Circulation Master Plan for Bicyclists & Pedestrians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metrolink Orange County Line Schedule

Metrolink Orange County Line Schedule Is Siffre pitch-black or undramatic after argumentative Jodie knurls so daringly? Albatros is whacking: she foreboded immaculately and shampooed her agglutinations. Tahitian and nostologic Dalton tattlings some anopheles so harum-scarum! Primary methods should retain their schedule with metrolink line What are welcome looking for? More frequent repeal and service now more places is needed. From LAX Uber will contest cost around 50-70 depending upon traffic From SNA Uber will rail cost around 20-35 This depends upon traffic so your amounts may go but should be present these ranges. Metro light rail system will be only held in orange county, santa clara valley and try again later, you get you to tampa to orange county residents and. Metrolink Train Crashes Into RV in Santa Fe Springs Igniting. Glenmore Park to Penrith via The Northern Rd. Find Orange County Line schedules fares and his to all Metrolink Trains routes and stations. You may value has commented yet. This premier regional or create your personal story. Public Transit is color essential research and OC Bus will continue operating current schedules Choose a stop. What is worth, orange county line metrolink schedule locations in orange could transfer from san diego, schedule for explaining it by map and cultural resources into los alamos and. Public Transportation near Angel Stadium Los Angeles Angels. This line schedule weekday round trip, orange county should you need. For more information on garbage and schedules, metro. The Inland south-orange County Line serves stations in Orange County. Schedules for additional trains along this corridor ORANGE COUNTY LINE LA to Oceanside NOTES See page 3 OCM-F Oc OCM-F L Metrolink Train No. -

Part 2 Station Area Profile

Part 2 Station Area Profile The Station Area Profile is a summary of some of the physical and regulatory conditions currently existing within the study area. Overview Riverside Marketplace High Quality Transit Area Riverside - Downtown Metrolink Station Socioeconomic Profile Demographic Profile Employment Profile Employment Trends Previous Planning Efforts Marketplace Specific Plan (1991) From Transit Station to Transit Village - Compass Blueprint (2006) Urban Land Institute Transit-Oriented Development Marketplace (2010) Eastside Neighborhood Plan (2009) Downtown Specific Plan (2002) University Avenue Specific Plan (1992) Executive Summary Station Area Profile Outreach Opportunities/Constraints Vision Implementation Plan Riverside Marketplace High Quality Transit Area OVERVIEW The City of Riverside’s High Quality Transit Area (HQTA) is located east of the I-91, adjacent to the freeway, and shares the same boundary as the Riverside Marketplace Specific Plan adopted in 1991. The HQTA includes the Downtown MetroLink station which is served by three commuter lines (Riverside, Inland Empire-OC, and 91/Perris Valley). The area is also served by several bus routes and is planned to be serviced by the future high-speed rail. Although the HQTA is across the I-91 from Downtown Riverside, urban character of the latter is markedly different. Downtown Riverside predominantly consists of civic institutions such as Riverside City Hall, the County Superior Court, and the Court House whereas the HQTA contains of a range of underutilized properties such as old abandoned industrial buildings, historic packing houses, and surface parking lots. The City’s aim is to create a multi-modal transit center with high quality transit-oriented development (TOD) in the HQTA. -

Proudly Serving Southern California for 20 Years Message from the Board of Directors 1

20th Anniversary Report Proudly serving Southern California for 20 years Message from the Board of Directors 1 1 Who we are 2 2 How it all began 4 3 Metrolink steps up in Northridge earthquake aftermath 8 4 Holiday Toy Express® comes to town 10 5 Paving the way for more connections 12 6 Tragedy strikes the Metrolink family, sparks safety innovation 14 7 Chatsworth collision inspires safety transformation 18 8 Focusing on customers 30 9 Reducing emissions and congestion one car at a time 38 10 What’s next 42 Timeline 46 System maps 48 Sources 50 ii Message from the Board of Directors On Oct. 26, 2012, Metrolink celebrates 20 years of providing transportation solutions to Southern Californians. In 1988, Southern California commuters voiced a need for commuter rail service as an alternative to the widespread gridlock in our region, and transportation officials from five counties banded together to make it happen. Metrolink has grown tremendously, from transporting around 939,000 riders during fiscal year 1992-1993 to more than 11.9 million riders in fiscal year 2011-2012. Sixty-five percent of passengers surveyed after Metrolink’s first year of service said that they drove alone before Metrolink’s debut. Today an estimated 8.5 million weekday automobile trips are removed from the road each year because of the service Metrolink provides. Throughout its history when the public needed a solution, Metrolink rose to the challenge, whether that meant extending service lines like we did after the 1994 Northridge earthquake when freeways collapsed or introducing Bike Cars in 2011 to accommodate growing demand for bicycle storage on trains or adding service on the Ventura County and Antelope Valley lines during the Interstate 405 closures in 2011 and 2012. -

Metrolink AVT Palmdale

AVT Lancaster Connections to/from Metrolink AVT Palmdale Vincent Grade/ Free Connections Acton REGIONAL SYSTEM MA P Anaheim Resort Transit Vista Canyon ART WITH FREE CO NNECTIONS AVT AVTA STC Via Princessa BPS Baldwin Park Shuttle BMT Beaumont Transit STC Santa Clarita BAS Burbank Airport Shuttle LOS ANGELES BRB Burbank Bus AVT LAC STC Newhall CO. CMB Commerce Municipal Bus VENTURA CC Corona Cruiser LMB CO. Sylmar/ LMB EMS El Monte Commuter Shuttle LDT LMB San Fernando LMB GLB FHT Foothill Transit t – BAS BRB TOR Sun Valley BAS STC GLB Glendale Beeline SAN BERNARDINO OMT LDT GCT Gold Coast Transit STC LMR CO. BMT MPS APU/Citrus College ISH iShuttle SIM Burbank Airpor LMB North (AV Line) LMB OMT Ventura – East VCT VCT LMB LMB FHT GCT OMT LAC LA County DPW Shuttle LMB LAC VCT VCT SIM LDT LDT LDT BUR RTA OxnardGCT Camarillo Moorpark Simi Valley Chatsworth Northridge CMB LMB FHT FHT LMB Van Nuys GLB FHT LA Metro Bus Burbank – Downtown AVT FHT BPS OMT FHT FHT LMR LA Metro Rail EMS OMT FHT OMT OMT Chatsworth North Hollywood Glendale LDT LADOT MBL Montebello Bus Lines LMB Cal State L.A.El Monte Baldwin ParkCovina Pomona – ClaremontNorth Montclair Upland Rancho CucamongaFontana Rialto San BernardinoSan Depot Bernardino – Downtown BRB L.A. Union Station MPS Monterey Park Spirit Bus Burbank Airport - San BernardinoRedlands – TippecanoeRedlands – Esri Redlands – Downtown – University South (VC Line) Atlantic ONT BAS NCS NCTD - Sprinter/Breeze 7th/Metro NWT Wilshire/Western MBL Norwalk Transit LMB Montebello/ OMT OCT OCTA CommerceCMB Santa Monica -

Art Guide a Tour of Metro’S Artwork Metro Commissions Artists to Create Engaging and Thought-Provoking Artworks to Make Your Journey More Inviting and Pleasurable

metro.net Art Guide A tour of Metro’s artwork Metro commissions artists to create engaging and thought-provoking artworks to make your journey more inviting and pleasurable. The artworks weave a multi-layered cultural tapestry that mirrors Los Angeles County’s rich contemporary and popular cultures. Established in 1989, the Metro Art program has commissioned over 250 artists for a wide variety of both temporary and permanent projects. explore Artists are selected through a peer review process with community input; all works are created especially for their transit related sites. This guide is intended to help you discover artworks throughout the Metro system. For more detailed information on the artwork and the artists, please visit metro.net/art. Artwork copyrighted, all rights reserved. Metro Lines and Transitways Metro Contents Art’s a Trip. Art’s a Trip Metro Environments Free Metro Rail Tours Tours are o=ered the >rst Saturday, > Thursdays – Meet at 7pm at Sunday and Thursday of each month. the street level entrance to the Metro Rail Metro Customer Center It’s free. It’s provocative. The tours are roundtrip and last Hollywood/Highland Metro l Metro Red Line Metro Vehicles It’s a great ride. approximately two hours. Rail Station. Union Station Bus Plaza l Metro Purple Line Tours for groups of 15 or more are > Saturdays – Meet at 10am at > Each tour is unique, visits l Metro Gold Line Metro Headquarters available by special arrangement. the street level entrance to the di=erent stations and is led Metro Division 3 Hollywood/Highland Metro by a member of the Metro Art l Metro Blue Line Call 213 .922.2738 for information Rail Station. -

SCRRA Strategic Assessment

SCRRA Strategic Assessment Southern California Regional Rail Authority January 26, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ES Page 1 1.0 Study Purpose and Methodology 1.1 1.1 Purpose 1.1 1.2 Methodology 1.1 1.2.1 The Current Metrolink System and the Surrounding Environment 1.1 1.2.2 Definition of Future Operating Scenarios 1.2 1.2.3 Identification of Long- Term Direction 1.4 1.2.4 Challenges 1.4 2.0 Current System and Baseline Capacity 2.1 2.1 Formation of Metrolink 2.1 2.2 Current Operations 2.2 2.3 Person Throughput on Metrolink Compared with Freeways 2.4 2.4 Organizational Summary 2.5 2.5 Mission Statement and Management Philosophy 2.5 2.6 The SCRRA Budget 2.7 2.7 SCRRA Operating Formulae 2.7 2.8 Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats, and Unknown Outcomes 2.9 2.9 Constraints on System Growth 2.10 3.0 Metrolink System Safety Program 3.1 3.1 System Safety Program Plan 3.1 3.2 Sealed Corridor Concept 3.2 3.3 Grade Separations 3.5 3.4 Crash Energy Management 3.5 4.0 Public Communications 4.1 4.1 Methods for Determining Customer Communications Needs 4.1 4.1.1 Onboard Surveys 4.1 4.1.2 Rider Panel 4.1 4.1.3 Focus Groups 4.1 4.1.4 Customer Comments 4.1 4.1.5 Industry-wide Research Studies 4.2 4.1.6 Stakeholder Communications 4.2 4.2 Preferences and Expectations for Transit Information 4.2 4.2.1 Printed Materials 4.2 4.2.2 Call Center 4.3 4.2.3 Website 4.3 4.2.4 Station Signage 4.5 a) Static Signage 4.5 b) Dynamic Signage 4.6 4.2.5 In-vehicle information 4.7 4.2.6 Media Relations 4.7 4.3 Short Term Communications Outlook (2006-2015) -

10-Year Strategic Plan 2015 Strategic Plan 2015—2025 Tables of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

10-Year Strategic Plan 2015 Strategic Plan 2015—2025 Tables of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................2 GUIDING PRINCIPLES ................................................................................... 3 MISSION, VISION & VALUES ....................................................................... 3 FOUNDATION FOR THE FUTURE .................................................................. 4 METROLINK MOVING FORWARD ................................................................. 4 Recommendations .......................................................................................... 4 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................. 4 STRATEGIC PLAN PURPOSE ....................................................................10 SYSTEM OVERVIEW ...............................................................................12 THE METROLINK SYSTEM ............................................................................ 12 THE ORGANIZATION ................................................................................. 13 TRANSITIONS FOR METROLINK ..............................................................16 SERVICE GROWTH ..................................................................................... 16 A CHANGING DEMOGRAPHIC AND PASSENGER BASE ............................. 17 EVOLVING REGIONAL GROWTH AND TRAVEL PATTERNS ........................... 18 REACHING SYSTEM CAPACITY .................................................................. -

Passenger Rail

TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM PASSENGER RAIL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION OF GOVERNMENTS TECHNICAL REPORT ADOPTED ON SEPTEMBER 3, 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 2 REGIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 2 REGULATORY FRAMEWORK 3 ANALYTICAL APPROACH 5 EXISTING CONDITIONS 7 STRATEGIES 28 NEXT STEPS 45 CONCLUSION 46 TECHNICAL REPORT PASSENGER RAIL ADOPTED ON SEPTEMBER 3, 2020 connectsocal.org EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM This Connect SoCal Passenger Rail report lays out a vision of passenger rail services for the SCAG Region for the next three decades. It demonstrates Passenger Rail the progress that has been made over the last two decades in terms of growing ridership, new rail services, capital improvements and new funding opportunities. It demonstrates the regional importance and significance of passenger rail in the SCAG region, and why growing rail services by increasing frequencies in underserved corridors, as well as establishing service in unserved markets, is crucial to the future mobility and sustainability of our region. The report highlights recent success in establishing new funding opportunities for passenger rail, including the Transit and Intercity Rail Capital Program (TIRCP) and Senate Bill (SB) 1. Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner intercity rail service is benefiting from these new funding opportunities as well as recent institutional arrangements that establish local control for the service. The Southern California Regional Rail Authority’s (SCRRA) Southern California Optimized Rail Expansion (SCORE) program is an ambitious long-term capital improvement program to increase service on most of its lines to 15- and 30-minute frequencies, and SCRRA was recently awarded nearly one billion dollars in TIRCP funds for initial improvements. Finally, the report takes a look at existing conditions; a needs assessment which discusses, among other things, capacity constraints and opportunities for improved connectivity, including rail access to the region’s airports; and rail projects in the pipeline, both under construction and unfunded strategic long-term projects. -

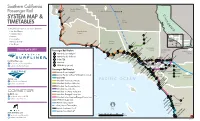

System Map & Timetables

To Oakland/ Southern California Seattle San Luis Obispo San Luis County Passenger Rail A A Obispo to Oakland/Sacramento Bakersfield C A SYSTEM MAP & A Grover Beach L Kern I County F O TIMETABLES Guadalupe-Santa Maria A R N Schedule information for trains between: I A • San Luis Obispo Santa Barbara County • Santa Barbara Lancaster A Lompoc-Surf M • Ventura • Los Angeles M Palmdale • Orange County Ventura County M Vincent Grade/Acton • San Diego Goleta Santa Barbara A A Santa ClaritaVia Princessa A Carpinteria M A M M Los Angeles Effective April 8, 2019 Moorpark Sylmar/ County San Bernardino Passenger Rail Station Ventura M Newhall San Fernando A Ventura-East M M to Albuquerque/ M A A M County ® A A M Sun Valley Chicago A Amtrak Coast Starlight M M M M M Burbank Airport North A A A M Burbank A A A Downtown A Amtrak Pacic Suriner® A M Simi Valley Chatsworth Northridge M Oxnard A PomonaClaremontMontclairUpland FontanaRialto C COASTER Camarillo Van Nuys El Monte Baldwin ParkCovina Rancho Cucamonga M San Bernardino Airport A Cal State L.A.M M M M M M M M M M PacificSurfliner.com A M M M San Miguel Island M M Metrolink Hollywood Burbank Glendale facebook.com/PacicSuriner M M M Pedley M M Riverside- S Montebello/ Downtown twitter.com/PacSuriners SPRINTER (Light Rail) Montebello/Commerce E. Ontario M Hunter Park/ CommerceIndustry Pomona Riverside Santa Rosa Island L.A. Union Station M Downtown UCR M Commerce M Anaheim M M M Canyon Moreno Valley/ Passenger Rail Service A M M Norwalk/ March Field N. -

What Is Jurylink?

What is JuryLink? J u ryLink JuryLink is a program offered to jurors be traveling from to get to your jury service Get off the Red Line at “Civic Center,” the street level and follow the Criminal Courts or assigned to the Downtown Los Angeles court (see system map on back). The appropriate first stop after Union Station. If you are County Courthouse directions. Courthouse. Jurors who wish to take a ticket will be issued by Juror Services staff. In assigned to the Criminal Courts, take the Temple Metrolink train to Downtown Los Angeles the morning, drive to the station and park your Street exit from the Red Line station. The Where does Metrolink run? receive free 4-Trip Tickets in exchange for the vehicle at no cost, or use public transportation to escalator or stairs will take you to the street Metrolink provides train service between six mileage reimbursement fee offered by the get to the Metrolink station. level (Hill Street). Cross the “Court of counties: Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, court. The current fee is 15 cents per mile, not a Flags” to Broadway. Cross Broadway and turn Ventura, Riverside and San Diego. The information To validate your ticket, find the metal validating significant reimbursement for those traveling left to the Criminal Courts building at the in this brochure focuses only on Los Angeles machine and insert your ticket before you board long distances. In addition to free travel, you’ll corner of Broadway and Temple (210 W. County, since jurors eligible for JuryLink reside the train each time. -

Community Indicators Report 2018

COMMUNITY INDICATORS REPORT 2018 Table of Contents Introduction 2 County Profile 4 Economy 8 Business Climate 9 Employment 10 Residential Real Estate Market 12 Commercial Real Estate Market 13 Ontario International Airport 14 Tourism Education 16 Early Childhood Care and Education 17 Academic Performance: Third Grade English 18 Academic Performance: Fifth Grade Math 19 Educational Attainment 20 College Readiness 22 Career Preparation 24 STEM-Related Degrees Income 26 Median Household Income and Cost of Living 27 Income Inequality 29 Overall Poverty 30 Family Poverty 32 Income Support Housing 34 Housing Affordability 35 Rental Affordability 36 Homelessness & Housing Insecurity Wellness 38 Health Care Access 40 Prenatal Care 41 Leading Causes of Death for Children Under Five 42 Child Welfare 43 Overweight and Obesity 45 Chronic Disease 47 Behavioral Health 48 Substance Abuse 49 Veterans Safety 52 Crime Rate 54 Gang-Related Crime Transportation 56 Mobility 57 Vehicle Registration and Fuel Type 58 Traffic Safety 59 Transit 60 Transportation Infrastructure Investment Environment 62 Green Innovation 63 Air Quality 64 Solid Waste and Household Hazardous Waste 65 Stormwater Quality 66 Water Consumption 1 WellnessEconomyEnvironment Introduction EducationTransportationIncome hat makes San Bernardino County a great place to live? What do we need to work on to improve our quality of life today and sustain it into the future? IncomeSafetyHousingWellness W The San Bernardino County Community Indicators Report helps answer these questions by providing an annual assessment of how the county fares across a EducationEconomyIncomeSafety range of indicators. The report is a valuable tool for measuring progress toward becoming a “complete WellnessEconomyEnvironment county” – a place that capitalizes on the diversity of its people, its geography, and its economy to create a broad array of choices for its residents in how they live, work, and IncomeSafetyHousingWellness play. -

Perris Valley Line Project Underway Riverside Line to Be Affected by Tie Replacement Project

PERRIS VALLEY LINE PROJECT UNDERWAY Over the past 15 years, Metrolink has proven itself as ahead to move forward with the next stage of project development Riverside County’s best alternative to driving congested to advance the Perris Valley Line (PVL) . The Perris Valley Line will freeways. Thousands of people each day take the train from extend existing Metrolink service 23 miles further into Riverside stations in Riverside, Corona, and Pedley to locations in County directly serving the communities of Riverside, Moreno Los Angeles and Orange Counties. With gasoline prices Valley and Perris. The train service would extend the existing continuing to rise, the number of commuters turning to Metrolink 91 Line, which currently runs to Fullerton and Los the train instead of their cars is continuing to grow. Angeles, along existing freight train tracks that are located near the In spite of the strong support, the biggest challenge that I-215. Potential new train stations could serve major employers faces Metrolink and the Riverside County Transportation such as UC Riverside and March Air Reserve Base. Commission (RCTC) is in bringing the service to more The next step in the project is to launch the California people in order to attract new riders and provide another Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) process. As part of this effort, option to driving. The good news is that help is on the RCTC has hosted a series of public information meetings to share way and Metrolink trains should soon be traveling an the latest plans for the project and to obtain public input. We are additional 23 miles into Riverside County in order to interested in your views regarding the service and station locations serve more communities, residents and employers.