Inventory of Scottish Battlefields NGR Centred: NJ 562

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Colonial Scottish Jacobite Family

A COLONIAL SCOTTISH JACOBITE FAMILY THE ESTABLISHMENT IN VIRGINIA OF A BRANCH OF THE HUM-ES of WEDDERBURN Illustrated by Letters and Other Contemporary Documents By EDGAR ERSKINE HUME M. .A... lL D .• LL. D .• Dr. P. H. Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Member of the Virginia and Kentucky Historical Societies OLD DoKINION PREss RICHMOND, VIRGINIA 1931 COPYRIGHT 1931 BY EDGAR ERSKINE HUME .. :·, , . - ~-. ~ ,: ·\~ ·--~- .... ,.~ 11,i . - .. ~ . ARMS OF HUME OF WEDDERBURN (Painted by Mr. Graham Johnston, Heraldic Artist to the Lyon Office). The arms are thus recorded in the Public ReJ?:ister of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland (Court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms) : Quarterly, first and fourth, Vert a lion rampant Argent, armed and langued Gules, for Hume; second Argent, three papingoes Vert, beaked and membered Gules, for Pepdie of Dunglass; third Argent, a cross enirrailed Azure for Sinclair of H erdmanston and Polwarth. Crest: A uni corn's head and neck couped Argent, collared with an open crown, horned and maned Or. Mottoes: Above the crest: Remember; below the shield: True to the End. Supporters: Two falcons proper. DEDICATED To MY PARENTS E. E. H., 1844-1911 AND M. S. H., 1858-1915 "My fathers that name have revered on a throne; My fathers have fallen to right it. Those fathers would scorn their degenerate son, That name should he scoffingly slight it . " -BORNS. CONTENTS PAGE Preface . 7 Arrival of Jacobite Prisoners in Virginia, 1716.......... 9 The Jacobite Rising of 1715. 10 Fate of the Captured Jacobites. 16 Trial and Conviction of Sir George Hume of Wedder- burn, Baronet . -

I General Area of South Quee

Organisation Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line3 City / town County DUNDAS PARKS GOLFGENERAL CLUB- AREA IN CLUBHOUSE OF AT MAIN RECEPTION SOUTH QUEENSFERRYWest Lothian ON PAVILLION WALL,KING 100M EDWARD FROM PARK 3G PITCH LOCKERBIE Dumfriesshire ROBERTSON CONSTRUCTION-NINEWELLS DRIVE NINEWELLS HOSPITAL*** DUNDEE Angus CCL HOUSE- ON WALLBURNSIDE BETWEEN PLACE AG PETERS & MACKAY BROS GARAGE TROON Ayrshire ON BUS SHELTERBATTERY BESIDE THE ROAD ALBERT HOTEL NORTH QUEENSFERRYFife INVERKEITHIN ADJACENT TO #5959 PEEL PEEL ROAD ROAD . NORTH OF ENT TO TRAIN STATION THORNTONHALL GLASGOW AT MAIN RECEPTION1-3 STATION ROAD STRATHAVEN Lanarkshire INSIDE RED TELEPHONEPERTH ROADBOX GILMERTON CRIEFFPerthshire LADYBANK YOUTHBEECHES CLUB- ON OUTSIDE WALL LADYBANK CUPARFife ATR EQUIPMENTUNNAMED SOLUTIONS ROAD (TAMALA)- IN WORKSHOP OFFICE WHITECAIRNS ABERDEENAberdeenshire OUTSIDE DREGHORNDREGHORN LOAN HALL LOAN Edinburgh METAFLAKE LTD UNITSTATION 2- ON ROAD WALL AT ENTRANCE GATE ANSTRUTHER Fife Premier Store 2, New Road Kennoway Leven Fife REDGATES HOLIDAYKIRKOSWALD PARK- TO LHSROAD OF RECEPTION DOOR MAIDENS GIRVANAyrshire COUNCIL OFFICES-4 NEWTOWN ON EXT WALL STREET BETWEEN TWO ENTRANCE DOORS DUNS Berwickshire AT MAIN RECEPTIONQUEENS OF AYRSHIRE DRIVE ATHLETICS ARENA KILMARNOCK Ayrshire FIFE CONSTABULARY68 PIPELAND ST ANDREWS ROAD POLICE STATION- AT RECEPTION St Andrews Fife W J & W LANG LTD-1 SEEDHILL IN 1ST AID ROOM Paisley Renfrewshire MONTRAVE HALL-58 TO LEVEN RHS OFROAD BUILDING LUNDIN LINKS LEVENFife MIGDALE SMOLTDORNOCH LTD- ON WALL ROAD AT -

Heritage Festival 2017

Heritage Festival 2017 Where People, Place & Myth Meet PROGRAMME OF EVENTS PICTURING THE PAST: LIGHTING THE BORDERS PHOTOGRAPHY COMPETITION Lantern making workshops Entries by midnight, Friday 11 August 2017 11 August, 11.00–13.00 & 14.00–17.00 Live Borders Libraries & Archives, Newcastleton Village Hall, Newcastleton St Mary’s Mill, Selkirk TD7 5EW TD9 0QD. Parade: Sat 2 September meeting Entry Free at 20.00, Hermitage Castle, Newcastleton Celebrate Scotland’s Year of History, 12 August, 11.00–13.00 & 14.00–17.00 Heritage & Archaeology by capturing Duns Parish Hall, Church Square, Duns TD11 your Borders heritage through photography. 3DD. Parade: Friday 1 September meeting Do you have a favourite building, monument at 19.00 Market Square, Duns or archaeological feature in the Scottish Come along and make your own willow Borders? Why not get out and about with and tissue paper lantern for our spectacular your camera this summer? Entering is easy! public parades in Duns and Newcastleton! 1. You must be within one of these three These workshops are free with a small categories when the competition closes: donation (£2) towards materials appreciated. 11 years and under, 12–17 years, 18–25 years. Wear old clothes and bring your family 2. Download an entry form, which includes along. Drop in sessions – please allow at full conditions of entry: www.liveborders. least 1 hour to make your lantern. For more org.uk/librariesandarchives information on lantern making workshops please contact Sara. 3. A digital copy of the image along with the completed entry form must be submitted via &[email protected] email to [email protected]. -

Guide to R Ural Scotland the BORDERS

Looking for somewhere to stay, eat, drink or shop? www.findsomewhere.co.uk 1 Guide to Rural Scotland THE BORDERS A historic building B museum and heritage C historic site D scenic attraction E flora and fauna F stories and anecdotes G famous people H art and craft I entertainment and sport J walks Looking for somewhere to stay, eat, drink or shop? www.findsomewhere.co.uk 2 y Guide to Rural Scotland LOCATOR MAP LOCATOR EDINBURGH Haddington Cockburnspath e Dalkeith Gifford St. Abbs Grantshouse EAST LOTHIAN Livingston Humbie W. LOTHIAN Penicuik MIDLOTHIAN Ayton Eyemouth Temple Longformacus Preston West Linton Duns Chirnside Leadburn Carfraemill Lauder Berwick Eddleston Greenlaw Stow Peebles Coldstream THE BORDERS Biggar Eccles Galashiels Lowick Melrose Broughton Kelso Thornington Traquair n Yarrow Selkirk Roxburgh Kirknewton Tweedsmuir Ancrum Ettrickbridge Morebattle BORDERS (Scottish) Jedburgh Ettrick Hawick Denholm Glanton Bonchester Bridge Carter Moffat Bar Davington Teviothead Ramshope Rothbury Eskdalemuir Saughtree Kielder Otterburn Ewesley Boreland Kirkstile Castleton Corrie Stannersburn Newcastleton Risdale M Lochmaben Langholm Lockerbie NORTHUMBERLAND Towns and Villages Abbey St Bathans pg 7 Eyemouth pg 9 Mellerstain pg 18 Ancrum pg 33 Fogo pg 15 Melrose pg 18 Ayton pg 9 Foulden pg 10 Minto pg 31 Broughton pg 41 Galashiels pg 16 Morebattle pg 34 Chirnside pg 9 Gordon pg 18 Neidpath Castle pg 38 Clovenfords pg 17 Greenlaw pg 15 Newcastleton pg 35 Cockburnspath pg 7 Hawick pg 30 Paxton pg 10 Coldingham pg 8 Hutton pg 9 Peebles pg 36 -

Print This Article

Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History Volume 15 May 2015 WHEN WAS THE SCOTTISH NEW YEAR? SOME UNRESOLVED PROBLEMS WITH THE ‘MOS GALLICANUS’, OR FRENCH STYLE, IN THE MID-SIXTEENTH CENTURY1 Elizabeth Bonner st N 1600 the 1 of January was ordained as the first day of the New I Year in Scotland. By this ordinance the Kingdom of Scotland joined the great majority of Western European kingdoms, states and territories who had, at various times during the sixteenth century, rationalized the reckoning of Time by declaring the 1st January as New Year’s Day.2 This article will examine, very briefly, the long history of the reckoning of Time as calculated in ancient western civilizations. During the sixteenth century, however, these calcula- tions were rationalised in the culmination of the political and religious upheavals of the Renaissance and Reformations in Western Europe. In Scotland, for a brief period under the influence of the French government from 1554 to 1560 during the Regency of Marie de Guise-Lorraine,3 and from 1561 to 1567 during the personal reign of her daughter Mary Queen of Scots, the mos Gallicanus, which recognised Easter Sunday as the first day of the New Year, was used in a great number of French official state documents, dispatches and correspondence. We will also note the failure by some past editors to recognise this change, which leaves the date of some important 1 I am most grateful to the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh for a visiting scholarship in 1995, where this work was first presented. -

The SCOTTISH BORDERS

EXPLORE 2020-2021 The SCOTTISH BORDERS visitscotland.com Contents 2 The Scottish Borders at a glance 4 A creative hub 6 A dramatic past 8 Get active outdoors 10 Discover Scotland’s leading cycling destination 12 Local flavours 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit 41 Leisure activities 46 Shopping Welcome to… 49 Food & drink 52 Accommodation THE SCOTTISH 56 Regional map BORDERS Step out into the rolling hills, smell the spring flowers in the forest, listen to the chattering river and enjoy the smiles of the people you meet. Welcome to the Scottish Borders, a very special part of the country that will captivate you instantly. Here you’ll find wild, wide-open landscapes, a buzzing cultural scene, a natural larder to die for and outdoor activities for the most adventurous of thrill-seekers. The Scottish Borders is also a place where the past lives Cover: Kelso Abbey around us – in ancient abbeys, historic Above image: Mellerstain House, walking routes and the stories told by the near Kelso people you’ll meet. Discover the wealth of incredible experiences in the forests and Credits: © VisitScotland. along the coastline of the Scottish Borders – Kenny Lam, Ian Rutherford, get active, discover great attractions and have Paul Tomkins, Johnstons of Elgin/ an adventure! Angus Bremner, David N Anderson, Cutmedia, David Cheskin 20SBE Hawico Factory Visitor Centre Kelso Outlet Store Arthur Street 20 Bridge Street Produced and published by APS Group Scotland (APS) in conjunction with VisitScotland (VS) and Highland News & Media (HNM). -

The Bloody Buffer State

The Bloody Buffer State Rough Wooing - Background Because the ancient Kingdom of Bernicia had stretched from the Forth to the Tyne, kings of both England and Scotland had claimed Northumberland as theirs. The Treaty of York in 1237 effectively settled the borderline between England and Scotland with the formation of East, Middle and West Marches. For centuries the northern English and the southern Scots pillaged among their neighbours and developed their own system of thieving and armed thuggery that has been called reiving. The whole system fi nally fell apart when James VI inherited the throne of England on the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603 and the anarchy among the families on both sides of the Borders could be quashed. The 16th century was the bloodiest in the history of the Borders and the bloodiest period of that bloody century was 1544-47 in what became known as England’s Rough Wooing. There were three campaigns, those in 1544 and 1547 were largely against Edinburgh and the Lothians. In 1513, England was fi ghting France in Flanders. France, desperate for a diversion, appealed to James IV to attack England from the north and James responded by fi elding the largest army Scotland had every seen – between 60,000 and 100,000 men. By the time the two armies met at Flodden in Northumberland, the English had already routed the French in Flanders and now proceeded, under the Earl of Surrey, to annihilate the Scots. James IV, his bastard son Alexander, 13 earls and thousands of lesser ranks were killed. -

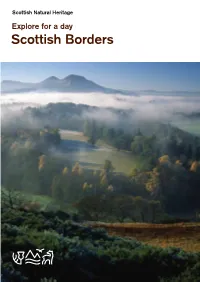

Explore for a Day Scottish Borders Scottish Borders

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a day Scottish Borders Scottish Borders Welcome to the natural beauty and colourful history of the Scottish Borders. Nestled within the Moorfoot, Lammermuir and Cheviot Hills, the Border country follows the path of the mighty River Tweed and extends to a spectacular stretch of coastline in the east. The river flows through the region from west to east, and forms part of the border with England. Symbol Key From rolling hills and moorland to lush woods and valleys, the area has some outstanding scenery and supports a variety of wildlife. Look out for red squirrels, otters, and all kinds of birds, including the mighty osprey, Parking Information Centre as you stretch your legs on one of the many paths and trails. Enjoy the seasonal splendour of spring flowers, autumn leaves and summer’s purple heather blooms. Paths Disabled Access Soak up the area’s enthralling history. Visit historic houses, ruined abbeys and castles as you travel through magnificent scenery. The magical Toilets Wildlife watching landscape is steeped in myth and folklore, and has inspired many artists and writers, such as Sir Walter Scott and James Hogg. Refreshments Picnic Area This leaflet contains five suggested itineraries for you to follow or use to create your own special natural and cultural experience of the Scottish Borders. Admission free unless otherwise stated. For those who’ve never visited the area before, you’re in for a treat; for the people who live here, you may discover new, amazing places. Once explored, the Borders are hard to forget. People find themselves returning again and again. -

Item No. 4 SCOTTISH BORDERS COUNCIL PLANNING and BUILDING STANDARDS COMMITTEE

Item No. 4 SCOTTISH BORDERS COUNCIL PLANNING AND BUILDING STANDARDS COMMITTEE MINUTE of MEETING of the PLANNING AND BUILDING STANDARDS COMMITTEE held in the Council Headquarters, Newtown St. Boswells on 1 July 2013 at 10 a.m. ------------------ Present: - Councillors R. Smith (Chairman), M. Ballantyne, S. Bell, J. Brown, J. Campbell, A. Cranston, J. Fullarton, I. Gillespie, D. Moffat, S. Mountford, B. White. Apologies:- Councillors N. Buckingham, V. Davidson. In Attendance:- Head of Planning & Regulatory Services, Development Manager (Applications), Senior Roads Planning Officers, Managing Solicitor – Commercial Services, Democratic Services Team Leader. MINUTE 1. There had been circulated copies of the Minute of the Meeting of 3 June 2013. DECISION APPROVED for signature by the Chairman. PLANNING PERFORMANCE UPDATE 2. The Head of Planning and Regulatory Services provided Members with information on the historical measures, trends and performance which were measured in terms of the speed of determining applications, the percentage of population covered by an up-to-date Development Plan and the appeal success rates. These measures had been replaced by the new Planning Performance Framework (PPF). This PPF included a number of new measures covering matters such as communications, engagement and customer service, efficient and effective decision making and a culture of continuous improvement. Feedback on the 1st PPF had now been received from Government and this had mainly been very positive with areas for improvement including a need to also focus on average timescales and tackle some of the longer-running applications, including those subject to legal agreements, which were having a detrimental effect on the department’s statistics. -

Kelso, Past and Present

A elso,. Past and JgRESENT; Being the First Urunlees Prize Essay, 1872: TO WHICH IS ADDED Notices of the Industries of the Town, and an Historical Sketch of Roxburgh Castle. By W. FRED. VERNON. j KELSO: H. RUTHERFURD, 2G , SQUARE. 1873. $d|o, |)a$t and :jrc|cnf; Being the First Brunlees Prize Essay, 1872: TO WHICH IS ADDED fiothzs oi the IvUmsttks #f the ^otott, AND AN Historical Sketch of Roxburgh Castle. By W. FRED. VERNON. KELSO: J. & J. H. RUTHERFURD, 20, SQUARE. 1873. ; " Bosomed in woods where mighty rivers run, Kelso's fair vale expands before the sun, Its rising downs in vernal beauty swell, And, fringed with hazel, winds each flowery dell Green spangled plains to dimpling lawns succeed, And Tempe rises on the banks of Tweed. Blue o'er the river Kelso's shadow lies, And copse-clad isles amid the waters rise ; Where Tweed her silent way majestic holds, Float the thin gales in more transparent folds." Dr Leyden, "Scenes of Infancy' Works consulted in this Essay. Ridpath's " Border History of England and Scotland. 17 1 ' Jeffrey's " History and Antiquities of Roxburghshire. Haig's " History of Kelso." Mason's " Kelso Records." Tytler's " History of Scotland." Scott's " Border Minstrelsy." Rutherfurd's " Southern Counties' Register and Direc- tory." The Kelso Mail, Kelso Chronicle, &c, &c. |^t$o, :)a|t m& :]vt§t\xt PART L—KELSO PAST. INTRODUCTION—PRE-HISTORIC KELSO. jjLTHOUGH the prime origin of our beautiful and thriving little town is obscured by the gathered mists of ages, it requires but little stretch of the imagina- tion to peer into the past and to see the north bank of the Tweed, near its confluence with the Teviot, peopled with a colony of early settlers. -

Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History Volume 6 June 1998

Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History Volume 6 June 1998 The French Reactions to the Rough Wooings of Mary Queen of Scots Elizabeth Bonner The French Reactions to the Rough Wooings of Mary Queen of Scots Elizabeth Bonner The Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History Volume 6 J one 1998 JOURNAL OF THE SYDNEY SOCIETY FOR SCOTTISH HISTORY Volume No.6, June 1998. Patron: Professor Michael Lynch, Sir William Fraser Professor of Scottish History and Palaeography, University of Edinburgh. COMMITTEE OF THE SOCIETY ELECTED FOR 1998 President: Malcolm D. Broun QC, BA(Hons), LLB (University of Sydney), on whom the Celtic Council of Australia has conferred the honour of 'Cyfaill y Celtiaid' (Friend of the Celts). Vice-Presidents: Elizabeth Ann Bonner, BA(Hons) Ph.D. University of Sydney, Paper Convenor and Co-editor. James Thorburn., retired Bookseller and Antiquarian Hon. Secretary: Valerie Smith, Secretary of The Scottish Australian Heritage Council. Hon. Treasurer: lain MacLulich, Major, (retired) a Scottish Armiger. Editor: Gwynne F.T. Jones, D.Phil. Oxford, MA New Zealand. Committee Members: Ethel McK.irdy-Walker, BA University of NSW, MA University of Sydney. Cecile Ramsay-Sharp. The Sydney Society for Scottish History Edmund Barton Chambers Level 44, M.L.C. Building Sydney N.S.W. 2000 AUSTRALIA Tel. (02) 9220 6144 Fax. (02) 9232 3949 Printed by University of Sydney Printing Service University of Sydney, N.S.W. 2006, AUSTRALIA. ISSN: 1320-4246 CONTENTS page Introduction . .. MALCOLM BROUN Preface 5 The French Reactions to the Rough Wooings of Mary Queen of Scots ... 9 French Reaction to the 1st 'Rough Wooing': Fran9ois I and Hemy VIII .. -

Local Society and the Defence of the English Frontier in Fifteenth-Century Scotland: the War Measures of 1482*

Local Society and the Defence of the English Frontier in Fifteenth-Century Scotland: The War Measures of 1482* Jackson W. Armstrong Despite a growing body of research on political society in late medieval Scotland, and on Anglo-Scottish war, truce, and frontier administration, exactly how local bor- der society responded to the threat of warfare with England is not well understood. Source materials lend themselves to analysis of the military careers of great magnate dynasties,1 but not to an investigation of the roles performed by the lesser nobility of the borderlands whose fortified residences offered the first line of national defence, and who constituted that social group which conveyed royal and magnate power in the localities.2 The late medieval Anglo-Scottish frontier is the subject of two outstand- ing recent monographs. In 1998, Cynthia Neville examined the development of inter- national border or ‘march’ law, illuminating the judicial role of those royal officials known as wardens of the march and truce conservators and the influence on law and on administration of Anglo-Scottish diplomacy from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century. Whereas Neville expanded on the legal dimensions of the region’s history, * This paper and the accompanying map have been greatly strengthened by comment and discussion at different stages offered by Christine Carpenter, Aly Macdonald, Andy King, Jonathan Gledhill, Matt Aitkenhead, Rosalyn Trigger, Dan Maccannell, Florilegium’s anonymous readers, and the participants in the military history conference convened by David Simpkin and Craig Lambert at the Univer- sity of Hull in April 2007. 1 The most important study of this type, concerned with far more than military matters, and related to this region, is Brown, The Black Douglases; on organization for war, see esp.