I 0 143 1110

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zelenka I Penitenti Al Sepolchro Del Redentore, Zwv 63

ZELENKA I PENITENTI AL SEPOLCHRO DEL REDENTORE, ZWV 63 COLLEGIUM 1704 COLLEGIUM VOCALE 1704 VÁCLAV LUKS MENU TRACKLIST TEXTE EN FRANÇAIS ENGLISH TEXT DEUTSCH KOMMENTAR ALPHA COLLECTION 84 I PENITENTI AL SEPOLCHRO DEL REDENTORE, ZWV 63 JAN DISMAS ZELENKA (1679-1745) 1 SINFONIA. ADAGIO – ANDANTE – ADAGIO 7’32 2 ARIA [DAVIDDE]. SQUARCIA LE CHIOME 10’08 3 RECITATIVO SECCO [DAVIDDE]. TRAMONTATA È LA STELLA 1’09 4 RECITATIVO ACCOMPAGNATO [MADDALENA]. OIMÈ, QUASI NEL CAMPO 1’21 5 ARIA [MADDALENA]. DEL MIO AMOR, DIVINI SGUARDI 10’58 6 RECITATIVO SECCO [PIETRO]. QUAL LA DISPERSA GREGGIA 1’38 7 ARIA [PIETRO]. LINGUA PERFIDA 6’15 8 RECITATIVO SECCO [MADDALENA]. PER LA TRACCIA DEL SANGUE 0’54 4 MENU 9 ARIA [MADDALENA]. DA VIVO TRONCO APERTO 11’58 10 RECITATIVO ACCOMPAGNATO [DAVIDDE]. QUESTA CHE FU POSSENTE 1’25 11 ARIA [DAVIDDE]. LE TUE CORDE, ARPE SONORA 8’31 12 RECITATIVO SECCO [PIETRO]. TRIBUTO ACCETTO PIÙ, PIÙ GRATO DONO RECITATIVO SECCO [MADDALENA]. AL DIVIN NOSTRO AMANTE RECITATIVO SECC O [DAVIDDE]. QUAL IO SOLEVA UN TEMPO 2’34 13 CORO E ARIA [DAVIDDE]. MISERERE MIO DIO 7’07 TOTAL TIME: 71’30 5 MARIANA REWERSKI CONTRALTO MADDALENA ERIC STOKLOSSA TENOR DAVIDDE TOBIAS BERNDT BASS PIETRO COLLEGIUM 1704 HELENA ZEMANOVÁ FIRST VIOLIN SUPER SOLO MARKÉTA KNITTLOVÁ, JAN HÁDEK, EDUARDO GARCÍA, ELEONORA MACHOVÁ, ADÉLA MIŠONOVÁ VIOLIN I JANA CHYTILOVÁ, SIMONA TYDLITÁTOVÁ, PETRA ŠCEVKOVÁ, KATERINA ŠEDÁ, MAGDALENA MALÁ VIOLIN II ANDREAS TORGERSEN, MICHAL DUŠEK, LYDIE CILLEROVÁ, DAGMAR MAŠKOVÁ VIOLA LIBOR MAŠEK, HANA FLEKOVÁ CELLO ONDREJ BALCAR, ONDREJ ŠTAJNOCHR -

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

Musica Lirica

Musica Lirica Collezione n.1 Principale, in ordine alfabetico. 891. L.v.Beethoven, “Fidelio” ( Domingo- Meier; Barenboim) 892. L.v:Beethoven, “Fidelio” ( Altmeyer- Jerusalem- Nimsgern- Adam..; Kurt Masur) 893. Vincenzo Bellini, “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” (Pavarotti- Rinaldi- Aragall- Zaccaria; Abbado) 894. V.Bellini, “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” (Pavarotti- Rinaldi- Monachesi.; Abbado) 895. V.Bellini, “Norma” (Caballé- Domingo- Cossotto- Raimondi) 896. V.Bellini, “I Puritani” (Freni- Pavarotti- Bruscantini- Giaiotti; Riccardo Muti) 897. V.Bellini, “Norma” Sutherland- Bergonzi- Horne- Siepi; R:Bonynge) 898. V.Bellini, “La sonnanbula” (Sutherland- Pavarotti- Ghiaurov; R.Bonynge) 899. H.Berlioz, “La Damnation de Faust”, Parte I e II ( Rubio- Verreau- Roux; Igor Markevitch) 900. H.Berlioz, “La Damnation de Faust”, Parte III e IV 901. Alban Berg, “Wozzeck” ( Grundheber- Meier- Baker- Clark- Wottrich; Daniel Barenboim) 902. Georges Bizet, “Carmen” ( Verret- Lance- Garcisanz- Massard; Georges Pretre) 903. G.Bizet, “Carmen” (Price- Corelli- Freni; Herbert von Karajan) 904. G.Bizet, “Les Pecheurs de perles” (“I pescatori di perle”) e brani da “Ivan IV”. (Micheau- Gedda- Blanc; Pierre Dervaux) 905. Alfredo Catalani, “La Wally” (Tebaldi- Maionica- Gardino-Perotti- Prandelli; Arturo Basile) 906. Francesco Cilea, “L'Arlesiana” (Tassinari- Tagliavini- Galli- Silveri; Arturo Basile) 907. P.I.Ciaikovskij, “La Dama di Picche” (Freni- Atlantov-etc.) 908. P.I.Cajkovskij, “Evgenij Onegin” (Cernych- Mazurok-Sinjavskaja—Fedin; V. Fedoseev) 909. P.I.Tchaikovsky, “Eugene Onegin” (Alexander Orlov) 910. Luigi Cherubini, “Medea” (Callas- Vickers- Cossotto- Zaccaria; Nicola Rescigno) 911. Luigi Dallapiccola, “Il Prigioniero” ( Bryn-Julson- Hynninen- Haskin; Esa-Pekka Salonen) 912. Claude Debussy, “Pelléas et Mélisande” ( Dormoy- Command- Bacquier; Serge Baudo). 913. Gaetano Doninzetti, “La Favorita” (Bruson- Nave- Pavarotti, etc.) 914. -

Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos - A survey of the major recordings by Ralph Moore Ariadne auf Naxos is less frequently encountered on stage than Der Rosenkavalier or Salome, but it is something of favourite among those who fancy themselves connoisseurs, insofar as its plot revolves around a conceit typical of Hofmannsthal’s libretti, whereby two worlds clash: the merits of populist entertainment, personified by characters from the burlesque Commedia dell’arte tradition enacting Viennese operetta, are uneasily juxtaposed with the claims of high art to elevate and refine the observer as embodied in the opera seria to be performed by another company of singers, its plot derived from classical myth. The tale of Ariadne’s desertion by Theseus is performed in the second half of the evening and is in effect an opera within an opera. The fun starts when the major-domo conveys the instructions from “the richest man in Vienna” that in order to save time and avoid delaying the fireworks, both entertainments must be performed simultaneously. Both genres are parodied and a further contrast is made between Zerbinetta’s pragmatic attitude towards love and life and Ariadne’s morbid, death-oriented idealism – “Todgeweihtes Herz!”, Tristan und Isolde-style. Strauss’ scoring is interesting and innovative; the orchestra numbers only forty or so players: strings and brass are reduced to chamber-music scale and the orchestration heavily weighted towards woodwind and percussion, with the result that it is far less grand and Romantic in scale than is usual in Strauss and a peculiarly spare ad spiky mood frequently prevails. -

RENATA TEBALDI Soprano

1958 Eightieth Season 1959 UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor Fourth Concert Thirteenth Annual Extra Series Complete Series 3252 RENATA TEBALDI Soprano GIORGIO F AVARETTO at the Piano TUESDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 1 0 , 1959, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, M ICHIGAN PROGRAM Aria, "Ab! spietato" from Amadigi HANDEL 1Jna ragazza che non e pazza GALUPPI Caldo sangue SCARLATTI Canzonetta SCARLATTI Ridente la calma MOZART 1J n mota di gioia MOZART La Regata Veneziana ROSSINI Anzoleta prima della regata Anzoleta durante la regata Anzoleta dopo Ia regata Vaga luna che inargenti BELLINI Per pieta bell' idol mio BELLINI INTERMISSION M'ama, non m'ama MASCAGNI Notte RESPIGHI Ninna nanna di 1Jliva . PIZZETTI o luna cbe fa' lume DAVICO A vuccbella TOSTI "Salce, salce" "Ave Maria" } from Otello VERDI London Ifrr Records The Steinway is the official piano of the U11iversity Musical Society A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS PROGRAM NOTES "Ah, spietato," from Amadigi HANDEL Ah, cruel one, are you not moved by the constant affection that makes me languish for you! Una ragazza che non e pazza GALUPPI A girl who is not crazy knows not to let her chance pass. You know it and you will understand me. Even the little ewe lamb and dove would look for a companion. Why would not a girl! Caldo sangue SCARLATTI Hot hlood, hot blood, that flows over my breast, give testimony of my love and devotion to my father as I die. -

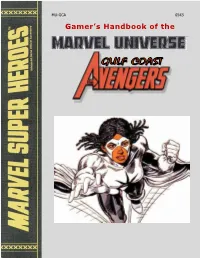

Gamer's Handbook Of

MU-GCA 6543 Gamer’s Handbook of the Unofficial Game Accessory Gamer’s Handbook of the Contents Gulf Coast Avengers Sea Urchin ................................................ 67 Captain Marvel ............................................ 2 Sunstroke .................................................. 69 Devilray ...................................................... 4 Sunturion .................................................. 70 Force II ...................................................... 6 Tezcatlipoca .............................................. 72 Pig Iron ...................................................... 8 Torpedo II ............................................... 74 Swamp Fox ............................................... 10 White Star [Estrella Blanca] ........................ 76 Thorn ....................................................... 12 Wildthing .................................................. 78 Weaver ..................................................... 14 Zoo Crew .................................................. 80 Texas Rangers Dust Devil ................................................. 16 Firebird ..................................................... 18 Lonestar ................................................... 20 Longhorn .................................................. 22 Red Wolf ................................................... 24 Texan ....................................................... 26 Bulwark .................................................... 28 Candra .................................................... -

Wwciguide January 2017.Pdf

Air Check The Guide Dear Member, The Member Magazine for Happy New Year! January is always a very exciting month for us as we often debut some of the WTTW and WFMT Renée Crown Public Media Center most highly-anticipated series and content of the year. And so it goes, we are thrilled to bring you 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue what we hope will be the next Masterpiece blockbuster series, about the epic life of Queen Victoria, Chicago, Illinois 60625 which will fill the Sunday night time slot that Downton Abbey held to Main Switchboard great success. Following Victoria from the time she becomes Queen (773) 583-5000 through her passionate courtship and marriage to Prince Albert, Member and Viewer Services the lavish premiere season of Victoria dramatizes the romance and (773) 509-1111 x 6 reign of the girl behind the famous monarch. Also, join us for new WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 seasons of Sherlock with Benedict Cumberbatch and Mercy Street, Chicago Production Center the homegrown drama series set during the Civil War. Leading up (773) 583-5000 to both of these season premieres, you can catch up with an all-day Websites marathon. wttw.com On January 16, we will debut an all-new channel and live stream wfmt.com offering for kids! You can find our new WTTW/PBS Kids 24/7 service President & CEO free on over-the-air channel 11-4, Comcast digital channel 368, and Daniel J. Schmidt RCN channel 39. Or watch the live stream on wttw.com, pbskids.org, and on the PBS KIDS Video COO & CFO Reese Marcusson App. -

37<F Aisid M . HZ-Li CADENTIAL SYNTAX and MODE in THE

37<f AiSId M. HZ-li CADENTIAL SYNTAX AND MODE IN THE SIXTEENTH-CENTURY MOTET: A THEORY OF COMPOSITIONAL PROCESS AND STRUCTURE FROM GALLUS DRESSLER'S PRAECEPTA MUSICAE POETICAE DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By David Russell Hamrick, B.A., M.M, Denton, Texas May, 1996 37<f AiSId M. HZ-li CADENTIAL SYNTAX AND MODE IN THE SIXTEENTH-CENTURY MOTET: A THEORY OF COMPOSITIONAL PROCESS AND STRUCTURE FROM GALLUS DRESSLER'S PRAECEPTA MUSICAE POETICAE DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By David Russell Hamrick, B.A., M.M, Denton, Texas May, 1996 Hamrick, David Russell, Cadential syntax and mode in the sixteenth-century motet: a theory of compositional process and structure from Gallus Dressier's Praecepta musicae poeticae. Doctor of Philosophy (Musicology), May, 1996, 282 pp., 101 tables, references, 127 titles. Though cadences have long been recognized as an aspect of modality, Gallus Dressier's treatise Praecepta musicae poeticae (1563) offers a new understanding of their relationship to mode and structure. Dressier's comments suggest that the cadences in the exordium and at articulations of the text are "principal" to the mode, shaping the tonal structure of the work. First, it is necessary to determine which cadences indicate which modes. A survey of sixteenth-century theorists uncovered a striking difference between Pietro Aron and his followers and many lesser-known theorists, including Dressier. -

Bach Festival the First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation

Bach Festival The First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 1921, 2013 THE 2013 BACH FESTIVAL IS MADE POSSIBLE BY: e Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil DEDICATION ELINORE LOUISE BARBER 1919-2013 e Eighty-rst Annual Bach Festival is respectfully dedicated to Elinore Barber, Director of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute from 1969-1998 and Editor of the journal BACH—both of which she helped to found. She served from 1969-1984 as Professor of Music History and Literature at what was then called Baldwin-Wallace College and as head of that department from 1980-1984. Before coming to Baldwin Wallace she was from 1944-1969 a Professor of Music at Hastings College, Coordinator of the Hastings College-wide Honors Program, and Curator of the Rinderspacher Rare Score and Instrument Collection located at that institution. Dr. Barber held a Ph.D. degree in Musicology from the University of Michigan. She also completed a Master’s degree at the Eastman School of Music and received a Bachelor’s degree with High Honors in Music and English Literature from Kansas Wesleyan University in 1941. In the fall of 1951 and again during the summer of 1954, she studied Bach’s works as a guest in the home of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Since 1978, her Schweitzer research brought Dr. Barber to the Schweitzer House archives (Gunsbach, France) many times. In 1953 the collection of Dr. Albert Riemenschneider was donated to the University by his wife, Selma. Sixteen years later, Dr. Warren Scharf, then director of the Conservatory, and Dr. -

Performing Michael Haydn's Requiem in C Minor, MH155

HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America Volume 9 Number 2 Fall 2019 Article 4 November 2019 Performing Michael Haydn's Requiem in C minor, MH155 Michael E. Ruhling Rochester Institute of Technology; Music Director, Ensemble Perihipsous Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal Recommended Citation Ruhling, Michael E. (2019) "Performing Michael Haydn's Requiem in C minor, MH155," HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 9 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol9/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Media and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America by an authorized editor of Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Ruhling, Michael E.. “Performing Michael Haydn’s Requiem in C minor, MH155.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 9.2 (Fall 2019), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2019. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Performing Michael Haydn’s Requiem in C minor, MH155 by Michael E. Ruhling Rochester Institute of Technology Music Director, Ensemble Perihipsous I. Introduction: Historical Background and Acknowledgements. Sigismund Graf Schrattenbach, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, died 16 December 1771, at the age of 73. Johann Michael Haydn, who had been in the service of the Prince-Archbishop since 1763, serving mainly as concertmaster, received the charge to write a Requiem Mass for the Prince-Archbishop’s funeral service. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 71, 1951

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEVENTY-FIRST SEASON 1951-1952 Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-first Season, 1951-1952) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, i4550ciate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Biirgin, Joseph de Pasquale Raymond AUard Concert -master Jean Cauhap6 Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Georges Fourel Theodore Brewster Gaston Elcus Eugen Lehner Rolland Tapley Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Norbert Lauga George Humphrey Boaz Piller George Zazofsky Jerome Lipson Louis Arti^res Paul Cherkassky Horns Harry Dubbs Robert Karol Reuben Green James Stagliano Vladimir Resnikoff Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici Bernard KadinofI Harold Meek Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Paul Keaney Harry Dickson Walter Macdonald V^IOLONCELLOS Erail Kornsand Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Carlos Pinfield Alfred Zighera Paul Fedorovsky Trumpets Minot Beale Jacobus Langendoen Mischa Nieland Roger Voisin Herman Silberman Marcel Lafosse Hippolyte Droeghmans Roger Schermanski Armando Ghitalla Karl Zeise Stanley Benson Gottfried Wilfinger Josef Zimbler Bernard Parronchi Trombones Enrico Fabrizio Raichman Clarence Knudson Jacob Leon Marjollet Lucien Hansotte Pierre Mayer John Coffey Manuel Zung Flutes Josef Orosz Samuel Diamond Georges Laurent Victor Manusevitch Pappoutsakis James Tuba James Nagy Phillip Kaplan Leon Gorodetzky Vinal Smith Raphael Del Sordo Piccolo Melvin Bryant George Madsen Harps Lloyd Stonestrect Bernard Zighera Saverio Messina Oboes Olivia Luetcke Sheldon Rotenbexg Ralph Gomberg -

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Theodore Kuchar, Conductor Alexei Grynyuk, Piano

Sunday, March 26, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Theodore Kuchar, conductor Alexei Grynyuk, piano PROGRAM Giuseppe VERDI (1813 –1901) Overture to La forza del destino Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891 –1953) Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 Andante – Allegro Tema con variazioni Allegro, ma non troppo INTERMISSION Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906 –1975) Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 Moderato – Allegro non troppo Allegretto Largo Allegro non troppo THE ORcHESTRA National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Volodymyr Sirenko, artistic director & chief conductor Theodore Kuchar, conductor laureate First Violins cellos Bassoons Markiyan Hudziy, leader Olena Ikaieva, principal Taras Osadchyi, principal Gennadiy Pavlov, sub-leader Liliia Demberg Oleksiy Yemelyanov Olena Pushkarska Sergii Vakulenko Roman Chornogor Svyatoslava Semchuk Tetiana Miastkovska Mykhaylo Zanko Bogdan Krysa Tamara Semeshko Anastasiya Filippochkina Mykola Dorosh Horns Roman Poltavets Ihor Yarmus Valentyn Marukhno, principal Oksana Kot Ievgen Skrypka Andriy Shkil Olena Poltavets Tetyana Dondakova Kostiantyn Sokol Valery Kuzik Kostiantyn Povod Anton Tkachenko Tetyana Pavlova Boris Rudniev Viktoriia Trach Basses Iuliia Shevchenko Svetlana Markiv Volodymyr Grechukh, principal Iurii Stopin Oleksandr Neshchadym Trumpets Viktor Andriiichenko Oleksandra Chaikina Viktor Davydenko, principal Oleksii Sechen Yuri і Kornilov Harps Grygorii Кozdoba Second Violins Nataliia Izmailova, principal Dmytro Kovalchuk Galyna Gornostai, principal Diana Korchynska Valentyna