Politicising Fandom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrities As Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field

Celebrities as Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field Ellen Watts Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics 2018 Declaration I, Ellen Watts, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Ellen Watts September 17, 2018. 2 Abstract The ability of celebrities to become influential political actors is evident (Marsh et al., 2010; Street 2004; 2012, West and Orman, 2003; Wheeler, 2013); the process enabling this is not. While Driessens’ (2013) concept of celebrity capital provides a starting point, it remains unclear how celebrity capital is exchanged for political capital. Returning to Street’s (2004) argument that celebrities claim to speak for others provides an opportunity to address this. In this thesis I argue successful exchange is contingent on acceptance of such claims, and contribute an original model for understanding this process. I explore the implicit interconnections between Saward’s (2010) theory of representative claims, and Bourdieu’s (1991) work on political capital and the political field. On this basis, I argue celebrity capital has greater explanatory power in political contexts when fused with Saward’s theory of representative claims. Three qualitative case studies provide demonstrations of this process at work. Contributing to work on how celebrities are evaluated within political and cultural hierarchies (Inthorn and Street, 2011; Marshall, 2014; Mendick et al., 2018; Ribke, 2015; Skeggs and Wood, 2011), I ask which key factors influence this process. -

Rough Transcript, Check Against Delivery

1 ED MILIBAND THE ANDREW MARR SHOW 28TH JUNE 2020 ED MILIBAND MP Shadow Business Secretary (Rough transcript, check against delivery) AM: Welcome Mr Miliband. Was it right that Rebecca Long-Bailey was sacked? EM: It was. It’s important to explain why, because Rebecca is a very decent person, but the reason why there was a problem – the Maxine Peake interview, so the original interview Rebecca then tweeted, is not that it had a criticism of the state of Israel. I’m a big critic of what the Israeli government has done on a number of occasions. Instead it was a false criticism of the state of Israel linked – or rather, the Israeli Defence Force – linked to the death of George Floyd, wrongly, saying that somehow the tactics that killed George Floyd had been learnt from the Israelis. Let me explain why this is an important point. And the problem is that over the centuries when calamitous things have happened Jews have been blamed. And that’s why there was an anti-Semitism issue in that – in relation to this. And that’s why I believe Keir took the right decision. AM: Do you think that Rebecca Long-Bailey understood that? Do you think that she is anti-Semitic? EM: No, I don’t think she is anti-Semitic. I think she made a significant error of judgement. I know Rebecca well. I think she’s a decent person. But let me tell you what this underlines. This underlines the fact that Keir recognises the gravity of the hurt that has been caused to the Jewish community over the last few years by our failure to deal properly with issues of anti-Semitism. -

Completecoversonglist (Updated May 2020)

Classic/Vintage Rock Songs - 68 songs 1. Black Water - The Doobie Brothers 2. Jesus Is Just Alright - The Doobie Brothers 3. Listen To The Music - The Doobie Brothers 4. Long Train Runnin’ - The Doobie Brothers 5. No Time - The Guess Who 6. Share The Land - The Guess Who 7. Albert Flasher - The Guess Who 8. Undone - The Guess Who 9. Guns Guns Guns - The Guess Who 10. No Sugar Tonight / Good Times Bad Times Medley - The Guess Who / Led Zeppelin 11. Old Man - Neil Young 12. Ohio - CSN&Y 13. Suite Judy Blue Eyes - CSN&Y 14. Teach Your Children - CSN&Y 15. Find The Cost of Freedom - CSN&Y 16. Guinevere - CSN&Y 17. Helplessly Hoping - CSN&Y 18. Goodbye Stranger - Supertramp 19. Tiny Dancer - Elton John 20. Easy - The Commodores 21. Into The Mystic - Van Morrison 22. Ventura Highway - America 23. Sister Golden Hair - America 24. Two Tickets To Paradise - Eddie Money 25. Reelin’ In The Years - Steely Dan 26. Magic Carpet Ride - Steppenwolf 27. Whipping Post - The Allman Brothers 28. Can’t Buy Me Love - The Beatles 29. Revolution - The Beatles 30. Help - The Beatles 31. Serenade - Steve Miller Band 32. Fly Like An Eagle - Steve Miller Band 33. Jet Airliner - Steve Miller Band 34. Rock’n Me Baby - Steve Miller Band 35. Swingtown - Steve Miller Band 36. Dance, Dance, Dance - Steve Miller Band 37. Joker - Steve Miller Band 38. The Stake - Steve Miller Band 39. Black Magic Women - Santana 40. Night Moves - Bob Seger 41. Turn The Page - Bob Seger 42. Superstition - Stevie Wonder 43. Take It Easy - Eagles 44. -

Formal Minutes of the Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Formal Minutes of the Committee Session 2010-11 2 The Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National Assembly for Wales.) Current membership David T.C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) (Chair) Stuart Andrew MP (Conservative, Monmouth) Guto Bebb MP (Conservative, Pudsey) Alun Cairns MP (Conservative, Vale of Glamorgan), Geraint Davies MP (Labour, Swansea West) Jonathan Edwards, MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Mrs Siân C. James MP (Labour, Swansea East) Susan Elan Jones MP (Labour, Clwyd South) Karen Lumley MP (Conservative, Redditch) Jessica Morden MP (Labour, Newport East) Owen Smith MP (Labour, Pontypridd) Mr Mark Williams, MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/welsh_affairs_committee.cfm Committee staff The current staff of the Committee is Adrian Jenner (Clerk), Anwen Rees (Inquiry Manager), Jenny Nelson (Senior Committee Assistant), Dabinder Rai (Committee Assistant), Mr Tes Stranger (Committee Support Assistant) and Laura Humble (Media Officer). Contacts All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the Welsh Affairs Committee, House of Commons, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA. -

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013 Executive Summary Sixteen special advisers have gone on to become Cabinet Ministers. This means that of the 492 special advisers listed in the Constitution Unit database in the period 1979-2010, only 3% entered Cabinet. Seven Conservative party Cabinet members were formerly special advisers. o Four Conservative special advisers went on to become Cabinet Ministers in the 1979-1997 period of Conservative governments. o Three former Conservative special advisers currently sit in the Coalition Cabinet: David Cameron, George Osborne and Jonathan Hill. Eight Labour Cabinet members between 1997-2010 were former special advisers. o Five of the eight former special advisers brought into the Labour Cabinet between 1997-2010 had been special advisers to Tony Blair or Gordon Brown. o Jack Straw entered Cabinet in 1997 having been a special adviser before 1979. One Liberal Democrat Cabinet member, Vince Cable, was previously a special adviser to a Labour minister. The Coalition Cabinet of January 2013 currently has four members who were once special advisers. o Also attending Cabinet meetings is another former special adviser: Oliver Letwin as Minister of State for Policy. There are traditionally 21 or 22 Ministers who sit in Cabinet. Unsurprisingly, the number and proportion of Cabinet Ministers who were previously special advisers generally increases the longer governments go on. The number of Cabinet Ministers who were formerly special advisers was greatest at the end of the Labour administration (1997-2010) when seven of the Cabinet Ministers were former special advisers. The proportion of Cabinet made up of former special advisers was greatest in Gordon Brown’s Cabinet when almost one-third (30.5%) of the Cabinet were former special advisers. -

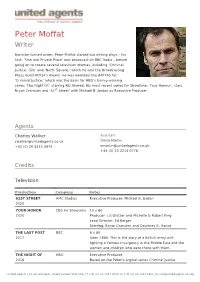

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

The Labour Party and the EU

15th September, 2016 The Labour Party and the EU It is verifiable that all of the problems that Britain has faced since 2010 have resulted almost entirely from decisions made by members of the New Labour; on behalf, and/or at the direction of the EU. Left wing Politicians who tried to con the electorate by disingenuously blaming all of our problems on the Conservative Party or the Banks at the time of the General Election. Today the British, that is to say those resident in Britain prior to the opening of the borders to Europe by New Labour (acting as agents for the EU) have become second class citizens in their own country in terms of access to jobs, housing, healthcare, social amenities, equality and quality of life. The problem with housing was never addressed by New Labour politicians, even though they were aware of the fact that there was a rapidly increasing population; which they were actually promoting. The model for this Utopian society that they were engineering, on behalf of the EU, was Multiculturalism, or to put it in context; introduced large scale segregation within existing settled communities. No proper provision was made for school places nor adequate healthcare. In fact, doctors were paid larger salaries in return for fewer working hours and were allowed to opt out of “after hours” provision – these politicians actually reduced capacity at the same time as increasing the population; an act tantamount to criminal mismanagement. These politicians on the Left would also like you to believe that they bear no responsibility for the effects of the financial crisis on Britain which led to a worldwide recession, making it much harder to get out of debt, and that it was all the fault of the banks. -

Social Care for Adults Aged 18–64

Analysis April 2020 Social care for adults aged 18–64 Omar Idriss, Lucinda Allen, Hugh Alderwick Acknowledgements We would like to thank Richard Humphries, Jessica Morris, Helen Buckingham, Joshua Kraindler, Anita Charlesworth, Nihar Shembavnekar, Charles Tallack, Ruth Thorlby, and Jennifer Dixon for their comments on earlier drafts of the paper. We are also grateful for the contribution of other Health Foundation staff. Errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors alone. Copyright acknowledgements Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. Incorporates data reproduced from www.skillsforcare.org.uk. When referencing this publication please use the following URL: https://doi.org/10.37829/HF-2020-P02 Social care for adults aged 18–64 is published by the Health Foundation, 8 Salisbury Square, London EC4Y 8AP ISBN: 978-1-911615-45-3 © 2020 The Health Foundation Contents Key points 2 Introduction 5 1: System context 8 2: Care needs 17 3: System performance 22 4: Outcomes 29 Discussion 35 References 39 Annex 1: Data sources 42 Key points • The adult social care system in England is broken and needs fixing. Debates about reform often focus on older people and the risk of them having to sell their homes to pay for social care. • What often gets missed are the issues facing younger adults needing social care – people aged 18–64 with learning disabilities, mental health problems and other social needs – and the care they need to support their independence and wellbeing. This publication presents analysis of publicly available data to understand the needs of younger adults in the social care system, how they differ from those of older people, and how these needs are changing. -

Im Sorry I Havent a Clue: the Best of Forty Years Pdf, Epub, Ebook

IM SORRY I HAVENT A CLUE: THE BEST OF FORTY YEARS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Barry Cryer,Graeme Garden,Jack Dee,Tim Brooke-Taylor,Stephen Fry | 288 pages | 01 Feb 2016 | Cornerstone | 9780099510543 | English | London, United Kingdom Im Sorry I Havent a Clue: the Best of Forty Years PDF Book Retrieved 26 April Dip into these helpfully illustrated pages and you'll find many of the words you use every day without ever realising Matt Parker. It's been a while" Tweet. Carl Giles. Once the pub had settled back down I decided it was time to get to the bottom of all this. A second collection of complete recordings of episodes from the early s, including two special, extended episodes. Subscription failed, please try again. Details I'm Sorry I Haven't A Clue - Three The third collection of the popular games, featuring a special clip show of highlights from previous episodes. British Sitcom Guide. Any Questions? Book collector. Following the death of chairman Humphrey Lyttelton , this special tribute to him, hosted by Stephen Fry was broadcast. Unfortunately there has been a problem with your order. The invariably single letter each week is from "A Mrs Trellis of North Wales ", one of the many prompts for a cheer from the audience, whose incoherent letters usually mistake the chairman for another Radio 4 presenter or media personality. The second collection of games and episodes, featuring the original cast, and a special documentary Everyman's Guide to Mornington Crescent. In recording, it has taken them many minutes to come up with the correct answer, most of which has to be edited out before broadcast. -

Im Sorry I Havent a Clue: V

IM SORRY I HAVENT A CLUE: V. 12 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK BBC,Barry Cryer,Graeme Garden,Humphrey Lyttelton,Tim Brooke-Taylor | 2 pages | 04 Nov 2010 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781408427194 | English | London, United Kingdom Im Sorry I Havent a Clue: v. 12 PDF Book The chairman apologised but explained that this was an unavoidable possibility and the guest left without having uttered a word. An extended version was released on DVD on 10 November Which will be followed by a nose-picking contest. Although there are twelve Clue shows broadcast per year these are the result of just six recording sessions, with two programmes being recorded back-to-back. Retrieved 16 January Since its inception 'Clue' has seen its success blossom from the impish son of 'I'm Sorry I'll Read That Again' to the big daddy of all panel games. Complete Quotes: how famous quotations ought to end. Series 60 View episodes Perennial antidote to panel games. Series 68 View episodes Jack Dee hosts the self-styled antidote to panel games. The chairman introduces the show with remarks such as:. Your email address will be added to our mailing list database, which will ensure that you are the first to hear about all BBC ISIHAC recording dates as well as touring shows. It was chosen by David Hatch. Sound Charades: charades without the benefit of mime. Series 72 homepage. Series 53 View episodes Perennial antidote to panel games. A few have been played only once, either because the joke works only once or because they were not particularly successful. -

Download PDF Version

Riots burn Fanshawe 3 Fanshawe speaks on Fleming 6 On the job hunt 14-22 Volume 44 Issue No. 26 March 26, 2012 www.fsu.ca/interrobang/ 2 NEWS Volume 44 Issue No. 26 March 26, 2012 www.fsu.ca/interrobang/ MARCH QUESTION EVENTS OF THE WEEK MON. 03-26 DO YOU 8 BALL POOL TOURNAMENT THINK THE Gamesroom – 5:00 -7:00PM $2 ADVANCE FLEMING RIOT LONDON KNIGHTS PLAYOFF GAME WILL HURT JLC – 7:00PM YOUR JOB $19 STUDENTS | $20 GUESTS TUES. 03-27 HUNT? FREE COMEDY NOONER: FEATURING: JOHN KI Forwell – NOON WED. 03-28 FREE INTERNET JOB SEARCH 10:00 - 11:30AM Register with Career Services Caitlin Montpetit for details “Yes I do! I’m coming from a FREE INTERVIEW SKILLS school with a bad reputation 2:30 - 4:00PM and I’m getting grouped Register with Career Services together with these rioters. I for details don’t even drink! TRIVIA NIGHT Out Back Shack – 8:00PM $5 per TEAM FIRST RUN FILM THE HUNGER GAMES Rainbow Cinemas $3.50 STUDENTS | $5 GUESTS THURS. 03-29 “YOU’VE FLAGGED!” BEEN – MARCH – 30 26 CREDIT: KIRSTEN ROSENKRANTZ FREE MUSIC NOONER: Sydney Bailey Students soak up the sun on the field behind Fanshawe College on March 21. FEATURING: SARAH SMITH ”It might because it made Forwell – NOON world news. It’s all over the world, so it might affect our 10 Things I Know About You... FRI. 03-30 chances.” FREE NEW MUSIC NIGHT Huiberts loves Fanshawe FEATURING: MONSTER TRUCK AND THE BAXTERS Rachel Huiberts is in her first Korn, Eminem, Disturbed, Jem, travelled? Out Back Shack – 9:30PM year of the Business Marketing Paramore, Foo Fighters, Limp Throughout Ontario and eastern program. -

Social Care Provision in the UK and the Role of Carers Debate on 24 June 2021 Author: Thomas Brown Date Published: 17 June 2021

Library Briefing Social care provision in the UK and the role of carers Debate on 24 June 2021 Author: Thomas Brown Date published: 17 June 2021 On 24 June 2021, the House of Lords is due to debate a motion moved by Baroness Jolly (Liberal Democrat) that “this House takes note of social care provision in the United Kingdom, and the role of carers in that provision”. The term ‘social care’ covers a wide range of support provided to children, young people, and working age and older adults, as well as their carers. This support can be provided formally, either by local authorities, private companies, charities, or other bodies; informally, by family members, friends, or neighbours; or through a combination of these. Although in practice it can include support for both children and adults, the term is often used as shorthand for adult social care in debates on the subject. Social care is a devolved matter and provision differs across the UK: • In England, local authorities hold both responsibility for children’s social care and a formal role in assessing the need for and commissioning adult social care. Differences in budgets, costs and local authorities having discretion to provide adult care services to individuals outside of eligibility thresholds have led to variations across the country. The adult social care system has been the focus of longstanding calls for reform. The UK Government has said it will bring forward proposals to “fix” adult social care in England later this year. • In Scotland, where an entitlement to free personal social care has been in place since 2002, the Scottish Government has pledged to create a National Care Service.