Preserving a Biological Treasure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

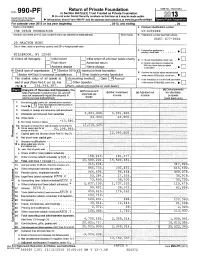

Form 990-PF Or Section 4947{A){1)Trust Treated As Privatefoundation JI,- Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947{a){1)Trust Treated as PrivateFoundation JI,- Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. ~@13 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service .... Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar vear 2013 or tax vear beclnnlnq , 2013, and endina , 20 Name of foundation A EmployerIdentification number THE DYSON FOUNDATION 13-6084888 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see Instructions) (845) 677-0644 25 HALCYON ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application Is ...._ pending, check here , , • • • • ,.... O MILLBROOK,NY 12545 G Checkall thatapply: _ Initia! return Initial returnof a formerpublic charity - O 1. Foreign organizations, check hare - Finalreturn - Amendedreturn 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chanae Name chanae computation • • • • • • • , H Checktype of organization:I X I Section501 ( ccr93 exemptprivate foundation L.:..:..J E If private foundation status was terminated o n Section 4947( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable orivate foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here • .... I J F Fair marketvalue of all assets at Accountingmethod:LJ Cash ~ Accrual If the foundation is in a eo-month termination D end of year(from Part fl, co/.(c), line O Other(specify)---------------------- under section 507(b)(1)(B), check hare • ... -

Pro Te Cting the Sha W Angunks

SHAWANGUNKS PROTECTING THE PROTECTING For people. wildlife. Forever. RIVER-TO-RIDGE TRAIL White Oak Bend Path Wallkill River The River-to-Ridge Trail was created in partnership by the Open Space Institute (OSI) and Mohonk Preserve, with the R2R support of the Butler Conservation RIVER-TO-RIDGE Fund. The trail traverses land conserved TRAIL by OSI and is intended for public use and enjoyment. This six-mile loop trail connects the Wallkill Valley Rail Trail/ Empire State Trail in the Village of New Paltz to the carriage roads and footpaths of the Shawangunk Ridge. Because the River-to-Ridge Trail runs along active farmland and is adjacent to private property, visitors are required to stay on the trail and respect the agricultural operations and neighboring properties. RULES OF THE TRAIL The River-to-Ridge Trail is open dawn to dusk, and admission is free to trail users. For your safety and enjoyment, we ask that trail users and guests help maintain the operation of this trail by following and helping others follow these simple rules. No Motorized Vehicles Clean Up After Pets No Camping Stay on Trail No Smoking No Hunting or Trapping No Dumping or Littering No Alcohol or Drugs No Firearms Leash Your Pets No Campfire No Drones Helmets Required for Cyclists ABOUT THE OPEN SPACE INSTITUTE The Open Space Institute (OSI) protects Committed to protecting the 50-mile scenic, natural and historic landscapes Shawangunk Ridge and improving public to provide public enjoyment, conserve access to protected lands, OSI is also habitat and working lands, and sustain supporting the creation of a local rail trail communities from Canada to Florida. -

GUIDE to the SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS SCENIC BYWAY and REGION Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Access Map

GUIDE TO THE SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS SCENIC BYWAY AND REGION Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Access Map Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Other State Scenic Byways G-2 How To Get Here Located in the southeast corner of the State, in southern Ulster and northern Orange counties, the Shawangunk Mountains Scenic Byway is within an easy 1-2 hour drive for people from the metro New York area or Albany, and well within a day’s drive for folks from Philadelphia, Boston or New Jersey. Access is provided via Interstate 84, 87 and 17 (future I86) with Thruway exits 16-18 all good points to enter. At I-87 Exit 16, Harriman, take Rt 17 (I 86) to Rt 302 and go north on the Byway. At Exit 17, Newburgh, you can either go Rt 208 north through Walden into Wallkill, or Rt 300 north directly to Rt 208 in Wallkill, and you’re on the Byway. At Exit 18, New Paltz, the Byway goes west on Rt. 299. At Exit 19, Kingston, go west on Rt 28, south on Rt 209, southeast on Rt 213 to (a) right on Lucas Turnpike, Rt 1, if going west or (b) continue east through High Falls. If you’re coming from the Catskills, you can take Rt 28 to Rt 209, then south on Rt 209 as above, or the Thruway to Exit 18. From Interstate 84, you can exit at 6 and take 17K to Rt 208 and north to Wallkill, or at Exit 5 and then up Rt 208. Or follow 17K across to Rt 302. -

Featured Hiking and Biking Trails

Lake Awosting, Minnewaska State Park State Minnewaska Awosting, Lake View from Balsam Mountain Balsam from View Bluestone Wild Forest Forest Wild Wild Bluestone Bluestone Hudson Hudson the the Over Over Walkway Walkway Trails Biking Biking Hiking and Mohonk Mountain House House Mountain Mohonk Featured Reservoir Ashokan Hudson River Towns & Cities 6 Falling Waters Preserve (Town of Saugerties) 12 Mohonk Preserve Approximately two miles of varied trails exist on this 149-acre preserve. The trails (Towns of Rochester, Rosendale, Marbletown) 1 Walkway Over the Hudson & Hudson Valley are an excellent place to explore the rugged beauty of the Hudson River, while Located just north of Minnewaska Park, Mohonk Preserve is New York State’s Rail Trail hiking atop rock ledges that slant precipitously into the water. The 0.65-mile largest visitor- and member-supported nature preserve with 165,000 annual (Hamlet of Highland, Town of Lloyd) white-blazed Riverside Trail hugs the river and offers great views. The 0.9-mile visitors and 8,000 protected acres of cliffs, forests, fields, ponds and streams. The Walkway Over the Hudson (Walkway), the longest-elevated pedestrian walkway red-blazed Upland Trail affords views of the Catskills and a picturesque waterfall. Named one of the five best city escapes nationwide by Outside magazine, Mohonk in the world, spans the Hudson River between Poughkeepsie and Highland and links www.scenichudson.org/parks/fallingwaters Preserve maintains over 70 miles of carriage roads and 40 miles of trails for together an 18-mile rail trail network on both sides of the Hudson. Connected to the Saugerties Lighthouse Trail (Village of Saugerties) hiking, cycling, trail running, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and horseback 7 riding along the Shawangunk Mountains. -

Catskill Mountain Rail Trail

“We have a unique opportunity to create a world-class tourism destination, directly impact public health, and improve the overall quality of life in our region.” -Ulster County Executive Michael P. Hein 1 Project Vision: Walkway over the Hudson Develop a public recreational trail from Kingston to and along the Ashokan Reservoir that will link the Hudson River and Walkway over the Hudson to the Catskill Park and create a world-class tourism destination. Project Goals: Ashokan Reservoir Connect Kingston neighborhoods to Catskill Park & Ashokan Reservoir Expand tourism business in Ulster County and Hudson Valley region Increase outdoor recreation opportunities and promote healthy lifestyles Provide “car-free” transportation options Create links to the Hurley/ O&W Rail Trail & Wallkill Valley Rail Trail 2 Background and Brief History: Railroad chartered and construction started (1866) Line extended from Kingston to Oneonta (1900) U&D Railroad carries 676,000 to Catskill resorts (1913) Last train leaves Kingston (1976) Ulster County purchases 38.6 miles of U&D corridor-- City of Kingston to Delaware County border (1979) County signs 25-year lease with Catskill Mountain Railroad Company (1991) for tourism railroad operations Limited local freight service ends (1996) Planning Study considers feasibility of rail trail (2006) County Executive Michael Hein proposes development of Catskill Mountain Rail Trail (2012) from City of Kingston to the Ashokan Reservoir and west into the Catskills Governor Andrew Cuomo includes $2 million for rail trail in 2013-2014 New York State Budget (2013) 3 Growing Importance of Regional Rail Trails: • Walkway over the Hudson (opened 2009) attracted more than 780,000 visitors in first year and now adds more than $24 million annual sales. -

FY 2017 Annual Report

COVER PENDING If not for the collective voices of trail supporters and advocates over the past half-century, rail-trails around the country would never have come into existence. Since 1986, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) has served as the national voice for the rail-trail movement, elevating the hard work of these supporters and advocates to Congress, public leaders and influencers across America. We have set the precedent that rail-trails are need-to-have community assets and have established the policies that ensure these trails are built. With more than 2,000 rail-trails and more than 32,000 miles of multiuse trails on the ground nationwide, RTC's focus is on linking these corridors—creating trail networks that connect people and places and transforming communities all across the country. Explore the difference we've made. Table of Contents Explore the Difference We’ve Made ....................... 1 Research Into Practice ............................................... 18 Building a Nation of Trails ........................................ 2 Celebrating Our Champions .................................... 20 How We Make Change ............................................. 3 Expanding the Movement ........................................ 22 Transforming America’s Communities .................... 4 Financials .................................................................... 25 Advocating for America’s Trails ............................... 6 Board of Directors ..................................................... 26 Connecting America’s -

Zenas King and the Bridges of New York City

Volume 1, Number 2 November 2014 From the Director’s Desk In This Issue: From the Director’s Desk Dear Friends of Historic Bridges, Zenas King and the Bridges of New Welcome to the second issue of the Historic Bridge York City (Part II) Bulletin, the official newsletter of the Historic Bridge Hays Street Bridge Foundation. Case Study: East Delhi Road Bridge As many of you know, the Historic Bridge Foundation advocates nationally for the preservation Sewall’s Bridge of historic bridges. Since its establishment, the Historic Bridge Collector’s Historic Bridge Foundation has become an important Ornaments clearinghouse for the preservation of endangered bridges. We support local efforts to preserve Set in Stone significant bridges by every means possible and we Upcoming Conferences proactively consult with public officials to devise reasonable alternatives to the demolition of historic bridges throughout the United States. We need your help in this endeavor. Along with Zenas King and the Bridges our desire to share information with you about historic bridges in the U.S. through our newsletter, of New York City (Part II) we need support of our mission with your donations to the Historic Bridge Foundation. Your generous King Bridge Company Projects in contributions will help us to publish the Historic New York City Bridge Bulletin, to continue to maintain our website By Allan King Sloan at www.historicbridgefoundation.com, and, most importantly, to continue our mission to actively promote the preservation of bridges. Without your When Zenas King passed away in the fall of 1892, help, the loss of these cultural and engineering his grand plan to build two bridges across the East landmarks threatens to change the face of our nation. -

New Paltz Engineering, Childcare, and Trails 2019

VILLAGE OF NEW PALTZ ∎ ENGINEERING, CHILDCARE, AND TRAILS ∎ 2019 DRI Application BASIC INFORMATION Regional Economic Development Council: Mid-Hudson REDC Municipality Name: Village of New Paltz & Town of New Paltz Downtown Name: Downtown New Paltz County Name: Ulster County Applicant Contact: Tim Rogers, Mayor of the Village of New Paltz Applicant Email Addresses: [email protected]; [email protected] Q: HOW TO SUPPORT NEW PALTZ? A: ENGINEERING, CHILDCARE, and TRAILS VISION FOR DOWNTOWN We will re-energize and reinvigorate our position as one of the State’s most dynamic villages by combining strategic investment in New Paltz’s downtown core, SUNY New Paltz’s innovative programming, and the new Empire State Trail intersecting our village. The Village of New Paltz is poised to become the Mid-Hudson REDC’s first-ever village to receive the $10 million Downtown Revitalization Initiative award. We have identified a simple yet transformative plan anchored by a public-private partnership involving software engineering firm SAMsix on Plattekill Avenue, centrally located in the Village of New Paltz. Using properties owned by the Village and SAMsix, we see an opportunity to develop a world-class TOURISM & ENGINEERING HUB to benefit local residents, visitors, and the regional economy by expanding 1) the number of high-paying engineering jobs in New Paltz; 2) the New Paltz Child Care center; 3) downtown parking; and 4) green infrastructure features to protect the Wallkill River. Having thus identified ENGINEERING, CHILDCARE, and TRAILS as our community’s foundational blocks, we are excited to make them the focus of New Paltz’s 2019 Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI) application. -

IHC Schedule for May 2014

1 Interstate Hiking Club Organized 1931 Affiliate of the NY-NJ Trail Conference Schedule of Hikes May 2014 through October 2014 IHC Web Page: www.interstatehikingclub.org IHC e-mail: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________ Interstate Hiking Club C/O Charles Kientzler 711 Terhune Drive Wayne, NJ 07470-7111 First Class Mail 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE INTERSTATE HIKING CLUB Who we are! The Interstate Hiking Club (IHC) is a medium-sized hiking club, organized in 1931. IHC has been affiliated with the NY/NJ Trail Conference, as a trail maintaining club, since 1931. Guests are welcome! An adult must accompany anyone under 18. No Pets allowed on IHC hikes. Where do we go? Most of our activities are centered in the NY/NJ area; some hikes, bicycle rides and canoe trips are farther away. The club occasionally sponsors trips in the Catskills and Pennsylvania. Our hikes are not usually accessible by public transportation. What do we do? Hikes, bicycle rides and canoe trips generally are scheduled for every Sunday, and some Fridays and Saturdays, as day-long outings. They are graded by difficulty of terrain, distance and pace. The Hiking grades are: Easy: These hikes are 3 to 5 miles in length and should have no significant hills. Moderate: These hikes are 5 to 8 miles and may take up to 5 hours, including time for trail lunch. They should not generally have multiple long steep hills, and should be at a moderate pace. Moderately Strenuous: These hikes are 5 to 8 miles with multiple steep hills or 8 miles or more which are mostly flat walking. -

Accelerating Growth, Spearheading Success

DUTCHESS ORANGE PUTNAM ROCKLAND SULLIVAN ACCELERATING ULSTER GROWTH, WESTCHESTER SPEARHEADING SUCCESS 2014 PROGRESS REPORT The Mid-Hudson Regional Economic Development Council Governor Andrew M. Cuomo A MESSAGE FROM THE CO-CHAIRS We are pleased to present the 2014 Mid-Hudson Regional Economic Development Council’s Progress Report, “Accelerating Growth, Spearheading Success.” Our focus over the last year has been to foster job growth in industry sectors critical to our communities, both through continued attention to past awardees, as well as through the identification of new opportunities for partnerships and strategic investment. Wherever possible, the Council has also aligned its work with the many state-wide initiatives and programs championed by Governor Andrew M. Cuomo, including Taste NY, START-UP NY, I Love NY, and the NY Community Rising Reconstruction Plan. The Council monitors the progress of all past awardees to ensure their success. It continues to support initiatives such as the Center for Global Advanced Manufacturing (an interregional 2012 Priority Project) that has opened machinist shops in both the Mid-Hudson and the Mohawk Valley regions. It also continues to promote opportunities for small business incubation, including BioInc at New York Medical College (a 2011 and 2012 Priority Project) and the NYS Cloud Computing and Analytics Center (a 2012 Priority Project), which showed a particular commitment to start-ups and MWBEs in the Mid-Hudson. In an effort to identify new strategy-aligned opportunities, our Council worked tirelessly to solicit projects from throughout the region and then to evaluate and select those that can truly make a difference to our economy. -

Fall 2018 Catalog

LIFELONG LEARNING INSTITUTE ✵ A T V A S S A R C O L L E G E CATALOG Fall 2018 We are an adult educational program affiliated with Vassar College offering a broad range of non-credit educational courses and activities to members 55 and over at a minimal cost. Classes are taught by volunteer members, retired and active faculty, and outside experts. LLI at Vassar College is a volunteer-run organization. It is designed for adults who love to learn and who wish to contribute to the larger community in their pursuit of knowledge. The LLI (Lifelong Learning Institute) at Vassar College believes that education is essential at every age. We are called on to continually expand our knowledge, so we might participate fully as citizens in our democracy. The education process is individually motivated as well as collaborative, with new ideas and new skills often introduced by others with a commitment to sharing. As we age, life experiences enhance our education. We are fortunate that members with unique perspectives, skills, and expertise are willing to share them with us. Vassar’s LLI is committed to forming a community that will advance the education of its members in a collaborative fashion. When we study, explore, and discuss together, we model engagement and expansion for each other. Most classes will be conducted in small groups to promote discussion, informed by the interests and knowledge of both volunteer instructors and LLI members. FALL 2018/SPRING 2019 membership is $140 per person, per year, non-transferable, and members can register for a maximum of three full courses per semester. -

Trail Walker

Keep Your Toes Warm Trails to Great Photos While Winter Hiking Robert Rodriguez Jr. reveals Why they get cold and how to some of his favorite places for avoid problems on the trail. photography in our region. READ MORE ON PAGE 11 READ MORE ON PAGE 7 Winter 2012 New York-New Jersey Trail Conference — Connecting People with Nature since 1920 www.nynjtc.org Awards Celebrate Cleaning Up Our Volunteers the Messes Trail Conference Awards are deter - The email from Sterling Forest mined by the Board of Directors, Trail Supervisors Peter Tilgner except for Distinguished Service and Suzan Gordon was dated Awards, which are determined by the October 31, 2011: Volunteer Committee. The following awards were announced at the Dear Sterling Forest Trail Maintainers, October 15, 2011 Annual Meeting in Today I was at the Tenafly Nature Center where I cleared, with hand tools, Ossining, NY. 0.4 mile of trail in about 4.5 hours. You all have your work cut out for you. I suggest RAYMOND H. TORREY AWARD you get to it pronto. Please note and let us Given for significant and lasting know the position of all blow-downs for contributions that protect hiking trails future chainsaw work. and the land upon which they rest. Thank you in advance for your effort doing this herculean task. We know you are All-around Volunteer JANE DANIELS, up to it. R I Mohegan Lake, NY E W E Jane Daniels, a well T Two days after the storm dubbed Snow - T E G known leader in the R tober tracked along much the same O E local, regional, and G route previously blazed by Tropical state trails community Storms Irene and Lee, Trail Conference for at least three Training & Recruitment volunteers were once again cleaning up decades, received the after Mother Nature.