based music systems and analyzes aspects of a human improvisor’s performance in real viewpoint contrasts markedly that interactions with these sys- time, using that analysis to guide an automatic composition with Catherine M. Cameron’s [7] tems tend to reveal characteris- (or, if you will, improvisation) program that generates both rather celebratory ethnography- tics of the community of thought complex responses to the musician’s playing and indepen- at-a-distance of what she terms and culture that produced them. -

Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hf4q6w5 Journal Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, 1(3) Author Dessen, MJ Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 1, No 3 (2006) Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Michael Dessen, Hampshire College Introduction Throughout the twentieth century, African American improvisers not only created innovative musical practices, but also—often despite staggering odds—helped shape the ideas and the economic infrastructures which surrounded their own artistic productions. Recent studies such as Eric Porter’s What is this Thing Called Jazz? have begun to document these musicians’ struggles to articulate their aesthetic philosophies, to support and educate their communities, to create new audiences, and to establish economic and cultural capital. Through studying these histories, we see new dimensions of these artists’ creativity and resourcefulness, and we also gain a richer understanding of the music. Both their larger goals and the forces working against them—most notably the powerful legacies of systemic racism—all come into sharper focus. As Porter’s book makes clear, African American musicians were active on these multiple fronts throughout the entire century. Yet during the 1960s, bolstered by the Civil Rights