A NON-SECULAR ANTHROPOCENE: Spirits, Specters and Other Nonhumans in a Time of Environmental Change AURA (Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Way of All Flesh

The Way of All Flesh Samuel Butler This eBook was designed and published by Planet PDF. For more free eBooks visit our Web site at http://www.planetpdf.com/. To hear about our latest releases subscribe to the Planet PDF Newsletter. The Way of All Flesh Chapter I When I was a small boy at the beginning of the century I remember an old man who wore knee-breeches and worsted stockings, and who used to hobble about the street of our village with the help of a stick. He must have been getting on for eighty in the year 1807, earlier than which date I suppose I can hardly remember him, for I was born in 1802. A few white locks hung about his ears, his shoulders were bent and his knees feeble, but he was still hale, and was much respected in our little world of Paleham. His name was Pontifex. His wife was said to be his master; I have been told she brought him a little money, but it cannot have been much. She was a tall, square-shouldered person (I have heard my father call her a Gothic woman) who had insisted on being married to Mr Pontifex when he was young and too good-natured to say nay to any woman who wooed him. The pair had lived not unhappily together, for Mr Pontifex’s temper was easy and he soon learned to bow before his wife’s more stormy moods. Mr Pontifex was a carpenter by trade; he was also at one time parish clerk; when I remember him, however, he had so far risen in life as to be no longer compelled to 2 of 736 The Way of All Flesh work with his own hands. -

The Use of Non-Human Primates in Research in Primates Non-Human of Use The

The use of non-human primates in research The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatherall FRS FMedSci Report sponsored by: Academy of Medical Sciences Medical Research Council The Royal Society Wellcome Trust 10 Carlton House Terrace 20 Park Crescent 6-9 Carlton House Terrace 215 Euston Road London, SW1Y 5AH London, W1B 1AL London, SW1Y 5AG London, NW1 2BE December 2006 December Tel: +44(0)20 7969 5288 Tel: +44(0)20 7636 5422 Tel: +44(0)20 7451 2590 Tel: +44(0)20 7611 8888 Fax: +44(0)20 7969 5298 Fax: +44(0)20 7436 6179 Fax: +44(0)20 7451 2692 Fax: +44(0)20 7611 8545 Email: E-mail: E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Web: www.acmedsci.ac.uk Web: www.mrc.ac.uk Web: www.royalsoc.ac.uk Web: www.wellcome.ac.uk December 2006 The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatheall FRS FMedSci December 2006 Sponsors’ statement The use of non-human primates continues to be one the most contentious areas of biological and medical research. The publication of this independent report into the scientific basis for the past, current and future role of non-human primates in research is both a necessary and timely contribution to the debate. We emphasise that members of the working group have worked independently of the four sponsoring organisations. Our organisations did not provide input into the report’s content, conclusions or recommendations. -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

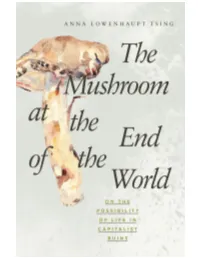

The Mushroom at the End of the World : on the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins / Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

Copyright © 2015 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu Jacket art: Homage to Minakata © Naoko Hiromoto All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The mushroom at the end of the world : on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins / Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-16275-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Human ecology. 2. Economic development—Environmental aspects. 3. Environmental degradation. I. Title. GF21.T76 2015 330.1—dc23 2014037624 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro and Syntax Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Enabling Entanglements vii PROLOGUE. AUTUMN AROMA I PART I What’s Left? II 1 | Arts of Noticing 17 2 | Contamination as Collaboration 27 3 | Some Problems with Scale 37 INTERLUDE. SMELLING 45 PART II After Progress: Salvage Accumulation 55 4 | Working the Edge 61 FREEDOM … 5 | Open Ticket, Oregon 73 6 | War Stories 85 7 | What Happened to the State? Two Kinds of Asian Americans 97 …IN TRANSLATION 8 | Between the Dollar and the Yen 109 9 | From Gifts to Commodities—and Back 121 10 | Salvage Rhythms: Business in Disturbance 131 INTERLUDE. TRACKING 137 PART III Disturbed Beginnings: Unintentional Design 149 11 | The Life of the Forest 155 COMING UP AMONG PINES … 12 | History 167 13 | Resurgence 179 14 | Serendipity 193 15 | Ruin 205 … IN GAPS AND PATCHES 16 | Science as Translation 217 17 | Flying Spores 227 INTERLUDE. -

Redacted - for Public Inspection

REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) AMC NETWORKS INC., ) Complainant, ) File No.:______________ ) v. ) ) AT&T INC., ) Defendant. ) TO: Chief, Media Bureau Deadline PROGRAM CARRIAGE COMPLAINT OF AMC NETWORKS INC. Tara M. Corvo Alyssia J. Bryant MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, FERRIS, GLOVSKY AND POPEO, P.C. 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Suite 900 Washington, DC 20004 (202) 434-7300 Scott A. Rader MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, FERRIS, GLOVSKY AND POPEO, P.C. Chrysler Center 666 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 (212) 935-3000 Counsel to AMC Networks Inc. August 5, 2020 REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................................................................. 5 1. Jurisdiction ........................................................................................................................ 5 2. AMCN ................................................................................................................................ 5 3. AT&T ................................................................................................................................. 6 4. AT&T’s Public Assurances During the Civil Antitrust Litigation .............................. 7 5. AT&T’s Discriminatory Conduct .................................................................................. -

Star Channels, July 15-21

JULY 15 - 21, 2018 staradvertiser.com COLLISION COURSE Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos on a new episode of Salvation. Airs Monday, July 16, on CBS Let’s bring over 70 candidates into view. Watch Candidates In Focus on ¶ũe^eh<aZgg^e-2' ?hk\Zg]b]Zm^bg_h%]^[Zm^lZg]_hknfl%oblbmolelo.org/vote JULY 16AUGUST 10 olelo.org MF, 7AM & 7PM | SA & SU, 7AM, 2PM & 7PM ON THE COVER | SALVATION Impending doom Multiple threats plague Armed with this new, time-sensitive informa- narrative. The actress notes that, while “the tion, Darius and Liam head to the Pentagon show is mostly about this impeding asteroid — season 2 of ‘Salvation’ and deliver the news to the Department of the sort of scaring, impending doom of that,” Defense’s deputy secretary, Harris Edwards people are “still living [their lives],” as the truth By K.A. Taylor (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five-0”). Harris makes it difficult for people to accept, which TV Media and DOD public affairs press secretary Grace leads them to set out a course of action that Barrows (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) have no reveals what’s truly important to them. Now cience fiction is increasingly becoming choice but to let these two skilled scientists that “the public knows” and “the secret is out science fact. The dreams of golden era into a covert operation called Sampson, re- ... people go bananas.” An event such as this Swriters and directors, while perhaps a vealing that the government was already well will no doubt “bring out the best” or to “bring bit exaggerated, are more prevalent now than aware of the threat but had chosen to keep it out the worst [in us],” but ultimately, Finnigan ever before. -

Sophie's World

Sophie’s World Jostien Gaarder Reviews: More praise for the international bestseller that has become “Europe’s oddball literary sensation of the decade” (New York Newsday) “A page-turner.” —Entertainment Weekly “First, think of a beginner’s guide to philosophy, written by a schoolteacher ... Next, imagine a fantasy novel— something like a modern-day version of Through the Looking Glass. Meld these disparate genres, and what do you get? Well, what you get is an improbable international bestseller ... a runaway hit... [a] tour deforce.” —Time “Compelling.” —Los Angeles Times “Its depth of learning, its intelligence and its totally original conception give it enormous magnetic appeal ... To be fully human, and to feel our continuity with 3,000 years of philosophical inquiry, we need to put ourselves in Sophie’s world.” —Boston Sunday Globe “Involving and often humorous.” —USA Today “In the adroit hands of Jostein Gaarder, the whole sweep of three millennia of Western philosophy is rendered as lively as a gossip column ... Literary sorcery of the first rank.” —Fort Worth Star-Telegram “A comprehensive history of Western philosophy as recounted to a 14-year-old Norwegian schoolgirl... The book will serve as a first-rate introduction to anyone who never took an introductory philosophy course, and as a pleasant refresher for those who have and have forgotten most of it... [Sophie’s mother] is a marvelous comic foil.” —Newsweek “Terrifically entertaining and imaginative ... I’ll read Sophie’s World again.” — Daily Mail “What is admirable in the novel is the utter unpretentious-ness of the philosophical lessons, the plain and workmanlike prose which manages to deliver Western philosophy in accounts that are crystal clear. -

Bonobos and Chimpanzees: How Similar Is Their Cognition and Temperament? a Large, Continuous, and Stable Population of Eastern C

window, the owner removed the monkey seconds after the killing and thus the eating of the prey was interrupted. Here, we report that pygmy marmosets in the Kristiansand Zoo in Norway reg- ularly kill and eat different species of healthy, free-living birds. We present what, to our knowl- edge, are the first systematic data collected on this behaviour. We describe the patterns of bird consumption by the monkeys. Pygmy marmosets are the smallest monkey species and thus their bird hunting behaviour is especially interesting since they are about the same size as the birds they prey upon. It has been proposed that humans are unique among primates for their ability to hunt prey that equals or exceeds their own body size. We discuss the implications that hunting of prey of equal body size by pygmy marmosets has for human evolution. Bonobos and Chimpanzees: How Similar Is Their Cognition and Temperament? Esther Herrmann Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany E-Mail: eherrman @ eva.mpg.de Key Words: Cognition · Temperament · Chimpanzees · Bonobos Despite the evolutionary closeness of bonobos (Pan paniscus) and chimpanzees (Pan tro- glodytes) , the behaviour of these two Pan species differs in crucial ways. A few key differences were revealed when both species were compared on a wide range of cognitive problems testing their understanding of the physical and social world (Herrmann et al., 2010). The tests of physi- cal cognition consisted of problems concerning space, quantity, tools and causality, while those of social cognition covered social learning, communication, and Theory of Mind tasks. A further comparison of bonobos and chimpanzees in two main temperamental components, reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart and Derryberry, 1981), was conducted to investigate other possible species differences. -

Planum Parietale of Chimpanzees and Orangutans: a Comparative Resonance of Human-Like Planum Temporale Asymmetry

THE ANATOMICAL RECORD PART A 287A:1128–1141 (2005) Planum Parietale of Chimpanzees and Orangutans: A Comparative Resonance of Human-Like Planum Temporale Asymmetry 1 2 3 PATRICK J. GANNON, * NANCY M. KHECK, ALLEN R. BRAUN, AND RALPH L. HOLLOWAY4 1Department of Otolaryngology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York 2Department of Medical Education, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York 3National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, Bethesda, Maryland 4Department of Anthropology, Columbia University, New York, New York ABSTRACT We have previously demonstrated that leftward asymmetry of the planum temporale (PT), a brain language area, was not unique to humans since a similar condition is present in great apes. Here we report on a related area in great apes, the planum parietale (PP). PP in humans has a rightward asymmetry with no correlation to the LϾR PT, which indicates functional independence. The roles of the PT in human language are well known while PP is implicated in dyslexia and communication disorders. Since posterior bifurcation of the syl- vian fissure (SF) is unique to humans and great apes, we used it to determine characteristics of its posterior ascending ramus, an indicator of the PP, in chimpanzee and orangutan brains. Results showed a human-like pattern of RϾLPP(P ϭ 0.04) in chimpanzees with a nonsig- nificant negative correlation of LϾR PT vs. RϾLPP(CCϭϪ0.3; P ϭ 0.39). In orangutans, SF anatomy is more variable, although PP was nonsignificantly RϾL in three of four brains (P ϭ 0.17). -

A Developmental Model for the Evolution of Language And

rilE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1979), 2, 367-408 Printed in the United States of Amenca A develOI)mental model for the evolution of language and intelliJgence in early hominids Sue Taylor Parker Department of Anthropology, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, Calif. 94928 Kathleen Rita Gibson Department of Anatomy, University of Texas, Dental Branch, Houston, Texas 77025 Abstract: This paper presents a model for the nature and adaptive significance of intelligence and language in early hominids based on comparative developmental, ecological, and neurological data. We propose that the common ancestor of the great apes and man displayed rudimentary forms of late sensorimotor and early preoperational intelligence similar to that of one- to four-year-old children. These abilities arose as adaptations for extractive foraging with tools, which requires a long postweaning apprenticeship. They were elaborated in the first hominids with the: shift to primary dependence on this feeding strategy. These first hominids evolved a protolanguage, similar to that of two-year-old human children, with which they could describe the nature and location of food and request help in obtaining it. The descendents of the first hominJids displayed intuitive intelligence, similar to that of four- to seven-year-old children, which arose as an adaptation for complex hunting involving aimed-missile throwing, stone-tool manufacture, animal butchery, food division, and shelter construction. The comparative developmental and paleontological data are consistent -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 19 July 2016 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Lameira, A. and Hardus, M.E. and Mielke, A. and Wich, S.A. and Shumaker, R.W. (2016) 'Vocal fold control beyond the species-specic repertoire in an orang-utan.', Scientic reports., 6 . p. 30315. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep30315 Publisher's copyright statement: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk 1 Vocal fold control beyond the species-specific repertoire in an orang-utan 2 3 4 Authors: Adriano R.